A characteristic of all museums, whatever their size, is the multiplicity of roles that they assume for themselves or that others call upon them to perform. A museum is likely to be a repository of artefacts and specimens, a visitor attraction, an educational resource, a centre of knowledge, a corporate hospitality venue, the guardian of an iconic or historic building, a source of identity and pride for its locality, a place of research, and the organiser of performances. It may have a number of branches, a series of departments and a range of specialisms in its staff and volunteers. A large museum will have a wide range of staff with many different skills and disciplines. The Manual of Museum Management provides 61 descriptions of the kind of jobs that are likely to be found in a museum of some size.[1] Needless to say, many museums combine these functions in just a few people, but the large list demonstrates the range of competencies that a modern museum requires. In the words of Stephen Weil, 'Nobody familiar with a museum can be other than dazzled by the extraordinary range of activities in which it regularly engages'.[2] The capacity of museums to adapt their mission to the changing needs of the communities they serve is an undoubted strength that in part accounts for their longevity as cultural institutions. However, it can also be a weakness, as specialisms develop that can fracture the organisation into a series of competing entities. At its worst a museum can become enmeshed in departmental enmities, with energy consumed by wasteful rivalry rather than in creative work to benefit the public. Even when matters have not deteriorated to that extent, a highly departmentalised structure can result in deadening bureaucracy and an inability to take advantage of collaboration across the organisation.

Roy Strong in his published diaries observed, on commencing his role as director of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1974, 'Departments enjoyed their insularity ... The rivalries between them could take on horrendous dimensions as they struggled for space, money and staff'. And also, 'Golly, how I know about compartmentalised museums ... They move in their own little worlds, totally uninterested in anything except their own wretched things and little thought for the public'.[3]

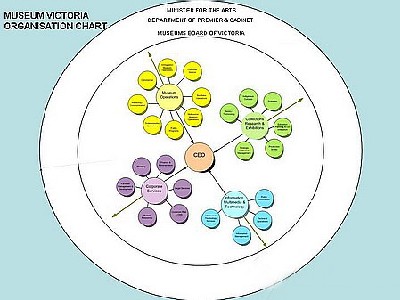

In 2002 Museum Victoria, which comprises Melbourne Museum, Scienceworks, the Immigration Museum and the Royal Exhibition Building, found itself in a crisis characterised by a $6 million projected deficit and a decline in visitor numbers at the new Melbourne Museum. The organisational structure had emerged from the needs of the construction and fit-out of the new building rather than from the operations of a museum with multiple venues and responsibilities. There was a clear and urgent need to bring coherence to the organisation. When I arrived to take up the post of chief executive officer (CEO) in August 2002 my colleagues had started to prepare the ground, with the beginning of work on a new strategic plan and also a valuable environmental scan. The existing plan was over-complicated and even features (albeit anonymously, thankfully) in Don Watson's book Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language as an example of 'windy summaries of ambitions'. Watson says, 'The result looks less like analysis than blarney, or a charmless parody of Soviet bureaucracy'.[4] The decision that I endorsed — to involve all staff in the preparation of the strategic plan — was greeted with a degree of cynicism, but gradually the workshops produced a more positive atmosphere as it became clear that the views of staff really did matter. An encouraging aspect was the degree of convergence about what was wrong with the museum and what could be done to correct it. Even more positive was the emerging belief that, if we got it right, the museum had a very exciting future. Exploring Victoria; Discovering the World is the title of the strategic plan and emphasises the museum's commitment to its locality and communities, research, discovery and a global perspective.

Before we got to that stage, however, the deficit — and the impending threat that we might not get to the end of the financial year with sufficient funds to pay staff salaries — had to be faced. I decided that it was necessary to reduce the size of the executive management team from nine people to five. It was a fairly unusual decision to make cuts at the top of the organisation rather than at the base; painful to implement, but essential as the first step in remodelling the organisation.

The next stage in the process was the initiation of a series of reviews of the museum's functions to examine what was current practice and to make recommendations for improvement. The reviews were carried out quickly over a period of six weeks by teams from within the staff, made up of providers of services and their internal clients, with a facilitator made available if required. Each team, having completed their review, then reported to the executive management team which considered every recommendation. Two hundred and five out of a total of 245 were accepted, with another 37 requiring further analysis. Only three were rejected at that point.

The final stage in the process was the realignment of the organisation into a single museum, with functions redefined to produce the outcomes identified in the strategic plan. In some areas this process involved implementing the recommendations of individual reviews virtually as they stood. In other areas long and detailed negotiations were necessary, involving the Staff Consultative Committee and the Community and Public Services Union as well as members of departments. The objective was straightforward: to create a single museum organisation capable of realising its full potential. It was also vital to define the special characteristics of each Museum Victoria site and to build on their strengths. In a parallel exercise, extensive research among visitors and non-visitors identified the needs of four different motivational groups. That enabled us to describe, develop and market the essence of each museum.

