Important to me

A number of recent research projects have explored the benefits of taking museum objects to patients in hospitals and residential care centres.[1] There have also been workshops to evaluate wellbeing outcomes from programs that draw on aspects of heritage, especially in the United Kingdom, where they are termed ‘heritage-in-health’ programs.[2] In Australia several museums and galleries have developed programs for visitors with Alzheimer’s Disease or dementia. ‘Memories of childhood’ at Museum Victoria has been developed specifically for these visitors. The Tasmanian Museum and Gallery has a ‘gentle program’ that explores memories and objects for people with dementia and their carers.[3] In Canberra, the National Museum of Australia and the National Gallery of Australia also run programs tailored to visitors with special needs.

Drawing inspiration from such programs, I invited residents of Carey Gardens, an aged care centre in Canberra, to choose a significant object from among their possessions and participate in its documentation. I recorded their personal history of their object and undertook research into each. While the project was primarily concerned with documentation, the objects were also presented as an exhibition at the centre, Important to Me, held in May 2013. The project demonstrated successful community engagement and promoted the development of interaction between health and museum spheres. Carey Gardens has subsequently instigated a monthly ‘show and tell’ session that encourages residents to talk about significant objects and events in their past lives that would otherwise remain hidden from view. A repeat project with different participants is planned and similar ventures in other centres are being developed. This paper offers an overview of the project and its evident benefits for health and wellbeing.[4]

Background

My visits through the years to friends and family in aged care centres in Australia and overseas have often been mixed experiences. In some places, residents spend much of their time just sitting, often (but not always) in company; together, but alone. I was keen to develop a project that would bring people together with something tangible to discuss and compare, perhaps to find common ground. For those who were sufficiently robust, there was also a planned visit to a museum exhibition, facilitated by the museum’s access officer. Projects like the 2008 ‘Heritage in hospitals’ program developed by University College London and University College London Hospitals Arts, claim benefits to the health and wellbeing of patients who interact for a short time with museum objects. But is it the interaction or just the extra attention that is the boon?

My proposal was to document the history and significance of the objects chosen as a permanent record for the owners and their families. The accompanying exhibition was open to the community at the centre, their families and friends. It was also a museological project that I hoped would interest my colleagues. As a former National Museum of Australia curator, I was experienced in documenting the history of objects, their significance, provenance and associations. But it is just as important to record personal histories. Many families have objects with stories that are kept alive down the generations, but stories are also easily lost: Who was awarded the medals? Who made the quilt? When and why was Aunt Gwen given the silver bowl? You may think you will never forget the faces in the photographs but unless you write down their names, one day no one will have a clue. The documentation was important and the exhibition of the objects, stories and research would be a highlight and a celebration.

I had the ‘who’ and the ‘what’ but how to choose the ‘where’? I turned to local knowledge: I have been a member of a quilting group for many years and I asked my friends, some of whom had family members or friends in residential care in town, for recommendations. Which centre would likely take a punt on such a project? After much discussion, a list was drawn up and I contacted the first three. I had an enthusiastic response from Carey Gardens centre and its diversional therapist, Julie Grant.[5] Carey Gardens became the location for this pilot project. Located in the Canberra suburb of Red Hill, the centre is administered by Baptist Community Services, one of the largest providers of residential and in-home aged care in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Carey Gardens was opened in 1990 and provides 65 beds with ‘low care services’ with ‘ageing in place’.[6]

After talking to the staff at Carey Gardens I wrote to residents, while Julie Grant assisted by talking about the project with potential participants. The value of such facilitation by staff at the centre cannot be underestimated. Notwithstanding numerous other demands on their time, all staff involved were always welcoming and helpful. The project had to be accommodated within a busy schedule of activities and excursions, including medical appointments, religious meetings, computer sessions, quizzes and concerts, as well as visits by friends and family. For this project, flexibility was the key, as those residents listed for interview were not always available on the designated day. The final list of participants did change for various reasons, such as residents not feeling comfortable they remembered enough (or perhaps not wanting to remember), privacy issues or unforeseen circumstances.

My invitation specified three requirements:

- an object that belongs to you

- a willingness to talk about your object and what it means to you

- where available, a photograph of you taken at the time the object was acquired.

