by Nina Berrell

This paper explores the important work carried out by the first Aboriginal Arts Board in raising the profile of Aboriginal arts overseas in the 1970s, through a series of art exhibitions. It examines the circumstances that activated its international program, the content of the exhibitions and the response overseas. It draws attention to the board's efforts to kindle an alternative audience for Aboriginal arts, during a decade when local response was relatively indifferent.

____________________________________________________

The late 1980s are generally seen as the time that marked the first stirrings of overseas interest in Australian Aboriginal art. Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, an exhibition mounted by the South Australian Museum and the Asia Society Galleries (New York), played a pivotal role in the way Aboriginal art was perceived outside Australia. The show opened in 1988 in New York to high acclaim and triggered the first wave in a ripple effect of international interest. In its wake came an exhibition at the 1990 Venice Biennale of work by Rover Thomas and Trevor Nickolls. These were the first Indigenous artists to be represented in the Australian Pavilion and their works constituted the nation's official contribution to the biennale. A few years later Aratjara: Art of the First Australians attracted record-breaking crowds during its tour of Europe. However, it is sometimes forgotten that this moment of heightened awareness followed a period of intense activity and promotional work carried out offshore during the 1970s.

The driving force behind this adventurous activity was the Aboriginal Arts Board (AAB) of the Australia Council. Established in 1973 as one of the council's seven grant boards, one of its roles was to allocate public money for the promotion of 'traditional' and contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander arts.[1] The first members of the AAB took the view that their role was to stimulate audiences in the broadest of contexts, engaging the international community as well as the wider Australian population. Luke Taylor, while curator at the National Museum of Australia in 1990, specifically acknowledged the AAB's contribution to the increasing international recognition of Aboriginal art:It must also be said that exhibitions [such as Dreamings] follow in the footsteps of years of promotional work by other organisations such as the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council. The Aboriginal Arts Board was responsible for numerous exhibitions that toured overseas, for publications, and for the purchase of works that were given as gifts to overseas institutions in an effort to develop interest.[2]During the 1970s, the work of the 15 members of the AAB — including its two chairmen, Dick Roughsey Goolbalathaldin (1973–75) and Wandjuk Djuakan Marika (1975–79), its non-Indigenous director Robert (Bob) Edwards (1974–80) and its project officers — increased the exposure of Aboriginal art internationally through a rigorous program of exhibitions that were mounted in approximately 40 countries.[3] These shows were instigated by the AAB after consultation and discussion with Indigenous representatives from around Australia.[4] In this paper, I want to explore the circumstances that led to this program, its content and objectives, and some of the responses from the public and media overseas. My aim is to outline the history of an important early chapter in the spectacular rise to international prominence of Aboriginal art.

The first organisation specifically established by the Australian Government to build a market for Aboriginal arts was Aboriginal Arts and Crafts Pty Ltd (AAC), which was formed in 1971. AAC was set up by the then Federal Office of Aboriginal Affairs following the release of two tourist industry reports, which outlined the contribution that Aboriginal arts could make to the national tourist industry.[5] In particular, the reports recommended moves to expand the production of Aboriginal arts and crafts and to improve the ways in which they were marketed.[6] The formation of AAC, with its aim of developing a market through the establishment of retail outlets in major cities, was seen in government circles as a step towards achieving several goals within the new political paradigm of Indigenous self-determination.[7] The expectation was that its operations would contribute to the economic development of geographically remote Aboriginal communities in particular, and generate an income for Indigenous 'artists and craftsmen'.[8] One of its other functions — which would in time be absorbed within the policies of the AAB — was to promote greater appreciation and respect for Aboriginal arts practice within the wider Australian population.[9]

The newly elected prime minister, Gough Whitlam, articulated his government's aspirations in May 1973, in his address to Aboriginal Arts in Australia, a national seminar on the status of Aboriginal art and culture:We know that most Aboriginal Australians are proud of their heritage, of their long history, and of the traditions and culture which have been handed down to them ... Aboriginal people want to preserve their identity ... within an Australian society which respects and honours that identity.[10]

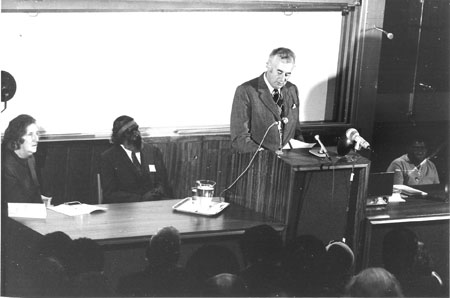

courtesy Anthony Wallis

(l–r) (back row) Raphael Apuatimi, Wandjuk Marika, Bill Reid, Bobby Barrdjaray Nganjmira, Eric Koo'oila, Terry Widders, Harold Blair, Chicka Dixon; (middle row) Violet (Vi) Stanton, Dick Roughsey, Leila Rankine, Kitty Dick, Brian Syron; (front row) David Mowaljari, Ken Colbung, Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri

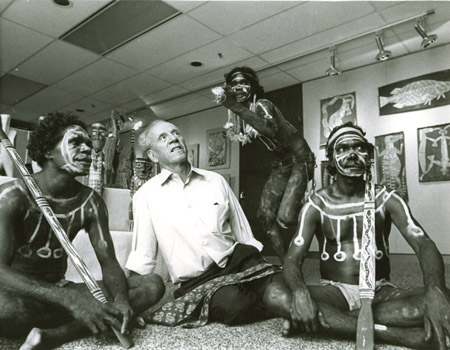

courtesy Robert Edwards

In her analysis of the AAB's activities, Christine Dyer points out that the AAB provided 'direct assistance to Aboriginal communities attempting to sustain (or revive) "traditional craft skills"'.[13] Tim Rowse also observes how early annual reports of the Australia Council stressed an emphasis on so-called 'traditional' arts (such as painting, woodcarving, weaving and dance) through words such as 'rebuilding', 'revival' and 're-establishment'.[14] It is clear, however, that from the outset funding was also extended to 'contemporary' arts in each major field, for example film making, dance, performance, ceramics, literature programs, recording projects and music festivals. Projects that reflected a 'living' and evolving art and culture were strongly encouraged and were compatible with the board's key concept of 'cultural maintenance'.[15]

Dyer also emphasises how the board's activities supported projects that were intended to promote broader public interest in the diversity and depth of Aboriginal art and culture. Art exhibitions were a means of doing this, but it proved difficult to find local art galleries to mount such exhibitions. Aboriginal 'artefacts' were still viewed by the galleries as tourist souvenirs or ethnographic objects rather than works of art. Even in 1981, an industry study commissioned by the Australia Council — the Pascoe report — divided Aboriginal arts into four categories, 'Ethnographic', 'Bi-cultural', 'Decorative' and 'Tourist', and evaluated the market appeal of each.[16] In the report, 'Decorative' and 'Bi-cultural artefacts' are described as having some aesthetic value, whereas 'Ethnographic artefacts' and 'Tourist artefacts' are classified, at the other end of the spectrum, as having 'low aesthetic value' and being 'crude and unappealing to Westerners'. Western Desert acrylic paintings were excluded from this analysis altogether and are simply noted elsewhere in the report as 'Transitional' works.[17] Published eight years after the AAB's inception, the Pascoe report reflects not only the patronising terms used for Indigenous arts at this time but also the aesthetic values that continued to prevail in the market.

For the AAB, changing prevailing attitudes to Indigenous arts appeared a much more difficult goal than the task of activating and rejuvenating artistic practice. Jennifer Isaacs, a project officer for the Aboriginal Arts Advisory Committee, and a consultant curator to the AAB throughout the 1970s, described the mood at the beginning of the decade:When the '70s began it really was a desolate scene indeed, or perhaps it simply seemed so from a white perspective ... Approaches by many of us involved at the time to galleries such as Rudi Komon, Kim Bonython, Terry Clune and others were not successful. Even the great Yirawala exhibition had not been accepted into State galleries ... and had to be shown in outsider venues such as universities.[18]Reviewing a 1978 exhibition of bark paintings from Oenpelli, displayed in a corridor court at the Australian Museum, art critic Nancy Borlase was critical of its positioning:

Whatever the arguments in favour of showing these works in this museum context, as paintings of high artistic quality they require the more detached atmosphere of an art gallery.The reluctance of the art cognoscenti to give Aboriginal arts a place within art galleries was, however, in complete contrast to what was taking place in Central and Northern Australia, where artistic production was strong, and distinct painting movements engaging different styles and media were well underway.

I am not alone in expressing these sentiments: the works are not there by choice. The Aboriginal Arts Board offered the exhibition to the Art Gallery of NSW which, in blunt terms, refused it. For whatever reason, the gallery was not interested enough.

Modest as it is in size, with 52 works, the exhibition would make an enormous impact in New York or Europe.[19]

Usually [under Australia Council policy] grants were given out, buying artists time to develop ideas. Our Indigenous representatives argued that this would not work [in the given context] ... 'Traditionally art has always been a part of the ritual cycle to ensure the continuation of food sources. We should rather buy the work, as this provides the means to obtain food.' And so this is exactly what the Board did. [21]According to anthropologist Fred Myers, who was based at Yayayi, near Papunya, in the mid-1970s, approximately 70 per cent of production by Western Desert artists was directly purchased by the AAB.[22] A significant number of works purchased by the board from throughout the Territory, which included bark paintings and carvings, weavings and fibre work from Arnhem Land and off its coast, including the Tiwi Islands, Croker Island, Elcho Island and Groote Eylandt, were destined for exhibitions overseas. Work was also acquired from Mornington Island in far north West Queensland and from Ernabella, Fregon and Amata in South Australia. The board's program was successful in several ways: it increased opportunities for artists to produce work for the art market, as well as for cultural and ceremonial reasons, and it generated a small income for those who took part. As the Australia Council's 1976–77 annual report recorded:

At a time when the market for Aboriginal works of art and artefacts has not entirely absorbed production, the Board has ensured a certain independence among Aboriginal artists and craftsmen by purchasing works for the Board's exhibition programme.[23]Despite the AAB's example, market confidence in the main was still a long way off. Edwards describes the typical response in an interview with Susan McCulloch:

No one else wanted to buy the art ... Papunya artists were in the first years incredibly prolific and we were building up quite a stockpile. Boards and canvases were stacked several feet deep around all the office walls and it started to worry the council and government auditors ... What on earth were we going to do [with them?] We tried to give [small collections] to galleries and museums [but few would accept them] ... They simply wouldn't [accept them] ... This was typical of much gallery reaction in the 1970s.[24]

Other than the Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, which purchased Papunya paintings intermittently throughout the 1970s, none of the state or national galleries acquired the first wave of Western Desert acrylic paintings as they were executed.[25] Paintings on bark using natural pigments and a restricted palette of earth colours had been included in public collections since the mid-1950s,[26] but there remained a reluctance to embrace the new work being produced; collecting institutions were generally cautious and acquisitions were few and far between.[27]

The commercial sector was also relatively static. Of the handful of 'specialist retailers' in this field, there were, nationwide, only two recorded as commercially viable by the end of the decade.[28] Although there was a small retail market to speak of, industry studies undertaken in 1973 and 1981 show that the majority of purchases were made by overseas visitors and tourists.[29] As the observations of both Myers and Edwards suggest, institutional purchasing within Australia continued to be dominated by the AAB. By the late 1970s, the board was firmly encouraging the inclusion of Indigenous art in public art collections. The first significant success in this project was in 1978 when the Art Gallery of South Australia accepted a gift of 20 acrylic paintings.[30]

However, this accumulation of paintings in community storerooms rather than on art gallery walls and in art collections affected the morale and output of artists. A report from a delegate to the national seminar in 1973 describes one artist's unease with the situation early on:

The key to the successful development of Aboriginal Arts and Crafts was given to me by one of the well-known bark painters from Arnhem Land. He said that the ritual or ceremonial leaders in his Country were unhappy with the treatment of their art. They saw their paintings dumped in craft rooms where they were not cared for or appreciated in the way they would have liked. As a result they no longer produce paintings of that quality or importance for the community craft organisation. If they were happy with the treatment and appreciation of their work the story might have been different, they would be completely behind the art and craft activities.[31]A few months later, at a meeting in Darwin, AAB member Wandjuk Marika warned that a large number of bark paintings were 'deteriorating in the store' at Yirrkala.[32] He pointed out that local artists were still working and many young people were anxious to participate. As paintings were now also being stacked against office walls in the Australia Council's North Sydney premises, 'good marketing' was considered essential from this point on. The situation must only have been exacerbated when, the following year, the board expanded its acquisition program to include paintings from the Western Desert. Already in Papunya, hundreds of works were being stored in a community building out of the public eye, owing mainly to inadequate storage facilities.[33]

Anthony Wallis, the AAB's first project officer, recalls bureaucratic pressure from government auditors, who queried the size and extent of the collections.[34] The meagre cash flow, generated by the AAB's purchases and the perseverance of a few small retailers and art centres such as Papunya Tula Artists, was sustaining the embryonic art movements — but only just. As the board's concerns were both industry and community focused, any solution would need to resolve the physical problems of oversupply as well as activate a new audience for the art. The strongest motive, however, was to maintain the momentum of the artistic enterprises.

The artists themselves, the driving force behind the practice, were interested in informing and educating the wider population about the unique artistic and cultural values inherent to the work. For many, the act of painting was most important for its capacity to project an intrinsic connection to Country. The board members understood the challenges confronting them and the constructive role that the arts could play towards achieving political goals and as a vehicle for communication of culture. What's more, the establishment of an arts board also increased opportunities for dialogue between artists around the country. This reality was sealed in Dick Roughsey's closing words at the national seminar, which pointed to the way ahead:Each of us, no matter how different our backgrounds, has this in common — that we are artists and that we are talking to each other through the arts ... at the end of this session the seminar will be over. But the spirit of the seminar will stay alive if the Aboriginal arts develop and become more widely known in Australia and other countries.[35]

(l–r) David Blanasi, HC (Nugget) Coombs (Australia Council Chairman), David Gulpilil and Dick Plummer

However, as Vivien Johnson points out, some members were adamant that important works should remain in Australia.[40] This concern was also raised a few months ahead of the opening of a touring exhibition to the United States in 1976 when, declining a request from the Department of Foreign Affairs, the AAB refused to donate any works from the developing 'National Collection'.[41] Thus, only after careful consideration, did the AAB decide to bypass an unsympathetic local market and set up an alternative program to exhibit internationally. It was a radical and visionary initiative. As raised at a meeting, in board member Chicka Dixon's assessment 'Australian people were generally ignorant and there were some advantages in gaining international acceptance to demonstrate Aboriginal art was world class'.[42]

Edwards recounts the circumstances surrounding the first major exhibition, Art of Aboriginal Australia, presented by Rothmans of Pall Mall, which toured 13 venues in Canada between 1974 and 1976:The Peter Stuyvesant Trust was very interested from the beginning and toured an exhibition of early Papunya paintings all around Australia ... this interest led to a request for a larger collection to feature at their festival in Stratford, Canada, and this show became the first major exhibition of Aboriginal art overseas ... 'But what happens when the show finishes?' I asked. [The AAB] believed it would adversely affect the local market if the collection came back to Australia. So we donated many of the works to the host venues after it had toured to a number of museums in Canada.[43]

