Chinese skiers of Kiandra: Object and narrative

Introduction

The National Historical Collection of the National Museum of Australia contains a pair of wooden skis. Dating from about 1880, they are thought to have been made in Kiandra in the Snowy Mountains region of New South Wales and were owned by the Yen family of what is now referred to as ‘Old’ Adaminaby. In 1958, the skis were retrieved from the property of Geoff Yen in Old Adaminaby by architect and aesthetics advisor to the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Authority (SMHEA), Donald Maclurcan, just prior to the flooding of the town for the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. Maclurcan, who was also team manager for the 1960 Australian Olympic ski team in Squaw Valley, in the United States, donated the skis to the Museum in 1986.

photograph by Katie Green, National Museum of Australia

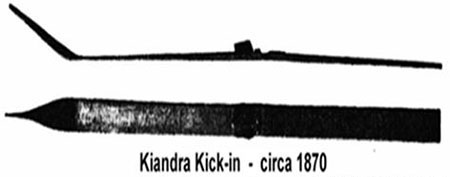

Made from alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis), one of the world’s tallest flowering plants, each ski measures more than two metres in length and has been hand-carved and shaped from a single length of seasoned timber. Originally called ‘butter pats’, referring to the pattern of grooves on the underside, the skis have turned-up tips and leather bindings to hold the feet securely in place.[1] Skis of this type, known as ‘Kiandra kick-ins’, were used during what is understood to be the world’s first International Snow Shoe Carnival in Australia in 1908.[2] They continued to be used until about the 1930s, when laminated skis (which had first appeared in 1891) and, later, aluminium, flexible plastic and fibreglass models became widely manufactured and used.[3]

To a casual observer, while their appearance is distinctive, these skis are conventional in most respects. However, this essay seeks to show that by unhitching them from the particularities of their manufacture and intrinsic purpose, these commonplace objects conceal an unexpected and complex narrative that ranges geographically – from Scandinavia to the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales; historically – from Australian goldfield history to the drowning and loss of the tiny village of Old Adaminaby; and culturally – from Chinese immigrant identity to complex contemporary concepts of what it means to be Australian.

Holmenkollen Ski Museum

Travelling on snow

The prehistoric development of forms of snow travel, such as webbed snowshoes and skis, was precipitated by climatic conditions in arctic regions of the world, which made such travel challenging. Snowshoes, which are still in use today, are a form of utilitarian footwear for short excursions into the snow, but are unsuitable for use in deep, powdery snow, or when speed is necessary.[4] Rather than sinking into snowdrifts with each step, skis made from long pieces of wood with a smooth undersurface are far more effective than snowshoes, enabling people to glide easily over the snow. Adjusting the length and width of skis allows them to be used by people of different weights.[5]

Snow travel in Australia

Following the discovery of gold at Kiandra in the Australian Alps in 1859, goldminers from many parts of the world converged on the area. While it is not certain who manufactured the first skis in Australia, records indicate that, in the summer of 1860, Norwegian miner and former ship’s carpenter, Elias Gottaas, together with fellow Norwegians Soren Torp and Carl Bjerknes, began manufacturing Norwegian-style ‘snow shoes’ from mountain ash timber growing on the lower mountain slopes.[6]

photograph by Charles H Kerry, Tyrell collection, Powerhouse Museum

This novel form of entertainment quickly became popular among the miners. As there was little requirement to use skis for touring or hunting, miners soon took to using skis as a diversion on days when the ground had frozen and snowfall made it impossible to continue work in the mines. The new pastime changed rapidly to downhill ski racing. In 1861 the three Norwegians founded the Kiandra Snow Shoe Club, later the Kiandra Ski Club and, today, the Kiandra Pioneer Ski Club.[7] In 2011, the Kiandra Snow Shoe Club was officially recognised by the International Skiing Federation as having organised ‘the first alpine ski races in the history of the sport’.[8]

Chinese connections

To a casual observer, therefore, the Museum’s skis could represent Norway’s celebrated contribution to Australian sporting history. What is not widely known, however, is that at Kiandra many of the most enthusiastic and skilled participants in the new sport of downhill skiing were Chinese men and women.