The entire process has taken two years, but improvements were introduced progressively over that period rather than waiting for a massive upheaval once every aspect of the realignment had been determined. At times some members of staff have felt frustrated at what has been perceived to be a long process. 'Why don't you just get on with it rather than waste time consulting staff?' was a remark at one staff meeting that I addressed at an early stage. There was a perception by some that the whole exercise was aimed at cutting staff numbers, hence the impatience to hear the worst — and quickly. The commitment to avoid further redundancies underpinned the eventual acceptance of the realignment.

A key decision was to create a leadership team made up of 26 senior managers from across the organisation and the five members of the executive management team. The leadership team has been essential in defining the projects that would carry forward the objectives of the strategic plan. These were further refined at a two-day board workshop, and the resulting corporate plan sets out an ambitious program of activity and development spread over five years. The plan is rolled forward on an annual basis; as projects are completed new ones are added to the list. In this way Museum Victoria has a clear vision of what it intends to achieve, how, when, for whom and for how much. That is essential for planning purposes and also for communicating with stakeholders such as the Victorian Government.

The corporate plan is supported by other plans relating to areas such as research and collections, information technology, marketing, commercial activities and public programs. Major breakthroughs have been the establishment of an exhibition framework and a staff training and development plan. I mentioned earlier that one of our objectives has been to reduce bureaucracy and encourage cross-departmental collaboration, yet this cascade of plans might suggest just the opposite. In fact, it is a prerequisite for both the release of creative talent in the organisation and the ability to change in an evolutionary manner.[5] Unless there is a shared vision and clear perspectives of the roles of individuals and groups in achieving the outcomes that will take the museum forward, time and energy will constantly be wasted on 'border disputes' and confusion. An integrated exhibition framework, for example, allows bottlenecks in production capacity, research capability and object conservation to be anticipated and addressed, clashing opening dates to be avoided, and the potential for public programs and marketing to be recognised at an early stage. The selections of gallery developments and temporary and touring exhibitions are made by an exhibition planning group that operates across the whole organisation. Project teams are established with a small core membership and a larger cluster of interested parties. These teams make recommendations to the executive management team for endorsement and then implement the decisions.

The result has been the release of creative potential that has seen, over the past three years, award-winning projects such as the Virtual Room, Marine Life: Exploring our Seas and Bugs Alive at the Melbourne Museum; House Secrets, Sportsworks, the Lightning Room and the Indigenous planetarium show at Scienceworks; and Getting In and Station Pier at the Immigration Museum, as well as museum-wide projects associated with our 150th anniversary, public programs, publications, educational resources and websites.

where independent people and groups act as independent nodes, link across boundaries, to work together for a common purpose; it has multiple leaders, lots of voluntary links and interacting levels.[6]

The differences between a hierarchy, a matrix and a network as a pattern of operation for an organisation can be expressed diagrammatically (see figure 5 above or From hierarchical to networked organisations for an enlarged image).

The essential steps towards creating a networked museum are these:

- a clear set of goals

- accepted organisational principles

- a commitment to devolve responsibility

- training and development to enhance the skills of staff

- mechanisms to break down boundaries between departments

- a strong emphasis on teamwork.

In Museum Victoria's quest to develop a networked museum, these have been essential steps:

- development of the strategic plan with full participation by staff

- agreement of organisational principles by staff

- incorporation of the five key strategic directions in all job statements

- centralised recruitment for staff

- a new induction program for all new staff

- leadership training for managers

- enhanced skills training

- abolition of those committees that were judged to be unproductive

- establishment of cross-departmental teams with clear terms of reference and specified outcomes

- flexibility within the customer service teams, which work across the three museums

- launch of a new intranet to enhance communication.

2 Stephen E Weil, 'A success/failure matrix for museums', Museum News, American Association of Museums, January/February 2005, p. 38.

3 Roy Strong, The Roy Strong Diaries: 1967–1987, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1997, pp. 136, 142.

4 Don Watson, Death Sentence: The Decay of Public Language, Random House Australia, Milsons Point, 2003, p. 32.

5 J Patrick Greene, 'Creating a culture of change in museums', Museum 2000 Confirmation or Challenge?, Stockholm, 2002, p. 187-90.

6 Jessica Lipnack and Jeff Stamps, The Team Net Factor: Bringing the Power of Boundary-Crossing into the Heart of Your Business, John Wiley & Sons, 1993, quoted in David Skyrme, The Networked Organization, David Skyrme and Associates, http://dev.skyrme.com/insights/1netorg.htm, accessed 11 April 2006.