by Stefan Petrow

A common criticism of folk museums in Britain was that they 'had not only denied people their history, but had also sanitised it of the dissent and diversity that were part and parcel of both the rural and urban social scene'.[5] Some might see the men and women behind the formation of Narryna as elitists similarly intent on sanitising, idealising, perverting, whitewashing or even demeaning history by marginalising what they regarded as unsavoury aspects of Tasmania's past. But this is to ignore the fact that the process of not discussing convict origins in public or in private and the desire to wipe away the 'convict stain' had pervaded Tasmanian society since the end of transportation in 1853.[6] When fire swept through the old Port Arthur penal settlement in the 1890s few people cared; fire was welcomed as a 'purifier' of a 'tainted past'.[7] By at least the 1920s 'dread of the shameful past had died down' and little interest was shown in the convict past.[8] Academic Dennis Altman remembered that the 1950s was a period when 'those of both convict and Aboriginal descent denied it'.[9] Thus the 'cult of forgetfulness' or of 'disremembering', which anthropologist WEH Stanner argued was applied to the Aborigines in Australian history, worked equally well for Vandiemonian convicts.[10]

What the founders of the Van Diemen's Land Memorial Folk Museum (VDLMFM) wanted to represent was something more positive — a new-found interest and pride in the non-convict aspects of Tasmania's past. In highlighting the achievements and lives of the pioneers, they were not so much sanitising the past, but seeking to place their own 'construction upon history', as all museums tend to do, indeed as all historians do.[11] Those enthusiasts celebrated a version of history that struck deep chords in the hearts if not the minds of locals and tourists alike, mainly because of the diversity and richness of the collection. On one reading the collection transcended gender, age and even class. While it was located in an urban, middle-class house, it went some way to acknowledging 'the importance of the everyday lives of ordinary working people' in the tradition of European folk museums.[12] The progenitors of the VDLMFM would certainly have agreed with Eric Dunlop, Australia's leading advocate of folk museums, that folk museums would 'help foster an appreciation of and pride in local institutions and achievements'.[13] It was more than coincidental that the museum was established after the Tasmanian Government had belatedly begun to develop the convict settlement of Port Arthur as a tourist site from the late 1940s.[14] Certainly heritage bureaucrat and author Michael Sharland, who helped secure Narryna as a folk museum, wrote his book about Tasmania's colonial buildings, Stones of a Century, 'to modify the centrality of convictism in Tasmania's image'.[15] The government won the battle, as Port Arthur received much public funding and became the island's premier tourist resort by the mid-1960s and small community-run museums received increasingly less support from the Department of Tourism.[16]

Basing my analysis on the minutes of trustee meetings and other archival sources, newspapers and visitor books, I will proceed by first investigating the idea of the folk museum and establishing the historical and tourism context into which the Van Diemen's Land Memorial Folk Museum was born. I then examine the initial aims of the museum, how visitors reacted to the museum and how museologists assessed its significance.

Reacting against the 'violent changes of modern life', the first folk museum was the Nordiska Museet, established in 1873 by Swedish educationalist Artur Hazelius.[17] The most famous folk museum was the Swedish open-air museum at Skansen, which Hazelius opened in 1891. Skansen attracted many visitors and inspired the formation of folk museums in other parts of Europe and America. Britain was slow to develop folk museums. The first was established in 1936 in a church on the island of Iona by Miss IF Grant, who sought to preserve 'the old Highland way of life'.[18] But folk museums in Britain really flourished after 1945, usually in urban centres and in buildings of 'national, historic or architectural interest', which were threatened with 'decay, demolition or vulgar alteration'.[19] Perhaps the most famous was St Fagan's in Cardiff, a Tudor mansion whose rooms were used to display exhibits from 1948.

The purpose of a folk museum was to collect, conserve, study and exhibit 'the artefacts and vernacular architecture representative and evocative of the region in which it was located'.[20] Folk museums preserved 'the rapidly disappearing homely objects of everyday life', which usually had 'very little intrinsic value' but which 'played an important part in communal activities and development'.[21] The varied objects included 'domestic utensils and implements, furniture and fittings, costume and clothing, leisure time diversions, tools of all kinds and the products that came from skilled hands'. The objects were not just preserved, but at least in part displayed in a house of the period. Thus the 'enthusiasts and visionaries' who founded folk museums sought to create 'a living atmosphere — one which will stimulate the onlooker and lead to positive results'.[22] The aim of exuding 'liveness and liveliness' was achieved by fitting out buildings with 'furniture, utensils and all the domestic trappings of everyday use, artistically and functionally arranged so as to suggest that use has only momentarily been suspended — that the unseen inmates may return at any minute'.[23] Unlike other types of museums, labels were not appropriate in 'a building supposed to be lived in' and even 'simple statements of provenance, period, and type of dweller' were 'best kept just beside the entrance'. Details of objects could be included in a guide book. According to George Thompson, first director of the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, Hazelius saw folk museums as:

not only an exposition but an environment comprised of local cultural history which would bring people together in an atmosphere of shared tradition, thus encouraging them, through a new knowledge of their past, to sense a new pride in their past and in themselves as its inheritors — a pride based on fact, not fancy; a pride conditioned by a humility of self-understanding as opposed to a pride inflated by ignorance and self-delusion.[24]

In common with other history museums, folk museums played a powerful role in 'shaping the public's perception of the past'.[25] As local museums, they were 'central to understanding the forces that create communities' and provided in 'authentic detail a material cross-section of the daily life of the people'.[26] As we will see, the trustees of the VDLMFM drew on this tradition of folk museums in Europe, but local influences also lay behind the museum's formation and those influences need fuller explanation.

In the 1970s and 1980s some historians claimed that Tasmanians lacked interest in their history or attempted to distort it. In 1978 historian Lloyd Robson suggested that the convict inheritance lived on 'in the minds of many Tasmanians' and reinforced 'their determination to live down their past and pervert their history by stressing respectability'.[27] In 1983 feminist historian Kay Daniels thought that Tasmanian society was 'still uncomfortable with its past' and saw 'its history as in some ways marked by a shameful inheritance'.[28] Undoubtedly, these claims have some force. The 50-year period after Tasmania's settlement in 1803 left an indelible mark. Its origins as the penal colony of Van Diemen's Land and the demise of its Indigenous people cast a shadow over its later history and encouraged cultural amnesia. But, as the second most important colony, it benefited from Imperial money: the colonists were enterprising, the economy prospered, and in the late Georgian and early Victorian period many fine public and private buildings were erected throughout the island. There was much to celebrate as well as to lament.

