Interpreting Home Hill house museum and the legacy of Joseph and Enid Lyons: Challenges and educational opportunities

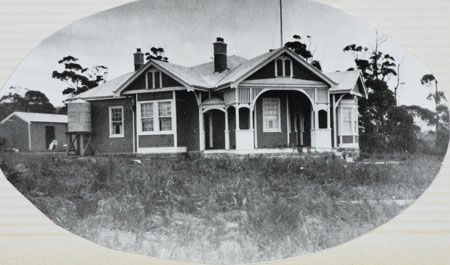

Homes can evoke powerful feelings of emotional attachment. Home Hill, the Tasmanian family home of Joseph Lyons, Australian prime minister from 1932 to 1939, and Dame Enid Lyons, the first woman to be elected to the Australian Federal House of Representatives (September 1943) and first female cabinet minister (1949), was sometimes described in lyrical terms by the political power couple. They chose the house design from builders’ plans and built the home in 1916 on the site of an orchard that Joseph purchased in Enid’s name and gave her as an engagement present in advance of their April 1915 marriage. To them it became a place of rest and renewal, for ‘two people never free during their lives together from the problems and anxieties of public office; never wholly free from the burden of immense responsibility’.[1] For Enid, the family residence came to possess quasi-mystical qualities – she depicted Home Hill as ‘Scarlet O’Hara’s “Tara” to me’ and, during a five-year hiatus period living away from the property when the family moved to Hobart, talked about it to her children ‘as though it were Paradise itself’.[2] Joseph echoed his wife, writing to her on 6 January 1932, the day on which he was sworn in as prime minister: ‘It has been a great day for me but I would be happier on the hill with you and all the children.’ In a poignant letter penned in early 1939, Joseph noted that he was ‘always longing for the time when, if God spares us, we can be together in our beautiful home, forgetting all the problems of politics’.[3] Sadly he was not spared, dying suddenly of a heart attack in April 1939 at the age of 59. Enid remained in the family home until her death in 1981.

Home Hill Museum Archive

Family circumstances are fundamental to better understanding the character of prime ministers – as private and public figures – and their domestic surroundings provide a unique opportunity to do this. Joseph Lyons’s marriage and home life were the bedrock of his existence.[4] Enid Lyons gave birth to 12 children between 1916 and 1933, one of whom (Garnet) died as a baby and, thus, Home Hill was for many years ‘filled throughout all the daylight hours with shouts of children either happily at play or fiercely fighting the unending battles of early development and the sound of little feet treading the linoleum-covered floors’.[5] Enid, at times affectionately referred to as ‘Australia’s greatest mother’ and perhaps ‘the best-known woman in the land during the ’30s and ’40s’, also painted an idyllic picture of family life at Home Hill, with children ‘playing hide-and-seek through its rambling rooms and in the tree-filled garden’.[6] Joseph skilfully exploited press photographs to convey the image of Enid as a devoted mother and his pride in his large and happy family. In her autobiography, Enid recalled that:

In the good climate and the open surroundings the children enjoyed almost perfect health. How I looked forward to the day’s end: to homework finished and baths taken, to the last ‘warm by the fire’, and to fresh young faces lifted in turn for a good night kiss, as one-by-one, strictly in rotation according to age, they went off to bed.

Home Hill Museum Archive

She recalled 1928 especially as ‘the loveliest year we ever knew of idyllic family life as we conceived it’.[7] In her later years, Enid Lyons lobbied local and state governments and the National Trust to purchase Home Hill, so that it could become a museum. Her decision to preserve Home Hill for the nation coincided with what historian Graeme Davison describes as a ‘surge of heritage activity promoted by the Hope and Pigott enquiries into the National Estate and into Museums and National Collections’.[8]

The Home Hill site is now owned by Devonport City Council and its contents by the National Trust (Tasmania). Home Hill has been conserved as Enid Lyons left it, and is open to the public. Enid admitted to friends that she had some trouble with members of her family, who did not want her to dispose of the house and its contents in the way that she did.[9] Peter Lyons, however, the youngest son, is on the record as saying that he felt his mother did the right thing ‘because if his parents’ belongings had been split up amongst the children they would have become scattered and lost to future generations of the Lyons’ family’.[10]

Home Hill Museum Archive

This article draws upon a project undertaken at Home Hill museum by second-year pre-service Bachelor of Education primary teachers at the University of Tasmania, as part of a unit introducing them to the aims and purposes of humanities and social sciences education, including history. Undertaken in partnership with the Tasmanian National Trust – and supported with funding from a Tasmanian Community Fund – the project aimed to create educational resources to shape and support school visits to Home Hill.

This paper has four main objectives: first, to place museum learning, and history education in museum contexts, within the framework of a wider research literature; secondly, to provide some brief introductory context to the significance of Joseph Lyons and Enid Lyons as public figures; thirdly, to explore some of the challenges of interpreting Home Hill to the general public and to primary school-aged children; and, finally, to outline the curricular and pedagogical choices that pre-service teachers made so as to engage primary school-aged during their visit to Home Hill. It outlines the ways in which they sought to bring history to life, explore ideas, and make connections between the past and the present. The paper is organised under these four broad themes.

