Inside: Life in children's homes and institutions

‘Let no child walk this path again’: simple, strong words etched on a memorial plaque commemorating the girls, aged 13 to 18, who were incarcerated in the Hay Institution for Girls between 1961 and 1974 by the New South Wales Department of Child Welfare. This moral injunction is now etched on the hearts and minds of those who visited the Inside: Life in Children’s Homes and Institutions exhibition at the National Museum of Australia. To walk through that exhibition was like walking through the empty corridors and sparse dormitories of an abandoned institution. The cold black and white photographs of hopeful little faces lined up in rows, ready to enter various children’s homes around Australia, are a testament to the enormous duty of care we, as a society, placed on these institutions. A photograph of the teenage girls working in the Hay Institution garden exposes brutally how that ‘care’ was meted out behind the high walls and closed doors.

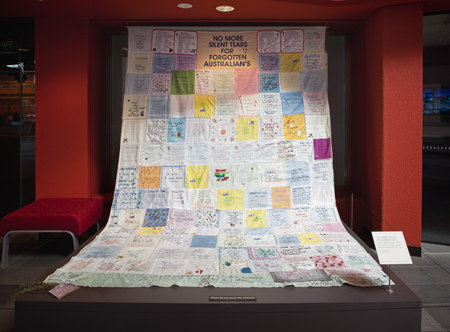

photograph by Jason McCarthy, National Museum of Australia

Wilma Robb was one of those girls sent from the Parramatta Girls Home to the Hay Institution, describing her ordeal in the blog set up to accompany the exhibition:

Girls were sent to Hay despite their having committed no crime and without a legal trial. Girls were not permitted to speak, without permission, or to establish eye contact with anyone. This rule was enforced despite the fact that the ‘silent system’ was outlawed in NSW in the late 1800s. Girls endured a regime of hard labour without school education.

Objects in the exhibition bear silent witness to the personal experiences of those who lived inside these institutions as children. A simple leather strap, the ‘Clontarf strap’, is revealed as hiding an inner band of steel: the cruel shock of steel encased in leather on soft flesh echoes round the room. William ‘Bill’ Brennan made the leather strap in the exhibition when he was aged in his 50s as a copy of the ones he made as a boy in the leather workshop of Clontarf Christian Brothers Home. Bill made the strap as a ‘witness’ to his experience in the Homes.

Many of the visitors to the exhibition stand before these mute testaments of cruelty to children and weep. Those who, like Bill, are aged 50 or older wonder how this could have been happening just down the road or in a town not far from where they grew up. Their memories are of a boisterous outdoor childhood in the sun, playing with other kids around the neighbourhood, summers at the beach and school camps. Australia was the ‘lucky country’, a land of wide horizons and boundless opportunity. In the post-Second World War euphoria, Australia boasted that its children were a new breed: taller, stronger and healthier than their parents. That was the ‘outside’ national marketing story, the story that brought many 10-pound poms to the land of sunshine and oranges.

During this outwardly buoyant period in our nation’s history from 1950 to 1980, more than half a million children were unseen and unheard ‘inside’ Australian welfare homes. Of the estimated 500,000 children in institutional care during this period approximately 50,000 were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, including many members of the Stolen Generations, and 7000 Former Child Migrants from Britain and Malta. The majority were non-Indigenous Australian children, identified in a 2004 Senate report as the ‘Forgotten Australians’. Children who were placed in care for many reasons, including being orphaned, family poverty or parents simply unable to cope in the days before single parent benefits or the childcare facilities available today. Children were criminalised because of circumstances in which they found themselves; charged with being uncontrollable, neglected or in moral danger – not because they had done anything wrong, but because family and society let them down.

The 2004 Senate inquiry led to the Australian Government formally apologising to the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants on 16 November 2009 and funding the National Museum of Australia to create a specific exhibition, Inside: Life in Children’s Homes and Institutions in 2011.

on loan from Leigh Westin

The exhibition provides a voice for those who had grown up inside these institutions. Visitors enter the space through a veil of tears: Leigh Westin’s patchwork of handkerchiefs, each inscribed with the names or words of inmates, a testament to bravery she calls No More Silent Tears for Forgotten Australians. The exhibition itself is a patchwork of memories, words and objects, giving voice to the silent. These lovingly kept scraps of personal history have been seamlessly stitched together by the invisible hand of the exhibition curators and designers. The curatorial team wanted to ensure that the design of Inside would capture the emotion of the experiences of forgotten Australian so they employed Tasmanian interdisciplinary Aboriginal artist, Julie Gough, who describes herself as a ‘sculptor of stories’:

I sculpt as my way to retrieve the forgotten or unspoken narratives of this nation, and to invite the viewer to engage with stories and implications perhaps not otherwise voluntarily approached.