Between 60,000 and 80,000 Chinese people came to Australia during the colonial period, with the greatest influx, during the 1850s, oriented towards the goldfields in Victoria and, later, New South Wales.[9] Many of these were miners who came as indentured labour on the credit ticket system of employment, whereby tickets were financed by local co-operatives, traders or migration agents in return for regular repayments. From about 1860, individual Chinese, including storekeepers, butchers, bakers, tailors and doctors, also came to ply their trades throughout the region.[10]

Chinese people had first arrived at Kiandra in the winter of 1860, with the original number of arrivals increasing to about 700 by August.[11] Racism was endemic during the goldfields era, with Chinese depicted as ‘clannish, despotic and culturally alien’, in contrast to the idealised characteristics of mateship and equality that were attributed to Europeans on the diggings and to white settlers in general.[12]

Initially segregated from European skiers, Chinese skiers were often seen and portrayed as curiosities. Well-known Kiandra identity, Bill Hughes, recalled in a conversation with author Elyne Mitchell in 1985:

The most colourful picture which has been handed down to us is that of special races for Chinese miners on the field; a heat of a dozen or so Chinese streaming down Township Hill, screaming and shrieking with pig-tails flying in the wind, freely lambasting with their long poles any rival who happened to get ahead.[13]

According to a report in the Cooma Express, on 9 August 1895, ‘Ah Foo won the Chinese race, with Ah Fun coming second, and Ah Wung and Ah Yen tying for third place’. The race is described as ‘great sport to see the somersaults and grim death hold of the sticks’, which was ‘amusing to all except the four entrants, who were not good skiers’.[14] Reporting a ‘Novel Sports Meeting’ in August 1894, Freeman’s Journal describes the Chinese race, won by Ah Fat, as ‘exceptional fun’,[15] while in 1900, an article in the Australian Town and Country Journal recounts preparations for a snowshoe carnival in Kiandra where ‘Chinese and Chinese children, like animated Japanese dolls [were seen] all laughing, joking, jeering, falling here and there and everywhere’.[16]

However, Chinese skiers proved to be not just enthusiastic participants in this novel sport, but skilled competitors. According to historical records, the Kiandra Snow Shoe Club held its first ‘special’ race for Chinese members in the 1860s. From the late 1880s, and for the following 20 years, the achievements of Barbara, Margaret and Mary Yan, daughters of a Chinese goldminer of Kiandra, Tom Ah Yan, overshadowed those of many other women competing in downhill events. The Cooma Express, on 9 August 1895, described ‘Miss M Yan’ as ‘a perfect artist on the shoes’.[17] In 1896, the winner of the major downhill event was Frank Yan, who was presented with a gold fob watch and a pair of inlaid hickory skis, by New South Wales Member of Parliament, Mr G (Gus) Miller.[18]

Tyrell collection, Powerhouse Museum

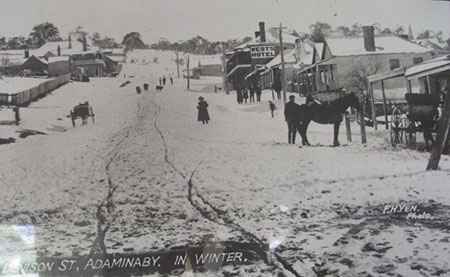

Old Adaminaby: the Yen family

By the end of December 1860, the Kiandra gold rush was over and most of the miners had left to seek their fortunes in other goldfields in New South Wales and Victoria. At about the same time as the 1860s gold rush in Kiandra, copper was discovered at nearby Kyloe. This, coupled with the gold rush, was responsible for the steady growth of the neighbouring town of Adaminaby, which by 1877 boasted a population of 400 to support its three hotels and three general stores.[19]

With the depletion of alluvial gold deposits, many Chinese who had worked as miners, or been associated in some way with the goldfields, took up other occupations. Increasing discrimination against Chinese migrants, coupled with legislation preventing their employment in trades, forced many into restricted areas of employment. Small businesses, where family members could be employed, became an obvious means of self-sufficiency and employment. It was probably for similar reasons that a young Chinese goldfields immigrant named Charles (Chun) Yen chose to remain in Adaminaby.

