When people think about 'traditional' museums, they often think first of natural history museums, founded in the nineteenth century at the height of a fashion for collecting. Thus the 'traditional museum display' is often regarded as a cabinet of specimens — dead animals or pressed plants — laid out to illustrate scientific principles. In some cases, it is enough for specimens to be 'curious', and therefore entertaining. Cabinets of curiosities have been important both in museums and in private houses, particularly in the Victorian era when many of Australia's colonial museums were founded. At the heart of these museums was their collection of stuffed and preserved animals — scientific specimens filled cabinets and drawers and drove museums' scientific research programs.

In the classic natural history museum, dead animals were used to exemplify various orders of nature. Sometimes the rule was rarity: animals entertained visitors with their 'strangeness', particularly in the original cabinets of curiosities. Sometimes biogeographical specificity provided an order: animals were grouped together because they came from particular continents or from a common environment-type (deserts, savanna-woodlands or polar regions). Most often, museum galleries used evolutionary or morphological principles to order their collections. All the primates or all the ungulates were grouped together, irrespective of where they lived. In the twenty-first century, when many museums aspire to display more than just natural history, the role of such collections is changing. Taxidermy specimens are often still seen as defining objects in museums, whether they entertain or advance science.

Taxidermy has shifted. It is no longer an art in the service of science; rather it is the backbone of art itself, both in and beyond museums. A new twenty-first century school of art dramatically depends on the museum animals embodied in it. Animals taken originally for scientific purposes have, two centuries later, become part of an art movement that speaks to a new ethics for non-human others. This paper considers these specimens a hundred years (or more) after they were collected, as they become enlisted in the service of different work, inside and outside the institutions that have preserved them. The transition of taxidermy specimen objects out of natural history and into art installation sheds light on the changing nature of museums. It also suggests that new ideas are emerging about the ethical responsibilities of people towards animals.

____________________________________________________

by Janet Laurence

Museum Victoria

a glimpse into the collection objects have seemingly escaped from their adjacent storage [but] have been selected not on museum principles but by attraction, through reverence and empathy.[1]Laurence was shaking off the dust of the museum's order for nature, disrupting it by asking cultural questions about these natural objects. She designed a cabinet where the birds, beetles and other natural history objects challenged and unsettled assumptions about the way people and animals interact, and which attacked, in a sense, the museum's original raison d'être.

As is the case with all museum exhibitions, what visitors made of this artistic science or scientific art was influenced by where they had been before, and what they were expecting to see. The artwork became a monument to an intriguing historical moment. It was designed for a new building to showcase the collections of the multiple former museums of Victoria.[2] As Ian McShane comments, 'The opening of the Melbourne Museum in 2000 marked the end of a period in which the thematics, locations and corporate arrangements of Victoria's nineteenth-century state museums were thoroughly overhauled'.[3] Within Denton Corker Marshall's award-winning new building, galleries of history jostle with natural history. Different designers produced galleries of Aboriginal history, settler history, natural history and technology.[4] A huge Forest Gallery (initially known as the Gallery of Life) comprised living trees with real birds flying around their canopies. This marked a significant departure from the nineteenth century cabinets of curiosities in the old natural history museum. In a museum with multiple galleries, each with different curators and independent designers, the challenge of explaining to the public what the museum was about was given to Laurence. She was commissioned to create a conversation piece that said something about the museum as a whole. The artwork was installed as a feature of what architects call the 'upper level circulation spine', a designer- and curator-free space between galleries.

According to critic Paul Walker in Architecture Australia in January 2001, Stilled Lives 'skilfully negotiate[d] the complexities of the contemporary museum'. From his perspective, visitors were 'enjoying the decontextualised and ordered things in Janet Laurence's vitrines'.[5] Walker's language is obscure. What does it mean for something to be both decontextualised and ordered? Perhaps Walker himself was seeking a 'new order', to make sense of dissonances between very disjunct galleries, and was trying to conceptualise a whole museum that was more than the sum of its parts. In any case, this is what he hoped the visitors found in Stilled Lives.

