Phar Lap

From racecourse to reliquary

Introduction

The physical remains of the racehorse Phar Lap can be found on permanent display in three separate cultural institutions in Australia and New Zealand. His heart is at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra, his mounted hide at the Melbourne Museum campus of Museum Victoria, and his articulated skeleton at Te Papa Tongarewa in New Zealand.

The life stories of preserved animals held in museum collections are often incorporated into their ‘afterlives’, the term used by historian and museologist Samuel Alberti to describe the post-mortem existence of animals whose biographies extend beyond death.[1] Many of these animals were once popular zoo exhibits, and today their individual histories are integral to their interpretation as objects, but are rarely the reason for their preservation in the first place.[2] In contrast, Phar Lap’s story was the very reason for his selection for the ‘afterlife’.

The preservation of Phar Lap’s remains was in keeping with the 19th-century tradition of memorialising favoured racehorses, especially through the art of taxidermy,[3] a practice that was well-established at the time of his death. In the ensuing years the interpretation of these preserved and publicly displayed remains has subtly changed, until now they are ascribed with a significance that exceeds the circumstances of their unremarkable creation. It can be argued that in a secular society such as Australia, narratives of national identity replace the myths of Christianity in articulating ideas of who we are as a nation. The story of Phar Lap forms one of this country’s cornerstone cultural myths, and its repeated telling, in conjunction with the perpetual display of his remains, has brought about the horse’s progression from racetrack to reliquary.

The animal ‘afterlife’

The word taxidermy comes from the Greek root words taxis (arrangement) and derma (skin), and literally means the arrangement of skin. Clearly, not all of Phar Lap’s remains fit this definition. Yet the animal afterlife as defined by Alberti is not confined to taxidermic specimens.Phar Lap fits within that category defined by academic researcher Hannah Paddon as a ‘mascot animal’. Mascot animals are ‘those specimens of biology on display which have an elevated meaning for visitors and museum staff alike ...[that] remain significant to museum audiences even after long periods of time’.[4] The mascot animals that dominate the literature on this topic are almost exclusively species from abroad,[5] such as Maharajah the elephant, now on display at Manchester Museum, and Alfred the gorilla, now at Bristol Museum. The exotic origins of these animals are all that is required to draw the attention of audiences. Phar Lap, on the other hand, was a horse, which was in itself unremarkable. Yet he was regarded as extraordinary for being more than just a horse.

A comparable instance of an ordinary animal being elevated to the status of extraordinary, and continuing to have a presence through his taxidermic afterlife, is Balto the dog.

photograph by Dan Coulter (via Flickr)

Balto was the lead sled dog in the final leg of a relay that carried a life-saving diphtheria antidote into the snow-bound town of Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Balto became a celebrity, and following his death in 1933 his remains were taxidermied and placed on display in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where they remain to this day. Writing about Balto, historian of taxidermy Rachel Poliquin points out that:

Balto was preserved because he was more than ‘just’ an animal. He was a courageous and intelligent saviour, accomplishing what no human could have done ... On the other hand, Balto was preserved because he was ‘just’ an animal. ... Human heroes are not taxidermied.[6]

Like Balto, Phar Lap was a hero to his human community while alive. Further, both these animals are commemorated in the running of an annual race. In Balto’s case this takes the form of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, which starts on the first Saturday in March and is run along the route of the diphtheria rescue mission, ostensibly in memory of Balto and his canine associates. Likewise, although the Melbourne Cup predates and transcends the Phar Lap phenomenon, the race has come to function, at least in part, as an annual commemoration of both the horse himself, and his 1930 Melbourne Cup victory.[7]

These annual events provide ample opportunity for the media to revisit the significance of the animals associated with them, ensuring they are never long out of the public mind, while the permanent display of their physical remains ensures they are never out of the public eye. Writing of another mascot animal, Alfred the gorilla, Paddon states that ‘his presence in the museum has ensured that he continues to build new memories for those who observe him’. [8] Memory is not a passive process; it is actively constructed through the gaze of the visitor.[9] Yet it also occurs across multiple levels – from the individual to the collective. Susan Crane writes about museums as places where memory is objectified, ‘not belonging to any one individual so much as to audiences, publics, collectives, and nations, and represented via the museum collections.’[10] The presence of mascot animals such as Alfred and Phar Lap in the museum context both facilitates the construction of individual memories, and influences the collective memory.

