Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

According to the fine book that accompanies this exhibition, The Great Wall was the brainchild of Kevin Fewster, Director of the Powerhouse Museum, who came up with the idea following a visit to China in 2002. After discovering that there had never been a travelling exhibition of the Great Wall, Dr Fewster and his colleagues at the National Museum of China got busy building one. The result is an odd collection of over 150 objects — most having little to do with the main subject of the exhibit — along with several videos, a few clever interactive visuals, and a stunning display of panoramic photography.

The structure of the exhibit follows the well-trodden chronological path of China's history, dividing that history into nine stages. It begins in ancient times prior to the Qin unification of 221 BCE with the building of the first territorial walls, and continues through the major dynastic periods of Han, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing (with a few minor dynasties such as the Northern Wei thrown in for good measure), moving the viewers into a kitschy impression of the contemporary era before they are ushered obligingly into the gift shop.

The Ming Dynasty Great Wall at Jinshanling, outside Beijing

photograph by Jean-Francois Lanzarone

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

Cramming 3000 miles (or 12,000 li, or 30,000 kilometres, depending on how one chooses to measure the collective length of the various structures that make up the Great Wall) and 2500 years of history into such a small space is a formidable task. This begs the inevitable question: why do it in the first place? Why not focus on the Ming Dynasty walls, which are after all the most recognisable and the most famous, not to mention the most enduring and ingeniously designed in the history of Chinese wall-building? Why not focus on the walls that are within driving distance of Beijing, to which countless millions of Chinese and foreign tourist hordes flock on an annual basis? Instead, we are treated to a broad panorama of Chinese history with little depth and even less contextualisation. For those unfamiliar with the broad expanse of Chinese history, the overall experience must be somewhat bewildering — not unlike being attacked by wave after wave of hairy barbarians, which were what the walls were meant to withstand in the first place.

If there is an overarching story in this exhibit, it can be summed up in two words: 'China's greatness'. This is after all the message that Secretary-General Pan Zhenzhou clearly meant to convey when he organised this exhibition with his 'barbarian' guest from the Powerhouse. This is the message that any international exhibition sponsored by the Chinese government is ultimately meant to express. Just look at all those clever tools and technologies the Chinese came up with to defend their territory and expand their empire over the sweeping centuries. In this exhibition, we see many weapons of war, from bows and arrows to projectile bombs and 'magical flying crows' that made use of China's invention of gunpowder in medieval times. We are even given the chance to fire a crossbow (using an imaginary digitised arrow) at a hairy barbarian (also digitised). This section reminds us that the crossbow was one of the most powerful tools for unifying the empire and founding the great Qin dynasty, forerunner to the centralised empires of the Han, Tang, Ming and Qing.

In another section we see how, during the thirteenth century, the Mongols were able to lay siege to China's walled cities by using Chinese engineers to build 'cloud ladders', trebuchets and other ancient Chinese siege machines. These were eventually used to conquer kingdoms as far away as Persia and Eastern Europe. We are also reminded that despite the greatest walls of all — namely, the kiln-fired brick and mortar walls with towers and crenulations built in the Ming Dynasty — the barbarians known as Manchus were still able to conquer the ailing Ming and establish their own empire known as the Qing. The message: walls don't always serve their intended purpose.

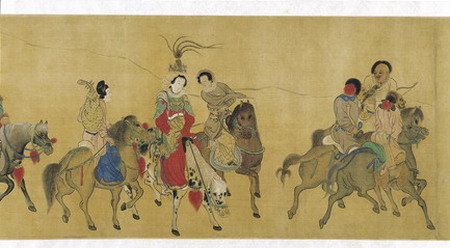

Other artefacts reveal how the system of walls built by various empires and dynasties in China's long history was just one of many strategies to quell steppeland raiders such as the Xiongnu and Mongols. Intermarriage was another, used until modern times to placate steppe chieftains by offering Chinese princesses as bait. As for how these women felt about becoming part of a barbarian's harem, little is said in this exhibit. One painted scroll, however, suggests that at least one such princess did eventually become attached to her mutton-chomping husband: when sent back to China for an imperial visit, she was reluctant to return to her ancestral land of sedentary rice-and-wheat-eaters.

