It is a story I have used many times, particularly when speaking to groups of visitors to Australia. I was on a train in the United Kingdom and had got into conversation with a fellow traveller, as you do. He had asked what brought me to Britain; I had said that I was a historian, working in a couple of libraries. Wonderful, he had said, a historian; what is your field? Australian history, I had replied. Oh, he had asked, is there any? It was a story that I could not get out of my head as I made my first visit to the National Library to see the exhibition, National Treasures. This is our stuff, I kept saying to myself, our story, so let's not look down our noses at it.

And I remembered Edmund Campion's account of his visit to the National Library for Treasures from the World's Great Libraries in his thoughtful and meditative book Lines of My Life. Campion had come to Canberra from Sydney the day before especially for the exhibition, had woken very early and was at the Library and in the queue by 4.15am. He was admitted to the exhibition just before 7.00am and he thought that he might just spend all day there; he was enthralled. 'The actuality of everything in the exhibition space,' Campion wrote, 'was an important element; reproductions or photographs would merely have given you the information but would not have had the same impact on you. They would not have connected you to the real experience. By contrast, everyone who went to the Canberra exhibition came away with a heightened sense of the values we call civilised. The experience had transformed them.'

There is no great queue snaking its way among the pillars in Canberra for National Treasures. But why should there be, for this exhibition will travel to all states and territories, opening in Melbourne at the recently and grandly refurbished State Library in early March 2006 and to the other libraries in their turn. Still, on the days I have looked at National Treasures in Canberra, three days so far, the crowds have been steady and strong and, like Ed Campion for the earlier exhibition, deeply engaged.

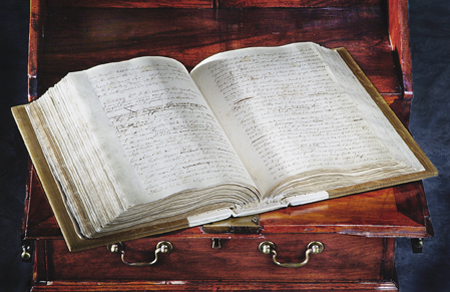

The exhibition displays over two hundred items, drawn from the collections of the National Library and all the state and territory libraries. The National Library has contributed the highest percentage of objects, about a quarter of the total, followed by the state libraries of South Australia, New South Wales and Victoria. The exact proportions from the various institutions will vary from one venue to the next, to take account of conservation and other requirements.

Of course the foundation documents are there. The Endeavour journal, Matthew Flinders' map, the first images of white settlement, evidence of the surprise in Australian fauna and flora. Yet the big items do not dominate this exhibition. It's whimsical, a friend said as she came out of National Treasures, and I think she had it precisely right. If these are the documents and pieces that tell our national story, and in large measure they are, then perhaps as a people we are whimsical and that is our story. Odd, fantastical, delicately fanciful, expressing gently humorous tolerance.

There is much that is odd in National Treasures. Fatso, the fat-arsed wombat, for example, one of the most loved elements of the wholly marvellous Sydney Olympics. Precisely right in National Treasures for that bit of our national story. We loved the Olympics, all of Australia embraced the Games, to be in Sydney in those days was very heaven, but we loved, too, Roy and HG with their nightly debunking on the Olympics broadcaster, Channel Seven. Silly Syd, Millie and Olly, a playtpus, an echidna and a kookaburra, were the official mascots of the Games ('to embody Sydney and the spirit of the Games') but they weren't in the same league as Fatso, who ends up in National Treasures; because Fatso had that element of self-mockery, self-deprecation, that is part of the Australian way.

Or the extraordinary silver and wood model of the Snowy Mountains scheme presented to the Governor-General, Sir William McKell, in thanks for his attendance in the mountains to inaugurate the scheme. This sets the mind wondering: why go to all the trouble? McKell, after all, was on official duty. What happens to other gifts to governors-general handed out to them for just doing their jobs? Are they all as elaborate as that today?

