Abstract

In November 2004, the National Museum of Australia announced the acquisition of a collection from the Springfield property near Goulburn, New South Wales. Without doubt it is one of the most comprehensive and important collections of pastoral and domestic objects that the Museum has acquired. One of the intriguing objects in the collection was the family's medicine chest, dating from the family's earliest settlement in Australia. Research into the medicine chest resulted in two main lines of enquiry: the first, into the history of medicine and treatment in colonial Australia generally; the second, into the personal history of health, medicine and illness within a particular family.

____________________________________________________

First settled by William Pitt Faithfull in 1828, the estate, which became known as Springfield a decade later, grew over the generations to become a successful and profitable sheep stud. In 1844 Faithfull married Mary Deane who had migrated with her mother, sister, brother and nephew from Devon in England. The sisters had been teachers; soon after their arrival in Sydney in 1838, they established the Misses Deanes' school in Macquarie Place.[1] William had met Mary when he visited his nieces at the school.[2] His sister Alice married Andrew Gibson of Tirranna, a neighbouring property to Springfield.[3]

William and Mary had nine children: William Percy (known as Percy), George Ernest, Henry Montague (Monty), Reginald, Florence (Flory), Robert Lionel, Augustus Lucian (Lucian), Constance Mary (Concy) and Frances Lilian (Lilian).[4] They initially lived in a small stone cottage, but gradually more room was required to accommodate their growing family. In 1857, a large brick two-storey house was built with a three-storey square tower over the entrance. It was grand indeed, described by poet and man of letters Daniel Deniehy as 'a princely seat'.[5] When William Pitt Faithfull died in 1896, he left the family home, known as the 'Big House', to his two unmarried daughters Florence and Constance; but as Constance chose to live overseas, only Florence lived there.

Throughout Florence's many decades at Springfield, the house was not renovated, and she threw nothing away. Everything was kept just as it had been during her father's lifetime. When her niece Bobbie Maple-Brown (who had also been christened Florence) inherited the house in 1949, there was a vast number of historical objects to be managed. A large collection of papers was donated to the National Library of Australia, and some material was given to members of the extended family. But the majority of the objects remained at Springfield in two rooms set aside by Bobbie as a museum, with larger items in sheds and outhouses. Bobbie's children Jim Maple-Brown and Diana Boyd inherited Springfield and, with Jim's wife Pamela, were responsible for the donation of the collection to the National Museum of Australia.

The Museum was delighted with this substantial gift that spanned a large part of Australia's colonial history. The family was also pleased that the immense collection was being kept together. Family members assisted with the documentation and provided important contextual knowledge that had been handed down over the generations to help with the interpretation of the objects within a museum context.

When it arrived at the Museum in 2005, the material was formally divided into two parts. The Springfield merino stud collection comprises 170 objects relating to the pastoral property and the merino stud. The Faithfull family collection is much larger, comprising more than 3000 objects. Both collections relate to the social history of generations of the family who lived and worked on the sheep station for over 170 years. The objects, as described in a press release, range from 'an 1890s custom-built buggy to cricket trophies, wedding dresses, wool samples and a stuffed green parrot'.[6] Both collections have robust provenance, with objects supported by images and documents, some of them within the collection itself, others in the National Library of Australia's collection and elsewhere. The archive can help in the interpretation of the objects, either through recording their detail (including use) or providing some description, however brief.

The collection is one of the largest and most wide-ranging to have been gifted to the National Museum. Its potential to illustrate so many aspects of family life is huge. Its historical value is best summed up by the Museum's 'Statement of significance':

There is no other collection in the National Historical Collection [which makes up the bulk of the Museum's collections] to match the Springfield Collection in terms of diversity of material, temporal coverage, strength of provenance or relevance to the National Museum's collecting priorities. As a whole, the collection reflects issues identified in all of the Collecting Domains of the Museum's current Collection Development Framework, from 'Interaction with the Environment' (Collecting Domain No 1) to 'Building Australia' (Collecting Domain No 8). Individually, items in the collection will extend the National Historical Collection in themes as diverse as costume, surveying instruments, musical instruments, home medicine, horse-drawn carriages and wool growing.[7]

The condition of most of the items is very good. Indeed, the clothing is regarded as exceptional by the historians, textile conservators and curators who have viewed it. Items of clothing provide a tangible physical link to generations of the Faithfull family, both women and men. The process of dating these and linking them to their original owners required close collaboration. Museum staff, other experts in the textile and clothing fields, and the donors themselves all had input to the detailed documentation that is now recorded with the clothing and will be drawn upon for many more generations by museum staff, researchers and visitors. The experts believe that some of the clothing that belonged to Mary Deane's mother, dating from the late 1700s, is among the oldest in Australia.

The large number of objects from one family can now be used to illustrate themes and stories from different times over the last 170 years. These primary sources tell of values and attitudes, as well as fashions and links to the land. They extend far beyond Springfield, with letters and journals recording travels to and from other parts of the colony and abroad.

A medicine chest in the collection was the trigger for my research into the family and its experiences of medical training and serious illness. In itself, it is by no means unique or unusual. Museums, small and large, often include medicine chests in their collections. The Medical History Museum at the University of Melbourne has a fine collection, many of which were used by medical practitioners in Victoria and donated to the Medical Society of Victoria. The collection later came to the Australian Medical Association which donated them to the University in 1994.[8] There are also medicine chests in the Marks Hirschfeld Medical Museum at the University of Queensland and a small collection at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. These chests however, lack the rich provenance and associated family archive that give the Faithfull chest a place in history.

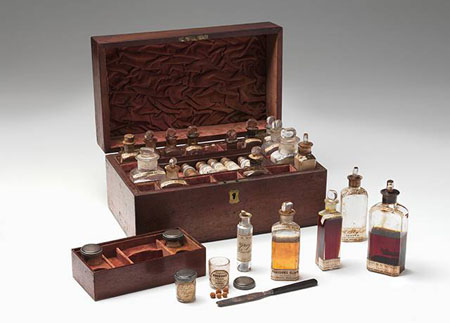

The Faithfull family medicine chest is a medium-sized timber box made of rosewood and mahogany, with two central lift-out trays.[9] It is 178 millimetres high, 350 millimetres long and 150 millimetres deep — the base about the size of an A4 sheet. There are 19 compartments, which are lined with velvet that has faded to an orange/coral colour. The lid has the same velvet lining, gathered to cushion and keep safe the heavy glass bottles containing powders and coloured liquids.