In the late 1850s, Yen, aged 16, arrived on the Kiandra goldfields with his friend John Booshang (Du Boo Shang). They travelled there, via Tumut, from Heungshan district, (later renamed Chungshan, now Zhongshan), in Guangdong province, China.[20] After the gold rush, they each established general stores in Denison Street and married twin sisters, daughters of Welsh and Irish immigrants Thomas Thomas and Johanna Shannahan of Cooma. John Booshang married Anastasia Thomas in 1881, while Charles subsequently married Jane Thomas in 1885.[21] Charles and Jane went on to have six children: Anastasia Jane (1886), Francis Henry (Frank) (1886), Maude (Bella) (1890), Arthur William (1894), Ada (1896) and Victor Edgar (1902).[22]

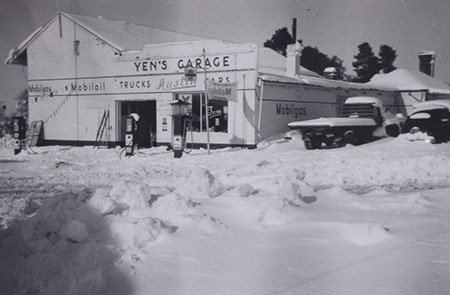

Throughout Australia, Chinese merchants generally expanded their businesses by conforming to the social and cultural needs of their local communities. Like other Chinese entrepreneurs, Charles Yen and his family soon diversified from their small goldfields shop into several family-operated businesses including a general store, butcher shop, picture theatre and service station/garage in Old Adaminaby. In the manner of most Chinese businesses, an adherence to Chinese values and practices meant that family members – in the Yen family, Arthur, Bella and Barbara (Geoff Yen’s sister) – were employed in the running of the store. Frank ran the local garage and was later joined by his son Geoff, who had completed a mechanical apprenticeship in Sydney. Rex (Reginald Thomas), Geoff’s brother, also worked at the garage and theatre before moving to Taree, on the mid-north coast of New South Wales.

courtesy Odette Yen

National Museum of Australia

In most respects, the Yen’s store was characteristic of others in rural towns across the country: located in the heart of the old town’s main business and shopping area and operating as a store from which anything and everything could be purchased.[23] And, like other Chinese storekeepers, the Yens imported and sold a diverse range of goods, including imported Chinese products, such as Ve-Tsin gourmet powder (pictured below), especially for members of the local Chinese community.

photographs by Judith Hickson

In her edited memoir of Adaminaby, It Doesn’t Snow Like It Used To: Memories of Monaro and the Snowy Mountains, Laura Neal quotes retired resident Trixie Clugston, who remembered Booshang’s store as having ‘had pies and lollies’ and Yen’s, which ‘had groceries, clothing and a butcher’s shop’.[24] Interviewed for the Cooma–Monaro Express in 2009, Cooma–Monaro Shire Councillor Jenny Lawlis remembered shopping at Yen’s store on her way home from school: ‘Sausages were occasionally on the menu from Mr Yen and it was the children’s job to bring them home. Sometimes as a little joke, Mr Yen would pop the children on the block and pretend to chop their heads off with his massive meat cleaver … I can’t remember being scared’.[25]