Robson's and Daniels' assessments of Tasmanians' lack of interest in their history failed to acknowledge that a marked shift in historical consciousness occurred in Tasmania between 1931 and about 1960.[29] In this period historical societies, professional societies and community bodies sought to preserve, protect or highlight Tasmania's historical traditions and buildings. Enthusiasts of this predominantly middle-class movement commemorated the exploits of explorers, pioneers, soldiers, sailors and businessmen. They worked to preserve buildings, ships and historic documents, erect monuments, lay plaques and commemorate significant anniversaries. They celebrated a positive version of the past and largely ignored darker deeds and hoped to capitalise on the post-war boom in cultural tourism. These aims culminated in the island's Sesquicentenary celebrations, beginning in 1953 when the possibility of establishing a folk museum at Narryna, representing the social history of the island's pioneers, was first seriously raised. The Sesquicentenary had consciously sought to minimise reference to 'the two Vandiemonian spectres, convicts and Aboriginals' and the founders of the folk museum adhered to that aim.[30]

The 1950s also witnessed a drive to protect Tasmania's 'wealth of beautiful buildings', especially of the Georgian period, which conferred 'an old-world stateliness on city, town and country'.[31] Country areas were dotted with 'stately dwellings' and in the cities could be found 'elegant mansions' and 'fashionable villas'. In 1955 the annual conference of the Australian Institute of Architects was held in Hobart and delegates were 'impressed by the dignity and charm of Tasmanian buildings'. They urged preservation of 'the early colonial style architecture'. The Tasmanian Government took a first step by acting on the Scenery Preservation Board proposal to acquire the farming homestead Entally House at Hadspen as a 'national house'. But the government lacked the funds to acquire all the fine buildings that justified preservation and community groups had to fill the breach. The activists seeking to turn Narryna into a folk museum hoped their proposal would protect that gracious building and be the next step on the road to forming a National Trust in Tasmania to protect other 'beautiful colonial buildings'.[32] They even hoped that the National Trust, established initially in Hobart in November 1954, would establish its headquarters in Narryna, but this did not happen.[33] The Hobart-based Trust was ineffective, perhaps because so many of its members had their hands full developing Narryna as a folk museum. In 1960 another body registered itself as the National Trust (Tas) Ltd in Launceston and took control of the movement to preserve historic buildings.[34]

The link between historical consciousness and tourism became clearly established in the post-1945 era. After the war Australia witnessed an upsurge in holiday travel and in the 1950s Tasmania's 'share grew gradually'.[35] A Select Committee on the Tourist Accommodation Loans Bill 1959 thought Tasmania could get a larger share and, urging Tasmanians to become 'completely tourist conscious', recommended that government pursue the 'enormous possibilities' for the development of tourist attractions.[36] As air and sea links improved, tourist numbers increased in the 1960s and historical attractions, especially 'the preserved colonial homes', became ever more popular.[37] The VDLMFM was established at a propitious time when tourism numbers were beginning to mount, politicians were more inclined to support ventures likely to appeal to tourists and interest in Australia's past was beginning to develop. Thus the VDLMFM was one of the 'hundreds of small museums' that had been founded at the 'grass-roots' level from the 1950s to the 1970s, which the Pigott inquiry into museums described in 1975 as 'one of the most unexpected and vigorous cultural movements in Australia' in the twentieth century.[38] With this context in mind let us turn to the origins of the VDLMFM and the aims of its founders.

Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, State Library of Tasmania

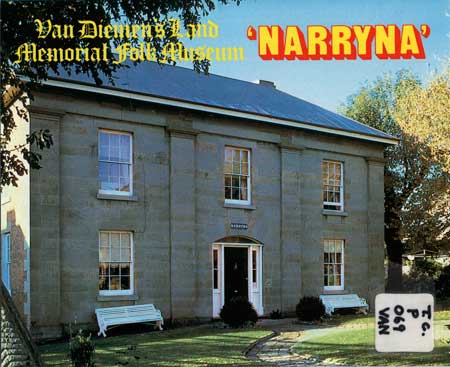

In the 1940s Narryna was used as a boarding house and later as an after-care home for female tuberculosis patients, but in 1954 it was rumoured that the government proposed to sell the building as a warehouse or for 'industrial purposes'. This galvanised Michael Sharland, secretary of the Scenery Preservation Board, which had responsibility for preserving buildings of historic interest. As Narryna was 'among the top list of properties worthy of preservation both for its architectural features and historic interest', Sharland persuaded his board to proclaim it a scenic reserve.[44] Further investigation revealed that the government intended to use the building as an administrative block for a chest clinic and the board asked the Health Department not to make any structural changes that might 'spoil' its 'character'.[45] In June 1954 the Battery Point Progress Association approached the board, seeking its support for a plan to turn Narryna into a folk museum.[46] As Battery Point was 'the home of antiques, both domestic and nautical', the association argued that it would not be difficult to stock the building with suitable items. This proposal received support from the chief secretary Alfred White, who was a member of the Battery Point Progress Association, and the trustees of TMAG, who agreed to loan any 'suitable exhibits' held in store.[47] The Tasmanian Historical Research Association supported the use of Narryna as a folk museum.[48] Architectural historian Harley Preston told a meeting of the association that buildings like Narryna could be used 'profitably for some civic purpose' such as a museum and were valuable as 'tourist attractions, educational exhibits, historical mementos and for their intrinsic aesthetic value'.[49]

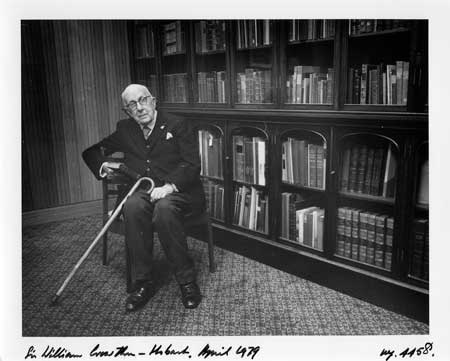

Mainly due to the lobbying of White, in early 1955 the government agreed to spend £3000 in repairing and restoring Narryna to its 'old world glory', but appointed eight trustees to set up and oversee the running of the museum, with daily management being the responsibility of a resident caretaker.[50] Visitors would be charged for admission and tea could be purchased. The trustees had to raise £20,000 as a trust fund to maintain the museum and building, which would relieve the government of providing funding. The eight trustees were Dr William Crowther as chairman, Amy Rowntree as secretary, Sir Geoffrey Walch, Dr WV Teniswood, Alderman Mabel Miller MHA, FC Wolfhagen, Captain Harry O'May, and IG Anderson as honorary architect. All were prominent in professional or historical circles and had impeccable middle-class credentials.

This 'small but enthusiastic group of people' worked hard to establish a folk museum in Narryna as 'a permanent memento of the Sesquicentenary'.[51] They 'recognised the need to collect and preserve objects of importance' from Tasmania's 'pioneer' past before they became lost or deteriorated and, as TMAG lacked space, to display them in a specialised museum for public viewing.[52] They wanted to represent 'the whole way of life' of the urban and rural colonists from 1803 to 1853.[53] The public figurehead was Crowther, who had been appointed a trustee of TMAG in 1919 as a result of his growing interest in Australiana.[54] He became an obsessive collector of books, manuscripts, prints, charts, maps, paintings, scrimshaw and other materials associated with Tasmanian history, especially its maritime and medical history and its anthropology. Crowther became an authority on the Tasmanian Aborigines, giving the 1933 Halford Oration on 'The passing of the Tasmanian race' and writing eleven papers on their customs and history.[55] His 'tenacity' as a collector and 'knowledge' of Tasmanian history were crucial to the setting up of the folk museum.[56] State Library of Tasmania publicity officer David Hinley described him as 'a truly great Tasmanian patriot', but librarian, Tasmaniana specialist and later fellow trustee Geoffrey Stilwell claimed Crowther '"grabbed" from other people' and exploited his visits to his older patients to acquire valuable books and other items.[57] Crowther kept 'anything he really liked for himself' and there were items in the Crowther Collection at the State Library of Tasmania that 'probably should have originally been given to the Folk Museum'.[58]