This is an English domestic medicine chest, made in large quantities from 1820 to about 1900, and in common use during that time.[10] Medicine chests could be purchased from chemists or by mail order and were advertised for the use of 'clergymen, private families, heads of schools and persons emigrating',[11] among others. They were expensive items: not every family could afford the luxury of a fitted chest. Opening the lid, you see the glass bottles in their compartments, eight along the back, seven at the front and two on each side. There are 18 bottles, mostly with glass stoppers, and one empty compartment. A central tray has four small jars with metal lids. Under this tray is a second central tray containing five smaller and thinner glass bottles, with cork stoppers, lying flat; and one narrow, black-handled palette knife used to extract powder from the larger bottles. This shallow tray would have originally contained scales and weights to accurately measure the compounds.[12] All the bottles, except one, bear the labels of Sydney chemist William Sloper. Some of these are also printed 'From Savory Moore & Co., London'. The exception is one bottle with the label 'W.H. Mutlow Chemist Armidale'.[13] The contents of the bottles are listed at Appendix A. The list of contents shows that some of the medicines could be used for minor complaints, such as mouth ulcers or coughs. Others were very much medicines of their time, used to induce vomiting, or purging of the bowels.

Knowledge of diseases and the ways in which they are treated have changed substantially in the last one hundred and sixty years. In the 1850s, antiseptic, preventative measures (other than for smallpox), sulpha drugs and antibiotics were miracles yet to be discovered.[14] Medicine was still considered as much an art as a profession. But often it was the knowledge that was passed down within the family, particularly in rural areas, that constituted day-to-day diagnosis and treatment. The Springfield chest provides a window onto the prevailing illnesses of the time and how they were managed in the absence of trained medical personnel.

The main objective of medical treatment at this time was to purge the body of acquired destructive manifestations and restore a healthy balance. Various means were employed, none pleasant. There were emetics for the stomach, purges for the bowel and methods to induce sweating. Other techniques included leeching, bloodletting, sometimes using a scarificator, and/or cupping.[15] These practices, it was believed, would let nature heal the body and restore it back to normal.

By the 1850s, germ theory was beginning to be understood.[16] For example, in 1854 John Snow investigated an outbreak of cholera in London and discovered the contagion originated from one water pump. When the pump handle was disconnected the cases of cholera decreased dramatically. It was however, still believed by many (including some medical practitioners) that sickness was caused by 'miasma' — a cloud of invisible deleterious forces, manifested by its bad smell, rising from the ground or from polluted waters. Disease could be a risk at every breath.

Before the nineteenth century, responsibility for keeping the family healthy and for treating sickness usually fell to the mother. This familial and female model of healthcare changed, in the Faithfull family and in Australia generally, during the nineteenth century, when medical care was increasingly professionalised, and women were initially prevented from studying medicine at university, despite their collective wisdom on health matters.[17]

Though not formally medically trained, the Springfield women recorded and compiled recipes for remedies for family ailments. Mary Faithfull used a hardback exercise book, with marbled covers and light brown binding, to record an assortment of intermingled recipes for food, medicines and household chores.[18] As well as recipes for bread, cakes, desserts and sauces, it includes proven family recipes for mixtures such as furniture polish, waterproofing for boots and 'a good ant destroyer'. There were also home remedies for various ailments, including for a sore mouth or throat, chilblains, a weak chest and a weak stomach. There are recipes for stomach elixir and a jelly for the weak. Some of these remedies made use of ingredients stored safely in the family medicine chest. Various drugs, which had to be carefully measured, some because of their potency, and others because of their noxious nature, were freely available from chemists.

The remedies that Mary Faithfull prepared would have been used in caring for her nine children, all of whom lived to be adults, which was no mean feat in this period when infant mortality was high.[19] Mary Faithfull, it seems, had the commonsense, expertise and family support to have successfully nurtured her children through their most vulnerable years. Very likely Mary's mother, who had successfully raised seven children, had passed on her knowledge, as some of the recipes in the family recipe book are written in her handwriting. Mary's sister Ann was also skilled in medicinal care: for example, her successful treatment of William Pitt Faithfull's toothache was recorded by Robert. In a letter to his father, Robert commented on his aunt's knowledge of medicine and that it was a pity Ann was not a doctor, because he would trust her when he was sick more than many doctors he knew.[20] The sisters' remedies and knowledge were also used in the care of the other members of the extended family, such as the Gibsons of Tirranna. There was also a sizeable population of resident employees at Springfield, who were joined at times by itinerant workers such as shearers. On isolated properties like Springfield, these home treatments were often the only first aid available, when a doctor could be up to half a day's or a day's ride away.[21]

The Faithfull family (and others) used family recipes for common ailments and to promote good health. They had the advantages of good food and clean living conditions, as well presumably as good genes: Mary and Ann lived into their 80s, and William Pitt Faithfull nearly made it to 90. The Springfield women also needed a source for the ingredients for their medicinal recipes. The first chemist to advertise in the Goulburn Herald was Mr CA Dibden, in 1851.[22] There were doctors in Goulburn from 1835 when Dr James Murray was appointed as first superintendent of Goulburn Hospital.[23] There were many doctors who followed with dispensaries. As Mary and Ann and their mother had lived in Sydney, it is likely the medicines were sourced there, but there is no information on medicines used prior to 1853, when William Sloper opened his shop. Chemists, then as now, place labels with their own name and address on each bottle. With careful use and small doses, was it possible that the original remedies in the medicine chest lasted Mary from her marriage until the chest was restocked in 1853?