Within a year of the successful Rothmans show, the chairman's report to the Australia Council listed six new exhibitions and, by 1976, the international component of the program was in full flight. Wandjuk Marika's recollection of his first year as chairman, recorded in his autobiography, maps some of the board's activities during a 12-month period. As one of the board's official dignitaries, he attended and contributed to exhibitions around the world, from New Mexico, USA, to Auckland, New Zealand, as well as project meetings in Lagos, regarding Nigeria's future cultural festival.[46]

In hindsight, Edwards suggests that the breadth and application of the program was perhaps 'one of the most subtle and brilliant marketing exercises' in the history of Australian art.[47] The strategy worked because many shows were tactfully inserted into other countries' cultural agendas. Where possible, exhibitions were pitched to coincide with national events and celebrations in host countries, within art festivals, or in conjunction with artist exchange programs. Participation in international art conferences and festivals, such as the World Craft Conference in Canada in 1974, the 2nd World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) in Nigeria in 1977 and the Pacific Arts Festival, held in New Zealand in 1976 and Papua New Guinea in 1980, reduced marketing costs and attracted attention from the public and the international media that might not have been achievable otherwise. These strategies helped offset the AAB's small budget, which represented less than 4 per cent of the Australia Council's funds in its first year, although revenue was regularly raised by other government departments such as the International Committee and the Craft Council, which collaborated with the AAB on several projects.[48] The Department of Foreign Affairs also facilitated communication with foreign embassies and often contributed towards shipping and insurance.

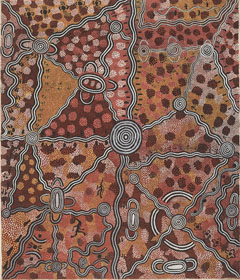

Life at Yuwa

by Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri

synthetic polymer paint on canvas

2009 x 1712 mm

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Life at Yuwa was included in an exhibition organised by the Aboriginal Arts Board in 1976, which toured to a number of New Zealand museums and coincided with the Pacific Arts Festival the same year. At its conclusion, a collection of canvases was presented to the New Zealand government and entered the collection of the National Museum.

The number of shows mounted overseas within a relatively short time was remarkable, as were their scale, size and attendance. For example, major touring exhibitions in Canada (1974–76) and the United States (1976–78) each included over 180 pieces. The director of the Public Museum, Grand Rapids, Michigan, reported that an estimated 29,000 people visited Art of the First Australians between September and November in 1978, which is a staggering record for an exhibition of relatively unknown artists and works.[49] Responses from Europe were equally encouraging. Arts and Crafts of the Australian Aboriginals drew the largest number of visitors to Madurodam at The Hague, the Netherlands, in 1976, and an exhibition in Warsaw, Poland, in 1979, also attracted strong attendance as well as television coverage.[50] It was estimated that over 10 million people had visited the exhibitions that were staged around the world between 1973 and 1979.[51] This achievement was little reported in the Australian press.

Internationally, it was different. Newspapers devoted considerable space to the shows, sometimes with full-page photographs, as did the journal Art International, which published a 20-page feature article in 1976.[52] Press publicity at The Hague exceeded all expectations, with nine newspapers publishing articles in relation to the Australian exhibition, varying from a few paragraphs to a quarter-page with photographs.[53] Critics generally praised the shows and responded enthusiastically to their content.

However, international response to the art varied. Some commentators approached the art primarily as ethnographic works, to be evaluated for their 'uniqueness' and 'authenticity' and function within 'traditional' Aboriginal culture. Indigenous art was viewed from this angle as static and unchanging and noted for its so-called 'mythological' and 'legendary' content, over and above its creativity and aesthetic innovation.[54] Others structured their discussion around modernist ideals of 'primitivism' and sought more general comparisons between so-called 'primitive art', and the use of bark, wood and natural pigments, and the artists' perceived links with 'nature'.

Some commentators, however, viewed the works within the context of contemporary art. This applied especially to the work of Western Desert artists. For example, acrylic paintings by Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri, exhibited in a museum renowned for its collection of 'folk art' in Albuquerque, New Mexico, were described in the New York Times as 'the most striking items ... They are complex pointillist abstractions that would look right at home in New York City's Museum of Modern Art'.[55] In another example from a newspaper in Vancouver, a collaborative work by Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri, Kappa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa, Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa and Eddie Edamintja Tjapangati received special mention:This abstract symbolism is combined with realism in the most striking work from the region ... Its symmetry is far more subtly achieved than in other instances and it integrates color, rhythm and density of motif in a composition which is extremely sophisticated.[56]

The latter remarks reflect the success of a deliberate strategy by the AAB to use Western Desert acrylics to demonstrate innovation within Aboriginal art's continuing tradition, and its high level of aesthetic beauty. Kate Khan, the AAB's project officer who, along with Edwards, purchased works by Papunya Tula artists for the exhibitions, points out that the selection criterion for inclusion in these exhibitions was aesthetic merit.[57] Ignoring the judgement of some Australian critics who viewed the depictions of traditional designs on canvas as 'hybrid', 'unauthentic' or even spurious,[58] the AAB ensured that a strong component of new work was included in major international touring shows. Dick Kimber, who first contacted Edwards about the new developments in Papunya in late 1971, described the board's director as the 'key outsider' who retained 'a strong belief in the beauty of these paintings'.[59] In other words, Edwards' first selection criterion in Papunya was aesthetic merit.