One of the voices made the long sea journey between England and Australia, bringing emotions awash on the cold seas of distance and loss into the exhibition space. Former Child Migrant Rupert Hewison remembers, in a post to the Inside blog, his time at Saint Faith’s Home in Surrey, England, and his journey to the Fairbridge House, ‘Tresca’, in Tasmania:

On my first full day at Tresca I remember in the laundry where there was a copper for washing clothes, the usual stirring stick was broken in two. I asked how it had become broken and Brian said, in hushed tones, that Paul had caught a baby rabbit and kept it in a shoe box under his bed. ‘Dad’ had found out and hauled Paul out of bed at night time and hit him across his back with the stirring stick until blood came through his pyjamas and the stick broke.

The exhibition is housed in the small Studio Gallery at the National Museum. The space is modest and the placement of internal partitions creates the feeling of being enclosed in narrow corridors lined with small rooms: alcoves of misery, each with a sad story attached to a few objects like an empty iron cot, or a lonely misshapen toy koala, or a collage of photographs and a child’s towel; small objects evocative of huge loss, grief and unshed tears. The power of this exhibition is in the felt absence, the silence and stillness of objects redolent with suppressed screams. The tone, both visually and auditory, is sepia: brown and dull green pieces of material, faded old letters and photos, interspersed with phrases of memory. Absent are bright colours, sunshine and oranges.

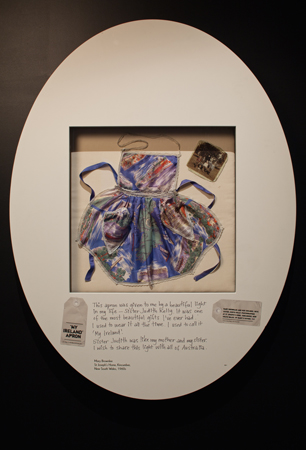

In this semi-gloom the objects created by acts of kindness shine out; one is a little girl’s apron. ‘My Ireland’ is the name that Mary Brownlee gave to the apron that was especially sewn for her by Sister Judith Kelly, at St Joseph’s Home in Kincumber, New South Wales.

on loan from Mary Brownlee

The exhibition is restrained and sparse, not a ‘blockbuster’ for the Museum, but it has been a dam buster for the Forgotten Australians, breaking through the institutional walls that for so long kept their stories hidden. Silence shrouded the lives of the children behind these walls and closed doors until the children themselves grew up and demanded to be heard. Care Leavers of Australia (CLAN) co-founder Joanna Penglase is one of those strong voices, and has written a powerful article on the CLAN website, entitled ‘Wardies and Homies: the Forgotten Generations’:

The older generation of ‘wardies’ and ‘Homies’ are the forgotten, and perhaps the hidden generations, We number hundreds of thousands across Australia, more than the Aboriginal Stolen generations, more than the adoptees who have services in every state, more than the child migrants who numbered at most ten thousand people. This is not to deny in any way the significance of those tragic histories or the right of those groups to recognition and to services.

But the story of white Australians children growing up in care has not been told, let alone acknowledged.

The Australian nation had to grow up itself before it could face its own dark childhood and hidden histories. Inside is a stimulus for national rethinking of who we have been, who we are and what we aspire to be. If a nation’s character is revealed by the way it treats children in its care, then Australia turned the face of a prison warder towards many of its children. Their voices are heard in the exhibition text and are dynamically engaged through the moderated interactive blog, accessible on the internet and through terminals in the exhibition space. The voices that echo through the tangible exhibition are recorded forever in the digital memory of this event on the National Museum’s website.

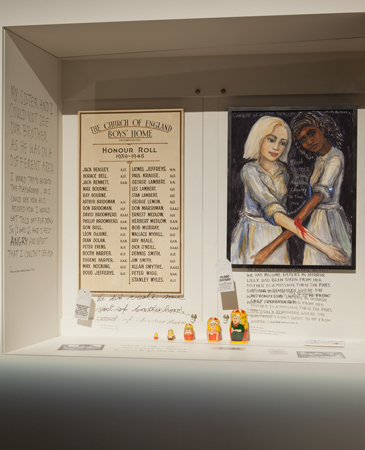

Blood Sisters by artist Rachael Romero leaves us all with an indelible memory of incarcerated children bonded through by suffering.

Let no child walk this path again.

National Museum of Australia

Diana James is a senior research associate in the Research School of Humanities and the Arts at the Australian National University, Canberra.

| Exhibition: | Inside: Life in Children's Homes and Institutions |

| Institution: | National Museum of Australia |

| Curators: | Jay Arthur (lead curator), Karolina Killian, Adele Chynoweth, Julie Gough (consultant curator) |

| Exhibition design: | Freeman Ryan Design |

| Graphic design: | Freeman Ryan Design |

| Floor area: | 200 square metres |

| Venue/dates: |

National Museum of Australia, Canberra Melbourne Museum |

| Exhibition website: | www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/inside_life_in_childrens_homes_and_institutions/inside |

| Exhibition blog: | www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/inside_life_in_childrens_homes_and_institutions/inside_blog |