Fifteen residents responded to my invitation and eventually I spoke to 12 about an object of their choice. And it was indeed their choice, not influenced by my inner curator (though this was, in one or two cases, slightly hard to adhere to). One person who professed ‘not to have much left’ still had several objects that yielded great stories. The owners’ recollections and the subsequent curatorial documentation and research formed the basis of the exhibition. The objects were many and varied and had originally accompanied their owners to the centre because they were special, holding significance and memories of times past for their owners. These were objects that had survived the whittling of belongings that invariably precedes such a move. Once embarked on the project and reassured that their objects would be of interest to others and worthy to be in an exhibition, the participants were happy to share their stories and recollections. Some had issues with hearing or memory loss, but gradually the stories emerged. In some cases it was possible to make links from the individual personal object to collections of national significance.

The objects

The twins

In 1955, Colin took up the position of supervising engineer for the Australian Broadcasting Commission (now Corporation) (ABC).

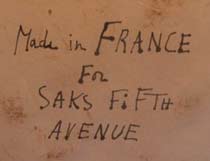

Though my wife was pregnant, I was immediately sent overseas to visit the British Broadcasting Corporation and our suppliers in England, Europe and America to purchase equipment to broadcast the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. Near the end of my trip I received a message: Joan is well – twins on the way! Walking back to my hotel along Fifth Avenue, I spied a statue of twins in Saks window. It seemed somehow symbolic and I couldn’t resist it.[8]

Some of the original equipment ordered by Colin remains inside the ABC-TV outside broadcast van that now forms part of the collection of the National Museum of Australia.[9]

National Museum of Australia

1934 MacRobertson Air Race

Eileen was a professional. Certificates and two Citizen of the Year awards attest to a significant and successful career of 50 years in nursing, from 1941 to 1991. ‘Nursing was a most fulfilling life together with community work, pastoral work, singing and family. I was a happy woman.’

Eileen also loved dancing, and she chose for this project a photograph of herself in Dutch costume, taken at an official concert in Albury in the 1930s.

The reason for the choice of costume also reveals a fascinating moment in Australian history. The Dutch entrant in the 1934 MacRobertson Mildenhall (London) to Melbourne Air Race, the Douglas DC2 plane Uiver, flew off course in a storm. A call was made over the wireless for listeners to drive their cars to the racetrack and line up to light a runway. The Uiver landed safely. The Albury Council website continues the story: ‘But the drama was not over. Daybreak saw 8 tonnes of DC2 bogged in thick Albury mud.’[10] The next day the plane was dragged out of the mud and continued to Melbourne to win the handicap division of the race, with an air time of 81 hours and 10 minutes. Some time later, a Dutch delegation visited Albury to thank the residents, and attended the concert where Eileen’s photograph was taken. The National Trust has nominated the DC-2 Uiver Memorial and its associated historic collection at Albury for listing on the State Heritage Register. With regard to the air race, which was held as part of Melbourne’s centenary celebrations, there are maps, posters and photographs of the planes, the pilots, sponsors and trophies in collections at the National Library of Australia, State Library of New South Wales and Museum Victoria.[11]

Tapestry by Dame Pattie Menzies

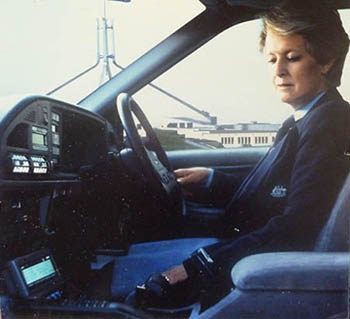

Robyn was the first female Commonwealth car driver in Canberra. She joined in 1984, and was in the fleet for 11 years.There was a lot of driver training on the skid pad and anti-terrorist training. When we practised manoeuvres around the track, the men would always say ‘ladies first’ and they would all sit and watch. Some of the old drivers were a bit wary and would even watch me change a tyre. When driving the Prime Minister there was always a police escort.

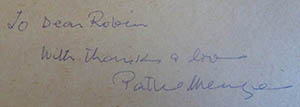

The tapestry of two Gouldian finches (Erythrura gouldiae), also known as rainbow finches, was a gift embroidered for Robyn by Dame Pattie Menzies GBE (1899–1995), who often requested Robyn as her driver in Canberra. The tapestry is inscribed on the back: ‘To dear Robin/With thanks and love/Pattie Menzies’.