Phar Lap’s living history

The New Zealand-born Phar Lap was a large chestnut gelding who dominated Australian racetracks in the late 1920s and early 30s, and is credited with giving hope to a generation during the hard days of the Depression.[11] His popularity was not just due to the fact that he won – and convincingly – but also due to his humble origins. His is a classic rags-to-riches tale that has been retold many times, not only in the cultural institutions that house his remains, but also through books, film, television, and an opera.[12] While most mascot animals attain local fame, Phar Lap’s mascot status is nation-wide.

The Phar Lap story is as follows: a down-on-his-luck Sydney trainer named Harry Telford convinced an American entrepreneur, David J Davis, to buy an unnamed colt on offer at the Trentham Sales in New Zealand. Telford was attracted to the colt on the basis of his bloodlines, but when the young horse arrived, Davis is said to have taken one look at him and baulked. Telford negotiated a three-year lease of the horse, who then went on to win 37 of his 51 starts, including the 1930 Melbourne Cup. Though Phar Lap was undoubtedly a household name for many before this, the Cup victory extended his reputation and popularity beyond the race-goers and punters, and he was embraced by the broader Australian public.

In 1931 Telford’s lease expired, and he and Davis became co-owners. It was Davis’s idea to send the horse to America to contest the 1932 Agua Caliente handicap, the richest race in the world at that time. Phar Lap won the race with ease, but just 16 days later, on 5 April 1932, he was dead. A necropsy was carried out, and the official findings were that he died of an acute colicky inflammation, though it was noted at the time that ‘the factors responsible for the acute inflammation have not been determined and probably will never be determined’.[13]

Phar Lap’s ‘afterlife’

There is something ritualistic in the treatment of favoured racehorses post-mortem. After death, the head and heart of a good horse would traditionally be buried.[14] A great horse might be commemorated through the transformation of their hooves or tail into decorative objects (the parallel with the Victorian practice of collecting a lock of hair from a loved one before or after death and fashioning it into a memento, often a piece of jewellery, is no coincidence; both traditions have their historical origins in this era).

Australian Racing Museum

A truly exceptional horse, such as Carbine (winner of multiple races including the 1890 Melbourne Cup), could well expect to have his skeleton and hide mounted. These items simultaneously serve as symbols of the racehorse and as a reliquary.[15] Very rarely, horses were buried intact by their doting owners, such as the Depression-era racehorse Peter Pan, who in 1941 was buried ‘whole’, in accordance with custom in such instances, in his favourite paddock, facing the rising sun.[16] (This event did not preclude the removal of his hooves, mane, and tail prior to burial for the manufacture of an inkwell, a pincushion, and similar mementoes.)[17]

photograph by Jessica Owers

The three separate objects that together embody Phar Lap’s ‘afterlife’ all serve to tell the life and death story of Phar Lap, and for the most part they function as interchangeable symbols of the horse himself. However, and crucially, this was not the case at the time of Phar Lap’s death, when each class of remains was treated very differently.

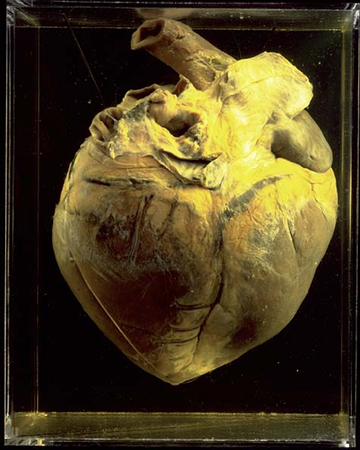

Phar Lap’s heart was removed immediately after death by the stable vet Bill Nielsen, who mounted it in preserving fluid and dispatched it to Sydney. There it had been requested by Dr Stuart McKay, who had an interest in racehorse physiology and was eager to see what insights the heart might give. It is almost certain that had Phar Lap’s heart been of an average size, it would have been disposed of; most likely returned to Telford for burial, as a mark of respect to the horse and in keeping with racing tradition. Instead, finding it to be of an unusually large size, McKay suggested that the heart be donated to the Australian Institute of Anatomy in Canberra.