Then there is the evidence of whimsical library practice that National Treasures also discloses to the really discerning visitor. Look at the convict leg-irons in the 'Settlement, Land and Nature' section of the exhibition. Brutal, solid, fearsome. You wouldn't get too far locked into those things. Again the mind races: our inhumanity, the terror of our first beginnings; Port Arthur, a place of national shame. But look at the caption. Tasmanian c. 1840. State Library of Victoria. Pictures Collection. Pardon?

I'm reminded that libraries collect much more than works on paper. Nearly a fifth of the objects on display in Canberra are classified as (three-dimensional) objects. Manuscripts and printed material make up more than half the total, followed by paintings, prints and drawings, and photographs. Then come maps, sketchbooks and diaries, and oral history recordings.

In contrast to the convict jacket, the exhibition provides evidence of the civilisation and civility that came to Australia in the earliest days, and the skills that people brought with them. Was every military officer an accomplished artist? There is exquisite evidence to suggest that it might be so. Was every one of them an engaging diarist and observer? Again the evidence would lead you to think so. This is not drawn out for you in the text panels: rather, the beauty and significance of these works emerge in an understated way that is characteristic of the exhibition.

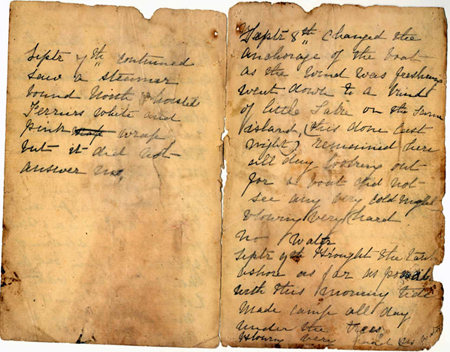

Some of the diaries make remarkable reading and it is the serendipitous nature of their presence here that sparks the imagination. I noticed that people really wanted to read what the diarists had set out for them, and made good use of the well-placed hand rails, just below the bottom of the glass of the exhibition cases: a design feature that other exhibitions would do well to emulate. For a game, go from one diary to the next, ignoring all that is not personally written and intimate to the writer. What variety of experience, narrative skill, and life experience you will discover. What sadness, too: Mary Watson's diary fragments detailing the last days of her life, and of her four-month-old son and Chinese servant, dying of thirst in a makeshift boat. Make sure, too, that you do not miss Shane Gould's diary, as touching an object in the exhibition as any.

Perhaps for me there was an element of predictability in some of the items on display. Am I the only Australian little moved by Ned Kelly's armour? Or Don Bradman's bat? (Though I was taken with his 1946-47 blazer: what a small man he must have been, or how tightly the blazer might have fitted.) I suppose the 'iconic' items draw the people in and the unexpected items arouse and astonish them.

But this is not really an exhibition for hardened old historians such as I. We have been lucky enough to have lived with this type of stuff all of our working lives. That it can still excite and stimulate us is tribute to the richness of the material on display. But the point of this exhibition is to open to those who would never normally make it to the manuscript reading room something of the joy and excitement to be found there. You could imagine someone deciding to become a historian of Australia, simply as a result of a visit to National Treasures. It could be, as Ed Campion found earlier, a transformative experience.

A cabinet of curiosities, that's what we need, one of the directors of the Australian War Memorial used to say. Let's stop directing people in the way we want to tell them the story; let them start discovering things for themselves. A cabinet of curiosities as our National Treasures? Randomly selected items to give the taste and flavour of the Australian story? I suppose those who worked so hard for this exhibition and met over so many long hours endlessly debating including this against that would give a wry smile at the idea that National Treasures has the feel of a cabinet of curiosities. But it does.

And it so suits the whimsicality of our story. Little bits and pieces, a surprise at every turn, telling us who we are and where we have come from. Material to study earnestly, to examine carefully, to laugh over with a friend, to reflect on privately; but none of it to pass over lightly. For this is an exhibition that tells us that we do indeed have a history; but our history is not like the history of other folk. And possibly only we can truly understand it. For, despite the best endeavours of those who do not understand us as a people (our politicians among them), we are not like all the peoples elsewhere. We are our own folk; telling us that is the achievement of this exhibition. National treasures, indeed.

Michael McKernan is a former academic and museum administrator. Now a writer and broadcaster, his most recent book is The Brumbies: the Super 12 Years.