review by Nicholas Drayson

The first thing many people think of when they hear the name Rothschild is not museums but wealth, riches, great sacks of gold. The small bank started in Frankfurt by Mayer Amschel Bauer in the late eighteenth century (he changed his name to Rothschild after the 'red shield' that was the firm's logo) grew over the next hundred years to become the pre-eminent banking firm throughout Europe. His great-grandson Nathan Mayer Rothschild (known to family and friends as Natty) eventually took over the English branch of the firm to become one of the most influential men in Britain. He continued the family tradition of banking and philanthropy and in 1885 was created the first Baron Rothschild — so becoming the first Jew to sit in the House of Lords.

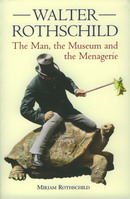

Natty had great hopes that his elder son Walter would follow in his footsteps but Walter was not cut out for banking. From childhood he had been fascinated by animals. He began collecting insects at an early age, then birds. He was interested in living animals — accompanying him to university at Cambridge in 1887 was a small flock of kiwis, and he had a life-long obsession with giant tortoises — but what he loved above all was taxonomy. For his 21st birthday his parents gave him just what he had always wanted: his very own museum, built in the grounds of the family home at Tring, just north of London. If they hoped this would assuage their son's ardour for dull taxonomy and help turn his thoughts towards the heady thrills of banking they were disappointed. Though Walter tried hard to fulfil his family obligations — he joined the firm for a while and became the local member of parliament — he spent more and more time with his collections. In 1894 he started publishing his own journal, Novitates Zoologicae, and his collectors scoured the globe for specimens. In 1915 he inherited the title Baron Rothschild from his father. Walter himself had no children, and the title passed on through his brother Charles's family. Charles was a much better banker than his brother but also fascinated by natural history — especially fleas. He in turn passed on his interest to his daughter Miriam who became one of the most famous entomologists in England. It is she who decided to write a book about her Uncle Walter (Miriam died in 2005 — this book is a reissue of one originally published in 1983).

Though hampered by a surprising dearth of existing records, Miriam Rothschild has amassed an impressive collection of facts. Not only do we have a thorough account of Walter's childhood and the development of the museum, we meet many of his associates, professional and personal. Though he never married nor had children, during his adult life Walter had at least two mistresses. He had a more murky association with a peeress of the realm who for many years blackmailed him. Although Miriam Rothschild claims to know the identity of the blackmailer, she does not reveal it, nor exactly what were the grounds of the blackmail. She hints that it was something sexual, and that Walter kept paying up for fear the truth would be revealed to his mother.

Walter's relationship with his mother was odd — he was always quiet in her company and lived with her until her death. But then Walter was odd. He found it difficult to speak, apparently managing only complete silence or loud bellowing. Though shy and gauche in company, he had a truly phenomenal memory. He knew the identity and location of each and every specimen in the museum. Though he found banking impossible and life outside the museum trying, he managed to fulfil his expected duties as a member of the Rothschild clan. As well as being the local MP for many years he was on the boards of various scientific bodies. As second Baron Rothschild he became de facto head of British Jewry, and it was to him that the 'Balfour Declaration' outlining British government support for a Jewish nation in Palestine, was addressed.

The affectionate portrait that Miriam Rothschild paints of her eccentric uncle is one of the strengths of the book. From her own memories and those of family and friends we discover a man who overcame considerable personal challenges to become one of the greatest collectors and benefactors in modern zoology. The advantages of her 'personal' touch are to some extent counterbalanced by a distinct lack of critical assessment of the man and his work. She pays too little attention to discussing the value of Walter's idiosyncratic approach to collecting and describing, and I would have liked a little less one-sided analysis of his relationship with other museums and institutions. But as an account of the man and his museum I found the book engrossing. Though reprinted as a paperback it is well illustrated and well produced, with an unusually comprehensive index.

When in 1938, towards the end of his life, Walter donated the museum and its collections to the nation, it contained over two million insects, 300,000 bird skins, 200,000 eggs and a library of 30,000 scientific books. A legacy more valuable than gold.

Nicholas Drayson is a novelist and nature writer.