This belief informed the AAB's decision to illustrate the covers of exhibition catalogues, such as Art of the First Australians, with works by artists Shorty Lungkarta Tjungurrayi and Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri. The broad objective was to mount exhibitions that simultaneously expressed important artistic and cultural values through each artist's unique dialogue with the land. Although the exhibition venues — which included natural history museums, exhibition centres and foreign embassies, as well as art galleries — tended to contextualise the works within their own cultural frames, the AAB established protocols for presenting the works. As the board's exhibition catalogues show, commissioned paintings are attributed to their creator and, in later catalogues, are accompanied by more detailed biographies. The 1974 exhibition, Art of Aboriginal Australia, strengthens each artist's individuality through photographic portraits and, in so doing, attempts to undermine the notion of the anonymous artisan. This approach was clearly reinforced to host institutions: works gifted to five Canadian museums, upon the exhibition's conclusion, were 'presented on condition that they remain on permanent or semi-permanent exhibition, and display identification and credits to individual Aboriginal artists'.[60] It must be noted, however, that although paintings were attributed to their male painters, the creators of fibre works of art (such as string bags, dillybags and mats) invariably were not acknowledged within catalogues and displays prior to the 1980s. As Hetti Perkins, curator of the Aboriginal Women's Exhibition (Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1992), points out, what is considered the domain of women's art was, until recently, 'relegated to the anonymous sphere of "craft"'.[61]

Dyer's analysis of a catalogue for an exhibition of paintings from Gunbalanya (Oenpelli) — sent to major centres in Australia and Europe in the late 1970s — notes the inclusion of more detailed biographies, mentioning each artist's 'Subsection', 'Clan', and 'Country'.[62] She also points out another major departure from presentations in previous decades: in Oenpelli Paintings on Bark,[63] the chairman of the Gunbalanya Community Council, Joseph Burmada, and the AAB's second chairman, Wandjuk Marika, are heard directly through the publication's foreword and preface.[64] The words of his predecessor, Dick Roughsey, are printed in the AAB's first published exhibition catalogue of 1974. Dyer suggests the AAB's approach may be understood in part 'as a uniting of "Art" with "artefact"' — which is a fair assessment in light of the didactic nature of some of its earlier printed material and discussion of the 'utilitarian' function of artefacts and antiquities on display (such as carved boomerangs, spears, spear-throwers, shields and clubs), sometimes with documentary photographs, alongside exhibits of paintings. Nevertheless, the overriding observation, in contrast to previous decades, is one of transformation and change.

Most significantly, the AAB exhibitions lifted the paintings from sheltered storerooms and offices throughout Australia and displayed them in metropolitan galleries and museums overseas. Indigenous 'voices' were represented through the art on display, and also in person through the participation of artists and their representatives at exhibition openings and in artist exchanges. Where once Aboriginal people had been 'denied access to foreign cultural exchanges', now the board declared such exchanges to be their right.[65] Important artistic and political statements were now being clarified through the visual language of Australian Aboriginal art worldwide.

In this light, and as Roughsey had anticipated at the national seminar in 1973, the exhibitions were constructive forums for dialogue and exchange between artists, curators and audiences. Discussions with Indigenous artists in Albuquerque, New Mexico, prior to Australia's involvement in the American Bicentennial arts festival in 1976, show much was gained from these relationships. Board members agreed that the touring exhibition must first be sanctioned by the country's Native Americans, and in the case of the show in Albuquerque, Chicka Dixon met with the Navajo community a year ahead of its planned opening.[66] As reported in the New York Times, in an article titled 'Aboriginal art a hit in Albuquerque', 'Mr Dixon said he hoped the exhibition would mark the beginning of a mutually exciting cultural exchange between American Indians and Aboriginals'.[67]

Other opportunities for cultural interaction and exchange were provided by the Pacific Arts Festival that was held in Rotorua in 1976 and Port Moresby in 1980, and at FESTAC '77, which was mounted after a series of political setbacks in the host country, Nigeria.[68] Although discrete events in their own right, the exhibitions that travelled to these festivals provided rich backdrops to the groups of artists, performers, delegates and audiences in attendance. Within more culturally interactive forums, the artworks performed an important educational, as well as artistic, function.

Australia's contribution to FESTAC '77 indicates how rich and varied was the artistic talent upon which the projects could draw. Artists Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri and David Corby Tjapaltjarri travelled to Lagos in January 1977 for the opening of an exhibition of paintings, along with Indigenous representatives from each major artistic field, including the poet Kath Walker and playwright Jack Davis, dancers from Groote Eylandt and Aurukun, and members of the Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre group (established in 1976). 'The board is committed to ensuring that Aboriginal participation in the festival is of the highest standard', noted the chairman's report.[69] Nearly 60 countries were represented and contributed to the repertoire of art exhibitions, literary events, film screenings, and dance and theatre performances. Yet the Australian media provided little critical coverage of the program, focusing instead on tensions within the Australian delegation and any incidents that could be distorted to justify the African festival's perceived lack of sophistication.