During the setting up phase in 1956 the executive committee discussed whether confining the exhibits to the Van Diemen's Land era was justified, but they agreed that the size of Narryna would only accommodate exhibits 'primarily' from the period 1803 to 1856.[68] One of the committee members, Dr William Bryden, director of TMAG, defined a folk museum as giving 'a true impression of the life lived by the people of the past'. They decided 'to devote each room to some aspect of life' and planned rooms devoted to Hobart, shiplovers, women, costumes, fine arts, photographs and pictures and kitchen items and rural life. Gwen Cox questioned whether the proposed name Van Diemen's Land Folk Museum might 'prove unattractive' to tourists (she did not explain why) and suggested that 'a more popular' name be selected.[69] Although she was overruled by the other executive committee members, all agreed on the need for 'an attractive brochure for Tourist Bureaus throughout Australian cities and Tasmania'. Miss Joan Perkins, who became a stalwart of the museum, obtained for the executive booklets illustrating two American folk museums as a model for their own brochure.[70]

Crowther, the Rowntrees and other women who formed a Ladies' Auxiliary worked feverishly to raise money and to approach pioneer families for loans or gifts of historical treasures to exhibit.[71] Suitable historical material that could not be displayed in TMAG and part of the extensive collection of the Shiplovers' Society of Tasmania could be housed at Narryna. The trustees intended to display only those articles which had, as Rowntree put it, 'a direct connection with pioneers' from the first 50 years of settlement.[72] They also intended to 'feature women's interests' through displays of period costumes, hobbies and crafts and hoped to receive support from women's organisations in selecting and gathering exhibits and forming committees to run the museum.[73] They found that the £3000 government grant did not cover all restoration expenses and, using their own money and donations from the Country Women's Association, Battery Point Progress Association, and businessman Leonard Nettlefold, spent another £1000 on interior painting and alterations.[74]

The idea of forming a folk museum for pioneers was received with enthusiasm. The Saturday Evening Mercury noted that folk museums seeking 'to embody the history of a people' were 'rapidly gaining popularity' in Europe.[75] Tasmania was 'rich in history and the museum will seek to pay tribute to the courage and fortitude of its pioneers'. Folk museums were 'centres of culture and education' and would 'awaken the public to the value and quality of beautiful old things and the need to preserve them'. As the trustees had hoped, the folk museum received support from the Country Women's Association. Citing successful British folk museums in Bristol and York, the CWA organ the Tasmanian Countrywoman supported the idea of 'a memorial to the pioneer men and women whose courage and initiative by land and sea built up for us this pleasant way of life'.[76] It affirmed the need to place Tasmania's many historic 'treasures' under proper care before they were lost forever. The secretary of the CWA, Miss Elizabeth Perkins, later became an associate trustee of the museum along with Mrs Gwen Cox and Mrs SC Burbury.[77]

With no criticism worth mentioning, the trustees confidently set about preparing Narryna for use and telling the Tasmanian public of their plans. In a letter to historian and fellow bibliophile George Mackaness, Crowther praised the efforts of his 'eager and kind' female supporters, who made 'light of work and obstacles'.[78] They were clearly indispensable to the museum's success. On 11 May 1957 a ten-day colonial exhibition was held to raise funds and through donations from local pioneer families who settled in the first 50 years became 'the most comprehensive historical collection assembled in Tasmania'.[79] The fine furnishings, exquisite china and glassware, Sheffield plate and 'delicate pictures' were brought with the first emigrants and showed 'the beauty with which so many of the settlers surrounded themselves'.[80] The furnishings and antiques were mostly not 'shown as museum pieces, but arranged as if the rooms were in daily use'. As the 'beautiful things' were 'so carefully preserved and lovingly cherished to the present day', visitors became 'aware of the sense of continuity with the past'.[81] Far from being 'fragile creatures, given to swooning at the slightest provocation', Gwen Cox felt that typically a pioneer woman must have possessed 'a strength of spirit' to insist on bringing to Van Diemen's Land, where her first home might be 'a slab hut', 'a "taffety" gown, its tiny waist and wide crinoline skirt showing her to have been of diminutive stature'. If the exhibition was any guide, the folk museum would become, wrote Cox, 'a tourist attraction unsurpassed in any other Australian city' and provide 'a link with the early days of settlement, which will have inestimable value for the years to come'. The exhibition raised £700 and created 'State-wide interest' in the museum.[82] Crowther pronounced the exhibition 'an extraordinary success' and described Hobart as 'at the moment all V[an] D[iemen's] Land minded'.[83] The trustees saw the exhibition as a vindication of their labours.

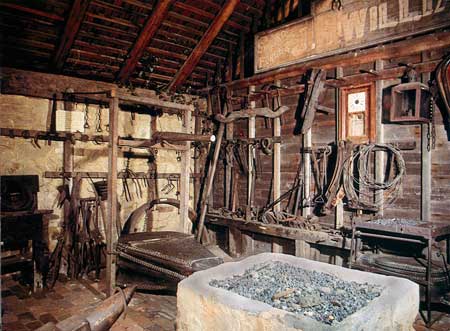

In mid-1957 the trustees printed a pamphlet that explained their aims. Following the example of folk museums in England and Europe, their museum would 'illustrate through objects the Social History of our people'.[84] In each passing year documents and objects 'valuable in themselves or for the history they demonstrate are being lost, destroyed or sold out' of Tasmania and the trustees intended to supply a place where they 'may be collected and guarded'. Initially, two rooms would show 'early family living conditions and displays of valuable furniture'. Other objects would be collected to 'illustrate the customs, vocations, hobbies, habits and activities of our pioneer activities'. The rooms would focus on particular themes such as shipping, costumes and women's occupations. Outside, a stable would display 'relics of our early rural activities and illustrations of some old crafts'. The central purpose of the displays was to provide education for 'present and future generations in the social history of a people'. Stress was laid on commemorating 'the valuable contribution' of the men and women 'who suffered danger and privation during the pioneer years'. No mention was made of convicts and the museum was dedicated to the memory of the descendants of pioneers 'who served in either of the two world wars'. The link with war service seems not to have been discussed in the original planning phases of the museum, but, as memories of the war were fresh in the minds of the Tasmanian people, the dedication added to the museum's appeal. The trustees hoped their museum would 'grow into a national asset and a major attraction to visitors to the State'.