There is no evidence that Walker had discussed his perceptions of visitor behaviour with museum staff. At least some visitors were certainly aware of the decontextualisation, and were discomfited by it. According to historian Tom Griffiths, who consulted museum staff working in the adjacent Forest Gallery, visitors were frustrated by Stilled Lives. A cabinet like this aroused curiosity, but also left it unsatisfied. This was not how a museum should work, they felt. There were no labels in Laurence's artwork, but there was text: 'disembodied, single words, uncapitalised, that drift in ghostly font among the specimens', as Griffiths puts it.[6] The words were not the nouns of information visitors expected and wanted; they were, rather, the verbs of actions performed on the dead animals: 'fetishised; possessed; celebrated; collected; salvaged ' It was a dislocating experience for visitors who moved from the Forest Gallery (where there are clear, conventional natural history labels), to confront the Stilled Lives cabinet of animals and disturbing verbs. Here were animals that were 'flamboyantly dead', in Griffiths' words. They broke the rules of (natural history) museum expectations. This was particularly evident to visitors coming out of the Forest Gallery. Perhaps only those concerned with overall architectural design, like Paul Walker, could attribute 'order' to this installation where art and science rubbed together awkwardly — undoubtedly Laurence's intention.

The dead animals were displayed to make visitors reflect on and engage with the museum, its collections and purposes, but perhaps also to question the deaths. Janet Laurence suggested that they should make visitors think about the animals themselves, and the way people relate to them. The verbs in the cabinet were important too.

This ordering of nature preceded the British settlement of Australia and New Zealand, but Linnaeus's ideas were influential in British scientific thinking and aroused curiosity in new nature, in animals that challenged the categories of Linnean order. Australia was conceived of as a place of 'exceptional nature', 'antipodean', with 'all things queer and opposite' — that was threatening to the existing order.[8]

Museum cabinets developed for two purposes, at times at odds with each other: science and entertainment. The animals in them were both scientific reference specimens and wondrous and entertaining. Natural history museums were more explicitly educative than zoological gardens, which were generally entertaining pleasure gardens for fair weather. Museums were weather-proof, and offered serious entertainment, more than just an outing. Specimens of animals in ordered rows (like butterflies) or in cabinets of like 'classes' (felines, primates, ungulates, etc.) extolled not only the variety of the animal world, but also its fundamental order.

In the centuries of Western expansion and exploration, museums brought the wonders of the world to the ordinary citizen, to underscore the advantages of empire. Entertainment and curiosity were entwined in cabinets of the objects of empire, along with the commercial opportunities of such 'resources'.

The geography of the world became increasingly a matter of knowledge and less of myth. Cabinets also came to inform visitors about the geography of places, and parallels between species that lived in like places, under the influence of the ideas of Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859). Humboldt was the founder of the discipline of biogeography, the science that unites ecology and geology. According to Charles Darwin he was 'the greatest travelling scientist who ever lived'. Museum cabinets increasingly displayed biogeographic order in the later nineteenth century, particularly influenced by Alfred Russel Wallace, another great traveller, who ordered the animals of the world on biogeographical principles. Wallace's Line, running between Bali and Lombok, defined a new Australasian biogeographical region beyond the 'south-eastern limits' of the Indian region, thus creating a special category of particular interest to Australian museums:

I draw [the limit] between the islands of Bali and Lombok, and between the Celebes and Borneo, and the Moluccas and the Philippines. Barbets reach Bali, but not Lombok; Cacatua [cockatoos] and Tropidorhynchus [friarbirds] reach Lombok, but not Bali: this I think settles the point.[9]When Wallace published his paper in Ibis in 1859, colonial museums were new and few, but the numbers were growing, and natural history was important to all of them.[10]

Taxidermic art was appreciated beyond public museums. Private collectors displayed taxidermic specimens in their sitting rooms, sometimes in private cabinets of curiosities, or in the case of birds, often on a 'tree' in a cabinet, with wings spread or heads thrown back in song. Most common of all was a large animal head on a wall, preferably with horns, antlers or tusks, mounted on a board. The plaque on the board celebrated the hunter and his achievement, and sometimes the place and date of the hunt, and occasionally the scientific name of the animal. The bigger and wilder the head, the greater the hunter. Historic taxidermic specimens from the Victorian era continue to be private collector's items, but in the present era are more often displayed ironically.[12] In a chic café in Copenhagen there is a polar bear dressed in a dinner suit. It is actually an art installation hybrid, comprising a polar bear's head and a human body, but it hovers like a waiter. A deer sporting elegant leather gloves supervises the same café's website. Such features not only add to the retro café atmosphere, but are also art pieces based on taxonomic specimens purchased in antique markets.[13]