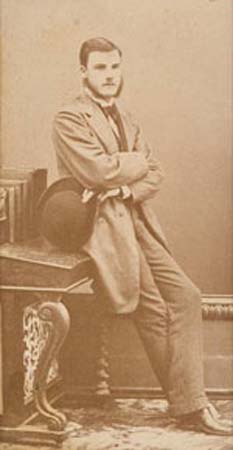

Robert Lionel Faithfull was born at Springfield in July 1853, the sixth child and fifth son of William Pitt and Mary Faithfull. Robert was first taught at home by his aunt Ann Deane. Later he attended Sydney Grammar School, which was then located in Randwick. He took a preliminary course in medicine 'to ascertain whether he felt capable of becoming a doctor'.[25] From August 1875 to June 1876, he studied at the Sydney Infirmary on Macquarie Street with Dr Andrew John Brady, an Irish physician and surgeon who had recently arrived in the colony. Brady was born in Ulster in 1849 and qualified in Ireland as a surgeon in 1872 and as a physician in 1874. In that year he arrived in Australia, registering in New South Wales. He found employment at the Sydney Infirmary where he was resident surgeon in 1875.[26]

Robert had been prompted to leave Australia as he wished to study homeopathy, and believed the American course was the best at that time. He could have followed a course in general medicine closer to home at Melbourne University, but not in Sydney. Although the medical school at Sydney University had been established in 1856, teaching did not commence until 1883.[27]

Robert Faithfull left Springfield for Goulburn on 22 August 1876, travelled by train to Sydney, and sailed on the SS City of Sydney three days later.[28] The ship took a month to reach San Francisco via Auckland and Honolulu. Robert then had a train journey of several days to reach New York. Travelling across America by train was potentially a hazardous journey in the 1870s, when Native Americans were still defending their land from the encroachment of the whites. As it happened, Robert's Native American encounters were 'peaceable ones'. He mentions the many young boys selling things 'they say the Indians made for which they ask large prices'.[29]

It did not take Robert long to discover that studying homeopathy would not qualify him to practise general medicine. Robert wanted to change his studies and wrote to his father for advice. His father raised no objections and Robert changed courses and attended lectures at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and Columbia College, later Columbia University. He reassured his father he had 'no intention or wish to give up Medical Study the more I study it the more I like it'.[30] By December 1877 he reported that: 'People say here I am born to be a doctor, and that is all very well, but believe me, you cannot be a doctor without study there is all ocean in front of me and time alone can work out the problems'.[31]

Robert wrote enthusiastically about his lectures. He was thrilled to be taught by some of the professors whose books had been recommended texts at the Homeopathic College. He detailed the lectures he attended and the doctors he met including: Professor Thomas on the diseases of women, Professor McLean for obstetrics, Dr Talrue for anatomy. He thought the lecturers were better at teaching science than those at the Homeopathic College and he would not miss the lectures and practical experiments of Professor Dalton 'for anything'.[32] Robert was also appreciative of the assistance of Dr Maigel, from St Luke's hospital, who invited him to visit and gave him cases to sound and diagnose. He said the experience was invaluable, as 'if you make any little error in diagnosis, why, you always have somebody to put you the right way. It is the little points that are so valuable to you to discriminate one chronic disease from another'.[33]

In successive letters Robert's faith in his ability increases. He writes with growing confidence shortly before his exams in February 1879: 'I am getting along famously and hope to pass well within a few days'.[34] Robert graduated from Columbia College in April 1879. He left for England to continue his studies and to take the examination at the Royal College of Physicians, which was required for registration in Australia. During a second sojourn in New York, in 1883, Robert gained experience in several hospitals and the Polyclinic where he studied the diseases of women. He observed many patients and he was also able to examine some, building his knowledge and expertise. In the letters covering this period, he expresses excitement about the latest advances in surgery, which had become safer as a result of antisepsis: 'Antiseptic surgery is the fashion of the day and the results here are very good ... Microscopy and Pathology are taking active strides here and have many workers, so you will see I am in an active and energetic field'.[35] These new sciences were enabling doctors to understand the previously invisible world of diseases and infections, finally eclipsing the theory of miasma.

The letters of Robert Faithfull in the National Museum of Australia depict vividly the experiences of a young Australian medical student living in New York, far from his home on the Goulburn Plains in New South Wales.[36] His letters are calm and focused, yet often upbeat, despite his admissions of homesickness.

Robert's interest in health matters is clear from his correspondence. In one of his first letters written from New York, in 1876, he had already moved from his hotel to lodgings in central Manhattan, at 43 West 24th Street. His room was at the back of the house, which he had chosen for the morning sun. He noted that the backyards were not like those 'of Sydney where everything is thrown out, but are merely used as drying yards and places for children to play in'.[37] When he wrote to his aunt Ann a month later, he confided how much he had cried when he had received a letter from his mother but he was very well despite the homesickness, 'and as happy as circumstances will permit'.[38] Alone in New York, he said he had not made any particular friends among his fellow students and wrote of the cold weather. He would have liked the companionship of his brother Reginald.

Robert wrote in great detail about his travels, though he said little about the city of New York. He was more interested in the seeds, grasses and livestock he observed at the Staten Island farm of the Cameron family, who had befriended him. His letters also express an almost constant homesickness. Writing weekly, he kept in close contact with his family and home, despite the length of time it took letters from New York to reach Goulburn and return. His letters also give the reader an understanding of his strong Christian faith. He emerges as a sober, hard-working and somewhat lonely student in his first years. His correspondence leaves no doubt that he was there to study and that his end goal was always to return to his family in Australia as a well-qualified doctor.

In 1880 Robert received worrying news from the family: his brother Reginald had developed tuberculosis. Late in the year he returned to Springfield to look after his brother, hoping that his qualifications and expertise would help Reginald to regain his health.