The 'splendid women's auxiliary' worked hard to prepare the VDLMFM for opening on 30 November 1957.[85] The Chief Secretary Alfred White officiated and declared that Tasmania had to provide 'more in the way of tourist attractions' and that turning Narryna into a folk museum 'would be an important step in that direction'.[86] Tasmania had depended too much on 'what nature had endowed it, and too little has been done to create other interests'. On a recent visit to Europe, White had been impressed with the representation of folk life in Sweden's Northern Museum and the Welsh National Museum at St Fagan's Castle, where craftsmen showed their skills. In offering his advice to the trustees, White followed Henry Balfour, the English museum curator, who stressed that folk museums 'should present objects capable of yielding some lessons in our time' and present 'arts, industries and customs which by their truly national character afforded the firmest foundations for the nation's life and future'. White marvelled at how 'the skill and workmanship' of the early settlers were applied to Tasmanian trees like Huon pine to create furniture such as that on display in the new museum. Volunteers kept the museum running smoothly for the next 50 years, especially members of the Ladies Committee, who received many encomiums.[87] They made sure that the role of women was not neglected in the museum.[88]

Without objects museums cannot exist, but we should not, as Samuel Alberti has argued, 'attribute too much power' to the objects displayed in museums or to the aims of curators or managers.[125] He directs our attention to the interaction between the objects and the people who view them, to 'the relationship between thing and observer', and to 'the reasons, experiences and sensations of visiting'. After all, the trustees had consciously wanted to make an impact on tourists and locals by shaping their view of Tasmanian history. How did visitors react to the VDLMFM? We should be aware that people visit museums for various reasons and museums do not deal with 'one uniform audience each individual, each group brings with them different backgrounds, different levels of knowledge, different interests, different dynamics'.[126] These all shape how people 'interact' with the objects on display in complex ways. In the case of the VDLMFM we can identify different categories of visitors with different motives for visiting, such as journalists, heritage experts from abroad and those members of the general public who signed the visitors' book.

Women journalists were especially drawn to the museum. One journalist named Elizabeth, who appears to have written for a Melbourne newspaper in the early 1960s, thought entering Narryna was 'to take an unforgettable step back in time, to discover the charm and the elegance of another way of life which is gone forever'.[127] She was persuaded that the furnished rooms represented 'an authentic picture of life as lived by a well-to-do settler' in the 'adventurous pioneer days' before 1850. Pat Weetman told readers of the New Idea in 1966 that if they were 'fascinated by the fun of finding out how women lived a century ago', they should visit the museum.[128]

Visitors from Britain were equally enthusiastic. In 1959 heritage specialist Robin Bailey visited Hobart on an inspection tour of historical buildings sponsored by the National Buildings Record in London. She was 'impressed by the quantity and quality of exhibits' collected in 18 months.[129] She commented favourably on the downstairs rooms 'furnished as if still in use', which were 'far more attractive than show case exhibits'. She noted that the insurance plate on an outside wall and the set of carpet bowls were 'much sought after in England'. In 1961 John Steegman, a British authority on fine arts and architecture, visited Tasmania to participate in a seminar on The Victorians sponsored by the Adult Education Board and the University of Tasmania. The seminar was held at Narryna and Steegman praised the representation of 'the daily life' of settlers, which he found preferable to presenting 'a collection of beautiful things'.[130]

The reactions of ordinary visitors are more difficult to discern. The VDLMFM's annual report of 1979–80 noted the many 'favourable comments' recorded in the visitors' book on 'the variety and standard of displays', but regretted that these comments could not 'be submitted as documentary evidence of the success achieved'.[131] Although visitor books have long been used to gauge visitor responses, they have been underutilised by scholars, who regard them as a problematic source.[132] As Tamar Katriel has argued, comments in visitor books are 'self-selected, appreciative responses given out from guests to their hosts, thereby affirming that the museum has accomplished its rhetorical mission'.[133] The comments represent 'an audience-contributed gesture of closure' and not 'well-balanced feedback on their museum experience'. Typically few critical or indifferent responses are recorded and they usually suggest improvements to 'one aspect of the display or another but never questioned the value or relevance of the enterprise as a whole'. While writing in a visitor book might be seen as 'part of the visiting process or ritual', it is a voluntary act and unlike other sources provides the views of many individuals in a public way.[134] They are one way of discovering how ordinary people relate to history and their comments should not be dismissed too lightly, Katriel's cogent arguments notwithstanding.

Certainly, the visitor books convey the immediate reactions of many patrons. In the visitor book for the period 1958 to 1961 the exhibits were typically described as 'Most interesting', 'Very beautiful', 'Most educational', 'Charming' and 'a tourist treasure'.[135] Some people thought they had been taken 'back in time' and one person suggested that it was one of 'the very few places' in Australia 'where one can see the beginning of white civilisation'.[136] Some visitors thought the VDLMFM compared favourably with similar attractions in Britain and some items, such as the tool boxes, were not held in museums there.[137] One English visitor described Narryna as 'the most wonderful place I have visited'.[138] In February 1992 one visitor commented that the displays made 'history come alive' and another in April 1996 that the museum was 'Very authentic. Even smelt right!'[139] Similar comments were made in the extant visitor books to 2007. Generalities in all the visitor books far outweighed specifics, but sometimes, as with the tool boxes, particular aspects of the collection were mentioned. Others to rate a mention included the 'Glorious costumes', 'the tapestries', 'the old Anchor', 'the needlework', the toys, and the blacksmith shop.[140]

No one commented on the absence of convict history and only one visitor noted that there was 'practically no reference to Aborigines'.[141] Only a few visitors mentioned how hard life must have been for the servants.[142] No one felt 'duped' or had their 'expectations thwarted' by the representation of history on display.[143] Although one might conclude that the VDLMFM achieved its 'rhetorical mission', dissatisfaction was expressed with some elements of the museum.

In 1983 the VDLMFM won the best museum in the open category in the first Tasmanian museum awards.[144] This was a notable achievement as almost 90 museums and related attractions were operating in 1983. Despite this award and the generally favourable comments it received, the museum also attracted criticism from visitors and museologists.

Some discordant notes were recorded in visitor books. One visitor from Canberra suggested in 1960 that a 'modest catalogue be prepared, if possible with exhaustive notes'.[145] This point was made more stridently by a visitor in 2005, who was thrilled at 'some wonderful pieces', but felt that the lack of labelling for 90 per cent of the exhibits and 'insufficient labelling' of the rest made 'what could be interesting rather meaningless'.[146] One visitor thought the exhibits suffered from 'insufficient display room' and that 'crowding' exhibits tended 'to distract attention from specific items on display, or alternatively tends to disguise others'.[147] The trustees were conscious of their deficiencies. In 1974 Bryden told the Pigott inquiry that the museum lacked the funds to employ 'trained people' to research the items in the collection.[148] He admitted that they had not compiled 'a thorough inventory, with complete details of [the] provenance etc of each item'. They also needed to employ someone 'trained in the methods of display'.