courtesy Odette Yen

National Museum of Australia

By the time of Federation in 1901, the lives of the Yen family were little different from those of other Chinese people who had established themselves and were engaged in many aspects of Australian life, including stores and businesses, importing enterprises, fraternal organisations such as the Chinese Masonic network and chambers of commerce. At this time, Chinese people also participated prominently in community organisations, while Chinese-language newspapers were numerous.[26] The Yens were actively involved in community events and routinely attended services at the Catholic church in Adaminaby. As a regular entrant in many of Adaminaby’s early agricultural shows, Charles won awards for a diverse range of livestock and activities, including for his ‘Berkshire Sow’ (1905), ‘Best Fat Ox’ (1906), and ‘Fat Cow’, ‘Cattle Dog’, ‘Pair of Light-buggy Horses’ and ‘Pony in Harness’ (1908).[27] He was also honorary secretary of the Adaminaby Cricket Club and newspaper articles record that family members regularly volunteered their services at community events such as shows and race days. Noted for his excellent piano playing, Arthur Yen was often called upon to provide piano accompaniment at local dances and balls. This level of engagement was typical of many Chinese Australians, who recognised the value of, and embraced membership and participation in, civic organisations.[28]

Nonetheless, in spite of their obvious commitment to their local community, members of the Yen family, like many Chinese Australians, were sometimes subjected to racism and vilification. In 1908, an axe was thrown at Charles’s son. The unprovoked, and what appeared to be deliberate attack occurred after abusive and racist remarks were made to the young man,while he and another man, Mr Barrett, were driving sheep along the road about five miles from Adaminaby. A local farmer’s son, John Watkins, was later charged with inflicting grievous bodily harm on Yen. According to a report in the Sydney Morning Herald, Yen sustained serious injuries ‘extending from the base of the thumb of the right hand across the wrist 2½ inches long, severing the radial artery and one of the … tendons of the wrist. The right ear was also cut through and he had a scalp wound behind the ear’.[29] Despite evidence given by Barrett that Yen had caused no offence to Watkins and had not responded to his racist taunts, Watkins was later aquitted by a jury in Cooma.[30]

Regardless of such setbacks, the hard work and enterprising nature of Charles Yen and other family members enabled them to purchase two nearby grazing properties. ‘Speedwell’ was located in Yen’s Bay on the southern side of Lake Eucumbene, and ‘Collingwood’, a larger property of about 800 hectares, stretched from Yen’s Bay to what is now the northern side of the lake. Of the original 800 hectares, only 240 were left after the flooding of the lake. Charles’s son, Arthur Yen, lived at Collingwood where he bred and trained racehorses, often winning prizes at the local shows for his stallions, mares and foals.[31]

Arthur was also well-known to those locals who liked a ‘flutter’ on the horseraces as the SP (starting price) ‘bookie’ or ‘turf accountant’ at the Adaminaby racecourse.[32] The racecourse was home to the thriving Adaminaby Jockey Club from about 1900. According to the March 1956 edition of the Australian Women’s Weekly, the racetrack’s ‘grandstands were packed for the final race meeting of the Adaminaby Jockey Club, which was run just prior to the flooding of the town in 1956.[33]

Little further personal information about Charles Yen’s life is known, except that he died suddenly, while in seemingly good health, in 1927. Surprisingly, the newspaper account of his death recorded that, although his wife Jane (née Thomas) had predeceased him in 1924, his mother, whose age was stated as 107 years, was still alive.[34]

And, while the extended family’s history is still being pieced together, the ‘Kiandra kick-ins’ in the National Historical Collection provide material evidence that, like most people who lived in this snowy alpine region, the Yen family were actively involved in the sport of skiing and were probably among the area’s pioneering skiers. References to the Yen family’s participation in ski races and competitions can be found in a range of early newspaper reports.[35]

Geoff Yen’s daughter, Odette, remembers her father as an active cross-country skier who led groups on cross-country expeditions during the 1940s and 1950s. According to Odette, she and her family learned to ski from early childhood by balancing precariously in front of their father while he skied down snowy slopes. They all survived to become keen and accomplished skiers.[36]

courtesy Odette Yen

National Museum of Australia

The loss of Adaminaby

In the 1950s, after a century of development, the town of Adaminaby and its established community were uprooted and relocated. While the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Authority was aware that the relocation was a sensitive issue with residents and took care to avoid legal issues, the lives and livelihoods of many people, such as Frank and Geoff Yen and their families, were profoundly affected by this event. Geoff Yen refused to sign a contract for the new buildings the authority was offering as compensation for his old buildings. He considered the amount offered insufficient to cover the loss of his house and business. The authority, however, went ahead with its plans, with the result that the Yens were required to repay loans for property when, prior to this they, like many others, had no outstanding debts. Geoff Yen sued the authority for greater compensation. The case lasted for 30 years until Yen agreed to withdraw, despite receiving nothing.[37]