The research literature context

International literature indicates that museums can fulfil an important educational role in helping young people derive meaning from artefacts and buildings and promote learning conversations.[11] Museums, in Tasmania as elsewhere, can be a powerful force for extending and enriching primary school students’ appreciation of key aspects of local and national history.[12] A number of Australian museum educators and researchers have drawn attention to the opportunity that the arrival of a national history curriculum provides for reinvigorating links with schools.[13] Artefacts and buildings can intrigue children, develop their powers of observation and explanation, help them establish meanings and make connections, stimulate their imagination, and foster a degree of empathy with the people – in this case the Lyons family – who inhabited a particular place. Museums are rich educational institutions that offer engaging opportunities for schools to stimulate children’s learning.[14]

Home Hill Museum Archive

The research literature also reveals, however, that teachers tend not to integrate museum experiences into classroom learning, set ill-defined educational objectives, and sometimes focus more upon the chase for information on site visits rather than higher order thinking and learning.[15] Moreover, there is recent Australian research evidence that suggests ‘teachers frequently find themselves out of their depth and feel inadequate, even frightened, when conducting excursions’.[16] The literature indicates that the relationship between museums and schools can be ‘problematic’.[17] Successful museum visits require effective preparation and what has been aptly described as an ‘entrance narrative’ to shape the on-site experience.[18] The visit itself also needs focus and planning to achieve an appropriate balance between pre-determined, structured activities and an element of open and opportunistic learning. And there needs to be a clear sense of the follow-up and end goal or outcomes of a museum visit – the experience should lead somewhere.[19] Rarely do these elements come together.

photograph by Peter Brett

An introduction to Joseph Lyons and Dame Enid Lyons

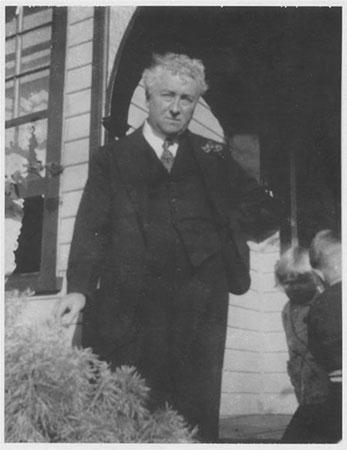

Both Joseph Lyons and Enid Lyons were substantial figures in Australian early 20th-century political history. Only recently has 21st-century heritage recognition and some sympathetic historical revisionism begun to revive interest in their achievements, which had fallen into relative obscurity.[20] So, for example, prominent sculptured busts of the couple were unveiled on the Devonport riverfront on Australia Day in 2000 and an interpretive panel honouring Enid was erected in May 2013, on a road named after her, adjacent to the National Library of Australia in Canberra. Joseph Lyons’s biographer describes him as having been ‘shoved off to some remote region of forgetfulness’ – in part a product, she argues, of dying in office before having written any memoirs but more, perhaps, because of his exceptional political allegiances.[21] Neither of the main political parties have included Joseph Lyons in their histories with any degree of enthusiasm. Lyons left the Australian Labor Party (ALP) in 1931 at the height of a financial crisis and is thus viewed by some on the left as having deserted the party. And, to those on the right, he has been regarded as someone who ‘simply held the fort during the 1930s, leading a government that contained men better than him’.[22] The United Australia Party (UAP), which Joseph Lyons founded in 1931, collapsed in the years after his death and, with the formation of the Liberal Party in the mid-1940s, Robert Menzies became the figure revered by conservatives in their narratives of party origins. Similarly, Enid, a conservative figure in spite of her commitment and contribution to women’s issues, was of little interest to post-1960s feminist academics. On many moral issues her views, guided by her adopted Catholic faith, were traditional: she disapproved of early sex education, homosexuality and promiscuity, opposed divorce and, in 1973, campaigned against abortion.[23]

The son of Irish Catholic migrants, Joseph Lyons started his career as a teacher who worked mainly in rural schools in Tasmania. In 1909, aged 32, he was elected as a Labor member to the state parliament and, as his Australian Dictionary of Biography entry notes, ‘between 1909 and 1922 Lyons described himself as a socialist, establishing a reputation as a firebrand’.[24] Lyons, however, set aside earlier anti-capitalist rhetoric to serve as a pragmatic, retrenching, consensual state premier in the years up to 1928. Following defeat at the 1928 state elections, Joseph entered federal politics during the Depression in November 1929 to be a key figure in James Scullin’s Labor government. As acting treasurer, however, Lyons refused to go against the advice of the Commonwealth Bank and resort to credit expansion and he objected to the decision of the ALP caucus to launch a £20 million public works program. He decided to break with the associations of a lifetime and leave the ALP and, in 1932, he became leader of the newly formed conservative UAP and prime minister of Australia.

