« back

::

next »

The Biodiversity Gallery, South Australian Museum

by Rob Morrison

Those of a certain age watch their lives turn into history. They discover household objects from their infancy as curios in antique shops, while events from their childhood feature in newspaper columns headed 'The way we were'. Their customs and even their language may seem arcane to younger people around them. So it can be with museums.

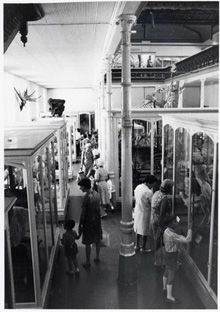

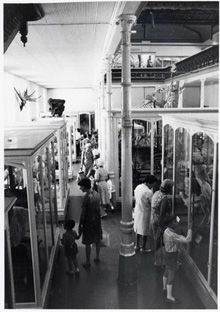

Being of a certain age I have seen the South Australian Museum's (SAM's) natural history displays morph at least three times. In my extreme youth it was a classical museum, its specimens arranged as in a colossal Victorian cabinet of curiosities. You entered a huge hall, where casts of gigantic fish were fixed to the walls beneath the ceiling. One, of a vast basking shark, was mighty enough to dominate the nightmares of the very young, despite that animal's non-threatening ways. Many museums of that period were dismissively described as being 'full of bones in glass cases'. Glass cases abounded; many with bones, it is true, but some with small dioramas of native species. As a child I marvelled at the taxidermist's ability to create scenes like that of a platypus in a pool, its surface a sheet of wrinkled glass that beautifully simulated wind on a pond. Larger displays featured subjects as diverse as Mawson's sled dogs, a family of thylacines, Egyptian statues and extinct bandicoots. There were many jars of specimens preserved in liquid, too, such as the stages of a kangaroo joey's development, and two dinosaur leg bones stood like sentries at the bottom of a staircase that led upward to more glass cases of curios from other worlds.

The old 'Cabinet of Curiosities' mammal gallery, South Australian Museum north wing

South Australian Museum Library

Museums then and later displayed their animals taxonomically. I say 'animals' deliberately for, despite their natural history tag, most natural history museums in Australia seemed only to include zoological and geological material, with plants virtually ignored. SAM was no exception. There were mammal galleries, reptile galleries and bird galleries, where dioramas large and small reproduced scenes of the Australian bush and its birdlife in exquisite and realistic detail.

For six years I presided over South Australia's two zoos, the dismantling of some of their old Victorian menagerie cages and the building of new exhibits. The sciences that dominated zoo exhibits long ago were taxonomy and anatomy, with animals grouped in zoological orders to display their various adaptations. The sciences dominating today's zoo exhibits are arguably genetics, ethology and ecology. Modern zoo exhibit design encourages natural behaviours and even an ecological focus that may see animals as diverse as tapirs, siamangs and otters sharing the same exhibit, which is dressed with regionally appropriate plants.

Some museums have also taken this route, their displays turning from anatomy and taxonomy to ecology. The South Australian Biodiversity Gallery opened in February 2010, and many new exhibits and some old favourites have been redeployed within it to show the diversity of South Australian wildlife and the links between the state's animal species.

The gallery's development

A case from the old bird gallery, dense with information

photograph by Michael Kluvanic

The South Australian Biodiversity Gallery was born from both strength and weakness. The impressive Indigenous Cultures gallery below it takes up a great deal of space. In a museum like SAM, which has no room to expand, such developments have a knock-on effect. The fish gallery was compromised and the bird gallery reduced. The skeleton gallery had already gone, the reptile gallery was closed, while the fossil gallery had been moved and the Australian mammal gallery shifted and condensed as a temporary exhibit that was little more than a store on view to the public. To top it off, extensive earthquake mitigation work required in much of the building had disrupted existing exhibits, and set the stage for considerable change.

According to David Kerr, the museum's Manager of Development and Design, the museum had a plan to redevelop the animal galleries, but lacked the resources and a strategy to develop the existing displays, which had become both tired and compromised. A new approach was needed.

The converted lift well with its giant squid and deep sea creatures

South Australian Museum Library

Planning for the new Biodiversity Gallery began in earnest in 2001. Modest funding from the National Heritage Trust allowed for a pilot project that was completed in 2003 and set the scene for the more ambitious gallery that would open seven years later. An old lift well, running from the bottom to the top floor of the museum, had been gutted and converted to a vertical display of marine life: its centrepiece a vast giant squid, Architeuthis dux, modelled on an 11-metre-long specimen from New Zealand. It now forms one end of the Biodiversity Gallery. Standing on the thick glass plate at the top and peering down, you look into a simulation of the ocean, its depth compressed to reveal animals from pelagic fish of the deep to benthic organisms on the sea floor. A window on each floor offers views of animals that live at various depths, and interactive screens interpret the exhibit, the whole united by the enormous squid suspended vertically in the middle of the display.