According to the New South Wales Government Office of Environment & Heritage statement of significance, ‘the inundation affected most of the township except for four buildings that were located higher up the hill and allowed to stay in situ and the cemetery, sited on a hill, overlooking the old town … virtually no efforts were taken to record the town, collate historical records and salvage items of cultural value. Many significant items and places were destroyed when the Authority bulldozed historic cottages which were not considered to be good enough to relocate’.[38]

The trauma sustained after the town and valley were flooded was only one of a number of negative impacts on Adaminaby residents. Cut off from previously well-trodden routes to Jindabyne, Cooma and Berridale, and with the loss of valuable grazing country, including that of the Yen family, approximately half the population of the town and immediate district left due to the lack of job opportunities.[39] The old town blocks were often three or four hectares, on which a family could keep a cow or a horse, but the new blocks were only one-tenth of a hectare (quarter of an acre) in size.[40]

In his book, Returning to Nothing: The Meaning of Lost Places, historian Peter Read writes about the deep emotions aroused through the journeys people make (either real or imagined) to places, from their pasts, which no longer exist as they once were.[41] While conducting research for his book, Read interviewed many older residents of Adaminaby who remembered that the old town’s ‘barter economy and larger farms’ kept ‘many families out of debt even without regular employment. On the famous, roistering Saturday nights, stores remained open till 8.30’.[42] After the flooding of the old town, ‘[p]eople found they had to borrow money for the first time in their lives to pay for larger houses allocated to them with electricity and water connected’.[43]

photograph by Francis Yen

photograph by Francis Yen

Frank Yen, who was also a photographer of some renown in the district, refused to move to the new town of Adaminaby and went to live in Sydney where he died soon after. His son Geoff moved the wooden house from Collingwood to York Street in the new town. The remains of a small wooden house on the shores of Lake Eucumbene, that was once owned by the Yen family, are still standing not far from the area known as Yen’s Bay. Odette Yen describes the difficulty the family had adjusting:

Arthur … had the store and the butcher shop up the top end of the shopping centre and then he had the big storage shed out the back, but nothing like … no character like the old town … Dad … just went about doing his own thing … Adaminaby was where he was born and it was where he was going to die … it was his town … I think the biggest thing that upset Dad was that the town was changed dramatically … that was his biggest problem … life was never the same for the town once the town was moved … it was just an everyday struggle.[44]

courtesy Odette Yen

National Museum of Australia

According to Read, a huge cedar counter in the new Adaminaby store that was brought by previous owner, Arthur Yen, from the shop in the old town, remains a poignant reminder of loss. ‘Old residents shake their heads and say, “shifting the shop broke the old man’s heart”’.[45]

With the flooding of Old Adaminaby and the loss of their homes and businesses, came the loss of family histories. Like that of many other families, much of the material evidence of the Yens’ history lies submerged in mud at the bottom of Lake Eucumbene.

Museums, national identity and orientalism

It is generally accepted that, as spaces where geographically and historically distinct peoples encounter one another, and as active agents in the construction of knowledge, museums play an increasingly important role in shaping and transforming public imaginings about a nation’s past.

