review by Grace Karskens

A friend of mine had been visiting exhibitions about city histories around Australia. 'When I saw The Melbourne Story', she told me, 'I almost cried'. What on earth elicited such a response? Mostly relief, she said, and a flash of joy. Here at last she found an exhibition about an Australian city which is tied together by narrative: it actually tells a story of Melbourne.

Anthropologist Julie Marcus probably knows what my friend means. Marcus argues that the true genius of museums lies in the flash of understanding when something is explained. It makes them sexy in a way that displays of random, unconnected things-for-their-own-sake cannot, however beautiful or hi-tech the presentation.[1] So serious history, with which the city of Melbourne is so richly endowed, was evidently taken seriously here. It is treated as core business, harnessed for structure and interpretation, rather than being regarded with suspicion and avoided. Nor has this approach resulted in the dreaded 'book on the wall'. A cornucopia of things tell the story in ways words alone can never do, but it is history — broader historical narratives, insights, links, smaller contextual stories and yes, text — which unlocks them, and allows them to speak.

It is this narrative thread that makes it possible for visitors to engage meaningfully at many levels and in different ways with this exhibition — surely among the most difficult, yet essential, challenges museums face. Thus, as a historian of Sydney, I can be struck by both the divergences and surprising similarities between early Melbourne and its older cousin up north; I can also see the way the work of various historians, archaeologists and curators has been used. But I saw other visitors poring over the guns and exclaiming over the duels fought in Flagstaff Hill in the 1840s; parents earnestly explaining the overhead cistern and pull chain system of the toilets of Victorian Melbourne to their slightly disbelieving children. Visitors are offered an explanation of how such an extraordinary, yet familiar, thing as this city came into being, what shaped it, what it means to its citizens. For those wanting to pursue Melbourne's story further there is a lavish book, with a bibliography, to accompany a lively exhibition. The exhibition can also be visited online.[2]

The curators of The Melbourne Story have clearly wrestled with the deeper underlying questions facing all urban researchers: what is a city? How can such a diverse, ever-changing entity be portrayed, and explained in a finite space? One response evident in the exhibition is this: ordinary people are the city: the city is their stories. So The Melbourne Story is not so much about 'icons' but ordinary lives. It seems to have deliberately eschewed the easy path and the usual suspects, the famous and the clichéd: you will not find Chloe, the MCG, the 1956 Olympics, Menzies, Dame Edna, Leunig, or the Grand Prix. But you will find the big story in the shape of the Melbourne map, set at the heart of the exhibition. This is a quite extraordinary layered and multileveled lightbox, flickering and rippling with images, which summarises the city's physical expansion over time. Meanwhile, scattered throughout are the smaller, more intimate stories and images: sections of Melbourne's biggest family photograph album, to which Melburnians have contributed their favourite images. (As the exhibition explains, photography and Melbourne were born together.) A final film (or visitors could watch it at the beginning) opens with grunge rocker and actor Nick Cave talking about the city of his birth, followed by the reflections of other Melburnians, great, good and ordinary, accompanied by beautiful, fast-moving, triple-screened images. It does convey the essence and spirit of the place.

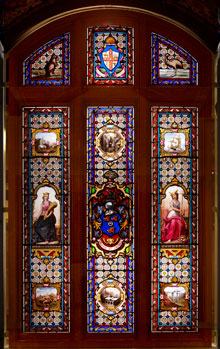

The curators of The Melbourne Story had the luxury of much of an entire floor with which to work — unlike, for example, the Museum of Sydney, where the galleries are relatively long and narrow, and broken up into separate spaces. The chronologically arranged sections are set in an arc, and they work well. Like the opening lines of a book that instantly make you want to keep reading, the view from the entrance is inviting: low-lit, kaleidoscopic, jewel-like. The exhibition is fairly clearly signposted by decades and historical phases, although the large chestnut horse in a glass case on your left draws you over irresistibly, before all else ('Look! His ears did twitch!'). No matter. Not far from Phar Lap's crystal coffin, we come upon the beginnings of Melbourne.

Museum Victoria

Melbourne's early history tends to be seen as a kind of 'prehistory', the time before gold changed everything, in the same way that Sydney before the arrival of Governor Macquarie is considered primitive and insignificant, simply marking time, awaiting the great man. Of course both were in fact lively, energetic and economically dynamic places in these early years. And although Melbourne is so often depicted as planned and orderly, as opposed to Sydney's convictism and disorder, I was struck and fascinated by their similarities — the same raffish, boisterous pre-industrial culture, the same duelling to satisfy manly honour, the same unmade tracks. This should not be surprising: after all they were founded by the same sorts of people. Melbourne's grid made no difference to the early social fabric, and was for many years more imaginary than real.