The artistry of taxidermy has been appreciated in all eras, but in different ways. In the public museums of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, cabinets of taxidermic natural history specimens sometimes represented the imperial glory of animals collected as resources. In an echo of the private hunting trophy, some natural history cabinets were established as a tribute to empire — and therefore favoured bigger, odder, more exotic animals. For example, the traditional natural history galleries of the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, reflected on the glory of King Leopold II, and his empire in Congo. The Africa Museum was built at Leopold's estate at Tervuren (in the outer districts of Brussels) between 1904 and 1909, as part of his vision for a smaller Versailles. The museum was complemented by Chinese and Japanese pavilions, a World School, Congress Centre, French gardens, and other references to the French cultural mecca.[14] The ethnographic and natural history collections were largely assembled during the periods of the Congo Free State (1885–1908) and the Belgian Congo (1908–60).[15] The idea of a display area for information about the natural history of animals was only a secondary consideration when the museum opened its doors in 1905.

In the twentieth century, as the science of ecology grew, the focus shifted from the ordering and classification of dead specimens to studying the animal's living behaviour and adaptation to different environments. Museums responded by expanding their cabinets to include a new 'environmental' context for the taxidermic animals through dioramas. A three-dimensional environmental surround was added to lifelike animals with a picturesque backdrop, painted to give depth to the specimens along with other 'foreground' elements such as rocks and plant material. Real animals stuffed to live again were placed on a habitat stage-set. The cabinet became a theatre, and the pose of the animals told a scientific story. The American Natural History Museum in New York boasted particular mastery of the diorama, the art piece with a scientific message. These are now 'heritage items' and still a point of pride. According to the museum's chairman:

The habitat dioramas are among the greatest treasures of the American Museum of Natural History, Perhaps nothing embodies the spirit and mission of the Museum as completely as these amazing technical feats of illusion, which are recognized internationally as superb examples of the fusion of art and science.[16]The illusion of the background artwork is crucial, but so is the taxidermic artistry of the animals, crouched ready to pounce. Without real animals, the diorama would be informative, but the entertainment comes from the sense of action.

In a stimulating paper, Karen Wonders, a Canadian artist and historian of science, reviews the diorama tradition in Swiss, German, Scandinavian and Hungarian natural history museums, and argues that the 'theatre' can be pushed further to press environmental consciousness. In the Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum in Hannover, Germany, for example, a series of dioramas featuring farm animals illustrate 'the destruction of an ecosystem': the background shifts from a forest farmhouse, to a more open farm and finally to an industrial farm with a paved road and no trees. The sequence of dioramas illustrates the intersection between modernity and primary industry in the region. Wonders shows how diorama art has the potential to elucidate not just the scientific specimens, but also their trajectory in history.[17] Like a repeat photographic sequence, the dioramas can cumulatively work to tell a story.

Buggy rug made of thylacine skins, about 1903

thread wool baize, metal (copper alloy), 108.2 x 118 cm

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, presented by the Federal Group, 2002

Endling

In 1999 there was a request to purchase a thylacine skin for the National Historical Collection of the National Museum of Australia. It came from curators of one of the permanent galleries in the new museum. The exhibition module, entitled 'Endling', was to be about the idea of extinction. Acquiring this object was controversial. Was 'extinction' a suitable subject for a social history museum? And could an animal skin be part of Australia's National Historical Collection?

It was evident that the extinction of the thylacine was a cultural — not a natural — event, and very much part of the history of European settlement in Tasmania. But the skin itself needed a history. Eventually the acquisition was approved by shifting the emphasis away from the animal to the hunter. Today, the skin is being rested for conservation purposes, but you can still find in a corner of the 'Endling' cabinet the story of Charles Selby Wilson, the man who snared the last wild thylacine in 1930[18] . An 'endling' is the last animal of its species. The trope of the 'last wild animal' was important to both the purchase and the exhibition of this skin. The animal was trapped at a time (1930) and in a place (Pieman River, north-western Tasmania) when it was certainly one of the last. The fact that the skin could have belonged to the last wild animal justified its purchase — but the fact that the skin had a social history as a commodity was the deciding factor. Although it is no longer on show, the old-fashioned story of the hunter remains important to making sense of the extinction cabinet. For some visitors, the story may seem anachronous in a museum built in an era when hunting trophies are more often turned into retro café furniture — they see in such a trophy the masculinity of the hunting tradition, not the animal's story[19] — but in this exhibit, the story the museum set out to tell was about changing attitudes to nature and the shifting social value of the skin: first as a trophy, later a symbol of Tasmania (where it was exhibited at the opening of the new Cascade Brewery), then as a symbol of extinction and the memorialisation of loss.[20]

But the real issue was that without this social history a thylacine skin was just a dead animal, not an inherently cultural object suitable for a National Historical Collection. It had been tanned, but that was all. It was not something 'culturally constructed' or with a social purpose, like the buggy rug comprising eight thylacine skins stitched together that was recently purchased for the collections of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, and the Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston, in Tasmania. The National Historical Collection has possum, rabbit and even platypus skin cloaks and rugs.[21] But a skin without an intrinsic social purpose was otherwise dangerously close to being constructed by visitors as 'just a hunting trophy'.