In 1983, Benedict Anderson, author of a defining work on nationalism and nation-building, Imagined Communities,[46] paid attention to the foundational role of museums in manufacturing a historical narrative that, in turn, profoundly shapes the way in which a national identity is constructed in popular imagination. On the other hand, museums, as places that challenge pre-conceived notions of national identity, can be viewed as sites of contestation, which are able to give voice and new meaning to under-represented ethnic and minority groups by linking their individual lives and stories, as participants in nation building, to a larger national narrative.[47]

The problematic nature of ‘oriental’ essentialism was introduced in Edward Said’s pioneering 1978 study of ‘Orientalism’, or the imagined distinctions between the ‘Orient’ and the ‘Occident’, East and West. In Said’s analysis, a complex and hegemonic Western image of the Orient emerged as an object for study, display and reconstruction.[48] In the post-colonial era, it is unsurprising that a recent review of national museums in Singapore has found that authorities in Singapore have strategically sought to subvert Said’s concept. Currently, these authorities are embarking on a campaign to make museum displays and tourist destinations in Singapore more ‘oriental’, after finding that their city has become ‘too modern and western for many tourists’.[49] The report concludes that ‘[w]hile Singapore self-orientalizes itself to attract more tourists, they are also introducing different sets of orientalist discourses’ which reflect the orientalist imaginings of foreign tourists to their country.[50]

For readers of Anderson, this is unsurprising. He believes a comparative focus on South-East Asia offers ‘special advantages, since it includes territories colonized by almost all the “white” imperial powers – Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, and the United States – as well as uncolonized Siam’. According to Anderson, the ‘present proliferation of museums around Southeast Asia suggests a general process of political inheriting at work. Any understanding of this process requires a consideration of the novel nineteenth-century colonial archaeology that made such museums possible’.[51]

Chinese identity in Australian museums

In Australia, similar orientalist processes, which create a separate identity for Chinese migrants to Australia, are evident in museums. Attention is often drawn to Australia’s Chinese heritage through objects – for example, goldfields artefacts, brocaded silk, opium pipes, blue and white porcelain or shards of pottery – which symbolise a romanticised European image of China, and emphasise the ethnic and cultural distinctiveness of Chinese Australians, both constructed and imagined.[52]

In looking at the construction of an Australian national identity, historian John Fitzgerald believes that this approach diverts attention from the ways in which Chinese people have come together with other communities, as Australians, to contribute to the social, cultural and sporting histories of our nation. In Fitzgerald’s opinion, ‘as a rule [these objects] commemorate not the Chinese heritage of Australia, but White Australia’s exotic links with a remote civilisation in China … The names [and voices] of [identifiable individuals] who used these artefacts are generally omitted from public displays’.[53] Moreover, Fitzgerald considers that ‘Chinese … typically feature in [museum displays] as an ethnic group rather than as identifiable individuals … [as] a fortuitous link between the region and ‘Asia’. They rarely appear as Chinese Australians or as families or individuals from China who happened to live in the area under the impression that they were Australian’.[54]

There is, therefore, capacity for the National Museum of Australia and other institutions to identify objects like the Yen family’s skis, which, as less culturally distinct objects, are able to articulate a less well-represented, less ‘orientalised’ history of the lives of Chinese migrants to this country. Such objects, with their associated histories and stories, are able to reveal the extent to which Chinese migrants have responded to social and environmental circumstances to become successful participants, valuable contributors and agents of change in Australian life and society in significant, often untold ways. The potential exists to create a museum display narrating a successful Chinese migration story that also records the ways in which people adapt, react, relate to and interact with places and with each other.

Most importantly, the skis are able to disclose a more refined, less determinate, narrative of Chinese people, whose sense of themselves as Australians was based on a commonly inhabited and similarly experienced past with other settlers, as opposed, for instance, to one based on ethnicity or race.[55] Such a history allows us to confront racism by challenging stereotypes of an exoticised oriental ‘other’ and to see, as Fitzgerald would have us do, Chinese settlers and their descendants as individuals, who have contributed, in common with other migrants, to the complex nature and architecture of Australia’s cultural identity.[56]

photographs by Judith Hickson

I would like to thank Odette Yen for her patience and generosity and for giving her permission to share the Yen family story with a wider audience.