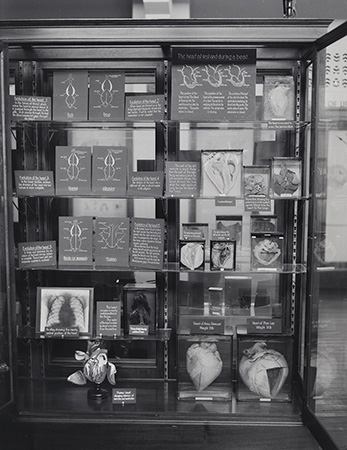

National Museum of Australia

Thus the heart was originally collected for its scientific, rather than cultural, value. In the words of the institute’s director, Sir Colin MacKenzie, ‘Phar Lap has been pronounced by experts as the most perfect anatomical specimen of a horse ever known and the heart, therefore, is of especial interest to the comparative anatomist’.[18] Environmental historian Libby Robin writes, ‘[MacKenzie] was interested in the exceptional, and what it could tell an anatomist or a surgeon about the “normal” and the evolution of “advanced” forms’.[19] Displayed at the Institute of Anatomy next to the 2.7-kilogram heart of an army horse, Phar Lap’s massive 6.35-kilogram heart spoke evocatively of the ‘advanced’ racehorse. It proved to be a popular display.

In 1981 the heart, along with the rest of Mackenzie’s material, was transferred to the newly-formed National Museum of Australia, as part of its founding collection. This point marks the transition of the heart from biological specimen to historical object. Sociologist Tony Bennett writes about the past being historicised as a means of ‘nationing’ populations.[20] Though Phar Lap’s heart was a popular exhibit at the Institute of Anatomy, its transformation to a symbol of nationhood was not realised until it was historicised. This occurred not least through its inclusion in the National Historical Collection, under the auspices of the National Museum of Australia.

Today, the heart is on permanent display at the Museum, housed in its own dedicated showcase, with muted lighting powered by a time-delay sensor. It is known as the Museum’s most requested object.[21] In the current iteration of its ongoing presentation it is accompanied by a display on Flemington Racecourse and the Melbourne Cup. That its scientific relevance has not been forgotten however, is demonstrated by a sliding panel along the surface of the showcase which allows comparison with a typical horse heart.

Unlike the heart, the skin was not seen to have any scientific value at the time of Phar Lap’s death, and was sent to be mounted for display by the Jonas Brothers of New York, whose taxidermic work included mounting natural history specimens for institutions such as the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian. Paid for by Davis, [22] and used by him in several public relations exercises while still in the United States, the mount seemed destined to be the focal point of Phar Lap fandom from the outset, as this excerpt from a rhyming eulogy, published just days after the news of the horse’s death, demonstrates:

Phar Lap’s dead and can't be deader;

Phar Lap’s gone beyond recall;

Taken one great equine header

To the grave that covers all.

Said we grave? If so excuse us;

Bones and hide will come back here,

To instruct and to enthuse us,

Lest we do not shed a tear.

Here he’ll stand within a stable,

Where we’ll bow a reverent head,

And upon a marble table

That last cable –

Phar Lap’s dead.[23]

The mention of the taxidermied animal standing ‘within a stable’ reinforces the notion of the skin as a theatrical object, placed within a suitable mise en scène. Indeed, soon after the mount was completed, it was paraded, on the back of a lorry, around New York’s Empire Rose racetrack. This somewhat uncomfortable juxtaposition between the territory of living racehorses and the dead Phar Lap was not new. It was common practice to exhibit the remains of popular animals in the menageries and circuses of Victorian England. In one case the skeleton of the elephant Chuny was exhibited in the very cage he had inhabited in life,[24] and Phar Lap’s mount was paraded around Flemington Racecourse as recently as 1980, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of his Melbourne Cup win.

The original theatrical intent of the mounted skin is further evidenced when comparing its parallel treatment to that of the heart: when the heart was in transit between the United States and Canberra in 1932 it was displayed in Sydney at the Australian Museum,[25] whereas when the skin arrived in Melbourne several months later, it was displayed in the upstairs foyer of the Capitol Theatre.[26]

As stated above, there is an established tradition in the racing world of transforming horse hooves and other parts, such as tails, into decorative objects.

Australian Racing Museum

Arguably the only difference between such objects and the mounted hide of Phar Lap lies in the latter’s financial cost. Davis had the funds to create a life-sized memento of his horse, and so he did. The fact that this memorial could easily travel to racetracks where it could be shown around, probably for an appearance fee, may also be relevant to Davis’s decision to mount the skin. According to cultural historian Geoffrey Swinney, such a representation ‘provide[s] a means for the animal’s celebrity to transcend death, thereby affording new forms of engagement in human society’.[27] Certainly the mount allowed Phar Lap’s celebrity to transcend death and, at least for Davis, encouraging such new forms of engagement represented a good business opportunity.