Early Melbourne is well represented by some wonderful foundational artefacts — the first printing press, belonging to John Batman's rival founder, John Pascoe Faulkner, and his handwritten first edition of the Melbourne Advertiser. Captions are appropriately frank: 'Hotels and beer played an important role in the council's beginning'. A photograph of surveyor Robert Hoddle shows him looking rather uncertain, and a copy of his celebrated plan of March 1837 reveals the grid tilted to run along the Yarra. The tension between these early Melburnians and the authorities in Sydney, who first declared them trespassers and then attempted to control them with grid, courthouse and lockup, is clear. It doesn't quite gel with some of the rather more staid settler material culture displayed nearby, though I suppose these are the sorts of items likely to survive and make their way into museum collections. The Scottish regalia and kilt belonging to Dugald McPherson is fabulous, but how common would such finery have been among the settlers of Port Phillip? What would have been the material culture of the convicts who fetched up here, who, we are told, made up half the male population by 1850? What did newcomers learn from the local environment and people?

The discovery of gold in 1851 is the overarching theme of the following section. The historical role of gold is almost biblical, separating the old Melbourne from the new. Evidently Melburnians were acutely aware of this right from the start. A marvellous three-dimensional model of the gold diggings at Daisy Hill, made in the late 1850s by Frederick McCoy, the director of the museum, testifies to this early history-mindedness, and the impulse to record and commemorate. It is also a neat way to introduce the museum itself into the exhibition. But the gold rushes are not presented in a simplistic way, as the straightforward bringer of wealth and people. Against the replica of a giant gold nugget (a clutch of small boys were giggling over it: 'a chicken nugget', one exclaims in glee), there is also the 'edgier history of gold' of historians David Goodman and Graeme Davison, telling of social upheaval and urban dysfunction, of the canvas town that sprang up on the outskirts of Melbourne.[4] Strangely, the painting The Mount Alexander Road, Flemington does not identify the long line of hopeful diggers as Chinese.

Museum Victoria

Museum Victoria

Museum Victoria

Museum Victoria

The presentation of the twentieth century, in sections titled 'Melbourne and the nation 1900–1920', 'Electric City 1920–1945', 'Suburban City 1945–1980', 'Changing City 1980–Present', tends to fuse Melbourne's particular urban story with the development of the nation, world events, and processes that occurred in cities worldwide. It also tries to cover an enormous amount of material and the effect is somewhat more staccato and scattered. A strength is the inclusion of popular culture (with the marvellous Luna Park ride), the lifeblood of any city, although it was surprising to see Australian Rules football relegated to one small corner — perhaps a deliberate playing down? Rock aficionados might quibble about some of the appropriations here. Yes, bands Skyhooks and GoSet were definitely Melbourne's, but AC/DC originated in Sydney, they just happened to be filmed performing on the back of a truck in Swanston Street. Compressing protests, festivals, celebration, commemoration and the Beatles under the rubric of 'public spaces and streets' does get people thinking about urban spaces, but tends to flatten out (and defuse) the meanings of these events.

It is a big exhibition and towards the end, when we explore Melbourne's twentieth-century suburbs, the curators have thoughtfully provided a replica 1960s lounge room, where you can flop on the lounge and watch bits of Homicide and The Graham Kennedy Show on the television. Nearby there's a reminder of a kitchen, with its neat, colourful canisters and handsome heavy Mixmaster. But on the wall is an unforgettable image of the external reality of so many post-war suburbs: muddy roads, quagmires and people trying to negotiate them. You can listen to the stories of four couples (including a charming gay male couple) who made new lives in these places. This is another high point in the exhibition, for it avoids the pitfalls of satire, clichés, kitsch and sentimentality which so often bedevil portrayals of suburbs, capturing instead something of the intimacy and emotional meanings of our most common urban landscapes.

It is fairly rare for Australian museums to present urban history at all, let alone both seriously and engagingly and with such obvious intellectual investment. This absence is puzzling, given the fact that Australia has always had among the highest rates of urbanisation in the world. Why aren't more museums presenting the stories of our cities? This exhibition offers all sorts of models for other Australian museums to explore the urban story, which is also a national story.

Grace Karskens is a senior lecturer in the School of History and Philosophy at the University of New South Wales.

1 Julie Marcus, 'Erotics and the Museum of Sydney', in A Dark Smudge Upon the Sand: Essays on Race, Guilt and the National Consciousness, LhR Press, Sydney, 1999, pp. 37–50.

2The museum's exhibition website is at:

http://museumvictoria.com.au/melbournemuseum/whatson/current-exhibitions/melbournestory/virtual-exhibition/.

3 Richard Broome, Aboriginal Victorians: A History since 1800, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005, Chapter 2; Robert Kenny, 'Tricks or treats? A case for Kulin knowing in Batman's treaty', History Australia, vol. 5, no. 2, 2008, 38.1 to 38.14.

4 See David Goodman, 'Making an edgier history of gold', and Graeme Davison, 'Gold-rush Melbourne', in Iain McCalman, Alexander Cook & Andrew Reeves (eds), Gold: Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001, pp. 23–36, 52–66.

| Institution: | Melbourne Museum |

| Exhibition: | The Melbourne Story |

| Curatorial Team: | Deb Tout-Smith (lead curator) in consultation with 14 other curators |

| Exhibition space: | 1200 square metres |

|

Venue/dates: | Melbourne Museum, Melbourne, ongoing |

| Publication: | Melbourne: A City of Stories, Deb Tout-Smith et al., Museum Victoria, A$39.95 |