Endnotes

1 Grooves on the underside of skis were a common feature of Scandinavian and Finnish skis: E John B Allen, The Culture and Sport of Skiing: From Antiquity to World War II, University of Massachusetts Press, Massachusetts, 2007, p. 10.

2 Norman W Clarke, The World’s First Alpine Ski Club, 2nd edn, N Clarke, Sydney, 2012.

3 M Lund, ‘A short history of skis’, International Skiing History Association, 2011, www.skiinghistory.org/index.php/2011/08/a-short-history-of-skis.

4 Allen, The Culture and Sport of Skiing, p. 70.

5 ibid., p. 22.

6 Clarke, The World’s First Alpine Ski Club, p. 12.

7 ibid. Wendy Cross (The First One Hundred Years, Walla Walla Press, Petersham, NSW, 2012) challenges Clarke’s assertions of the foundation date and names of founding members of the Kiandra Ski Club. Clarke appears to refute Cross’s claims in this revised edition of his book in which he provides detailed evidence from newspaper reports and other primary sources.

8 GF Kasper, President of the International Skiing Federation, Letter to Kiandra Snow Shoe Club, 10 May 2011, cited in Clarke, The World's First Alpine Ski Club, p. 21.

9 C Choi, Chinese Migration and Settlement in Australia, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1975, p. 22; C Choi, ‘Occupation change among Chinese in Melbourne’, Race & Class, vol. 11, 1970, 303–11 (p. 303).

10 L Smith, ‘Identifying Chinese ethnicity through material culture: Archaeological excavations at Kiandra, NSW’, Australasian Historical Archaeology, vol. 21, 2003, 19–20.

11 ibid.

12 K Reeves & B Mountford, ‘Sojourning and settling: Locating Chinese Australian history’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 42, no. 1, 2011, 111–25 (p. 114). Also see J Fitzgerald, Big White Lie: Chinese Australians in White Australia, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2007, p. ix.

13 ‘Bill’ (William) Hughes, the son of an Australian Champion skier and grandson of an original 1860 Kiandra pioneer, grew up in Kiandra, went to school with many of the families there and became a very distinguished mountaineer and authority on the district. Hughes related to Elyne Mitchell that he was told that the Chinese ski races were held on a day set aside for them, when: ‘Brake sticks were permitted, and as many as ten runners often started in a race down the Kiandra Slam, the width of which is but two chains. Consequently, fouling was frequent and the long sticks were often used successfully by the indiscriminate to fell a rival … “The Pats”, with pigtails flying and sticks swinging, must certainly have presented an animated scene unique in skiing history. Fights with skis and sticks were frequent, as someone was nearly always to be found who object[ed] forcibly, to being “accidentally” tripped up or hit over the head with an eight foot pole’. Elyne Mitchell, Discoverers of the Snowy Mountains, cited in Friends of Thredbo,’150 years of Australian alpine skiing, 1861–2011, anniversary newsletter’, issue 48, June 2011, www.kiamaalpineclub.org.au/kac-articles/newsletters/ths-thredbo-museum-flyers/ths-thredbo-museum-flyer-201106.pdf.

14 Quoted in Lindsay Smith, ‘The Chinese in Kiandra’, 2004, Kiandra Historical Society, www.kiandrahistory.net/chinese.html

15 ‘Snowshoe races at Kiandra’, Freeman’s Journal, 11 August 1894, p. 9.

16 N Lockyer, ‘Ski racing on the Snowy Mountains: The glory of the snow’, Australian Town and Country Journal, 11 August 1900, 37–8.

17 ibid.

