From the time my sister and I were quite young, we knew that our ‘Aunty Puss’ was once an army nurse. We knew about nurses because our mother was one: they looked after sick people, wore uniforms, walked very quickly, and had lots of friends who were nurses too.

The life of army nurses was more mysterious, formed of snatches of conversation we overheard. They had ‘been away together’ – to England, the Middle East and Papua New Guinea – and in considerable numbers, it seemed, given Aunty Puss’s friends who were ‘girls I went away with’. They organised special occasions like reunions, which took lots of preparation and created huge enjoyment.

Above all, they loved to gather on Anzac Day, an annual event preceded by high anxiety over whether it would rain or be too hot or whether uniforms would fit. Medals were polished, seams adjusted. Aunty Puss (Major Dorothy Campbell SFX3050) had a wide row of medals, including a ‘very special one’ called the Royal Red Cross. Her Anzac Day began at the dawn service. She was a march marshal for years, laughing over her impossible task of achieving a straight line of ‘returned sisters’ front and rear. A long lunch and presumably countless stories followed.

We watched on television waiting for the nurses to march past. They were always gone in a flash, neither the camera nor the commentary giving them the attention we thought they deserved.

That was about all we knew until my aunt died in 2006, aged 96. It was only then we saw the diaries she had kept during the war and her photograph albums. They record her daily life as an army nurse from 1940 to 1945, or more accurately part of it. There was little about nursing duties beyond shift times – ‘very sick boy’ was a detailed comment. She wrote instead about conditions in the desert, tropics, and exotic Alexandria, about her social life and travels in the United Kingdom, Egypt and Papua and, at times, about the practicalities and frustrations of life in the army.

Deciphering her entries and photo captions has led to a fascinating journey in the Australian War Memorial and National Archives. The official hospital diaries have helped reconstruct her working days. Government files show the cumbersome, bureaucratic way the army dealt with the personnel issues of nurses such as marriage (completely prohibited until 1942), officer status and pay. Newspapers of the day show the extraordinary public sentiment about the nurses who looked after ‘our boys’ in their hours of need.

Now, as part of Australians’ fascination with the nation’s military past, new books are being published and research is being conducted on Australia’s army nurses beyond the few whose stories have already been told and retold, the prisoners of war. The Australian War Memorial’s exhibition, Nurses: From Zululand to Afghanistan, on show from December 2011 to October 2012 and likely to tour, is another reflection of this interest.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial

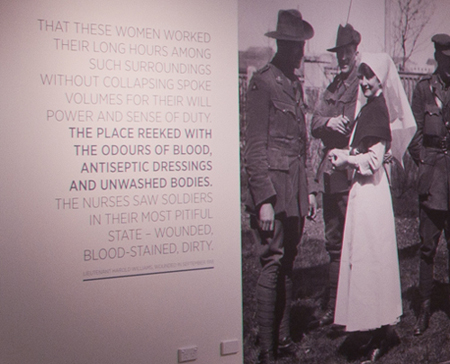

As its title suggests, the exhibition depicts Australian nurses who have served overseas with Australian forces in conflicts from the Zulu War (1879) to Afghanistan (present day). It takes the visitor through the Boer War and the 1914–18 war, then the 1939–45 war, on to the Cold War conflicts from Korea to Vietnam, and finally to recent humanitarian and peacekeeping operations. Each section includes an introduction, personal stories and artefacts.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial

The artefacts are mainly photographs, diaries and letters, war art, personal items and medals, most from the War Memorial’s existing collection. Several items, such as the patient’s ‘hospital blues’ uniform from the 1914–18 war, were made especially for the exhibition, reconstructed from photographs or fragile artefacts. The War Memorial’s small collections from recent conflicts and peacekeeping operations are supplemented by items on loan from currently serving personnel.

The exhibition has a chronological structure, designed to capture both continuity and change in nursing techniques and nurses’ lives in the army, navy and air force over more than a century. The kit carried by current medical personnel (virtually a hospital in a backpack) makes an astonishing contrast with the equipment and remedies carried by the early nurses in their pockets. Small items such as Betty Jeffrey’s pencil from the prisoner of war camp and the array of medals and decorations are especially poignant, as are several uniforms worn in the field.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial

Survey exhibitions such as this, which cover numerous conflicts, theatres and decades, present a real challenge to curators in terms of selection of material, themes depicted and subliminal messages conveyed. In reviewing them, it is tempting to focus on what has been left out rather than the impact of what has been included. Moreover, it has been mounted in a museum whose stated purpose is to commemorate service and sacrifice. Criticism of an exhibition in such a location can be misconstrued as disrespect for those who served or even those who seek to tell their stories.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial

Having said that and declared my personal and professional interest in army nursing, I enjoyed the exhibition but was disappointed in it for three main reasons.