Re-presenting an animal that had been popular in life to capitalise on its celebrity after death was most successfully engineered by PT Barnum, the American showman. When his famous elephant, Jumbo, died in 1885, Barnum immediately ordered him to be mounted, stating that ‘Jumbo dead is worth a small herd of ordinary elephants’.[28] No stranger to theatrical illusion, Barnum requested that in death Jumbo be made physically larger, despite the fact that he was already said to be the largest African elephant in the world.[29]

Despite the clearly non-scientific nature of its creation, in a rather ironic twist the Phar Lap mount has recently turned out to be of far greater scientific value than the heart, by proving integral to solving the mystery of what really killed Phar Lap. Molecular analysis of hairs from the skin have conclusively proved that Phar Lap’s death was caused by arsenic poisoning, and that he ingested a massive dose of it some 35 hours before he died.[30] Thus the question of how the horse died has been solved, though, as foretold by the necropsy report, the reason why will probably never be known. (The most widely-held theory today is that the overdose was accidental, as arsenic was a common ingredient in the various homemade tonics prepared for racehorses by trainers.)

The third and final of Phar Lap’s mortal remains, his articulated skeleton, is probably the least unusual body part to undergo transformation into a museum object. MacKenzie is quoted in the press the day after the horse’s death, urging that the skeleton of the horse be installed at the Institute of Anatomy as a ‘guide to breeders and an historic object’. [31] Clearly MacKenzie saw the significance of the skeleton as being both scientific and historic. Displaying the skeleton of a great horse was not unusual – the skeleton of Carbine was already on display at the Melbourne Museum, and so the bones of Phar Lap were initially donated to that institution alongside the hide. Soon after, the bones were given to the New Zealand Government, who passed them on to the Dominion Museum in Wellington, where they languished unmounted for some five years.[32] Eventually, racing writer SV McEwen raised a subscription to enable the skeleton to be articulated, and it was finally displayed in 1938.[33]

The skeleton is now on display at Te Papa Tongarewa, the national museum of New Zealand. In 2009 a disgruntled fan made headlines when she complained that the horse’s skeleton looked hunched and inaccurate, prompting Te Papa to respond that the skeleton’s significance was primarily as an example of 1930s taxidermy.[34] Finally however, in October 2011, it was decided to reassemble Phar Lap. According to the curator of terrestrial vertebrates at Te Papa, ‘there had long been a debate about whether it was more important to maintain the 1938 articulation as an historic exhibit, or whether it should be an anatomically correct posture. The latter argument has finally been accepted’.[35] Note here that it is a curator of terrestrial vertebrates, rather than of social history, who is the spokesperson for the remains, and that at no point does he mention the significance of the bones themselves, only their anatomical correctness. Interestingly, the bones were re-articulated in 2012 to mimic the Phar Lap mount, and a full-size photograph of the mount stands as a backdrop to the re-articulated skeleton.[36]

Cultural theorist Michelle Henning writes that ‘museum [taxidermy] models or specimens are never neutrally exhibited. They do not appear before us as simple matters of fact, but are produced by various exhibition practices, contextual framing, institutional conventions’.[37] Though members of the public championed Phar Lap’s cause in New Zealand, the ongoing reluctance on an institutional level – first the government, then the Dominion Museum, and finally Te Papa – to historicise the horse casts into sharp relief the particular reverence that Australians of all walks of life have had for the horse. In Australia, upon hearing the news, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons himself made a statement regarding the tragedy of Phar Lap’s death.[38]

Phar Lap’s heart at the National Museum of Australia

photograph by Jason McCarthy, National Museum of Australia

At a Family Festival Day to celebrate the opening of the National Museum of Australia’s new Landmarks gallery in June 2011, visitors encountered Phar Lap’s heart for the first time in its new display. The most common scene that was played out was the adult guiding the child to the object, or joining the child if they were already there, and saying something along the lines of, ‘Look at this – this is a very important heart, it belonged to a very important horse called Phar Lap’.[39] Very few people explained to their children why Phar Lap was so important, simply stating his significance as a given.

From this, the idea of exploring the importance of Phar Lap to Australians through visitor research was conceived. A simple two-page survey, for face-to-face delivery, was devised and applied to visitors who stopped at the Phar Lap exhibit over a three-week period in July 2011. The study was by no means exhaustive, but it did produce some interesting results.