Prior to his illness, Reginald Faithfull played a prominent role in managing his family's properties at Springfield and Brewarranna, near Narrandera, New South Wales. His decline due to tuberculosis provides a glimpse into a documented case of illness in the family, and explores the part that various members, particularly Robert Faithfull, played in the patient's care. It is a study of life, illness, death and mourning in a wealthy colonial family in New South Wales in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Reginald kept work diaries from 1868, when he was 18, until 1880, when he was 30 and diagnosed with tuberculosis. These diaries are held by the National Library of Australia, as part of the Faithfull family papers.[39] Unlike Robert's lengthy letters from New York, Reginald's daily entries are seldom more than one line, and often just a few words, that document the daily tasks in a matter-of-fact way. For 12 years, he chronicles his management of the Springfield property and the work he undertook and supervised there. From them, it is possible to reconstruct what his life on the station was like while his brother studied in New York. Other sources include William Faithfull's diaries, also held at the National Library, and letters written by Faithfull family members that are in the National Museum's collections.[40]

Reginald documents the comings and goings of the men of the family: 'Monty left for Sydney', 'Percy came home', 'Papa went to Goulburn'.[41] The activities of the women are seldom mentioned, except when Reginald provided the transport: 'In Goulburn with Concy and Flory', 'Took the ladies to Lake Bathurst'.[42] 'Aunty' (Ann) is mentioned a few times: a visit to Mrs Cox in Goulburn, or giving an ill worker a blanket. Reginald recorded on 4 April 1869: 'Aunty saw Sam, gave him a blanket'. Possibly Sam was one of his workmen she visited. His mother is hardly mentioned. Her relative absence from Reginald's daily records might reflect her preoccupations with the family home, her days filled with household tasks and teaching her younger children. In this respect Reginald's work diaries indicate a separation of the male and female worlds.

In the diaries, Reginald comes across as hardworking and conscientious. He documents the names of the men who worked at Springfield, and the daily tasks carried out according to the seasons, such as ploughing, sowing, hilling, hoeing, reaping and cutting hay with a machine. He killed a bullock every two weeks or so for rations. Shearing was a large operation, in some years taking over a month. In 1876 he records employing 15 shearers.[43] As one would expect from someone living on the land, Reginald comments on the weather: he seemed to feel the cold and wet more than the heat, as hot weather is rarely mentioned. Perhaps he was susceptible to the cold and damp and early on harboured the disease that would kill him.

In July 1880, Reginald recorded that he was 'off to Sydney to see Dr Fischer about my cough.' He may first have visited a doctor in Goulburn before travelling to Sydney to see Robert's friend, the well-qualified Dr Fischer.[44] The family had many links with Sydney: Mary and Ann had taught there and Reginald's brothers Monty and Percy were living there. William Pitt Faithfull travelled to Sydney regularly for business and sometimes his wife and daughters accompanied him for a change of scene and to participate in Sydney society.

Like many other healthy young adults of the time, Reginald had developed pulmonary tuberculosis — also named phthisis, consumption or the 'white plague' (as opposed to the bubonic , or 'black' plague). Until the advent of antibiotics in the 1940s, very little could be done. Pulmonary tuberculosis has been described as 'the most destructive of the top seven killer diseases in New South Wales and Victoria between 1880 and 1900'.[45] Tuberculosis is spread by coughing and sneezing. Dried sputum from tuberculosis victims can last for months in a room and can be inhaled or ingested as dust. Tuberculosis can attack any part of the body but is most often seen in the lungs. The symptoms are coughing, high temperature with night sweats, and emaciation. Untreated, lung tissue is gradually destroyed, starting with a small patch and increasing until the whole lung is diseased and large amounts of phlegm and blood — from inflamed blood vessels in the lungs ruptured by coughing — are coughed up.

Treatment at the time consisted of consuming a diet high in fat, with lots of butter, cream and cheese; rest; and light exercise, consisting of walks, preferably up a slight incline.[46] Many of the medicines in the Faithfull chest could have been used to treat the symptoms of consumption.[47] None of those believed to be beneficial at the time are used today. Some are considered harmful; others, useless.

In the eyes of his family, Robert's training had made him supremely qualified to care for his brother. Robert himself was sure he would be able to help. The summer was spent at home; but as winter approached, the climate at Brewarranna station was deemed better for a consumptive than that of Springfield. The two brothers left Springfield on 6 April 1881, and the next day caught the train from Goulburn to Narrandera, on their way to Brewarranna.

In the 1880s, Brewarranna, on the banks of the Murrumbidgee River, was described as 'a compact run with long frontages, excellent red gum flats, extensive swampy plains of tall spike rush and shady pine ridges to which stock might escape during the floods'.[48] The land had improved since Reginald had reported in 1877 that cattle were dying in the drought and the property should be fenced to stop neighbours' stock straying onto the land, where there was good access to water, but there were few of the props of a civilised life or the good food of home. The station was isolated and in a fairly remote area. It does not seem though that Reginald was sent there to isolate him from his family, as he received visits from his cousin Edgar and all the brothers, except Percy who stayed at Springfield to ease the anxiety there. It was more likely it was chosen for the climate, a change of air being commonly perceived to be beneficial to health. Robert and Reginald planned to return to Springfield once the weather was warmer.

Robert's letters kept the family abreast of the status of his patient. However, they contain little information on treatment and few of the personal observations that enliven Robert's letters from America. He asked his father to tell his mother not to fret as there was enough pressure already. He reiterated, 'We will do all we can and leave the rest in God's hands'.[49]

The summer was spent with the family at Springfield, and Robert and Reginald returned to Brewarranna in April 1882. The optimism of a year earlier, 'that Reginald will get round in time if he goes on as well as he appears to be doing now', was replaced by sorrow and distress as Reginald grew weaker and his death seemed inevitable.[50] Robert, still only 28, warned the family. He was not afraid to tell the truth. He wrote to his aunt that he had told Reginald he thought there was little hope of him recovering: 'He took it very quietly and said he thought sometimes he would get over it, and at others he could not'.[51]

The last letter from Robert at Brewarranna was to his aunt Ann Deane, dated twice, the 20 May 1882 and also 3 June, just six days before Reginald's death. Edgar and all the brothers except Percy were with Reginald when he died. They took two-hour shifts, keeping watch and waking Robert if he was needed. Robert relayed to the family at Springfield Reginald's wish that no one from home should visit him, as their presence would make him more anxious. Robert was glad Constance was not there as it would be too much for her to bear. A letter dated 30 May 1882, from Percy at Springfield to Edgar at Brewarranna, shows the dread anticipation at Springfield, especially of their mother, in the last days, as Reginald deteriorated, rallied slightly, then sank. Percy wrote that he dearly wished to see and hear Reginald once more, but he was glad he was able to support the family at Springfield to 'sometimes to be less despairing than they would have been else'.[52] Their mother, Mary Faithfull, was almost out of her mind with worry and despair, and Percy urged Edgar not to delay in returning to Springfield 'should the worst still happen', as their mother, one evening, had believed that none of them would return.[53] She had become hysterical and no one was able to calm her. He ended the letter with the hope for a miracle: 'we trust that you all with Robert by Permission of God may accomplish such a miracle as seems to us hardly less than the raising of Lazarus'.[54] Robert's faith was still strong. For him, the outcome rested with God, but there was no talk of a miracle. He simply wrote, 'May "God" comfort you all in your great sorrow and help you all to bear it bravely, gladly would I send you comfort, but I am unable to do so'.[55]