This exhibit, extremely popular with visitors, abandoned a traditional taxonomic focus and took ecology and habitat as its themes. These themes have also governed the planning of the Biodiversity Gallery. What crystallised in the process were integrated approaches to visitation, exhibit design, education and research.

The design of the gallery

A diorama in the old bird gallery showing pelicans in the Coorong

photograph by Michael Kluvanic

Faced with the challenge of serving many needs with limited space and resources, the design team elected to show a transect of South Australia, from its arid north through temperate woodlands to coastal habitats and, finally, the marine environment. This means that the displays now deal less with the classification and structure of animals and more with revealing how an ecosystem works.

The old, large bird dioramas had showed various bird species in context. That approach has been broadened to show numerous smaller dioramas with a wide range of animals that might be found in places such as a billabong, a rockpool, a woodland or desert dune, both by day and by night. Placing animals in context and telling stories have been important considerations in the exhibit designs.

A view in the Biodiversity Gallery, desert nightlife and waterhole

photograph by Grant Hancock

To some extent this approach mirrors what has happened in zoos. But Mark Hutchinson, curator of reptiles at SAM, sees some important differences between zoo and museum exhibits. In a zoo, he explains, visitors can be disappointed when an animal is in its shelter, asleep, hidden by plants or far away. Mounted museum specimens allow the visitor to see exactly what an animal is like at very close quarters and it is always there, its characteristics captured by a skilled preparator, optimally displayed along with other animals that share its real-life habitat.

This treatment reflects the design team's view that nothing adequately replaces real 3-dimensional objects, the curation and display of which remain major reasons for museums to exist. The early galleries were information-dense, and used by visitors to learn about animals. The design team reasoned that information about animals is now much more up-to-date and more readily available from field guides, natural history books and the internet. There was therefore little point in trying to provide detailed facts as part of the exhibition. They have tried instead to use interesting snippets to engender in students and casual visitors the kind of interest that will make them want to research topics from these other sources. They are pleased that the gallery seems to work well in this way, appealing to students from kindergarten to university. The gallery was also designed with tourists in mind. Through the Biodiversity Gallery, visitors to South Australia can acquire a preview of the state and its wildlife before leaving the city.

Information is certainly provided but, rather than offering extensive information on each display, the gallery features concept boxes at particular sites which explore important biological principles common to many species. Topics such as endoskeletons, larvae, animal defences, reproduction, feeding behaviours and extinction are dealt with in this way, the information layered so that a visitor who is browsing may note only one or two major points before passing on, while a more studious reader can find additional information. A 'concept box' on evolution, detailing 20 or so thinkers who played a part in revealing its mechanisms, is a welcome feature.

A concept box (right) dealing with how marine animals feed

photograph by Grant Hancock

The former limitations of the gallery have been turned into advantages. The low ceiling, which might have felt oppressive, is painted black throughout and consequently disappears in the low ambient light. That might sound sombre, but brilliant display lighting is directed onto the specimens and fills the gallery with colour and light. Because the exhibits inside the cases are brighter than their surroundings, reflections from the many glass surfaces are almost nonexistent. In places a false ceiling has been placed below the real one, pierced to allow lights above it to shine through, so that the floor of the woodland is dappled with leaf-filtered sunlight and the marine exhibit conjures up reflections from waves under a jetty. Unobtrusive sound effects of animals and nature enhance the experience.

The false ceiling in the temperate woodland throws dappled light on the floor

photograph by Ross Williams

The desire to escape from being perceived as static and boring has encouraged some museums to introduce digital displays for younger visitors reared in the computer age. Striking the correct balance between computerised screens and real objects can be tricky. Too much of the latter, and you might not escape the fusty label; too much of the former, and you could wonder why you need museum displays at all. The design team for the Biodiversity Gallery has struck an ideal balance. Information is there, but intimately linked to aspects of the exhibits themselves, not as an alternative to them. The screens, like the gallery, feature a black background against which coloured graphics and photographs achieve a heightened affect. Reducing informational content on these interactive screens has another purpose. As education officer Simon Langsford observes, the staff want the exhibits, not the screens, to be the features that visitors spend their time on, and a rapid turnover at the screens also ensures that more visitors can use them.