In May 1968 RE Clarke, managing secretary of the Tasmanian Tourist Council, reportedly attacked attractions such as Entally and Franklin House as 'nothing more than tourist museums'.[149] He claimed that such historical attractions 'lacked interpretation, presentation and atmosphere'. The VDLMFM was not mentioned, but there were signs that it had been moving away from the first decades of the island's history simply to attract tourists. This is shown by some of the incongruous objects it accepted. An example was one of the three barrels first used by Tattersall's Sweeps in the 1890s.[150] This was acquired in the early 1960s and proved to be 'a great tourist attraction'. In 1964 the firm of J and E Stalker stopped using their 45-year-old horse-drawn tip dray, which had been used to clean the streets of Hobart, and donated it to the museum.[151]

The most probing assessment of the museum came from Peter Mercer, Curator of History at TMAG. Mercer, who wrote a report for the trustees of TMAG when amalgamation with the VDLMFM was being discussed in 1983, had often visited Narryna and had given advice to the House Committee. As there were many more museums with 'very good historical and folk collections' in the 1980s than when the VDLMFM was established, Mercer thought it timely to review 'whether it should continue as a general repository of folk material' or whether it should 'cover a more specialised area of our social history'.[152] Mercer praised the 'farsighted' actions of the founders in assembling 'this fine collection', which 'in terms of rare and unusual items' placed the VDLMFM among the leading folk museums in Australia. The collection was so large that it greatly exceeded the available space. Mercer stressed that Narryna's 'special quality and charm' stemmed from 'the comfortable, middle class colonial atmosphere one feels on entering its doors'. Any reassessment of its role should focus on nurturing and developing this special quality so that 'the individuality of the house and the taste and aspirations of its former occupants can be brought to the fore with a high degree of authenticity and intimacy'. Mercer thought the exhibits should complement the house, which would become less 'primarily a repository for folk objects' than 'a capsule of "living history"'.

Mercer argued that the building, not the collection, should become 'the major exhibit' and this would necessitate a major review of the whole collection.[153] A review would investigate whether the objects were 'correctly displayed in the right context, or are displayed to the best effect' and whether all the objects were relevant to 'the daily functioning and daily needs and comfort of the occupants of a 19th century town house'. Mercer approved of amalgamating the VDLMFM with TMAG as this would promote the pooling of resources and exchanging of objects so that each museum displayed objects appropriate to its respective purposes. Mercer's suggested rationalisation was to make the Cottage on the TMAG site, built around 1811, represent 'the domestic side of living in the early years of settlement', the Bond Store at TMAG, built around 1824, to represent 'the experience of man, his activities and enterprises in Tasmania' from 20,000 BC to the early twentieth century and the VDLMFM to represent 'the social history' of Hobart in the 50 years after the cottage was built. Thus tourists and others would have to visit all three locations 'to gain the full experience and picture of Tasmania's history and its place in the world'.

Before that bold plan could be implemented Mercer thought the displays at Narryna could be improved and made a number of criticisms and recommendations.[154] Most rooms of the house contained model figures dressed in 'period costume in various attitudes of pose'. The models were designed to add 'atmosphere' to the rooms and to give 'the illusion that the house is still lived in by its colonial occupants'. This was a common aspiration of folk museums, but 'very few if any have really succeeded'. Even 'an immaculately prepared waxwork model' failed to offer more than a 'superficial' sense of realism, but the Narryna models were shop window models and, with their 1930s hair style, they looked 'ridiculous' modelling nineteenth-century dresses. It was confusing to be confronted in the nursery with children's dolls and '1930s models of children dressed in nineteenth century clothes'. Visitors entering a faithfully restored period room should feel that they were 'literally stepping back in a time machine, to the period they are witnessing'. They should 'feel the presence of the former occupants, not see them', but that was impossible when 'confronted with many obvious lifeless replicas'. Mercer recommended that model figures be removed from all period display rooms and be replaced by 'a changing and topical display' of costumes periodically in one of the 'formal or special display areas'.

Mercer suggested various modifications to the period rooms 'to bring them sharply into line with mid to late nineteenth-century fashions and tastes'.[155] For example, steel drapery display cabinets should be replaced with 'suitable domestic china cabinets, as funds permit'. In the old dining room the old-fashioned commercial display cases had 'grossly overcrowded "visual feast" displays', which tended to boggle the mind of the viewer rather than offer any instruction. The coach house appeared to be a replica built in the late 1950s or early 1960s, but it reflected 'the style and atmosphere of a 19th century rural barn rather than a city-dwelling coachhouse'. While the blacksmith's shop was 'a good example of reconstruction', it was not usually part of an average middle-class town house. Both outbuildings could be kept and improved for displaying exhibits. Mercer also suggested restoring the gardens to give a nineteenth-century appearance, 'using the many older varieties of flowers and shrubs that were popular at the time'. Helpful advice could be given by members of the Garden Historical Society. Finally, reflecting trends emerging in Britain, Mercer thought the term 'folk museum' was 'now done to death' and that a change of name, such as Narryna — Van Diemen's Memorial Museum of Social History, was overdue.[156] As noted earlier, the name was not changed to Narryna Heritage Museum until 1998 and, for financial reasons it seems, few of the other changes Mercer suggested were attempted.[157]

Some commentators criticised the lack of attention given to the convict associations of objects displayed at Narryna. Former Labor premier and newspaper columnist Bill Neilson questioned in 1984 the excessive emphasis given to the gentry and advised visitors not to overlook the objects that related to employees.[158] He pointed out that 'emancipated convict women' must have used 'the old fashioned kitchenware and utensils'. The snares and traps found among the farming tools must have been used by ex-convict trappers. But the trustees had always distanced themselves from convict associations. In 1964 the Museum Committee declined to accept a cat-o'-nine-tails because it did not 'come within our sphere'. It was later accepted by TMAG, which had a strong collection of convict artefacts.[159] In 1965 handcuffs and leg-irons were found in the loft and given to the exhibition of convict relics at Port Arthur.[160] Some of the items remaining in the collection did have an unacknowledged convict provenance. For an example, the craftsman of an armchair made from Australian blue gum and held together with wooden pegs, not nails, was thought to have been a convict.[161] In 1989 the trustees agreed to a request from Launceston's Queen Victoria Museum and loaned a convict-made clothes brush for its Convict Crafts of Tasmania exhibition.[162] The artists Costantini, Bull and Bock had been transported convicts, but — perhaps because they were 'gentleman' convicts, or perhaps because of the (monetary and snob) value of the works — the trustees would never remove their much sought-after paintings from the museum.

Despite their valuable attributes, folk museums fall prey to some of the historical fallacies that academic commentator Thomas Schlereth has attributed to all museums.[163] They convey a sense of progress and triumph against adversity but ignore failure and they look back nostalgically to 'a lost golden age' when consensus ruled and disagreement and conflict were absent. The past they represent is simple, not complex or ambiguous, and their version of the past was the most inspiring version. In their 'zeal to support the dominant cultural mythos', other versions of history are excluded.[164] As museum theorist Tony Bennett puts it, folk museums present 'an idealized depiction of social relations cast in the mould of a pre-Edenic organic community'.[165] They are 'populist rather than democratic in conception, finding a place for the lives of ordinary people only at the price of submitting them to an idealist and conservatively inclined disfiguration'.[166]

Visitors to Narryna have been, over the years, oblivious to the criticisms of academics and museologists and, on the evidence of visitor books, with very few exceptions seem to feel reassured, nostalgic and enthralled rather than repelled, antagonised or saddened by the simplified, untainted and partial version of history on offer. Perhaps the visitors to Narryna have sought it out, as heritage academic David Lowenthal describes the motives of visitors to American pioneer museums, 'not to re-enact their forebears lives, but to celebrate the differences from their own; to affirm their connection with a heritage, not to relive it'.[167] Or as American historian David Kyvig suggests, like most museum visitors, they attend 'to be entertained by the beautiful, the bizarre, the rare and the captivating'.[168] Whatever the reasons for visiting, the trustees can be seen to have succeeded in preserving many valuable artefacts and in representing their version of the past for the edification of future generations.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

2 The name was changed in 1998 to give the museum a more appropriate modern name, Van Diemen's Land Memorial Folk Museum (hereafter VDLMFM), Museum committee meeting minutes, 8 April 1998, Narryna Heritage Museum Hobart (hereafter NHM).