In 1954, Pattie Menzies was appointed Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire. Her husband, Robert, prime minister of Australia from 1939 to 1941 and 1949 to 1966, was knighted in 1963, but she was always popularly known as Dame Pattie Menzies, not Lady Menzies. A collection of objects relating to Dame Patti Menzies held by the National Museum of Australia includes hats, dresses and gloves that she wore, as well as a handmade pillowcase and her Singer sewing machine.[12]

The debutante

A beautiful photograph of a debutante dates from Melbourne’s dark days in 1942. Darwin had been bombed and Melbourne residents were anxious. Nevertheless, they tried to maintain the rituals of everyday life. Gordon’s wife, Mavis, was photographed by Melbourne photographer Athol Shmith at her debutante ball at St Kilda Town Hall. During the Second World War fabric and clothing were rationed and accessories difficult to acquire. Mavis, who was just 18, put together a glamorous outfit by borrowing from several members of her extended family.

photograph by Athol Shmith

Gordon was in the army during the war. He spent time in Darwin and New Guinea before being posted to the Allied Land Forces Forward Echelon, the battle room at General Thomas Blamey’s headquarters. After the war Gordon returned to Melbourne, only to find employment on an oil rig in New Guinea. He later joined the Department of Navy at St Kilda. He met Mavis in St Kilda and they were married there in 1948.

Louis Athol Shmith (1914–1990), always known as Athol, was already taking photographs in his early teens. His first job was as a portrait photographer in Fitzroy Street, St Kilda. At age 19, he was already the vice-regal photographer, a member of the Royal Photographic Society in London and the winner of international competitions. In 1938, he opened a studio at 125 Collins Street. He was a popular artist and his projects included cigarette and car advertisements as well as photographing fashion, weddings and debutante balls. In 1948 he photographed Sir Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, who were in Australia with the Old Vic Theatre Company. Athol Shmith’s photographs are in the collections of the country’s major cultural institutions, including the National Gallery of Australia, National Library of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria.

The reverend

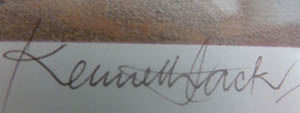

A significant object for Audrey is a painting by prominent Australian landscape artist Kenneth Jack (1924–2006) of the Smith of Dunesk Mission at Beltana, South Australia, where her grandfather, the Reverend William Gray spent four years in the 1920s, in a parish that spanned more than 100,000 square kilometres.

In his book Days and Nights in the Bush Gray recounts his work with John Flynn, Presbyterian minister and founder of the Australian Inland Mission and the Royal Flying Doctor Service, and the ingenuity of Alfred Treager, inventor of the pedal radio that revolutionised communications in isolated and remote areas of the country. Gray wrote that ‘many a patrol padre or border sister spent hours trudging miles for help’.[13] His black cat, Peter, often travelled with him in his car. Reverend Gray was photographed with his car at Italowie Gorge, on the other side of the Flinders Ranges from Beltana. The isolated gorge looks little different today.

William Gray’s trunk arrived in Canberra in 1939. Audrey was fascinated by his diaries detailing his life as a missionary, his manuscripts, and his photographs of the New Hebrides. Forty years later she began the daunting task of researching his life and cataloguing his papers, a project she completed in 1993.[14] Jack’s artworks have been collected by major Australian and international art galleries and an archive of Gray’s papers is held at the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University.

The exhibition

Institutionalisation, memory loss, deafness and fading eyesight are a few of the challenges faced by residents. However, even when some said ‘I can’t remember’, just talking about the objects, teasing out the provenance and associations, elicited responses that were less and less monosyllabic. ‘I haven’t thought about that for years’. The stories were gradually pieced together.I made a decision that I would not record an oral history in the first round, but take comprehensive notes. This method proved effective and with additional research, labels for the exhibition were produced including the history and the memories. The conjured reminiscences, some poignant, some amusing, were fascinating on many levels. The labels were much longer than approved for exhibitions I have worked on in cultural institutions). But that was appropriate to the audience: a small number of genuinely interested people. Visitors to the exhibition read all the labels in detail. Each participant had been sent the text for approval – and some even wished to add more words. All participants were given a copy of their label with a photograph of the object and the research. The centre also retains a folder with copies of all the labels and photographs.

An exhibition space is not a usual part of an aged care centre, though there are small meeting areas that can be adapted to this purpose. We chose a seating area with good light but also a bench, a sink and other kitchen elements. The transformation to display area was effected with a board over the sink and generous use of red hessian – a good foil for the objects and the framed labels, which were set in a bold, 14-point, black font on white paper. The participants found the layout of the labels clear and legible.

