review by Stephen Martin

Two illuminating quotations appear in this wonderful book. The first is by Susan Sontag: 'to collect is to rescue things, valuable things from neglect, from oblivion, or simply from the ignoble destiny of being in someone else's collection rather than one's own'. French scientist Georges Cuvier places this in a scientific setting: 'science depends not only on its practioners but also on its organisers and entrepreneurs'.

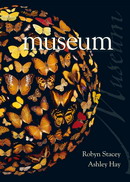

Collecting makes a world, a point beautifully made by Robyn Stacey's photograph on the cover of Museum: The Macleays, their Collection and the Search for Order, by Stacey and Ashley Hay. In this case it's a world of butterflies, created especially for the book. Several hundred of these creatures were pinned onto a black ball and photographed against a black background. The result is a round, intriguing, stellar view that highlights the individual item as an important part of the whole.

Stacey and Hay honour and feature the Macleay collection through photographs and carefully written text. Probably the oldest collection of scientific specimens in Australia, the Macleay began as the private collection of William Sharp Macleay, who brought it with him when he immigrated to New South Wales in 1826. The collection stayed in private hands, nurtured and expanded by Macleay family members, until it passed to the University of Sydney in 1887, as soon as a museum building had been constructed.

Like all similar collections, the vast majority of items are stored away from public view. Only two per cent of the Macleay Museum's collection is on display at any one time so the immediate visual context of 98 per cent of the collection is obscured, linked by number to records. Publicising this 'hidden' collection becomes a high priority in a time of cultural accountability.

And it is here that publications, including publications in digital format, assist many museums and similar institutions to disseminate more broadly information about their collections. In the digital age, museums, libraries and collecting institutions, given the resources, have an enormous opportunity to expand the reach of their collections. In the eyes of a serious researcher, a digital image (and a photograph for that matter) is no substitute for the real thing, but web works and books are a real and wonderful means of widening the impact of a particular collection.

Books like this serve several purposes. They expose the hidden collection and its meanings. Beautifully presented, as in this publication, they advertise and celebrate the richness of the collection. And in this form of publication they re-present the collection, adding new meanings to the chosen items.

This book is in a long line of creations about collections. Recent and diverse examples include Stephen Jay Gould's Finders, Keepers: Eight Collectors and the intriguing Tasmanian Art Gallery publication Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery with contributions by Matthew Baker and others, and photographs by Simon Cuthbert, published in 2007. Such books add value and creativity to the process of interpreting a collection. They present the collection in a specific light. The images are attractive, and include haunting, almost freakish photographs that invite questions — about the collection, the item and the public face of the museum.

Robyn Stacey began photographing the Macleay collection in 2001, and spent three years interpreting and photographing the collection items. An exhibition of her photographs ran at the museum from November to December 2007. In context or individually, the images are bright and attractive — one of the purposes of a book such as this. She enjoys re-interpreting the collection: 'It's always a thrill when my photos help people see a hidden collection or see an object from a totally different perspective '

Stacey, senior lecturer in the School of Communication Arts at the University of Western Sydney, has exhibited her photography in a number of solo and group exhibitions, and her work is widely represented in Australian collections. Ashley Hay is a well-known and widely respected author, whose enthusiasm for collections such as these (she previously worked with Robyn Stacey on Herbarium, a book of specimens from the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney) emerges in her clear and accessible style. Her commentary is backed by solid research, providing a history and deeper meaning to Stacey's intriguing images.

Visit the Macleay and, in the words of Ashley Hay:You'll see there one of the greatest historical collections in Australia — the first systemised inventory of natural history to be brought to these shores, the oldest and largest assembly of artefacts intended for teaching and instruction. Its there that you can see animals now extinct, animals beautiful or bizarre, and animals that stand as the definitive specimen of their species — those 'type' specimens studied and described when a species is first named, and the ones to which all others are subsequently compared. It's there that you'll see a collection through which one of the oldest stories of Australian science can be told.

This is a fine and carefully designed publication. Stacey's photographs are graphic and clearly presented. We see microscopic close ups (for example, a colourful shimmering examination of hummingbird feathers) and shots of cabinet drawers full of insects. Those who know the hypnotic appeal of an insect cabinet drawer will be well-served by this book.

The images are described, but at the end of the book — an arrangement intended to make the main text and images appear cleaner. While I can appreciate the glories of an image in itself, I always want to know more. The resulting need to flip back and forth can become tiresome. But this is a minor quibble. Pleasingly, the book has essay notes, a bibliography, an index and references for the text.

Stacey and Hay have a keen eye for the eccentric exhibit and item. For example two plaster prehistoric mammals seem almost to range out of the page in the 'Education' section. Originally purchased from Christopher Vetter, a manufacturer of 'Learning and Teaching materials and Young People's activities in Hamburg', the samples are two of 40. These wonderful animals, used no doubt initially as a teaching tool for the study of palaeontology, are now fine examples of the way we depicted such species in the late nineteenth century.

By beginning and maintaining a collection, the collector–organiser ensures that a particular creativity suffuses the collection. It may pass through several hands, be added to or have items withdrawn, but a collection remains as a testament to the inquiry and intellect of those who work with it. By making it more accessible and, as in this case, by reinterpreting items, others ensure the continued life of the collection. In doing so they recognise the efforts of all who have worked with the collection since its inception. Surely this is what Susan Sontag meant when she wrote so insightfully about collecting. It is certainly the impact of such a splendid book.

Stephen Martin is co-ordinating curator, Nelson Meers Foundation Heritage Collection, at the State Library of New South Wales.