The Bulletin, for example, reported 'soldiers waving guns and horsemen wielding whips'[70] at the opening ceremony, and how the 2000 pigeons due to be released 'were stolen and consumed by some of the Lagos citizens'.[71] Sensationalist and inaccurate stories were published over critical reviews of Australia's unique contribution, which gives something of an insight into the quality of attention of local newspapers — bar a few — to the AAB's international program.

Although the overseas exhibitions program of the AAB had been a conspicuous success, it did not survive long into the 1980s. 'Economic rationalism' took hold, and from this standpoint critics observed that the program had limited commercial benefits.[72] Exhibitions offshore were deemed too expensive and logistically demanding and were scaled down in number. There was a marked shift in approach, even towards AAC, with industry analysts emphasising national marketing all round. 'Offshore marketing has been given low priority', advised Pascoe in 1981; 'our view is that it should be taken off the agenda ... the real challenge is to develop a local market.'[73] That task was made much easier by the AAB's earlier successes in developing and touring overseas exhibitions.

The extent of success of the board's activities could well be measured by its perseverance and capacity to engage a foreign audience in the face of local indifference. From 1973 until the early 1980s, at a time when the wider Australian population showed limited interest in contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander arts, the AAB organised an impressive program of art exhibitions and placed works in international collections. This firmly positioned Aboriginal art on the international stage and prepared the ground for major exhibitions such as Dreamings in New York in 1988 and the subsequent surge of both national and international interest in these works.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

2 Luke Taylor, 'The role of collecting institutions', in Jon Altman & Luke Taylor (eds), Marketing Aboriginal Art in the 1990s, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1990, p. 33.

3 The members of the first board included Dick Roughsey (chairman), Raphael Apuatimi, Albert Barunga, Harold Blair, Ken Colbung, Kitty Dick, Charles (Chicka) Dixon, Ruby Hammond, Eric Koo'oila, Albert Lennon, Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, Wandjuk Marika, Mick Miller, Violet (Vi) Stanton and Terry Widders. Dick Roughsey OBE (about 1920–85) is recognised as an important Lardil artist and storyteller. The board's second chairman, Wandjuk Marika OBE (1927–87), is recognised as an important Rirratjingu artist and was a respected leader of Yirrkala. Both men were important cultural ambassadors for their people. Prior to his appointment, Bob Edwards AO had been closely involved in Aboriginal affairs as the curator of anthropology at the South Australian Museum (1965–73) and as deputy principal of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (1973–74). Edwards convened the Aboriginal Arts in Australia national seminar in 1973 and was officially appointed director by AAB members in 1974.

4 In 1973 board members agreed to deal directly 'with communities instead of through the central administration' (Australian Council for the Arts Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1973–1975, 3rd meeting, 11–13 August 1973).

5 Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company, Australia's Travel and Tourist Industry, Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company and Stanton Robbins and Co. Inc., Sydney, 1965; Harris, Kerr, Forster & Company, Tourism Plan for Central Australia, Honolulu, 1969. For further discussion see Altman, 'Marketing Aboriginal art', in Kleinert & Neale, p. 461; also, Nicolas Peterson, 'Aboriginal Arts and Crafts Pty Ltd: A brief history', in P Loveday & P Cooke (eds), Aboriginal Arts and Crafts and the Market, North Australia Research Unit, Australian National University, Darwin, 1983, pp. 60–5.

6 For further discussion, see Peterson, p. 60.

7 Self-determination was introduced as policy by the new Labor government in 1972. This era of political change can be traced back to the referendum of 1967, when an affirmative vote brought about changes to the constitution which had previously excluded Aboriginal people from the national census. Legislative changes made in August 1967 opened the way for changes in Indigenous welfare and for the advancement of human rights.

8 Peterson, pp. 60–1.

9 These were among AAC's objectives in 1975. It also aimed to 'foster the production of arts and crafts as a means of creating employment opportunities'. See Peterson, p. 61.

10 Transcript of speech by the Prime Minister EG Whitlam at the opening of a 'National Seminar on Aboriginal Arts', Australian National University, 21 May 1973, in Aboriginal Arts in Australia, Australian Council for the Arts, Aboriginal Arts Board, Canberra, 1973.

11 The Australian Council for the Arts was formed in 1968 under the chairmanship of Dr HC (Nugget) Coombs. It was renamed the Australia Council in 1973 and given statutory authority by the Australia Council Act in 1975.

12 Michael Dodson, 'Assimilation versus self-determination: No contest', North Australia Research Unit, Darwin, 1996.

13 Christine Adrian Dyer, 'A context: Kunwinjku art from Injalak 1991–1992, the John Kluge commission', in Christine Adrian Dyer (ed.), Kunwinjku Art from Injalak, Museum Art International, North Adelaide, 1994, p. 23.

14 Rowse, pp. 516–17.

15 For further discussion regarding the AAB's approach, see Fred Myers, Painting Culture: The Making of an Aboriginal High Art, Duke University Press, Durham, 2002, pp. 138–43.