Reginald Faithfull died on 9 June 1882. His brothers returned with his remains to Springfield, where he was buried five days later in the family cemetery. William Pitt Faithfull noted on that day: 'My darling Son buried in the Sepulchre. The spot on which it is built was chosen by himself whilst in strong and perfect health'.[56]

A one-page undated document, titled 'Reginald's last wishes', is signed by Montague (Monty) Faithfull and George Faithfull. It mainly gives directions about Reginald's dearest possessions: his horses. He names his most prized: 'I desire that father shall have Sportsman to take care of and that nobody is to ride him. Edgar is to have Rushlight and her Ajax foal. My old grey mare is not to be allowed to die of poverty but to be shot this winter if necessary'.[57] The rest of his stock was to be sold. Percy and Robert were to receive £100 each, as well as one-twelfth of his estate along with the other members of his family, 'for the purpose of obtaining some token in remembrance of me'.[58]

Robert stayed in Australia for over a year after Reginald's death and left Sydney in October 1883, on his way to New York via San Francisco, to resume his studies. In Manhattan, he lived at 34 West 21st Street, a few streets from his previous lodgings. Robert finally returned to Australia in 1884, an experienced and well-qualified doctor. He was an MD and also a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, London, and a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians, London.[59] He would not have been able to gain such wide experience or qualifications in Australia.

Through the portal of the medicine chest various medical aspects of medical history have been featured in this paper, aspects that could provide the basis for a fascinating museum display on personal experiences of medicine in the 19th century. Had a different object been chosen, the view would have been through a different portal and given us a different angle and reflection.[60]

The Springfield collections are a rich source of material items for display, including household items of all sizes, shearing gear, clothing, portraits, farm ledgers, letters and diaries. Images of the family and of Springfield set the scene and conjure a different time. Similarly the letters tell poignant stories of a homesick medical student and later, an ailing son and brother. The diaries of Reginald and William Faithfull document the weather, the seasons and daily occupations, giving context to the land and its management. The Faithfulls worked hard at improving Springfield and Springfield was good to them. Despite times of drought and occasional flood, they had good judgement and the crops and the sheep did well. Springfield was more than a station that provided for the family. There was a deep attachment to place, and also to each other in that place.

The material drawn on for display can be divided into five types with different functions. All can convey messages:

- In the archives, the letters and diaries can disclose the personality of the writer.

- Newspapers impart the formal notices as well as the preoccupations of the day.

- Business and farm ledgers reveal important legal, monetary or agricultural details.

- The photographs and portraits offer stiff snapshots in time, an exterior view without revealing the inner person.

- The clothing and textiles help to put together a more three-dimensional, material picture of the owner and by extension, the family. For example, a pink merino dress displays the owner's fashion sense and the family's wealth and status.

In this way, and through this store of objects and papers, an exhibition with the medicine chest as the central object can illustrate the rich strands of the family and colonial histories. The chest is the starting point and also the end point: opening the box leads to the rich archive that reveals aspects of a family, their feelings, joys, fears and a family tragedy.

The medicine chest is an attractive object of wood, glass, velvet, powders and coloured liquids. We have come to know the family and some of their ailments through documented remedies and the medicines that were stocked in the chest. We can be sure of a number of stories relating to the chest, others we can assume, or speculate. It has had a number of lives and known four generations of one family. It is part of the history of medicine, and it is now destined for public display and museological interpretation. It cannot speak but it is here to tell a significant tale.

What has changed over the years? Medical science has provided the means of protection from fatal childhood diseases through immunisation, but the memories of deaths from measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases are fading in the developed world and the uptake of these preventative measures has declined. The miracle cure of antibiotics has been over-prescribed and there is increasing prevalence of multi-resistant bacteria that antibiotics no longer work against.[61] There can be no question that there have been great bounds in surgery. Sometimes it is tempting to turn back the clock, to times that are perceived as more simple and peaceful but not in the realm of medicine. The lack of medical knowledge, the use of poisons and ignorance of sanitary measures made surviving colonial life a risky business. There was nothing in the chest to cure Reginald.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

Appendix

Drugs in the Springfield medicine chest

| No. | Name | Made from | Treatment for/used as | 'Directions for using the medicines contained in the chest'[62] | Modern equivalents | |

| 1 | Tincture of myrrh[63] | stem of Commiphora molmol and other species | mouth ulcers: apply direct or as mouth wash | 'In diseases of the teeth and gums, arising from scurvy, or a dissolved state of the blood, this makes a useful wash for the mouth.' | mouthwashes | |

| 2 | Grey powder | mercury and chalk | laxative for adults, laxative while teething for children, syphilis | Not listed. |

senna or psyllium antibiotics for syphilis |

|

| 3 | Sweet spirits of nitre | alcoholic solution of nitrous ether | angina, diaphoretic to promote perspiration in colds and flu (opened bottles should not be kept longer than 7 weeks) | 'It gives great relief in suppression and heat of urine, particularly in the scalding arising from gonorrhoea, or clap: the dose, from three to twenty grains dissolved in barley-water, or any other convenient fluid.'[64] |

nitrites relaxants |

|

| 4 | Paregoric elixir | tincture of opium, benzoic acid, camphor and anise oil | expectorant in cough mixture | 'For coughs and colds, a tea-spoonful or two may be taken every night going to bed in a cupful of warm barley-water, whey or any herb tea.' | cough mixture with expectorant | |

|

5 |

Laudanum | tincture of opium | analgesic, for diarrhoea and gut and kidney problems (intestinal biliary and renal colic) |