3 Linda Young, 'Memory, forgetting and invention in national identity: Australia's historic house museums', in Rosanna Pavoni (ed.), Historic House Museums as Witnesses of National and Local Identities: Acts of the third Annual DEMHIST Conference Amsterdam, 14–16 October 2002, DEMHIST, Milano, 2003, p. 103.

4 John Hirst, 'Pioneer legend', Historical Studies, vol. 18, October 1978, 316–37 (pp. 316–17, 330–1).

5 Gaynor Kavanagh, History Curatorship, Leicester University Press, Leicester, 1990, p. 49.

6 Henry Reynolds, '"That hated stain": The aftermath of transportation in Tasmania', Historical Studies, vol. 14, no. 53, 1969, 19–31; Alison Alexander, 'The legacy of the convict system', Tasmanian Historical Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 1998, 48–59 (p. 51).

7 Tom Griffiths, 'Past silences: Aborigines and convicts in our history-making', in Penny Russell & Richard White (eds), Pastiche 1: Reflections on Nineteenth-Century Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 21.

8 Alexander, 'Legacy', p. 55.

9 Dennis Altman, Defying Gravity: A Political Life, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, 1997, p. 12.

10 WEH Stanner, After the Dreaming, Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney, 1969, p. 25. In the 1950s the Tasmanian premier claimed that there were 'no Aborigines', despite the existence of Cape Barren Islanders; John J Cove, What the Bones Say: Tasmanian Aborigines, Science and Domination, Carleton University Press, Ottawa, 1995, p. 102.

11 Peter Vergo, 'Introduction', in Peter Vergo (ed.), The New Museology, Reaktion Books, London, 1989, p. 2.

12 Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory and Politics, Routledge, London, 1995, p. 117.

13 Eric W Dunlop, Local Historical Museums in Australia, Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1968, p. 2; for an elaboration of Dunlop's ideas see Nicole McLennan, 'Eric Dunlop and the origins of Australia's folk museums', reCollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 1, no. 2, September 2006, 130–51.

14 David Young, Making Crime Pay: The Evolution of Convict Tourism in Tasmania, Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 1996, pp. 132–7.

15 Michael Roe, 'Michael Sharland: For nature and heritage', Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers and Proceedings, vol. 55, no. 1, 2008, 44–63 (p. 53).

16 See the criticisms in a memorandum by GJ Dean, Director of Tourism, 29 October 1982, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

17 Kevin Walsh, The Representation of the Past: Museums and Heritage in the Post-Modern World, Routledge, London, 1992, p. 96.

18 L Bruce Mayne, 'The growth of British folk museums', The Amateur Historian, vol. 4, no. 1, 1957, 197–204 (p. 199).

19 Douglas A Allan, 'Folk museums at home and abroad', Proceedings of the Scottish Anthropological and Folklore Society, vol. 5, 1956, 91–120 (p. 102); JM Scotford, The Concept of a Folk Museum, Canberra and District Historical Society, Canberra, 1963, p. 2.

20 George Thompson, 'The social significance of folk museums', in Scottish Museums Council, Museums Are for People, Scottish Museums Council, Edinburgh, 1985, p. 33.

21 Allan, 'Folk museums at home and abroad', p. 91.

22 ibid., p. 115.

23 ibid., p. 116.

24 Thompson, 'Social significance', p. 33. Warren Leon & Roy Rosenzweig, 'Introduction', in

25 Warren Leon and Roy Rosenzweig (eds), History Museums in the United States: A Critical Assessment, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1989, p. xii.

26 Amy K Levin, 'Why local museums matter', in Amy K Levin (ed.), Defining Memory: Local Museums and the Construction of History in America's Changing Communities, AltaMira Press, Lanham, 2007, p. 25; Scotford, Concept of a Folk Museum, p. 3.

27 Lloyd Robson, 'Tasmania: A personal reflection', Meanjin, vol. 37, no. 2, 1978, 220–8 (pp. 221–2).

28 Kay Daniels, 'Cults of nature, cults of history', Island Magazine, no. 16, 1983, 3–11 (p. 3).

29 Stefan Petrow, 'Conservative and reverent souls: The growth of historical consciousness in Tasmania 1935–1960', Public History Review, vol. 11, 2004, 131–60; Stefan Petrow, 'In memory of ships: The Shiplovers' Society of Tasmania 1931–1961', The Great Circle, vol. 29, no. 2, 2007, 29–43.

30 Michael Roe, 'Sesquicentenary', Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers and Proceedings, vol. 52, no. 2, 2005, 107–18 (p. 110).

32 Amy Rowntree, 'Narryna Folk Museum', Bulletin, 7 September 1955, p. 25; Rowntree to Chief Secretary, 24 January 1957, Premier and Chief Secretary's Department General Correspondence, (hereafter PCS) 1/352/308, Archives Office of Tasmania, Hobart (hereafter AOT).

33 Petrow, 'Conservative and reverent souls', p. 151.

34 Tim Jetson, In Trust for the Nation: The First Forty Years of the National Trust in Tasmania, 1960–2000, National Trust of Australia [Tasmania], Launceston, 2000. <BR />

35 'Facts and figures on the Tasmanian Tourist Industry', about 1964, Tasmanian Government Tourism and Immigration Department General Correspondence AA 494/1/119, AOT.

36 Tourist Accommodation Loans Bill 1959 (no. 49): Report of Select Committee with Minutes of Proceedings and The Bill as Reported, Journals and Printed Papers of Parliament (Tasmania), vol. 163, 1960, Paper 12, pp. 4, 9.

37 Examiner, 14 May 1966, p. 3; AC Atkins, Minister for Tourists, 'Tourism', typescript article, 26 January 1967, AA 494/1/120, AOT.

38 Museums in Australia 1975: Report of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections, including the Report of the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1975, p. 21.

39 Saturday Evening Mercury, 14 May 1955, p. 19; Peter Mercer, Built for a Merchant or the History of a Colonial Gentleman's Residence: Comprising the Story of the House and a Guide to its Collections, Narryna Heritage Museum, Hobart, 2002.

40 Amy Rowntree, 'Rich memorial in stone', Saturday Evening Mercury, 12 January 1957, pp. 4, 11.

41 Tasmanian Government Tourist Department, Historic Battery Point, Hobart, Government Printer, Hobart, 1966.

42 Report to the Trustees of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery on The Van Diemen's Land Folk Museum by Peter Mercer, 25 February 1983, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

43 Mercer, Built for a Merchant, p. 1.

44 Scenery Preservation Board (hereafter SPB) Minutes, 19 February 1954, AA264/4, AOT; Sharland to Secretary for Lands, 23 February 1954, Sharland to Minister for Lands and Works, 23 February 1954, SPB General Correspondence, AA 577/1/131, AOT.