The vast majority of respondents – 89 per cent in fact – either agreed or strongly agreed that Phar Lap’s heart was an important object, but when asked to expound upon why they felt it was important, half were unable to say more than that Phar Lap himself was important. Almost a quarter of respondents mentioned the size of the heart, while 18 per cent felt its importance was because it was a story from the past. Only 14 per cent mentioned Phar Lap’s role during the Depression, and only one person mentioned his Melbourne Cup victory.

In summary, the overarching view of those surveyed was that Phar Lap’s heart was important because it was big, and because it had belonged to Phar Lap, who was a story from the past. Taken at face value, this analysis failed to articulate the great reverence that Australians seem to hold for the horse and, by association, his physical remains. Yet the prevailing feeling among respondents was that the heart was important, and its status as the most requested object of the National Museum would seem to support this.

Around the same period, the display of the Phar Lap mount at Melbourne Museum attracted the ire of writer and academic Amanda Lohrey, her accusation being that it was ‘a typical trophy exhibit – it’s there because it’s there’.[40] To counter Lohry’s inferred allegation of poor interpretation, it is worth noting that in both institutions the interpretation is present, with ample text discussing Phar Lap’s humble beginnings and his role in Depression-era Australia.

Writer and broadcaster John Harms might be correct in his assertion that ‘we are not a contemplative people. We’re not given to sitting around in pubs discussing why Phar Lap is a national hero. He just is’.[41] But perhaps, in trying to get to the bottom of Phar Lap’s significance to today’s Australians, the wrong questions were being asked; perhaps, instead of asking why the remains were significant, the questions should have centred on what the remains actually meant to people.

From racecourse to reliquary

While relics of saints, and embalmed human remains, do not qualify as taxidermy,[42] there is no reason that taxidermied or other biological remains cannot become relics. In a secular society, the central myths of Christianity must be replaced by other narratives in constructing a national identity.[43] As early as the 1890s, author Mark Twain described Melbourne as ‘the mitred Metropolitan of the horse-racing cult’, and Flemington racecourse as ‘the Mecca of Australasia’.[44] Clearly the notion that horse racing is akin to a religion in Australia is not new.In a joint paper, scholar of religious studies Carole Cusack and scholar of tourism studies Justine Digance argue that the Melbourne Cup is a secular site of pilgrimage for Australians, [45] contending that ‘the experience of the “sacred”, traditionally the preserve of the churches, has floated free, and attached itself to phenomena that were traditionally regarded as “secular”’.[46] The centrality of the Melbourne Cup myth to the Australian concept of national identity is evident through its adoption and reiteration by official government portals such as Australia.gov.au[47] and the National Museum of Australia. Marketed as ‘the race that stops the nation’, the Melbourne Cup purportedly espouses such notions as egalitarianism and the ‘fair go’.[48]

The Melbourne Cup is inextricably linked with the legend of Phar Lap, and the Phar Lap story itself emphasises several key themes that resonate with commonly held perceptions of ourselves as Australians.[49] These themes, as articulated by Cusack and Digance, are the Aussie battler made good, the sporting hero, and the early death that symbolises unfulfilled potential.[50]

As previously stated, the annual nature of the race provides ample opportunity for Phar Lap remembrance, and in this way may be compared with other annual religious observances that involve the repetition of familiar narratives, such as Christmas and Easter. In a further echo of the economic clout of these religious holidays, the Melbourne Cup has been demonstrated to have a positive effect on the Australian stock market.[51]

If Phar Lap’s heart is the National Museum’s most requested object, and his hide is the Melbourne Museum’s most popular object,[52] it seems plausible to suggest that there may be a sense of pilgrimage associated with visiting these secularly sacred objects. Cusack and Digance define secular pilgrimage as ‘the undertaking of a journey that is redolent with meaning ... more focused on experiencing something magical that punctuates the normal humdrum patterns of daily life’.[53] When we consider cultural theorist Stephen Greenblatt’s analysis of the museum experience based on resonance and wonder, with museums as places of ‘enchanted looking’,[54] it seems that Cusack and Digance’s description of secular pilgrimage might be applied to those seeking to encounter Phar Lap’s remains at either the National Museum of Australia or the Melbourne Museum. Indeed, Cusack and Digance themselves refer to these two institutions as ‘reliquary sites’.[55] Many of those who wrote letters of sympathy to Telford and Davis immediately following the news of the horse’s death referred to their joy that the horse’s remains were being returned to Australia. One correspondent wrote ‘Though it will be a sad day for me, I must see him’.[56]