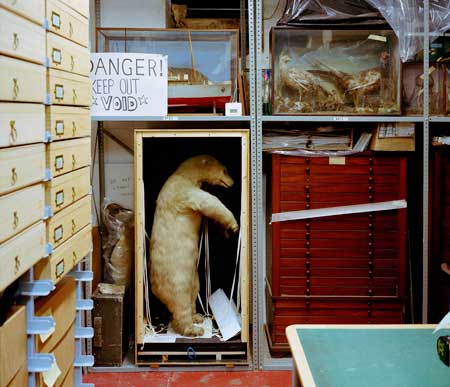

Snæbjörnsdóttir's and Wilson's travelling exhibition moved through a series of museums and art galleries between 2006 and 2009, exploring the space between 'museum' and 'art'. In Leicester at the New Walk Museum & Art Gallery, it showed in 2009 as Nanoq: Flat Out and Bluesome, the title of the book that accompanied the show. The book includes reflective essays by academics Steve Baker and Garry Marvin with titles such as 'What can dead bodies do?' and 'Perpetuating polar bears: The cultural life of dead animals'.[23]

Nanoq is at the leading edge of a new art movement that challenges the place of animals and their bodies in museums. It charts 'the uneasy relationship between the wild and its representation in our museums, galleries and media [and] highlights the current plight of polar bears who are facing extinction because of the destruction of their habitat'.[24] These bears are no longer objects, performing realistic animal activities in dusty dioramas, but rather particular bears from particular places at the time of their death, and in other particular places at the time of being photographed.

The current situations of the polar bears, according to the explanatory caption, range 'from cluttered natural history displays' in museums through to the 'measured grand arrangements of colonial artifacts in stately homes'. Perhaps most poignant of all was the bear photographed wrapped in plastic, forgotten in the back room of a museum, deep in storage. This was a reminder of how politics can change and marginalise even the most significant items. As the photographers comment in the main storyboard for the exhibition:

The display of these animals in such a variety of ways leaves us caught in limbo. Clearly we are confused as to what to do with the legacy It is no longer possible to see the bear as an animal in the way perhaps we might have done before moving pictures and sumptuous wildlife documentaries.

The display of these photographs in the Fram Museum, a polar exploration museum, proved another challenge. The Fram is an A-framed building, purpose-built on Oslo harbour to house the Fram, Roald Amundsen's ship made famous by the heroic South Pole Expedition of 1910–12. The Fram also explored the North Pole, home of the polar bear, and the North Pole context is symbolised by an old-fashioned display of a polar bear family. In fact, visitors to Nanoq turn from the upper gallery of the museum to confront a family group of taxidermic polar bears, two adults and two young bears, that are in an imitation ice cave in the narrow entrance to the museum itself. These bears are real, not photographed, on permanent display and without a caption, even a temporary one, to link them to Nanoq. This is a shock after the Nanoq photographs, where each bear had its own biographical caption. For me, the anonymous bears affronted the new sensibilities aroused by the exhibition — and perhaps that was the intention.

In Picturing the Beast: Animals, Identity and Representation, Steve Baker uses animals as a way to think about humans, rather than the other way round. He does not construct a history of the treatment of animals but, rather, he looks at how animals are pictured by those who do not usually reflect on their relations with animals. Consideration of how a society unconsciously treats its animals is a way to unravel that society's mentalité. A new ethic of human–animal relations depends on more than logical arguments about animal rights; it also depends on noticing the unconscious, inadvertent treatment of animals that human society tolerates, he argues.[26]

New York artist Mark Dion's 1996 installation, Tar and Feathers, is a case in point. Dion uses a real tree, with a variety of taxidermic animals, birds and reptiles strung up in its branches. Both tree and creatures are dipped in tar. Dion, born in 1961, comments on his work:

You can sense that it has a pretty dark tone. As much as I'm engaged in a discourse that is ecological, I'm not one of those artists who is spending a lot of time imagining a better ecological future. I'm more the kind of artist who is holding up a mirror to the present and to the kinds of problems that we have right now. As much as I would like to have a more utopian sensibility, my sensibility tends to the dystopian, to the dark side.[27]

His art is focused on the humanity revealed by the animals while at the same time treating them as material subjects for his art. But what about when we travel beyond art and museums?