Information screens in the gallery enhance the displays

photograph by Grant Hancock

One of SAM's great strengths is its scientific research, and the gallery reflects this, frequently referencing the research activity that has informed its displays. In the skeleton exhibit, for example, is a specimen box of skull and bones just as it appears behind the scenes, showing the kind of packaging, labelling and field notes that are common to museums worldwide.

Museum heritage is also picked up in drawers, both vertical and horizontal, set into the display cases. These are pulled out to reveal an astonishing variety of collections. Pinned butterflies, skulls, worms and other bottled specimens, labelled and floating in their preservatives, are all there. In the museum of old these were part of the major displays, contributing to the perception of bones (and bottles) in dusty cases. Presented in drawers like this, often with their ancient, beautifully handwritten collectors' labels, they provide a valuable museum 'feel' without dominating the gallery. Some add another element that the designers wanted; surprise. The drawers are not identified, so you have to open them to discover what lies inside. It might be spiders or parasites, shells or animal droppings.

A drawer opened to show its contents

photograph by Grant Hancock

Other small surprises are everywhere. A hopping mouse greets small children at eye level as it rears its paws against the inside of the glass of its desert display. Small insects and frogs suddenly come into focus among the foliage of a woodland scene. A few exhibits are built specifically to provide that sense of intimate wonder. Children who duck below a marine display can emerge inside it with their heads in a perspex bubble that, much like a diver's helmet, brings them face to face with a wobbegong and octopus in the centre of the display itself.

Elsewhere in the skeleton display, in which examples of the various vertebrate classes are represented, a fabulous exhibit seems to have come straight from a Dr Who episode. Nicknamed the 'Chimera', it has been beautifully built from bones of fish, reptiles, birds and mammals to show what might lie inside a six-legged, winged, clawed, crested monster. Visitors are encouraged to identify where each bone belongs inside the real skeletons alongside; a kind of treasure hunt that leads a viewer from the passive process of simply seeing into the more active and analytical one of observing.

The skeleton case with the 'Chimera' in the last section

photograph by Ross Williams

The 1000 square metres of the gallery have been used to good effect. An old building, the museum has pillars at intervals that support the floors above. In the entrance to the gallery these have been turned into features that exploit their tall cylindrical form. One shows the world's animal species arranged in their taxonomic groups, another delineates the palaeontological timeline of their evolution. This specially designed introductory area has integrated audiovisual support, allowing it to be used for small public lectures, student workshops, launches and similar relevant activities. Nearby is a research area where visitors can use computers for information, a video on biodiversity provides an introduction to the gallery displays, and video screens introduce visitors to the diversity of South Australian environments.

The colonnade meeting place and entrance, with information columns and video screens

photograph by Ross Williams

The museum's early displays featured cases of pinned insects, but later exhibits had little in the way of invertebrates. As Jan Forrest, leader of the team that developed the content of the exhibition, stressed, 'Given that these animals represent about 95 per cent of the animal kingdom, it was quite an omission'. It meant that, in showing the biodiversity of South Australia, these specimens had to be prepared from scratch.

Within museums, soft-bodied specimens were traditionally displayed in liquid preservative inside bottles; squashed, distorted and colourless, perhaps the least aesthetically pleasing way of displaying anything. In the Biodiversity Gallery they are there, but freeze-dried or in the form of exquisitely prepared models. There are more than 12,000 of these, cast by the museum's taxidermist, Jo Bain, and his team of assistants in a variety of modern plastics and synthetic rubber from moulds prepared using real specimens.

A section of underwater jetty pylon, showing organisms in their natural colours

photograph by Grant Hancock

Skilful painting has given them their lifelike finish, but what visitors see is not always what they would see in real life. This shows most clearly in magnificent recreations of underwater sections of a jetty pylon and rock wall. Sponges, sea squirts and other forms of marine life are clustered on them from the surface to the sandy sea floor. As you descend in the real ocean, red light is filtered out first, and any light remaining in the depths is blue. Red organisms, whether fish, crabs or sea stars, absorb this blue light and appear black, one of their main defences. In the gallery display they have been given their real-life colours, a startling range of reds and yellows that are never seen in nature by a human observer, unless by a diver with a powerful light, in recently captured animals or in dead specimens washed up on the beach. Such displays remind visitors that our perception of the natural world is limited by what our human senses can process; a point reinforced by displays elsewhere, such as a scorpion glowing under ultraviolet light and the extended visual spectrum of an eagle.

