review by Mike Smith, 2009

Imagine a prosperous provincial town in middle Australia — perhaps like Dubbo or Wodonga. Its people are go-ahead, exuberant and cheerfully materialistic. They have an appetite for the latest Domayne or Harvey Norman homewares and for bright (almost garish) decor. Then imagine that this town is totally destroyed in a single day. Not just destroyed but entombed so effectively beneath 5 metres of volcanic ash and pumice that its location and geography are erased from the map. How would we tell the story of this doomed town? What stories would we choose to tell?

The exhibition A Day in Pompeii examines the Roman town of Pompeii. Most visitors will know at least the outline of the story. A small town of 10–12,000 people on the Bay of Naples was destroyed by the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius on 24 August 79 AD, along with the neighbouring towns of Oplontis and Herculaneum.

Rediscovered by antiquarians and treasure-hunters in the eighteenth century, Pompeii rapidly entered the European imagination. Bulwer-Lytton's 1834 novel The Last Days of Pompeii explored the decadence and immorality of first-century Rome, contrasting this with the older, more philosophical Greek culture and the more severe ethics of an emerging Christianity.[1] The 1935 RKO film, also called The Last Days of Pompeii, explored similar themes of sin and redemption, while EMI's Up Pompeii (1971) reduced the final days of the doomed town to a bawdy romp. All of these works positioned Pompeii as a 'Sodom and Gomorrah', blithely unaware of the retribution to come. For scholars, however, the excavation of Pompeii marked the rediscovery of classical antiquity and the beginnings of classical archaeology. The remarkable preservation of the town made its mark on archaeological thought: archaeologists have their 'Pompeii premise', the oft-challenged assumption that the archaeological record preserves a snapshot of past societies, somehow frozen in mid-stride.[2]

A Day in Pompeii follows the conventional storyline (stripped of its moralising), focusing on the last day of a doomed town. Let's walk through the exhibition and get a feel for it.

Outside the Museum and in the foyer, large murals of gladiators, volcanoes and cut-out figures of Roman tribunes catch the visitor's eye. Downstairs in the temporary exhibition gallery, the 'Atrium' provides entry to the exhibition as well as a potted history of Pompeii.

Visitors then move into a gallery exploring the life of the town. Like all the exhibits, these are extraordinarily rich in objects (anchors, amphorae, coins, medical instruments, cooking utensils and weapons) collectively portraying the town as a lively commercial hub. The re-creation of a shopping street, with its wine bars and takeaway food stalls, echoes the cafes of Lygon Street, a short stroll from the Melbourne Museum. A small exhibit on gladiators goes some way towards meeting the expectations raised by the Museum's marketing pitch, but visitors expecting massed gladiators and Roman legionaries will be disappointed.

The people of Pompeii are almost lost among the objects here. The clever use of street graffiti (translated from the original Latin or Oscan) counters this by providing a strong personal dimension. 'Atimetus got me pregnant', says one. Another chivvies us: 'Do not let bristly hair make your legs rough'. Some reflect the nouveau-riche provincialism of the town: 'Profit is happiness', and (my favourite): 'Don't be tiresome. Don't have your hairstyle done and undone. Leave your hairdresser in peace'. A soundscape reinforces the human presence, providing an overlay of Latin voices, as well as the everyday sounds of the waterfront. Ominously, we can hear the distant rumbles of Mount Vesuvius from a 3-D theatre deeper in the exhibition.

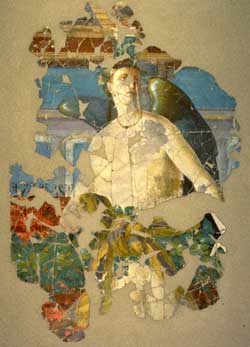

Visitors move from the public life of the town into the private life of the home. A series of exhibits show the rich decor, beautiful wall frescoes and sumptuous homewares of first-century Roman life. More graffiti sets the tone: 'Baths, wine and sex ruin our bodies, but what makes life worth living except baths, wine and sex?' You find yourself warming to Pompeiians. A text panel wistfully sums it up: 'Yes, for many Pompeiians, life was good'.

As the picture of a lusty, brash town is developed, visitors find themselves closer to the noise of a volcano erupting. Our route takes us into a 3-D theatre to see the horrifying sequence of destruction as an earthquake, then pumice, lapilli and ash-falls, and a torrent of super-heated gas, ash and rock wipe Pompeii from the face of the earth. The by-now rather chastened visitors leave the theatre to walk along a timeline providing extracts from the letters of Pliny the younger. Pliny left the only eye-witness account of the eruption and the first written description of a pyroclastic flow. A nearby exhibit on volcanology presents a history of Mount Vesuvius and explores the probability that another Plinian eruption will obliterate modern Naples.