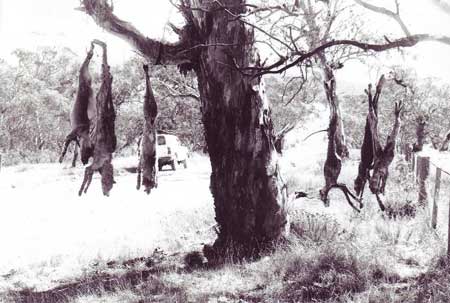

In 2004 historian Darrell Lewis photographed a tree hung with dead feral cats at William Creek on the Oodnadatta track in desert South Australia. In front of the tree is a handprinted sign, 'Pussy Willow (Acacia felinata)'[28] . It is a mausoleum, not a museum. Lewis's dog, Kelly, plays in the foreground, a touch of humour in a grim scene. To echo Dion's words, such an Australian vernacular landscape has a 'pretty dark tone'. What sort of society is mirrored in this Australian backyard?

Lewis found another such tree later the same year: the dingo tree of Lake Eucumbene, in the high country near Adaminaby near Canberra. If the desert tree is Acacia felinata perhaps we should call this one Eucalyptus caninatus. This tree is about an economy 'red in tooth and claw'. In an echo of Victorian England, the wild dogs/dingoes are hung like criminals, then skinned for their hides. Someone has hung, drawn and quartered these animals, obstacles to sheep-farming in this district.

Feral cats and wild dogs are animals that feed on other animals: they live and die in relation to animals as well as humans. The carcases throw up questions of what it means to be feral in the Australian landscape in the era of invasive species biology. Can conservation biology create a new moral status for biologically invasive animals? What does it mean for Australia to lead the world in mammalian extinctions — and what should be done about it? And should the same rules apply to the economy as to the ecology? Does a consciousness of damage justify killing the perceived perpetrators? Perhaps.

But the trees are more than dead animals, more than science or art. They are dramatic statements of human–animal relations. When the 'wicked' animals are dead, why should they also be strung up, skinned? Are they supposed to be a warning to other wild cats and dogs just as the hanged criminal was once considered a warning to criminal elements in Victorian society? Or are they symbolic of a new hunting heroic, something acceptable in a world where the taking of polar bears is no longer so?

Like the artist who holds up a mirror to the present and to the kinds of problems that we have right now, the creators of trees like this — dystopian landscape features — force us as viewers to think about what is humane and ecological in the pastoral landscapes they adorn. Dead animal trees confront their viewers to think about both the animals and the perpetrators of the exhibits. They provide a commentary of sorts on the continuing controversies in the history of human–animal relations.[29]

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

2 Carolyn Rasmussen (with 46 contributors), A Museum for the People: A History of Museum Victoria and its Predecessors, 1854–2000, Scribe, Carlton, 2001. The predecessors included the National Museum of Victoria, and the Museum of Natural History and Economic Geology, which was the original manifestation in 1854.

3 Ian McShane, 'Melbourne Museum', in Chris Healy & Andrea Witcomb (eds), South Pacific Museums: Experiments in Culture, Monash University e-press, Melbourne, 2006, p. 7.1.

4 The galleries were designed to complement the resources of Scienceworks, the museum of 'hands-on' science material, housed since 1992 at the old pumping station at Spotswood, 5 kilometres away from the CBD.

5 Paul Walker, 'Melbourne Museum: Denton Corker Marshall skilfully negotiate the complexities of the contemporary museum', Architecture Australia, January–February 2001, www.archmedia.com.au/aa/aaissue.php?issueid=200101&article=9&typeon=2, accessed 28 February 2009.

6 Tom Griffiths, 'The gallery of life', Meanjin, vol. 60, no. 4, 2001, 85–92 (p. 87).

7 Carl Linnaeus, Caroli Linnaei Systema Naturae (1735). Taxonomic editions: Genera Plantarum (5th edn, 1753); Regnum Animale (10th edn, 1758).