Conclusion

In most institutions there is much to keep residents occupied but it is usually ‘in the moment’. A song is sung and then another. There is no time for reflection on the where, when or why it is known to the singer. This project harked back to an earlier time. A time witnessed by the object and reflected back and brought to the fore again. This was a worthwhile project on a number of levels, personal and collective. From a curatorial point of view the documentation of family history and of objects that link to collections of national significance is very exciting. The attention residents received was beneficial but the interest generated by the project long outlasted this initial contact. Curatorial projects in other centres are being developed and there are plans for a repeat project at Carey Gardens with different participants. This model costs very little and can be used in residential care centres large and small, in any state or territory. A larger community project could be developed, bringing together objects from exhibitions in different centres to one exhibition area in a museum or gallery.One of the aims of this project was to connect people to their pasts. But it was also to alert staff to those pasts, lives full of incidents and events. In a care institution it is impossible not to become ‘institutionalised’ – it is the very nature of the place. There must be a focus on residents’ health, medicines must be given on time, and other routines carefully followed. Outings are organised and still there is often a focus on the collective. Large families would circulate the stories of the individual. But nowadays families may live interstate or further and visit rarely, the family circle is smaller but less intimate. There are few avenues for staff to get to know the details of individual lives. A photograph on a shelf in a room gives little indication of the layers of meaning and memories attached. By concentrating even on one object, much can be documented (and learned) about the owner.

As one of the participants in the projects remarked to me, ‘This was a good project; it gave us something to think about’.

My sincere thanks go to Ellie McFadyen, Suzie Higgie, Vikki McDonough and Mike Pickering, and the participating residents and staff of Carey Gardens.

Endnotes

1 In 2008, researchers and curators from University College London (UCL) and University College London Hospitals (UCLH) Arts developed a unique program, ‘Heritage in hospitals’, funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC award number AHG000506/1).

2 In 2011, researchers and curators from University College London (UCL), Newcastle University and Renaissance North West held a series of AHRC-funded workshops considering evidence for and evaluation of wellbeing outcomes, drawing on heritage, museums and museum objects. Researchers from these institutions have published a series of publications, including books, practice guides, exhibitions brochures, journal articles and book chapters. See www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/research/touch/publications, esp. EE Ander, LJ Thomson,G Noble, U Menon, A Lanceley, & HJ Chatterjee, Heritage in Health: A Guide to Using Museum Collections in Hospitals and Other Healthcare Settings, UCL, London, 2012.

3 http://www.tmag.tas.gov.au/learning_and_discovery/programs/community.

4 There are no doubt many such projects in different areas in Australia. I would love to hear of any in your region.

5 ‘Diversional therapy practitioners work with people of all ages and abilities to design and facilitate leisure and recreation programs. Activities are designed to support, challenge and enhance the psychological, spiritual, social, emotional and physical well being of individuals. The diversional therapist provides opportunities where individuals may choose to participate in leisure and recreation activities which promote self esteem and personal fulfillment’: www.diversionaltherapy.org.au/.

6 According to the BCS website, ‘low-level care places are for people who need some help. Mostly, people in low-level care can walk or move about on their own. Low-level care focuses on personal care services … accommodation, support services (cleaning, laundry and meals) and some allied health services …Nursing care can be given when required’. ‘Ageing in place’ refers to ‘aged care centres that offer both high-care and low-care, and to situations where it is possible to stay in the same centre if your care needs increase’: www.bcs.org.au/AgeCare/ResidentialCare.aspx.

7 I chose the objects for this paper based on their inherent historical interest, and they have been included here with the permission of their owners.

8 All residents’ quotes in this section are taken from the interviews conducted as part of the documentation project.

9 www.nma.gov.au/collections-search/display?irn=10202&app=tlf.

10 www.alburycity.nsw.gov.au/community-services/albury-airport/the-uiver-story.

11 For example, collection items related to the air race are described at: http://museumvictoria.com.au/collections/items/146675/medal-macrobertson-international-air-race-netherlands-1934 and http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/discover_collections/history_nation/aviation/crossing_oceans/air/macrobertson.html among others.

12 The Dame Pattie Menzies collection no. 2 is described at www.nma.gov.au/collections-search/results?search=adv&ref=coll&collname=Dame+Pattie+Menzies+collection+no.+2#ce=Collection%20name.

13 William Gray, Days and Nights in the Bush, Robert Dey Son & Co., Sydney, 1935.

14 http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/pambu/reels/manuscripts/PMB1123.PDF.