'Opium in the form of laudanum, or in pills of one or two grains, valuable as a medicine to induce sleep, or give relief in any severe pain; not to be given in any inflammatory complaints, nor in the early stages of dysentery.' | paracetamol, codeine; loperamide for diarrhoea | |

| 6 | Ipecacuanha | dried root or rhizome of Cephaelis ipecacuanha | expectorant, to induce vomiting and diarrhoea | 'An emetic of ipecacuanha is useful in asthmatic complaints, shortness of breath, and in looseness and weakness of the bowels. Thirty grains are a proper dose for a grown person.' | used until recently — last 7–10 years as an emetic; poisons are now absorbed rather than vomited | |

| 7 | Compound chalk powder | calcium carbonate | absorbent and antacid used for indigestion and diarrhoea |

Not listed. Prepared chalk is listed. | loperamide | |

| 8 | Spirit of sal volatile | ammonium bicarbonate with lemon oil, nutmeg and alcohol | restorative in fainting or collapse (smelling salts similar) | 'In lowness of spirits, pains in the stomach, or rheumatic complaints, thirty drops are to be taken two or three times a day in a wine-glass of peppermint water.' | no contemporary equivalent | |

| 9 | Sulphuric ether | solvent for oils, resins, cleaning skin prior to surgery and removing adhesive plaster from skin | Not listed.[65] | antiseptic solutions | ||

| 10 | Compound tincture of bark | chinchona bark percolated with alcohol, with dried bitter orange, cochineal added | astringent properties, a bitter to stimulate appetite; source of quinine alkaloids (Corrosive solutions which neutralise strong acids) | Decoction of bark listed.[66] | Chloroquine (anti–malarial drug) | |

| 11 | Fryar's (or Friar's) balsam | resin from incised stem of styrax benzoin with aloes and balsam of tolu in alcohol | used internally in chronic bronchitis and externally as an inhalation in steaming water for bronchitis and laryngitis, and as an antiseptic and styptic (stops bleeding) (contracts organic tissue) to treat cuts | 'This is a proper application for cuts and fresh wounds moisten some lint in it which is to be applied to the wound but if there should be much pain, with inflammation, it should be poulticed with a bread and milk and sweet oil poultice, twice a day, until these symptoms are removed.' |

antibiotics; expectorants pressure bandages to stop bleeding. | |

| 12 | Powdered rhubarb | dried rhizome of Rheum palmatum | purgative, used in many proprietary medicines sold as aperients | 'This is a mild purgative in weak and delicate habits. It is also a proper medicine in costiveness, indigestion from crudities, cholic, gripings, and pains in the bowels; the dose is from ten to forty grains for a grown person, ten grains for a child of two years old.' | prune juice; polyethylene glycol | |

| 13 | Essence of peppermint | distillation of Mentha piperita flowering tops | carminative (helps to expel wind); purgative preparations to prevent griping | 'The use of this medicine is to prepare peppermint-water. The quantity of this essence is one tea-spoonful to half a pint of water, which makes the common peppermint-water of the apothecaries shops.' | peppermint | |

| 14 | Elixir of vitriol | sulphuric acid 7% in alcohol, tincture of ginger and spirits of cinnamon added | astringent in treating diarrhoea and cholera | 'A medicine of very considerable importance. A wine-glass full of water as acid as the person can bear taken occasionally, followed by frequent draughts of cold water for bleeding from the stomach, lungs or nose. Dose from ten to fifty drops twice or thrice a day.' | rehydration salts; gastric treatments | |

| 15 | Antimonial wine | antimony potassium tartrate dissolved in water and added to sherry-type wine | emetic, used also to treat various infestations of tropical internal worms | 'Is an useful medicine in cases where perspiration is required, or in slight fever, with cold: give thirty to forty drops in a little warm gruel.' | vermifuge medicines or agents (to expel parasitic worms) | |

| 16 | Pure condensed magnesia | salts of magnesium, such as carbonate of oxide; powder is likely to be the heavy form | antacids, for treating gastric hyperacidity and peptic ulcer, mildly laxative | 'Magnesia alba — for the heart-burn, or acidities of the stomach, a tea-spoonful or two may be taken occasionally in a wine-glass of peppermint water. In griping and complaints of the bowels of infants, attended with green or curdled stools mix magnesia with peppermint water. Removes costiveness in women with child.' |

antibiotic ulcer treatments H2 antagonists for hyperacidity | |

| 17 | Tincture of rhubarb | percolation of rhubarb, cardamom seed and coriander | used in mixtures as an astringent bitter and mild laxative for infants | 'In disorders of the stomach and bowels, from crude and indigestible food, flatulencies, unripe fruit, &c, this is a proper medicine, taken to the quantity of one or two table-spoonful, in a glass of peppermint water.' |

psyllium prune juice milk of magnesia and other antacid treatments | |

| 18 | Antibilious pills | 'after dinner pills'; aloes, ginger, rhubarb, soap | aperient (mild purgative) | 'These pills will be found an excellent purge in all diseases unattended with fever, where purging is necessary they speedily remove bilious complaints, loaded bowels, indigestion and oppression of the stomach these may be given with advantage in the cold stage of Ague, in conjunction with opium or laudanum.' | purging not necessary | |

| 19 | Blister plasters | external application of ointment on leather or linen on the site of internal pains or inflammation | Blistering ointment. | treat internal condition | ||

| 20 | Blue pill | pill of metallic mercury finely dispersed in syrup | syphilis | Listed as treatment for Lues venerea (syphilis) but not in index. | antibiotics | |

| 21 | Compound rhubarb pills | indigestion, pain in the stomach | Not listed. |

prune juice polyethylene glycol | ||

| 22 | Grey powder | mercury and chalk (duplicate) | laxative, for teething and for syphilis | Not listed. |

prune juice paracetamol for infants antibiotics for syphilis | |

| 23 | Calomel | mercuric chloride | purgative and sedative, useful in dysentery and cholera | 'This is an active purge and a good vermifuge but requires proper medical advice in administering it: two or three grains are a dose for children two to six, eight or ten years of age; and four or five grains are generally considered as a proper dose for a grown person.'[67] | antibiotics but not for cholera (makes worse) | |

| 24 | Tartar emetic | antimony potassium tartrate | small doses as expectorant, larger doses as emetic; also to treat venereal disease | 'In all diseases accompanied with fever, where unloading and cleansing the stomach is necessary, or where an active vomit is required, this is the most proper emetic.' |