16 Timothy Pascoe, 'Improving focus and efficiency in the marketing of Aboriginal artefacts', unpublished report to the Australia Council and Aboriginal Arts and Crafts Pty Ltd, 1981, pp. 21–2.

17 ibid., p. 20.

18 Jennifer Isaacs, 'The public face of Aboriginal art in the 70s and the 80s', Art Monthly Australia, vol. 56, 1992, p. 23. Yirawala was considered one of the greatest bark painters of his time. For example, in 1976 the National Gallery of Australia accepted a collection of his bark paintings from a private collector.

19 Nancy Borlase, 'Magical presence', Sydney Morning Herald, 9 December 1978, p. 16.

20 Jon Altman, 'Brokering Aboriginal art: A critical perspective on marketing, institutions, and the state', ed. by Ruth Rentschler, Deakin University, Geelong, 2005, p. 4.

21 Bob Edwards, letter to the author, 6 September 2007. Edwards discusses the AAB's acquisition system with Susan McCulloch, in Contemporary Aboriginal Art: A Guide to the Rebirth of an Ancient Culture, Allen & Unwin, Australia, 1999, pp. 32–3.

22 Myers, p. 136.

23 Australia Council, Annual Report 1976/77, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1978, p. 25.

24 McCulloch, p. 33. The bracketed insertions are my inferences.

25 For further discussion, see John Kean, 'Papunya place and time', in Vivien Johnson (ed.), Papunya Painting: Out of the Desert, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2007, p. 15, and Johnson, 'When Papunya Paintings became art', p. 31.

27 New accessions were often the result of the work and commitment of individuals and their supporters; for example, Frank Norton, the director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia (1958–75), commissioned and purchased artworks from the Kimberley and Arnhem Land during several field trips. Following Norton's retirement in 1975, the gallery's collection of Aboriginal art did not grow until the mid-1980s, as discussed in the essay 'Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth' (Brenda Croft & Michael O'Ferrall, in Susan Cochrane (ed.), Aboriginal Art Collections: Highlights from Australia's Public Museums and Galleries, Craftsman House, Sydney, 2001, p. 89). Similarly, during Tony Tuckson's employment as assistant and then deputy director of the Art Gallery New South Wales (1950–73), works from Arnhem Land, including the communities of Yirrkala, Milingimbi and Melville Island were incorporated into the gallery's collection from the 1950s, as discussed in Hetti Perkins' essay 'Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney' (Cochrane, pp. 43–4).

28 Pascoe, p. 10.

29 The Pascoe report (p. 42) found that AAC's customers were similar to those of independent retailers, and discovered that there had been little change in the market demographic since 1973 (the year in which an industry report prepared by Machmud Mackay, 'Marketing and Aboriginal arts and crafts', was presented to the Aboriginal Arts in Australia national seminar), with 60 to 75 per cent of purchases made by overseas tourists in both cases. According to Helen Hansen of Hogarth Galleries — one of the first commercial art galleries in Australia to exhibit Aboriginal art — the majority of the gallery's business in the late 1970s (then named the 'Gallery of Dreams') was generated by overseas tourists, particularly by buyers from the United States (Letter to the author, 9 October 2008).

30 For further discussion regarding the donation, see Jane Hylton, 'Art Gallery of South Australia' (Cochrane, p. 103).

31 Mackay.

32 Australian Council for the Arts Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1973–1975, 3rd meeting, 11–13 August 1973. Anthony Wallis recalls that the 'store' referred to was in fact the community's supermarket store. Adequate storage facilities at this time were virtually nonexistent (Letter to the author, 27 June 2008). Wallis was employed as an AAB project officer (1973–78).

33 See RG (Dick) Kimber, 'Papunya Tula art: Some recollections, August 1971 – October 1972', in Janet Maughan & Jenny Zimmer (eds), Dot and Circle: A Retrospective Survey of the Aboriginal Acrylic Paintings of Central Australia, Communication Services Unit, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne, 1986, pp. 43–5.

34 Wallis.

35 Transcript of speech by Dick Roughsey presented to the national seminar on Aboriginal Arts, Aboriginal Arts in Australia, 1973.

36 For example, in response to a proposed budget increase towards Australia's participation in the Nigerian arts festival FESTAC, meeting minutes record members debating whether overseas projects should be funded to the detriment of national programs (Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 5th meeting, 16–17 March 1976). Vivien Johnson draws attention to discussions of this nature (Johnson, p. 33).

37 Edwards, letter, 6 September 2007. This policy was apparently still active in late 1979: 'members agreed that the worldwide display of Aboriginal art on a permanent basis is the best means of promoting the arts of Aboriginal Australia' (AAB Minutes, 17th meeting, 13–14 November 1979).

38 Australian Council for the Arts Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1973–1975, 5th meeting, 3–5 March 1974.

39 ibid.

40 Johnson, p. 33. For further discussion regarding the AAB's commissioning program at Papunya in the mid to late 1970s, see Johnson, pp. 30–5.

41 Board members declared that much of the material in the National Collection was either sacred or an important part of national heritage and should remain in Australia (Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 5th meeting, 16–17 March 1976). This prerogative was recognised some years later in the Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986.