Museums play an integral role in constructing and articulating narratives of national identity and these narratives can be hotly contested, as evidenced by ‘the history wars’ – the vigorous debate centred on the National Museum of Australia when it first opened in 2001. Historian Benedict Anderson wrote about nations as ‘imagined communities’, and claims museums as one of the ‘three institutions of power’ in shaping ideas of nationhood and nationalism.[57] The housing and display of Phar Lap’s remains in the museum context, rather than in a private collection (or the upstairs foyer of the Capitol Theatre), automatically ascribes to them a certain cultural and social value.

The way Phar Lap was depicted after his death, either through language or imagery, had a sanctifying effect, and further consolidated his position as a figure of reverence. The 1932 painting Phar Lap before the Chariot of the Sun, by JL Fleury, shows the horse at the head of Apollo’s chariot surrounded by angels and the Nine Muses, galloping on a cloud bed below which can be seen the landforms of Australia and New Zealand.[58] After Phar Lap’s death Harry Telford described him as ‘an angel ... I’ve never practiced idolatry, but by God I loved that horse’.[59] A member of the public wrote, ‘there will only ever be one Phar Lap and his work will last forever’.[60]

Further, the horse’s mysterious death in the prime of his life has the resonance of martyrdom about it, and Phar Lap was almost instantly memorialised by the people of Australia. The mounted hide served as a focal point for this commemorative act, drawing large crowds to the National Gallery and Museum (as it was then called) in Swanston Street, Melbourne. This form of local worship is depicted in the well-known artwork by Eric Thake titled Gallery Director, or, This Way to Phar Lap.[61] The 1954 linocut shows a caricature of the director, Daryl Lindsay, pointing past a hallway of artworks to the silhouette of the mounted hide, before which human figures are prostrating themselves, echoing the earlier reference to heads bowed in reverence featured in Dryblower’s rhyming eulogy.

photograph by Isa Menzies

The high quality of the Phar Lap mount allows audiences to immediately engage with, and easily relate to, the horse.[62] The iconic pose created by the Jonas Brothers, which was drawn from photographs of Phar Lap while still alive, emphasises the object’s likeness to the living horse, posed nobly with head up and ears erect. As Swinney points out,

[the model] through its pose connotes that particular animal in life ... Such models are themselves reliquaries, each fashioned into the appearance of some aspect of the celebrated individual that it memorialises.[63]

Following the immediate appeal of the mount, in subsequent years the heart, and most recently the skeleton, have joined the hide to emulate a ‘Holy Trinity’ of objects in which the veneration of Phar Lap is situated.

In 2010 this veneration was highlighted when Victorian Racing Minister Rob Hulls proposed reuniting the Phar Lap body parts, as part of the celebrations surrounding the 150th anniversary of the Melbourne Cup. It is unclear what Hulls hoped to achieve by reuniting the parts of the horse – perhaps a miracle? As one commentator put it, ‘What do they think he is? Phar Lap is unique, not Humpty Dumpty’.[64]

photograph by Isa Menzies

Concluding thoughts

It is evident that Phar Lap’s remains originally fitted within the traditional post-mortem memorialisation of well-performed race-horses, and were intended as either objects of scientific study (the heart), theatricality and entertainment (the hide) or as traditional objects of display (the skeleton).However, in subsequent years these physical remains have undergone a transformation in meaning. The heart was historicised through its incorporation into the National Historical Collection of the National Museum of Australia; the mount, which was the focal point for Phar Lap fandom from the outset, went from theatrical prop to scientific study; and, through public pressure, the skeleton has been transformed from an object of type to the third element of the Phar Lap trinity. As Rachel Poliquin states, ‘all taxidermy has a life of its own. Any particular piece is hardly rooted to the particular circumstances of its creation’.[65]

Phar Lap’s presence in Australia’s cultural institutions and the annual opportunity of remembrance afforded by the Melbourne Cup mean that the horse continues to be a central figure in Australian narratives of national identity. Both social commentators and museum audiences alike continue to acknowledge his importance, to visit his remains, and even, as occurred in New Zealand, to influence their display. As such, Phar Lap’s physical remains appear to have attained the status of quasi-religious relics. Thus the horse himself has achieved a form of secular sainthood.