Another strategy used since ancient times was to send military colonies out beyond the walls and then employ a policy of 'divide and conquer' by enfeoffing certain chieftains while keeping them quarrelling among themselves. Such methods sometimes backfired, since the barbarians quickly learned Chinese ways and were able to build powerful armies and centrally administered states of their own. The Manchus are one example. The eight-banner system used by the Manchus to conquer China was perhaps the most formidable fighting force in modern world history prior to the nineteenth century, and the Manchus built one of the most impressive land-based empires of the modern world.

While seasoned viewers of Chinese collections might ho and hum at the mediocre display of well-known artefacts trotted out in this exhibition to symbolise the various dynastic periods, there are a few diamonds in the rough. Among them is the Ming Dynasty scroll known as The Nine Commanderies. Attributed to Shen Yongmao and dated 1602, this scroll is a stunning visual map of the administrative divisions set up by the Ming to protect its northern borders. It includes carefully labelled diagrams of the roads, garrisons, forts, towers, passes and walls in an area spanning from the Yalu River (where China now shares a border with North Korea) to the famous Jiayuguan Pass in Gansu Province. (Only six commanderies appear in this scroll — the other three are missing.) Unfortunately, little information about this scroll is presented other than what I've remarked upon here, and only readers of Chinese will be able to decipher the text. Here and elsewhere, little effort is made to elucidate what these diagrams tell us about the building of the Great Wall and how contemporary scholars use them to assemble an overall picture of how the Ming walls were built and how they functioned.

Lured by the plaintive sounds of Mozart's Requiem, visitors will be drawn like moths into the panoramic display of Great Wall photographs, which takes up the entire length of one end of the exhibition hall. Taken by a team of specially commissioned photographers, these panoramic scenes require three data projectors simultaneously displaying separate views that together blend into a stunning composite image. As various tunes play in the background, we are treated to a visual spectacle of Great Wall scenes, from stunning mountain vistas to smiling Chinese stall-owners hawking kitschy Great Wall paraphernalia at major tourist sites. While much of the music fits the scenery, the Mozart seems oddly out of place.

photograph by Jean-Francois Lanzarone

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

Again, one must step back and ask, what are we learning from this panoramic display of Great Wallery? A voice-over describing the scenes — or at least the reactions of the photographers to them — might be helpful, as would labels telling us where and when the photos were taken. Otherwise, what we mainly learn here is that the Great Wall is great, that it is long, and that it is vast. But we knew that already.

Also missing are the changes in seasons that make the Great Wall so versatile as an aesthetic object. Where are the snow-covered mountains of winter, the multicoloured leaves of autumn, the budding plants of early spring? And because most of these images focus on reconstructed or well-preserved sections of the Great Wall (at least in the case of the Ming walls) we are treated to the illusory spectacle of a singular, strong wall receding along the ridgelines into the distance. This may perpetuate the myth of the Great Wall as a continuous structure rather than a strategic system of fortifications emplaced along certain passes and ridgelines.

In sum, by compressing the entire history of the Great Wall and in effect the history of imperial China into one exhibition, an unfortunate compromise is made between breadth and depth, with the former winning out at the expense of the latter. Ultimately, what comes out of this exhibition is a deep if somewhat hazy impression of the great will of China to keep the barbarians at bay.

Andrew Field is a lecturer in Chinese history at the University of New South Wales.

|

Institution: |

Powerhouse Museum in partnership with the National Museum of China in Beijing |

|

Curator/team: |

Claire Roberts (Powerhouse Museum), and other curators from Powerhouse Museum and various museums in China |

|

Design: |

Deuce Design |

|

Exhibition space: |

about 700 square metres |

|

Venue/dates: |

Powerhouse Museum, 28 September 2006 – 25 February 2007 |

|

Photography: |

Jean-Francois Lanzarone (Powerhouse Museum) |