42 This is a record of Dixon's comment as it appears in the AAB meeting minutes, but is not necessarily a direct quote. Australian Council for the Arts Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1973–1975, 9th meeting, 5–7 October 1974.

43 Bob Edwards, letter to the author, 10 May 2002.

44 Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 17th meeting, 13–14 November 1979.

45 For example carved stone knives from Central Australia, held by Conzinc RioTinto of Australia.

46 Wandjuk Marika, Wandjuk Marika: Life Story, as told to Jennifer Isaacs, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1995, p. 121.

47 McCulloch, p. 33.

48 AAB budget figures recorded in Australian Council for the Arts, First Annual Report: January–December 1973, Canberra, 1974.

49 Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 15th meeting, 21–23 March 1979.

50 Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 7th meeting, 5–8 November 1976, and, Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 15th meeting, 21–23 March 1979.

52 Art International, vol. 20, nos 1–2, January–February, 1976, pp. 4–24.

53 Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 7th meeting, 5–8 November 1976.

54 For example: 'Canada will have permanent unique Aborigine art', Richmond Review, Friday 29 November 1974; Kay Kritzwiser, 'A very real glimpse of Aboriginal life at Stratford', Globe and Mail, Wednesday 5 June 1974.

55 G Lichtenstein, 'Aboriginal art a hit in Albuquerque', New York Times, 1 September 1976, p. 42.

56 J Lowndes, 'Spirit escape of eternal Dreaming', Sun, Vancouver, December 1974.

57 Kate Khan, letter to the author, 16 June 2008. Khan and Edwards made alternate trips to Papunya and surrounding areas, often accompanied by Daphne Williams of Papunya Tula Artists (from mid-1974). Khan was employed as AAB senior project officer (1974–78).

58 Bernice Murphy, curator of Perspecta 1981, suggests that acrylic paintings from Papunya were regarded as hybrid 'because of their expression in non-traditional materials', as cited by Hetti Perkins in 'From Genesis to genius', in Ian Chance (ed.), Kaltja Now, Indigenous Arts Australia, Wakefield Press & the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute — Tandanya, South Australia, 2001, p. 78.

59 RG Kimber, 'Recollections of Papunya Tula 1971–1980', in Hetti Perkins & Hannah Fink (eds), Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000, p. 206. Kimber notes his early correspondence with Edwards in 'Papunya Tula art: Some recollections, August 1971–October 1972', in Maughan & Zimmer, p. 44.

60 As reported by AAB director. Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 7th meeting, 5–8 November 1976.

61 Hetti Perkins, Aboriginal Women's Exhibition, Exhibition Catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1991, p. 7; Judith Ryan, senior curator of Indigenous art at the National Gallery of Victoria, argues that the absence of recognised women artists, prior to the 1980s, was also due to the Australian community's general belief, 'that Aboriginal art and religion were the preserve of men'. The 'implied presence' of Aboriginal women artists, 'as the nameless creators of many fibre objects, bears testimony to earlier methods of collecting and recording the artefacts of colonized Indigenous peoples, not yet dignified with either a name or a voice'. As quoted in her essay, 'Digging sticks and coolamons: Aboriginal women's art', Peintres Aborigènes d'Australie: le Rêve de la Fourmi à Miel, Parc de la Villette, Paris, 1997. For further discussion on this subject, and on textile arts in particular, see 'Prelude to canvas: Batik cadenzas wax lyrical', in Judith Ryan (ed.), Across the Desert: Aboriginal Batik from Central Australia, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2008, pp. 15–23.

62 Dyer, p. 24.

63 Oenpelli Paintings on Bark (1977) was presented by the Australian Gallery Directors' Council for the AAB. As Dyer points out, the AAB's collection of paintings from Gunbalanya was built upon a collection purchased from the Church Missionary Society in 1974. Additional bark paintings were then commissioned by the AAB to complement this initial acquisition, which together formed the exhibition.

64 ibid.

65 As stated in the meeting minutes, artist representation at international events was to specifically ensure the participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 'previously denied access to foreign cultural exchanges' (Australia Council Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1975–1979, 5th meeting, 16–17 March 1976).

66 The issue was raised in the project's early planning stages, and it was agreed that the proposal would not be adopted until consultations with the Indigenous peoples of the United States had been carried out (Australian Council for the Arts Aboriginal Arts Board, Minutes 1973–1975, 7th meeting, 22–24 June 1974).

67 G Lichtenstein.

68 This particular project was not at the outset initiated by the AAB; it was established by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, and then transferred to the Australia Council. Within the council FESTAC became an official component of their International Program with direct input from AAB members and staff. For example AAB members, Chicka Dixon and Wandjuk Marika, attended conferences in Lagos prior to the event and AAB project officer, Anthony Wallis, managed the arts tour to Nigeria in early 1977.

69 AAB, agenda item 4, 'Chairman's report to Council', 16–18 August 1975.

70 Brian Hoad, 'Black wasn't beautiful', Bulletin, 19 March 1977, pp. 42–4.

71 'Black brouhaha', Bulletin, 5 February 1977, p. 10.

72 For further discussion on this transition, see Myers, pp. 185–7.

73 Pascoe, pp. 66–7.