H2 antagonist for over-indulgence antibiotic for venereal disease | |

| 25 | James' powder | antimony trioxide, calcium phosphate | expectorant, diaphoretic | 'Useful in fevers, colds and rheumatism. In colds five or six grains taken on going to bed, will, in most cases be very serviceable, especially if it brings on perspiration if it vomits or purges the quantity must be lessened.' | paracetamol | |

| 26 | Dover's powder | opium and ipecacuanha | diaphoretic, anodyne, gastric ulceration, dyspeptic vomiting, diarrhoea | 'Of ipecacuanha, used in dysentery, fluxes, and rheumatism; it is likewise a valuable medicine for bringing on perspiration in colds, coughs, &c. the dose is ten grains in any weak liquor.' | paracetamol; loperamide; antibiotics |

The following abbreviations are used: NLA (National Library of Australia), NMA (National Museum of Australia); RLF (Robert Lionel Faithfull), WPF (William Pitt Faithfull), MF (Mary Faithfull).

1 Advertisement for the school dated September 1838, by Sydney printer James Tegg, Faithfull Family papers, National Library of Australia (henceforth NLA), MS 1146, Box 38.

2 C Crilly, 'Settlers and settling in', Friends of the National Museum Magazine, September 2006, p. 12.1 Advertisement for the school dated September 1838, by Sydney printer James Tegg, Faithfull Family papers, National Library of Australia (henceforth NLA), MS 1146, Box 38.

3 Another prized collection object, the Tirranna Picnic Race Club Challenge Cup, is another link. It was awarded for the main race at the Tirranna Picnic Races held on the Gibson property, and jointly organised by members of the Faithfull and Gibson families.

4 Mary and William's children were William (1844–1924), George (1846–1910), Henry (1848–1908), Reginald (1850–1882), Florence (1851–1949), Robert (1853–1930), Augustus Lucian (1855–1947), Constance (1857–1939), Frances (1859–1948). Family tree from John Faithfull.

5 EA Martin, The Life and Speeches of Daniel Henry Deniehy, Melbourne, 1884, p. 9.

6 'Huge pastoral gift to National Museum', NMA media release, 6 November 2004, www.nma.gov.au/media/media_releases_index/2004_11_06.

7 'Statement of significance for the Springfield collection', National Museum of Australia (henceforth NMA). The National Historical Collection 'is the Museum's core heritage collection representing Australian History and experience. It is a selective and representative collection that seeks to document the breadth of national life the highest thresholds are applied in establishing object significance for the National Historical Collection', NMA Collections Development Framework.

8 Information on the medicine chest collection from Ann Brothers, curator (to 2008) of the Medical History Museum in the Johnstone-Need Medical History Unit, University of Melbourne.

9 Medicine chest NMA 2005.0005.0223. Measurements: 180 x 350 x 150 mm. Research on timber conducted by National Museum of Australia conservation department, 2007.

10 Dr Ted Kremer, pers. comm., April 2006.

11 Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, A9245-68: Thomas Keating, Chemist, The Companion to the Medicine Chest, Containing Instructions for the Treatment of those Disorders which Most Commonly Occur; with Directions for Using the Medicine Applicable to Them, 3rd edn, Gilbert & Piper, London, 1836.

12 The location of the scales and weights, why they were discarded and how they were lost are no longer known.

13 Armidale is a town several hundred kilometres north of Goulburn, on the New England Tableland. Other than the presence of this bottle, no evidence of a visit to Armidale by a member of the family has been found.

14 The sulpha drug sulphanilamide and its derivatives, used extensively in the chemotherapy of bacterial infections. The first sulphonamide was prontosil, originally prepared by Gerhard Domagk (1895–1964), see AS MacNalty (ed.), Butterworths Medical Dictionary, Butterworths, London, 1965, pp. 1373, 1166.

15 A scarificator is an instrument used in scarifying (making a number of small punctures or incisions in the superficial layer of the skin) comprising a series of small concealed lancet points which may be brought into action by pressure on a trigger: MacNalty, Butterworths, p. 1272. Cupping uses a cup-shaped vessel in which a partial vacuum is produced so that, when applied to the skin over a part, a swelling with hyperaemia [an excess of blood] forms: MacNalty, Butterworths, p. 373.

16 Alexander Gordon, in his Treatise on Puerperal Fever of Aberdeen (1795) reasoned that the fever was spread by the doctor or midwife. John Snow in 1854 argued that cholera was spread by contaminated drinking water, not miasma. During a London cholera epidemic, he had the handle removed from a local water pump and the sudden decrease in the number of cases confirmed his theory: R Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present, Fontana Press, Harper Collins, London, 1999, pp. 369, 413.

17 It was not until 1885 that Sydney University, in the face of fierce opposition, admitted its first female medical student. Despite the opposition of the dean, 'who publicly voiced his opposition to women in medicine', and the vice-chancellor, who declared that no woman would graduate in medicine while he was in the job, Dagmar Berne enrolled that year as the university's first, and only, woman medical student. In the face of such opposition, Berne decided to complete her degree overseas. She studied in London and Scotland and returned a qualified doctor, becoming the second woman to register in New South Wales. The first, (Emma) Constance Stone, studied in America after being refused entry to Melbourne University, and was registered in New South Wales in 1890. See http://sydney.edu.au/senate/documents/History/Dagmar.pdf, accessed 2009; P Russell, 'Stone, Emma Constance (1856–1902)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 12, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1990, pp. 98–100.

18 Recipe book, NMA 2005.0005.0930.

19 Pat Jalland records that 'in the 1880s about 90 per cent [of children] might live to twelve months, 82 per cent to 5 years, and only 78 per cent became adults', Australian Ways of Death: A Social and Cultural History 1840–1918, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2002, p. 69.

20 Letter, RLF to WPF, 12 July 1881, NMA, IR 4459.0162.

21 S Mossman & T Bannister (1853), quoted in Philippa Martyr, Paradise of Quacks, Macleay Press, Sydney, p. 64. Many other writers also comment on the delay in a doctor attending the sick or injured.

22 S Tazewell, 'The story of Goulburn pharmacies', in Goulburn and District Historical Society Bulletin, July 1985, no. 194, pp. 2–3.