Up to this point, the impact on the inhabitants of Pompeii has been appreciated only in the abstract. Then one arrives at the body-cast room. In this circular space are casts of eight people, a dog and a domestic pig. These are not actual bodies, of course, but plaster casts made from voids left in the ash as the bodies decayed, but the effect is intensely emotional. A guard dog on a chain climbs higher and higher to escape the accumulating ash until it dies in agony. A dying man reaches out to protect his wife. A shackled man — a slave or criminal — crawls to the gate of Pompeii before dying. A young woman uses her tunic to protect her face and dies face-down in the ash. This is a moment when we are confronted with the intimate human dimensions of the destruction of Pompeii. Only 2000 of the 12,000 inhabitants of the town are thought to have perished, but the immediacy of each death is shocking.

The remainder of the exhibition seems anti-climactic. Nevertheless, there is an excellent history of the rediscovery of Pompeii and of the various archaeological excavations there. A final theatrette, 'Postcards from Pompeii', presents a loop of images showing the ruins today, and there is the inevitable exit via a shop filled with faux-Roman merchandise. On a panel near the exit, the contributions of external advisors, sponsors and the designers are acknowledged. A Day in Pompeii is clearly the work of a talented team of curators, conservators and registration staff. It is disappointing, therefore, to see that the work of individual museum staff is not credited.

A Day in Pompeii is a sumptuous, highly professional exhibition with a dramatic storyline, well told. To have successfully brought the Pompeii collections to Australia represents a triumph of international negotiation on the part of Museum Victoria (of which the Melbourne Museum is a part), as well as a productive collaboration with the Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei (the Italian government body responsible for archaeological sites in the Pompeii region and for the National Archaeological Museum in Naples).

So how well does the exhibition work?

The most obvious problems are those of any 'blockbuster' exhibition. The layout is congested and does not cater for the large numbers of visitors expected at an exhibition of this stature. When will museums learn? Even with timed-entry tickets the exhibition was uncomfortably crowded by noon, making it difficult to get close to displays or to navigate between exhibits. Disabled access would be difficult. Labels and text mostly work well with the objects, but are too detailed to read easily amid the press of visitors. The crowding is compounded by a remarkably poor hierarchy of text panels: apart from the 'trail guide' brochure, way-finding is poor.

More successful are the interactive touch-screens positioned at strategic points throughout the exhibition. These allow visitors to take a virtual walk through a Pompeiian home or explore other aspects of Pompeii life. These were so popular with children that I couldn't get near most of them. Inexplicably, I had the last interactive — on the history of archaeology — entirely to myself!

Despite the lushness and Italianate palette of this exhibition, the design is predictable and rather passive. There is no innovative 'scenography', and little to challenge the viewer to think about Pompeii in new ways or set up a dialogue between design and object. The 3-D theatre and the body-cast room provide elements of drama and revelation but are driven by content not design.

Museum exhibitions are limited in the level, complexity and type of content they can effectively deliver. Even so, there were three areas where I felt the content was deficient.

First, this exhibition does not give visitors a sense of the structure and function of the town as a whole, or its role as a small provincial centre. The town is rather lost among the objects. The sheer diversity of beautiful objects almost make this an art exhibition and the designers have had to work hard, using faux streetscapes and facades of villas and colonnades, to keep a broader focus. However, the only town map is in the 'Atrium', which visitors sweep through to enter the exhibition. I thought the catalogue might answer my questions — What sort of town is this? How was it organised and laid out? — but found it simply reproduces the text panels and labels.

Second, there is little sense of 'a place in time'. Given that the general public may conflate dinosaurs, Romans, Vikings and Aztecs into a generalised 'past', museums need to do more to give visitors basic historical context and a visceral grasp of the passage of time. How many visitors would appreciate that the Roman world lasted for more than 900 years (from the beginning of the Roman Republic in 509 BC to the collapse of the western empire in 476 AD) and that Pompeii provides a window on one small town somewhere in the middle of this vast time period?

Third, A Day in Pompeii gives the impression that the people of Pompeii were just like us — simply a town like Dubbo or Wodonga transported back 2000 years. As human beings and as people with likes and loves this is no doubt true. But it also risks representing past societies as simply middle Australia with Italianate decor, ignoring fundamental differences in our societies and values. The richness and detail of the archaeological record from Pompeii should allow us to do better than this. In this regard, the focus on the destruction of Pompeii distracts from the opportunity to make the most of Pompeii as a time capsule of Roman society in the first century AD.

Mike Smith, an archaeologist and environmental historian, is a senior research fellow in the Centre for Historical Research, National Museum of Australia, and an adjunct professor in the Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra.

2 LR Binford, 'Behavioral archaeology and the "Pompeii Premise"', Journal of Anthropological Research, vol. 37, no. 3, 1981, 195–208.

| Exhibition: | A Day in Pompeii |

| Institution: | Melbourne Museum |

| Curatorial team: |

Eve Almond, project manager Phil Spinks, site manager Helen Privett, conservator Caroline Carter, collection management Rolf Grive, head technician Hayley Townsend, multimedia Kelly Grant, multimedia assistant |

| Design: | David Lancashire from David Lancashire Design |

| Venue/dates: | Melbourn Museum, Melbourne, Victoria, 26 June − 25 October 2009 |

Publication: | A Day in Pompeii, Museum Victoria, 2009, RRP A$19.95 |