8 'All things queer and opposite' is the motto written in 1839 in the minute book of the Tasmanian Society, which was one of Australia's earliest natural history societies (Kathryn Medlock, pers. comm.). Its Latin translation (Quocunque aspicias hic paradoxus erit) appears on a ribbon around another dead animal, a flattened platypus skin, on the title page of the Tasmanian Journal from 1842. On antipodean thinking, see also George Seddon, The Old Country, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2005; Libby Robin, How a Continent Created a Nation, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2007, p. 32.

9 Alfred Wallace, 'Letter from Mr. Wallace concerning the geographical distribution of birds', Ibis, vol. 1, no. 4, 1859, p. 450. Tropidorhynchus later became Philemon (friarbirds, a genus of honeyeaters).

10 The Australian Museum was founded in Sydney in 1827, the (National) Museum of Victoria in 1854, the Queensland Museum in 1861, the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (Hobart) in 1862 and the South Australian Museum the same year. The Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery Launceston was founded in 1891 (but the collections of the Launceston Mechanics Institute date back to the 1840s) as was the Western Australian Museum (Perth Museum).

11 Paul Farber's Discovering Birds: The Emergence of Ornithology as a Scientific Discipline 1760–1850 (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1997 (first published 1982)) is an excellent source of information on the changes in quality of bird specimens resulting from arsenic treatment.

12 Terry Trucco, 'Stuffed Victorian birds and beasts are on the prowl again', Thursday, June 20, 1991, http://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/20/garden/stuffed-victorian-birds-and-beasts-are-on-the-prowl-again.html?sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all, accessed 21 March 2009.

13 Bankeråt, Nansensgade, Copenhagen, pers. obs. 2008; www.bankeraat.dk/ombankeraat.html, accessed 21 March 2009.

14 Royal Museum for Central Africa website, www.africamuseum.be/museum/about/histobuildings/museum/about/ histobuildings/histomuseum, accessed 5 April 2009.

15 Personal observation, July 2007. Many of these have been dismantled and renovated in recent years.

17 Karen Wonders, 'Habitat dioramas as ecological theatre', European Review, vol. 1, no. 3, 1993, 285–300. I am grateful to the author for supplying this paper to me.

18 http://www.nma.gov.au/collections/slideshow_2_3.html, accessed 26 March 2009.

19 Karen Wonders, 'Hunting narratives of the Age of Empire: A gender reading of their iconography', Environment and History, vol. 11, 2005, 269–91.

20 MA Smith, 'Endling', in Land Nation People: Stories from the National Museum of Australia, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2004, p. 100.

21 Gunditjmara possum skin cloak (Object 2003.0028.0002), www.nma.gov.au/collections-search/display?irn=70470; Bedcover made in 1938 from 54 rectangular sections of tanned rabbit pelts (Object 1986.0129.0001), www.nma.gov.au/collections-search/display?irn=34356.

22 See the 'Leicester museums and galleries' page on the Leicester City Council website, www.leicester.gov.uk/your-council--services/lc/leicester-city-museums/exhibitions/nanoq, accessed 21 March 2009.

23 Bryndis Snæbjörnsdóttir & Mark Wilson (eds), Nanoq: Flatout and Bluesome: The Cultural Life of Polar Bears, Black Dog Publishing, London, 2006.

24 'Leicester museums and galleries' website (accessed 21 March 2009), and personal notes.

25 Troy Emery, 'The aesthetics of taxidermy in contemporary art', paper presented at The Antipodean Animal conference, Kings College, London (organised by Ian Henderson), July 2008. See www.kcl.ac.uk/content/1/c6/03/56/10/PROGRAMMEAntipodeanAnimalJul082.pdf, accessed 5 April 2009.

26 Steve Baker, Picturing the Beast: Animals, Identity and Representation, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1993, especially Chapter 1, 'From massacred cats to lucky cows: History and mentalités', pp. 3–32.

27 Dion quoted on the Terminartors website, http://www.terminartors.com/dion-mark/tar-and-feathers-1016860-p.

28 The sign is clearly visible in the online photograph at http://image12.webshots.com/13/1/68/34/138516834HLNwDK_fs.jpg, accessed 5 April 2009.

29 I would like to thank Darrell Lewis for sharing some of the photographs from his major personal collection of images of the Australian outback vernacular landscape, and stimulating discussions with him about the cat tree and the dingo tree over several years. I would also like to acknowledge Ian Henderson, Steve Baker, Deb Verhoeven and the other speakers at the conference on Antipodean Animals in London in July 2008, where many of these ideas began, and the helpful comments of anonymous referees and the editorial team at reCollections.