First, the text of the exhibition is overly brief and superficial, both overall and for individual items. The introductions on panels for each section seem more focused on the conflicts than the nurses. Thus there is little sense throughout the exhibition of who the nurses were and why they enlisted, the restrictions they endured (e.g. marriage, status and pay), the opportunities they had for travel and sightseeing or the discomforts and hardships they faced.

In fact, the exhibition website and, to a lesser extent, displays in other Australian War Memorial galleries contain a good deal of additional material on nurses, but nowhere in this exhibition could I see a label prompting me to seek out further information.

The problem is not simply a matter of space. The exhibition struck me as surprisingly old-fashioned and static, my second disappointment. Digital technology could have been used to convey images and information without consuming much physical space. Engaging slide presentations on particular themes, such as digitised extracts from letters and diaries, nurses as travellers and tourists, changes in uniforms over time, a selection of nurses’ ‘happy snaps’ to complement the preponderance of official pictures, and/or the introduction of men into nursing could have energised the exhibition. The resources are certainly to be found in the War Memorial’s collections.

Technology is limited to two soundscapes on continuous loop. One comprises readings from diaries of nurses from the 1914–18 war. The readings seemed too long to hold visitors’ attention. The other is a detailed description of the contents of a current medical pack. It was too technical for me but for a friend who had served as a nurse in Vietnam it was the must-see item in the whole exhibition.

It is an intrinsic part of the Australian War Memorial’s mandate to commemorate service and sacrifice. My aunt and her nursing mates whom my sister and I knew were proud of their service and of their professionalism. They would have enjoyed the exhibition, been fascinated by its depiction of their uniforms and techniques, so modern compared with their predecessors and so antiquated compared with today’s military nurses, been pleased to be accorded interest and even admiration for their skill and commitment, been relieved to have escaped the privations of captured nurses.

But her diary entries and photos leave me with no doubt at all that Aunty Puss (and her mates) would have felt that the exhibition tells only part of their story. They would have instantly dismissed notions of sacrifice or indeed of devotion. They would have wanted the photos and artefacts to illustrate how they dealt with daily practicalities of keeping uniforms starched, stockings in good repair and hair washed, how they had opportunities to sightsee in places they had only dreamt about, how they enjoyed tennis and golf games between shifts on duty, sherry parties and dances in the evenings. Moreover, they would have pointed out that very few of them were close to enemy action or in great danger, that they were more likely to nurse troops with malaria than a gunshot wound.

Hence my third disappointment in the exhibition: that it tends to sentimentalise and mythologise military nurses. Mythology and sentimentality are welling up around Anzac Day and the commemorations. Distance from the events and the loved ones who were involved in them seems to make the heart grow fonder and the mind less acute. The histories written and the exhibitions mounted at the Australian War Memorial and elsewhere have a vital part to play in forthright analysis and dispelling hagiography.

photograph by Steve Burton

Australian War Memorial

The exhibition deliberately takes up the theme of the stained glass window in the War Memorial’s Hall of Memory in which a nurse depicts ‘Devotion’, one of the personal qualities of Australia’s servicemen and women. A panel at the entry and/or exit to the exhibition, pointing out that nurses possess not only devotion but also the other personal, social and fighting qualities depicted in the Hall of Memory (resourcefulness, candour and so forth), might have lifted the exhibition out of cliché into exploration and critique.

Janet Scarfe is an adjunct research associate in the School of Historical Studies, Monash University. She has a strong personal and professional interest in the Australian Army Nursing Service in the Second World War.

| Exhibition: | Nurses: From Zululand to Afghanistan |

| Institution: | Australian War Memorial |

| Curatorial team: | Robyn Siers (curator), Joanne Smedley (Assistant Curator), Danielle Cassar (Military Heraldry and Technology Advisor |

| Exhibition and graphic design: |

Arketype |

| Venue/dates: |

Australian War Memorial, Canberra 2 November 2011 to 17 October 2012 See website for touring dates |

| Floor space: | 320 square metres |