18 Norman W Clarke, Kiandra – Gold Fields to Ski Fields, N Clarke, Sydney, 2006, p. 42.

19 Statement of significance, ‘Old Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene, including relics and moveable objects’, New South Wales Heritage Register, 2007, www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5060670

20 Smith, Chinese in Kiandra.

21 Kiandra Historical Society, History of Kiandra, www.kiandrahistory.net

22 Details obtained from New South Wales Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages, Historical Records, www.bdm.nsw.gov.au/familyHistory/searchHistoricalRecords.html

23 Odette Yen, pers. comm. 2012. Also see J Wilton, ‘Wing Hing Long: From store to museum’, Golden Threads, Powerhouse Museum exhibition website, hosting.collectionsaustralia.net/goldenthreads/stories/whl.html

24 L Neal, ‘It Doesn’t Snow Like It Used to’: Memories of Monaro and the Snowy Mountains, Stateprint, Sydney, 1988.

25 S Byrnes, ‘That was life in Old Adaminaby’, Cooma-Monaro Express, 6 October 2009, www.coomaexpress.com.au/news/local/news/general/that-was-life-in-old-adaminaby/1641704.aspx?storypage=1

26 Fitzgerald, Big White Lie.

27 ‘Adaminaby P. and A. Association’, Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, Friday 14 April 1905, p. 25; ‘Agricultural shows: Adaminaby ‘, Australian Town and Country Journal, Wednesday 4 April 1906, p. 14; ‘Agricultural shows: Adaminaby’, Sydney Morning Herald, Friday 3 April 1908, p. 4.

28 Fitzgerald, Big White Lie.

29 ‘Wounded with an axe: sensational charge’, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 September 1908, p. 9.

30 ‘Obituary: Mr Charles John Yen’, Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 22 June 1927, p. 4.

31 ‘Agricultural shows: Adaminaby’, Sydney Morning Herald, Monday 4 March 1935, p. 7.

32 SP bookmaking is a form of off-course gambling that was legal in New South Wales in the 1920s, but later prohibited through state legislation passed in response to pressure from anti-gambling movements. D Dixon, ‘Illegal betting in Britain and Australia: Contrasts in control strategies and cultures’, in J McMillen (ed.), Gambling Cultures: Studies in History and Interpretation, Routledge, London, 1996, p. 86.

33 ‘Back to Adaminaby’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 4 March 1956, pp. 20–22.

34 ibid.

35 A National Library of Australia Trove digitised newspaper search highlighted a number of articles referring to the Yen family of Adaminaby and their participation in skiing competitions.

36 Odette Yen, pers. comm., 1 June 2012.

37 ibid.

38 Statement of significance, ‘Old Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene’.

39 ibid.

40 P Read, ‘The intuitions of place’, paper presented at WA 2029: A Shared Journey, 17–19 November 2004.

41 Peter Read, Returning to Nothing: The Meaning of Lost Places, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Melbourne, 1996.

42 Read, ‘Intuitions of place’.

43 Statement of significance, ‘Old Adaminaby and Lake Eucumbene’.

44 Odette Yen, pers. comm., 1 June 2012.

45 P Read, P 1996, ‘Remembering dead places’, The Public Historian, vol. 18, no. 2, 1996, 25–40 (p. 37).

46 B Anderson, Imagined Communities, Verso, London, 1991.

47 S Dudley, AJ Barnes, J Binnie, J Petrov& J Walklate (eds), The Thing About Museums: Objects and Experience, Representation and Contestation, Routledge, New York, 2011.

48 E Said, Orientalism, Pantheon Books, New York, 1978.

49 Can-Seng Ooi, ‘Orientalist imaginations and touristification of museums: Experiences from Singapore’, Copenhagen Discussion Papers, Asia Research Centre, 2005, p. 1.

50 ibid., p. 18.

51 Anderson, Imagined Communities, pp. 163–4.

52 See, for example, K Schamberger, ‘“Still Children of the Dragon”? A review of three Chinese Australian heritage museums in Victoria’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 42, no. 1, 2011, 140–47.

53 Fitzgerald, Big White Lie, p. 212.

54J Fitzgerald, ‘Another country’, Meanjin, vol. 60, no. 4, 2001, 59–71 (p. 61).

55 J Brockmeier, ‘Remembering and forgetting: Narrative as cultural memory’, Culture and Psychology, vol. 8, no. 1, 2002, 15–43.

56 Fitzgerald, ‘Another country’, p. 61.