45 SPB Minutes, 3 May 1954, AA 264/4, AOT; Sharland to Secretary Department of Public Health, 11 May 1954, AA 577/1/131, AOT; Michael Sharland, Oddity and Elegance, Fullers Bookshop, Hobart, 1966, p. 32.

46 SPB Minutes, 25 June 1954, AA 264/4, AOT; Rowntree to Sharland, 11 March 1954, AA 577/1/131, AOT.

47 Minutes of the Trustees of the Tasmanian Museum, 4 March, 6 May, 1 July 1954, PCS1/256/308, AOT; Minutes of the Trustees of the Tasmanian Museum, 3 March 1955, PCS1/299/308, AOT.

48 Bob Sharman, 'The Tasmanian Historical Research Association: Notes on the beginning of the association', Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers and Proceedings, vol. 42, no. 4, 1995, 214–22, p. 218.

49 Harley Preston, 'Early domestic architecture in Hobart', Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers and Proceedings, vol. 5, no. 4, 1957 (67–72), p. 72.

50 Lawless to Rowntree, 18 January 1955, Cosgrove to Rowntree, 27 July 1955, PCS1/299/308, AOT; Saturday Evening Mercury, 14 May 1955, p. 19; Angus Small, 'Museum will portray colony's early days', Saturday Evening Mercury, 25 August 1956, p. 27.

51 Rowntree to Chairman Trustees, Vaucluse House, 31 May 1955, Correspondence Folder, Museums Other than Narryna, Narryna Heritage Museum; Joan Gillison, 'Narryna: Van Diemen's Land Folk Museum', Newspaper scrapbook, NHM.

52 Peter Mercer, 'Colonial pottery riches revealed', Mercury, 27 January 1990, p. 18; Petrow, 'In memory of ships', p. 35.

53 Crowther to Miller, 5 June 1964, PCS 1/529/308, AOT.

54 Mercury, 1 June 1981, p. 2; David Hinley, 'Magnificent obsession', Saturday Evening Mercury, 13 June 1981, pp. 30–1.

55 Carolyn von Oppeln, 'Sir William Crowther: A biographical sketch' in Gillian Winter (ed.), Tasmanian Insights: Essays in Honour of Geoffrey Thomas Stilwell, State Library of Tasmania, Hobart, 1992, pp. 219–21.

56 VDLMFM, Trustee meeting minutes, 12 August 1964, NHM.

57 Hinley, 'Magnificent obsession', pp. 30–1; Tape Number 37, 17 April 1989, p. 252, Geoffrey Thomas Stilwell AM: Oral History Project 1989. Interviewed by Joan Buckie, Non State 1436/25, AOT; Tony Marshall, '"The choosing of a proper hobby": Sir William Crowther and his library', Australian Library Journal, vol. 56, nos 3–4, 2007, 405–17 (pp. 406–7).

58 Stilwell interview, p. 252.

59 von Oppeln, 'Sir William Crowther', p. 224.

60 Marshall, '"The choosing of a proper hobby"', p. 410.

62 von Oppeln, 'Sir William Crowther', p. 213.

63 Davidson, 'Tasmanian Gothic', p. 311, found a photograph of Tasmanian Aborigines sitting 'reproachfully on a shelf in a back room [of Narryna]'.

64 Mercury, 29 June 1955, p. 11, 11 June 1959, p. 17; VDLMFM, Trustee meeting minutes, 8 August 1962, NHM.

65 Rowntree to Chairman Trustees, Vaucluse House, 31 May 1955, Rowntree to Alex Morrison, Secretary Board of Trustees, Newstead House, 17 August 1955, Correspondence Folder, Museums Other than Narryna, NHM.

66 Schmude to Rowntree, 16 June 1955, Correspondence Folder, Museums Other than Narryna, NHM.

67 Age, 18 August 1956, Literary Supplement, p. 20, Correspondence Folder, Museums Other than Narryna, NHM.

68 VDLMFM, Executive Committee Minutes, 24 July 1956, NHM.

69 ibid., 21 August 1956.

70 ibid., 1 October 1956.

71 Joan Gillison, 'Narryna: Van Diemen's Land Folk Museum', Newspaper scrapbook, NHM; Saturday Evening Mercury, 14 May 1955, p. 19.

72 Mercury, 16 June 1955, p. 20.

74 ibid.

Crowther to Miller, 5 June 1964, PCS 1/529/308, AOT.

75 Saturday Evening Mercury, 14 May 1955, p. 19.

76 Tasmanian Countrywoman, June 1955, p. 20.

77 Van Diemen's Land Memorial Folk Museum, The Trustees, Hobart, 1957.

78 Crowther to Mackaness, 6 May, 18 May 1957, Mackaness correspondence and literary manuscripts, MS534/178/166, National Library of Australia, Canberra (hereafter NLA).

79 Gwen Cox, 'Links with other days', Saturday Evening Mercury, 4 May 1957, pp. 4, 8.

80 Mercury, 15 May 1957, pp. 20–1.

81 Gwen Cox, 'A colonial treasure house', Air Travel, May 1957, pp. 3–6.

82 Mercury, 8 June 1957, p. 17.

83 Crowther to Mackaness, 18 May 1957, Mackaness correspondence and literary manuscripts, MS534/178/166, NLA.

84 Van Diemen's Land Memorial Folk Museum, The Trustees, Hobart, 1957; for the great stress laid on the educational aims see Rowntree to Chief Secretary, 24 January 1957, PCS1/352/308, AOT.

85 Crowther to Mackaness, 4 November 1957, Mackaness correspondence and literary manuscripts, MS534/178/182, NLA; Mercury, 3 December 1957, p. 5.

86 Mercury, 3 December 1957, p. 5.

87 Memo. by Bryden, 25 November 1971, Narryna Folder, vol. 1 1961–1971, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (hereafter TMAG).

88 Women were typically neglected in historical homes: see Marilyn Lake, 'Historical homes', Australian Historical Studies, vol. 24, no. 96, 1991, 46–54; also Linda Young, 'A woman's place is in the house museum: Interpreting women's histories in house museums', Open Museum Journal, vol. 5, 2002, http://hosting.collectionsaustralia.net/omj/vol5/young.html.

89 Mercury, 17 July 1958, p. 15, 24 September 1958, p. 18.

90 Mercury, 22 July 1958, p. 13.

91 Mercury, 19 August 1958, p. 13.

92 The Meredith collection was large enough for an exhibition to be held, see Annual Report of VDLMFM 1968–69, AA 494/1/808, AOT.

93 VDLMFM, Museum Committee minutes, 6 May 1959, NHM.

94 Mercer, 'Colonial pottery riches revealed', p. 18; Mercury, 17 November 2007, Magazine section, p. 20; from August 1957 details of gifts and donors were recorded and each gift was given a number, VDLMFM, Executive Committee minutes, 29 August 1957, NHM; Annual Report of VDLMFM 1968–69, AA 494/1/808, AOT.

95

Mercury, 4 September 1959, p. 13.

96

Sunday Tasmanian, 7 October 1984, p. 31.