Endnotes

My thanks to Kirsten Wehner of the National Museum of Australia, who in her role as senior curator of the Landmarks gallery supported me to undertake some of this research. Thanks also to Lorinda Cramer of the Australian Racing Museum in Melbourne for all her assistance. A version of this paper was presented at the Museums Australia Conference 2011.

1 Samuel JMM Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals: A Museum Menagerie, University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, 2011.

2 The zoo animals in question tended to be exotic specimens, and as such they lent themselves to becoming natural history specimens after death.

3 Stuffed, Snapped, Stitched and Pickled: A Collection of Curios and Keepsakes from the Turf, exhibition at the Australian Racing Museum, 15 February – 3 June 2001.

4 Hannah Paddon, ‘Biological objects and mascotism: The life and times of Lord Alfred the Gorilla’, in Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals, pp. 141–5.

5 Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals.

6 Rachel Poliquin, ‘Balto the dog’, in Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals, p. 94.

7 Stephen Howell (ed.), The Story of the Melbourne Cup: Australia’s Greatest Race, The Slattery Media Group, Docklands, Victoria, 2010.

8 Paddon, ‘Biological objects and mascotism’, p. 144.

9 Fiona McLean & Sam Cooke, ‘Constructing the identity of a nation: The tourist gaze at the Museum of Scotland, Tourism, Culture & Communication, vol. 4, no. 3, 2003, 153–62.

10 Susan A Crane (ed.), Museums and Memory, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 2000, p. 3.

11 John Harms, ‘Phar Lap: Ours then and now and always’, in Howell (ed.), The Story of the Melbourne Cup, p. 186.

12 Film Australia Digital Learning, Investigating National Treasures website, www.nationaltreasures.com.au/treasures/pharlap/, accessed 19 November 2011.

13 ‘Autopsy findings 9/4/1932’, transcript on National Museum of Australia file 90/163, Harry Telford collection.

14 Kathleen Kirsan, ‘Pocahontas and the large heart: X chromosome and sex linked genes’, Sport Horse Breeder, www.sport-horse-breeder.com/large-heart.html, accessed 9 November 2011.

15 Poliquin, ‘Balto the dog’, p. 107.

16 Jessica Owers, email communication, 27 October 2011.

17 ibid.

18 ‘Phar Lap’s heart’, Argus, 8 July 1932, p. 7.

19 Libby Robin, ‘Weird and wonderful: The first objects of the National Historical Collection’, in reCollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, volume 1, no. 2, recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_1_no_2/papers/weird_and_wonderful.

20 Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics, Routledge, Abingdon, 1995, p. 76.

21 National Museum Fast Facts, www.nma.gov.au/media/media-resources/national-museum-fast-facts, accessed 15 July 2012.

22 ‘Phar Lap’s skeleton’, The Argus, 24 February 1933, p.9.

23 Dryblower, ‘Phar Lap’, Sunday Times (Perth), Sunday 10 April 1932, p. 10.

24 Samuel JMM Alberti, ‘Maharajah the elephant’s journey: From nature to culture’, in Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals, p. 46.

25 ‘Phar Lap’s heart’, Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday June 4 1932, p.8.

26 ‘Phar Lap returns home’, Advocate, Saturday 17 December 1932, p.3.

27 Geoffrey N Swinney, ‘An afterword on afterlife’, in Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals, p. 221.

28 ‘Jumbo’s public career. His life and travels in Europe and America’, The New York Times, 17 September 1885.

29 Dave Madden, The Authentic Animal: Inside the Odd and Obsessive World of Taxidermy, St Martin’s Press, New York, 2011, pp. 40–1.

30 Transcript, Catalyst, Australian Broadcasting Commission, aired 19 June 2008, www.abc.net.au/catalyst/stories/2278343.htm, accessed 9 November 2011.

31 ‘Phar Lap’s skeleton: Preservation urged’, Geraldton Guardian and Express, 7 April 1932, p. 1.

32 ‘Skeleton of Phar Lap: For N.Z. museum’, Argus, 12 July 1937, p. 9.

33 Neil Clarkson, ‘Mighty Phar Lap’s skeletal makeover is complete’, Horsetalk, 14 March 2012, http://horsetalk.co.nz/2012/03/14/phar-laps-skeletal-makeover-is-complete/ accessed 7 February 2013.