A section of underwater rock wall, showing organisms in their natural colours

photograph by Jan Forrest

Invertebrates are an essential and welcome addition. But the plants are still missing, apart from their role in dioramas, where they are used to show the habitat of various animals, and a small display of plants that can be used to attract butterflies to a garden. Plants were considered for inclusion but, with only 18 months to develop the physical gallery, it was decided that including plant displays would be infeasible, and the designers had instead to concentrate on the museum's strengths. With all available space occupied it is also hard to see where plant exhibits would have fitted. That aspect will improve. The gallery was constructed during a severe drought; but, now that the rains have come and arid zone plants especially have regrown, the team expects to secure new plant specimens from each region. These will be used to dress the displays and will provide accurate examples of the habitats of small creatures such as insects, which will be mounted on them.

While the floor that houses the gallery is long and rectangular, exhibits are not arranged in linear fashion but as a series of islands around which interconnected paths wander, from the inland arid zone, through temperate woodland, into the coastal zone and finally to the sea, where the gigantic basking shark of my childhood, in context now, dominates a large display of marine animals of the Southern Ocean. Clear divisions between the habitats are blurred, as they are in nature, and visitors frequently backtrack, helping them to see the connections between the habitats and the animals that share them.

The marine case, with the basking shark in context

photograph by Gran Hancock

Although there are parallels between museum and zoo displays, in this digital age there are also growing parallels between museum exhibits and electronic media; not just in the way that interactive video screens now display information, but in how younger generations reared on television and video now perceive and interpret their world. Part of the power of television is its ability to compress or expand time, transport a viewer instantly to another time or place and present through mechanisms such as macro photography or time-lapse footage a different, unusual and often arresting aspect of something commonplace.

This approach is used to good effect in the gallery. The display on parasites borrows from macro photography, with huge model parasites, exact in every detail, clinging to the inside of the glass around their display. Grotesque slime trails on the inside of the glass add to the effect. Real macro photography comes into its own with videos of insects doing interesting things, while elsewhere video is used in a screen above immaculate models of the giant cuttlefish to show how they change their colours and patterns while courting. As you enter the gallery, the last thylacine paces in front of you in a black-and-white projection that is both an arresting introduction to a section of the gallery that deals with Australian extinctions and a poignant reminder that South Australia has the dubious honour of being called the mammalian extinction capital of the world.

Biodiversity education

School students are at home with these digital and video elements, but there is much more in the gallery especially for them. The museum hosts two education staff employed by the South Australian Education Department, who have developed resources for school visits. Audio programs on individual MP3 players guide students through the four habitats. On arrival students collect not the traditional photocopied worksheets, but colourful laminated cards and booklets that are designed to involve them actively in learning. Younger students can be seen stepping out the length of a shark, or imitating a kangaroo's gait while, as part of the museum's 'Tell me a story' program for very young children, storytellers in the gallery make use of a trolley of hands-on materials. Older students, each supplied with differing information, collaborate to research material from each other and the gallery displays, while an interactive whiteboard will allow students to bring their own contributions to the gallery or create them there and take them home. A team of primary science project officers is also developing a unit of work for teachers who bring their classes to visit the gallery.

As with most museums, SAM offers community awareness programs, and the new gallery allows a focus on biodiversity, with weekly guided tours of the gallery and special programs on biodiversity during periods such as school holidays, biodiversity month and National Science Week.

The gallery's future

It is possible to find among the displays some mammal and bird specimens that once graced the dioramas in the long-gone galleries of last century. Some are starting to show their age but, just as the Biodiversity Gallery reflects major changes in the way that museums display specimens, it also reflects the designers' views on how those specimens should now be collected. Jo Bain recalls with repugnance his early employment, when he was sent with a shotgun to a national park to collect birds to be mounted. The entire design team shares this distaste, and has elected to use old specimens rather than kill sometimes rare animals to make new mounts. In any case, it seems unnecessary. Jo Bain has a large freezer of dead animals that routinely come to him from zoos and wildlife parks and as road-kill. He has a timetable in which these will steadily be transformed into new mounts to replace the older specimens now on display.

Mark Hutchinson recognises that museums don't very often get the chance to prepare a gallery like this, and the team wanted to create something that would endure and remain effective for a long time. That said, the sense of the gallery being a work in progress is very evident; not from its appearance but from hearing the designers' plans. As well as refurbishments and the incorporation of new specimens in displays when they become available, there are adjustments already planned for the gallery. Simon Langsford has many additions in mind, especially to the contents of the pull-out drawers. Jo Bain wants to use what he regards as wasted space behind the facades of the exhibits. He plans small peepholes, at child height, where children can peer in and see small scenes, mini dioramas and animals as they appear by daylight, in night time scenes and illuminated with ultraviolet light.

All want to spark in a new generation of children the sense of wonder that they themselves experienced through museum displays of earlier times. You sense that this gallery, already opened to an appreciative public for several months, will grow for some time yet.

« back

::

next »