97

Mercury, 3 September 2001, p. 10.

98 VDLMFM, Museum Committee minutes, 6 May 1959, NHM.'

99Hobart's historical folk museum' by 'Elizabeth', about 1963, Newspaper scrapbook, NHM; Annual Report of VDLMFM 1960–61, PCS1/455/308, AOT.

100

Mercury, 18 August 1964, p. 12.

101

Examiner, 28 July 1966, p. 19; see also a similar exhibition in 1990, Jean Panton, 'A new exhibition at Narryna Folk Museum: Glimpses of colonial childhood', Newsletter of the Museums Association of Australia, Tasmanian Branch, no. 27, 1990, 7–8.

102

Bay-City Star, 23 November 1995, p. 1.

103 Joan Gillison, 'Narryna: Van Diemen's Land Folk Museum', Newspaper scrapbook, NHM.

104

Sunday Tasmanian, 7 October 1984, p. 31.

105

Mercury, 22 November 1969, p. 8.

106

Mercury, 17 October 1979, p. 29.

107 The museum received 'a very large and comprehensive collection of needlework and clothing' from the estate of Mrs. FM Parker, Annual Report of VDLMFM, 1965–66, AA 494/1/808, AOT.

108

Mercury, 22 March 1995, p. 7.

109 VDLMFM, Museum Committee reports, 14 November 1972, NHM.

110

Mercury, 27 December 2001, p. 25.

111 Annual Report of VDLMFM 1960–61, PCS1/455/308, AOT; Mercury, 21 September 1960, p. 19.

112 Annual Report of VDLMFM 1960–61, PCS1/455/308, AOT.

113 Mercer, 'Colonial pottery riches revealed', p. 18.

114 'Elizabeth', 'Hobart's historical folk museum' about 1963, Newspaper scrapbook, NHM; around 1979 the Shiplovers Society moved to Secheron House and their room was converted into a Day Nursery, Annual Report of VDLMFM 1979–80, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

115 Newspaper scrapbook, NHM.

116 VDLMFM, Museum Committee minutes, 1 October 1958, NHM; Annual Report of VDLMFM 1965–66, AA 494/1/808, AOT.

117 Annual Report of VDLMFM 1960–61, PCS1/455/308, AOT.

118

Mercury, 4 September 1959, p. 13.

119 'Wayfarer', 'Folk museum shows how early farmers worked', Mercury, 27 September 1960, p. 10.

120 Annual Report of VDLMFM 1960–61, PCS1/455/308, AOT.

122 Submission of Dr William Bryden to Pigott inquiry, 5 September 1974, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

123 Special report on aims, achievements and attendance 1979–80, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

124 Brown to Acting Director, Tasmanian Arts Advisory Board, 14 February 1983, Narryna Folder, vol. 3, 1980–, TMAG; for examples of research using the Narryna collection see two books by Marion Fletcher: Costume in Australia 1788–1901, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1984, p. 98 and Needlework in Australia: A History of the Development of Embroidery, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989, pp. 15, 59 and plates 3 and 25.

125 Samuel JMM Alberti, 'Objects and the museum', Isis: Journal of the History of Science in Society, vol. 96, 2005, 559–71 (pp. 561, 569).

126 Peter Stone, 'A marriage of convenience? Heritage and tourism working together', Historic Environment, vol. 19, no. 2, 2006, 9–12 (p. 10).

127 'Elizabeth', 'Hobart's historical folk museum'.

128 Pat Weetman, 'For dear Papa, forget me not, 1842', New Idea, 16 April 1966, p. 14.

129 Mercury, 29 April 1959, p. 17.

130 Mercury, 26 June 1961, p. 8.

131 Annual Report of VDLMFM 1979–80, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

132 Alberti, 'Objects and the museum', p. 569; Sharon Macdonald, 'Accessing audiences: Visiting visitor books', Museum and Society, vol. 3, no. 3, 2005, 119–36 (p. 119).

133 Tamar Katriel, Performing the Past: A Study of Israeli Settlement Museums, Lawrence Eribaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, 1997, p. 71.

134 Macdonald, 'Accessing audiences', p. 131.

135 Visitor Book 1958 to 1961, 1 and 2 March 1958, 28 June 1958, 4 October 1958, NHM.

ibid., 8 and 9 January 1959.

136 ibid., 9 September 1959.

137 138 ibid., 24 January 1959.

139 Visitor Book 1989 to 1992, 16 February 1992, and Visitor Book 1996 to 1997, 10 April 1996, NHM.

140 Visitor Book 1958 to 1961, 24 September 1958, 8 and 9 September 1959 and Visitor Book 2000 to 2005, 24 March 2000, 6 October 2000, 12 June 2002, NHM.

141 Visitor Book 1983 to 1985, 26 November 1983, NHM.

142 For example see Visitor Book 2000 to 2005, 3 January 2005, NHM.

143 Susan Crane, 'Memory, distortion, and history in the museum' in Bettina Messias Carbonell (ed.), Museum Studies: An Anthology of Contexts, Blackwell Publishing, Malden, 2004, p. 321.

144 Newspaper scrapbook, NHM; Mercury, 25 May 1983, p. 21.

145 Visitor Book 1958 to 1961, 20 August 1960, NHM.

146 Visitor Book, 2005 to 2007, 29 March 2005, NHM.

147 Visitor Book 1977 to 1978, 17 January 1978, NHM.

148 Submission of Dr William Bryden to Pigott Enquiry, 5 September 1974, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

149 Mercury, 22 May 1968, p. 4.

150 Mercury, 16 March 1963, p. 6.

152 Report to the Trustees of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery on The Van Diemen's Land Folk Museum by Peter Mercer, 25 February 1983, Other reports and annual reports folder, NHM.

153 ibid.

154 ibid.

155 ibid.

156 ibid; Kavanagh, History Curatorship, pp. 45–49, 56.

157 Personal communication from Peter Mercer to the author, 7 August 2009.

158 Bill Neilson, 'Wealth of history too good to miss', Mercury, 6 August 1984, p. 2.

159 VDLMFM, Museum Committee minutes, 2 September, 14 October 1964, NHM; Annual Report of TMAG 1969–79, Typescript Annual Reports, TMAG; Clem Lloyd & Peter Sekuless, Australia's National Collections, Cassell, North Ryde, 1980, p. 207.

160 VDLMFM, Museum Committee minutes, 7 April 1965, NHM.

161 Mercury, 4 September 1959, p. 13.

162 Glenda King to Naomi Canning, 10 March 1989, Queen Victoria Museum Folder, NHM.

163 Thomas J Schlereth, 'Collecting ideas and artifacts: Common problems of history museums and history texts', in Carbonell, Museum Studies, pp. 335–42.

164 Thomas A Woods, 'Getting beyond the criticism of history museums: A model for interpretation', Public Historian, vol. 12, no. 3, 1990, 76–90 (p. 79).

165 Bennett, Birth of the Museum, p. 156.

166 ibid.

167 David Lowenthal, 'Pioneer museums', in Leon & Rosenzweig, History Museums in the United States, p. 120.

168 David E Kyvig, 'Foreword', in Levin, Defining Memory, p. 2.