34 Stu Piddington, ‘Phar Lap’s bones rattle horse fancier’, smh.com.au, August 8 2009, http://www.smh.com.au/national/phar-laps-bones-rattle-horse-fancier-20090807-eczd.html accessed 10 November 2011.

35 ‘Phar Lap’s skeleton to stand proud again’, The Age, October 21 2011, http://news.theage.com.au/breaking-news-world/phar-laps-skeleton-to-stand-proud-again-20111021-1max4.html accessed 10 November 2011.

36 Clarkson, ‘Mighty Phar Lap’s skeletal makeover’.

37 Michelle Henning, ‘Neurath’s whale’, in Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals, p. 157.

38 ‘Phar Lap dead’, Argus, 7 April 1932, p. 9.

39 Conclusions drawn from my own observations made while undertaking audience research at the ‘I love my place: Landmarks’ festival, Sunday 5 June 2011.

40 Amanda Lohrey, ‘The absent heart’, Monthly, June 2010, p. 48.

41 Harms, ‘Phar Lap’, p. 182.

42 Rachel Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing, Pennsylvania State University Press, Pennsylvania, 2012, pp. 22–3.

43 See Carole M Cusack & Justine Digance, ‘The Melbourne Cup: Australian identity and secular pilgrimage’, Sport in Society, vol. 12, no. 7, 876–89; Sophie Sunderland, ‘Post-secular nation; or how ‘Australian spirituality’ privileges a secular, white, Judaeo-Christian culture’, Transforming Cultures eJournal, vol. 2, no. 1, November 2007, http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/TfC/article/view/596, accessed 9 November 2011.

44 Mark Twain, The Wayward Tourist, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Victoria, 2006, p.60.

45 Cusack & Digance, ‘The Melbourne Cup’.

46Cusack & Digance, ‘The Melbourne Cup’ (p. 881).

47 ‘Melbourne Cup’, http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/melbourne-cup, accessed 7 February 2013.

48 Rod Fitzroy, ‘Introduction’, in Howell (ed.), The Story of the Melbourne Cup, p. 23.

49 John Harms, ‘Phar Lap’, pp.182–9.

50 Cusack & Digance, ‘The Melbourne Cup’.

51 AC Worthington, ‘National exuberance: A note on the Melbourne Cup effect in Australian stock returns’, Economic Papers: A Journal of Applied Economics and Policy, vol. 26, no. 2, 2007, pp. 170–9.

52 ‘At the museum’, in Phar Lap: Australia’s Wonder Horse, http://museumvictoria.com.au/pharlap/museum/index.asp, accessed 1 November 2011.

53 Cusack & Digance, ‘The Melbourne Cup’(p. 877).

54 Stephen Greenblatt, ‘Resonance and wonder’, Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 43, no. 4, January 1990, 11–34 (p. 28).

55 Cusack & Digance, ‘The Melbourne Cup’(p. 880).

56 Letter from Miss A Irwin to Harry Telford and David Davis, 6 April 1932, Museum Victoria, reg. no. HT13390.

57 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (2nd edn), Verso, London, 1991, p. 163.

58 Phar Lap before the Chariot of the Sun, Museum Victoria collection page, http://museumvictoria.com.au/collections/items/827225/print-j-l-fleury-phar-lap-before-the-chariot-of-the-sun-1932/, accessed 15 July 2012.

59 ‘The legend’, in Phar Lap: Australia’s Wonder Horse, http://museumvictoria.com.au/pharlap/legend/index.asp, accessed 11 November 2011.

60 Letter from Frances Black to Harry Telford, 8 April 1932, Museum Victoria, reg. no. HT13435.

61 Gallery Director, or This Way to Phar Lap, Museum Victoria collection page, http://museumvictoria.com.au/collections/items/1486450/christmas-card-eric-thake-gallery-director-or-this-way-to-pharlap-linocut-print-1954/, accessed 10 November 2011.

62 Richard Sutcliffe, Mike Rutherford & Jeanne Robinson, ‘Sir Roger the elephant’, in Alberti (ed.), The Afterlives of Animals, p. 65.

63 Swinney, ‘An afterword on afterlife’, p. 220.

64 Max Presnell, ‘Heart of a champion, heart of a nation’, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 April 2010, www.smh.com.au/sport/horseracing/heart-of-a-champion-heart-of-the-nation-20100410-rzrf.html, accessed 12 April 2010.

65 Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo, p. 163.