23 AJ Proust (ed.), History of Medicine in Canberra and Queanbeyan and their Hospitals, Brolga Press Pty Ltd, Gundaroo, NSW, 1994, p. 4. Proust notes that there is no further record of Murray's medical practice.

24 M Franklin, Childhood at Brindabella, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1963; M Gilmore, Old Days, Old Ways, Angus & Robertston, Sydney, 1934; Gilmore, More Recollections, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1935.

25 WPF diary entry 31 July 1875, NLA, MS 1146, Box 19.

26 Geelong Hospital Library, Australian Medical Pioneers Index, www.medicalpioneers.com/cgi-bin/index.cgi?detail=1&id=1961, accessed 14 April 2008.

27 History of Sydney University Medical School, medfac.usyd.edu.au/about/history/index.php, accessed 8 June 2008.

28 WPF diary entry 1876, NLA, MS 1146, Box 19.

29 RLF to MF, 18 October 1876, NMA, IR 4125.0039.

30 RLF to WPF, 1 January 1877, NMA, IR 4459.0150.

31 RLF to MF, 22 December 1877, NMA, IR 4459.0049.

32 RLF toWPF, 15 January 1877, NMA, IR 4459.0170.

33 RLF to MF, 16 December 1877, NMA, IR 4459.0050.

34 RLF to MF, 8 February 1879, NMA, IR 4459.0104.

35 RLF to MF, 23 December 1883, NMA, IR 4425.0121. IR

4459.0121

36 Robert Faithfull collection NMA, IR 4459 and Faithfull Family collection NMA 2005.0005. Robert Faithfull letters collection NMA, IR 4125.

37 RLF to MF, 18 October 1876, NMA, IR 4125.0039.

38 RLF to Ann Deane 25 November 1876, NMA, IR 4459.0042.

39 Faithfull family papers, NLA, MS 1146.

40 Robert Faithfull collection, NMA, IR 4459.

41 Reginald Faithfull diary entries, 19 August 1869, 21 January 1872, 1 October 1868, NLA, MS1146, Box 21.

42 Reginald Faithfull diary entries, 5 February 1879, NLA, MS1146, Box 22; 20 March 1875, NLA, MS1146, Box 21.

43 Reginald Faithfull diary entry, 6 November 1876, NLA, MS 1146, Box 22.

44 Robert recommended Dr Fischer who had qualifications from New York and London and was also versed in homeopathy.

45 FB Smith, 'The first health transition in Australia 1880–1910', quoted in Jalland, Australian Ways of Death, p. 54.

46 Professor Barry Smith, pers. comm., March 2008.

47 Drugs and their uses compiled from information from Geoff Miller, pharmacy historian and Mrs Isabella Beeton, 'The doctor', in Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, Chancellor Press, London, 1982 [1861], Chapter 43: The Doctor. Remedies included myrrh for a sore throat and mouth, calomel to relieve fever, compound tincture of bark to stimulate appetite, Dover's powder for dyspepsia and diarrhoea, opium to allay pain. Laudanum, which also contained opium, was used as an analgesic and to treat diarrhoea. Essence of peppermint would relieve gastric colic and flatulence, elixir of vitriol also used to treat diarrhoea. Tartar emetic, James' powder, ipecacuanha and paregoric elixir were all used as expectorants to aid the removal of bronchial secretions. Fryar's balsam was taken for bronchitis and also used as an inhalation.

48 Bill Gammage, Narrandera Shire, Griffin Press, Netley SA, 1986, p. 82.

49 RLF to WPF, 15 November 1881, NMA, IR 4459.0072.

50 RLF to WPF, 15 April 1881, NMA, IR 4459.0067.

51 RLF to Ann Deane, 20 May and 3 June 1882, NMA, IR 4459.0144.

52 William Percy at Springfield to Edgar at Brewarranna, 30 May 1882, NMA, IR 4459.0127.

53 ibid.

54 ibid.

55 RLF to Ann Deane, dated both 20 May and Saturday 3 June 1882, NMA, IR 4459.0144.

56 WPF diary entry NLA, MS1146.

57 'Reginald's last wishes', NMA, 2005.0005.1435.069. The 12 are his eight siblings, his parents, aunt Ann Deane and cousin Edgar.

58 ibid.

59 RLF Medical Certificates: NMA, IR 4459.0019, 0021, 0022 and 0024.

60 Research on other members of this large extended family should reveal other stories of family life. The women's stories are likely to be especially interesting: Florence, who lived to be nearly 100 and left Springfield for only short periods; her sister Constance, who travelled and lived overseas; Ann Deane, who taught and cared for her nieces and nephews; Mary, who bore nine children in 15 years at Springfield. William Pitt Faithfull's story is also interesting: a successful and innovative landowner and sheep breeder, he had a reputation as a clever and hard-headed businessman, but his diaries reveal his fatherly pride and affection for his children.

61 'Antibiotic resistance', www.healthinsite.gov.au/topics/Antibiotic_Resistance, accessed November 2010; A Zumla, 'The white plague returns to London', Lancet, vol. 377, no. 9759, 1 January 2011, 10–11.

62 This column is derived from a set of directions that accompanies a comparable medicine chest in the collection of the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, entitled: 'Directions for using the medicines contained in the chest', W Brydon & Co., Wholesale Druggists, London, 1836.

63 A tincture is 'an alcoholic extract of a vegetable or animal drug prepared usually by a percolation or maceration process. The strength is usually such that ten parts by volume of tincture contains the active constituents of one part by weight of the dry drug', Butterworths Medical Dictionary.

64 A grain is the smallest unit of weight in most imperial systems, originally determined by the weight of a plump grain of wheat.

65 Sulphur: 'used internally as a mild intestinal antiseptic or stimulant, externally as an antiseptic and parasiticide', Butterworths Medical Dictionary.

66 A decoction is an extract of the water-soluble substances in a drug made by boiling it for 10 minutes in distilled water. Decoctions are best prepared fresh but concentrated decoctions are made usually to be diluted 1 to 7. Alcohol must be added to concentrated decoctions to a strength of at least 20 per cent in order to preserve them.

67 Five grains of calomel contains 300 mg of mercuric chloride. A fatal dose has been calculated at 1000 mg: Martyr, Paradise of Quacks, p. 36.