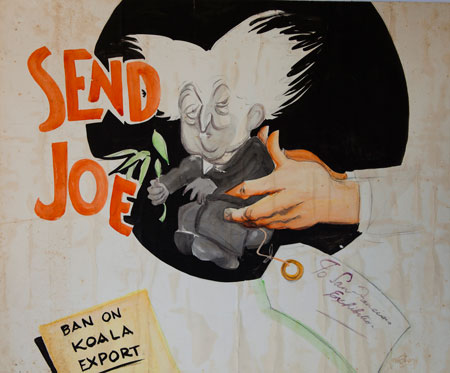

It was Joseph Lyons’s strength in the 1930s to see Australia through one of its darkest decades and to keep the government united. On the domestic front, he pursued unspectacular and prudent budgetary policies that served Australia well. On his death, the New York Times headlined its report, ‘The school teacher who beat the Depression’. Joseph Lyons has many significant achievements to his name and is now widely regarded as ranking among the more successful Australian prime ministers, as the first Australian national party leader to win three consecutive elections, in 1931, 1934 and 1937 respectively. He was often depicted by contemporary cartoonists as a koala, picking up perhaps on the swept back hair and the penetrating eyes – and, given the gentle and cuddly ubiquitous popularity of the koala, this was probably an astute cartoonists’ choice.

Home Hill Museum Archive

Joseph Lyons appealed to many ordinary Australians as a leader who spoke with simplicity and common sense. He obviously appreciated a favourable news cutting from an English county newspaper (that is kept in the Home Hill archive), which outlined ‘The triumph of “Honest Joe” Lyons’ in wiping out a financial deficit in 12 months:

Take a dreamy idealist whose qualities are academic rather than commercial, surround him with a large and flourishing family to whom he is devoted, endow him with good temper, humour, and a love of tranquillity; give him the personal appearance of an old-time actor, and the physique and skill of a first-rate athlete, and you have a picture of the Australian premier.[25]

Robert Menzies described Joseph Lyons in a 1966 ABC-TV documentary as a first-class parliamentarian, calm, good-humoured, shrewd, a brave man, a strong man and extremely adroit. Lyons’ leadership of the United Australia Party held together an eclectic group of independent, ex-labour and ex-conservative MPs.[26] He has been depicted as Australia’s first modern leader.[27] Taking office at a time of technological advances in communication, and in a dynamic partnership with his wife, he made forceful use of radio, film, air travel, telephone and cable in a way that echoes politicians’ engagement with new forms of communication today.

In foreign affairs, Joseph Lyons established positive relationships with such diverse individuals as Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain, Pope Pius XI and Benito Mussolini. In 1935 Joseph and Enid travelled to London for George V’s golden jubilee and trade negotiations and, in July, he featured on the front page of Time magazine. His advice was sought by Baldwin in handling Edward VIII’s abdication in 1936, and Joseph and Enid returned to London again in 1937 for the coronation of George VI. (There are some impressive artefacts from these visits on display at Home Hill).

David Bird sees Lyons’s involvement in the appeasement diplomacy of the 1930s in both Europe and East Asia as insufficiently recognised.[28] He twice visited Fascist Italy and met with Mussolini. In later years, Enid Lyons claimed that she had urged her husband to ring Neville Chamberlain in September 1938, at the time of the Czech crisis, in order to encourage him to utilise Mussolini in a last-minute mediation with Adolph Hitler. Lyons certainly believed himself to be due some of the credit for the subsequent Munich Pact. Yet appeasement and an active diplomatic policy were only one side of the coin; the other was rearmament. Lyons presided over the largest peacetime military expenditure per capita in Australian history and there were five major rearmament programs in the Lyons years – each with a wider range. Lyons’s prioritisation of expenditure on rearmament ‘both allowed Australia to be better prepared for the Second World War than would otherwise have been the case and also helped to kick-start the process of developing secondary industry in Australia’.[29]

Enid Lyons grew up in humble circumstances in north-west Tasmania where her father was an itinerant timber worker. As a 17-year-old trainee teacher, she married 35-year-old Joseph Lyons, who was then Tasmanian minister for education, and converted to Catholicism. She later remarked on her marriage: ‘Now, that was quite wonderful, wasn’t it? The junior teacher married the Minister’.[30] As well as bearing Joseph 12 children, she was his closest political ally and adviser.

It is the private and domestic woman who is most on show at Home Hill. Visitors wince on learning that Enid Lyons’s pelvis snapped when she had her first child and that the fracture was not picked up and confirmed until much later. When pregnant she made use of a homemade wheelchair, resting one knee on the chair seat. An excellent public speaker, with a particular interest in subjects relevant to women, she made a successful prime minister’s wife from 1931. In the couple’s travels abroad in 1935 and 1937, Enid was especially effective in supporting her husband, speaking at functions, and contributing columns to Australian and British newspapers.

After her husband’s death, Enid Lyons passed a few years at Home Hill, attending to the needs of her young family. Then, in 1943, she stood for election to the House of Representatives in the Tasmanian seat of Darwin, becoming the first woman elected to federal parliament. In her powerful maiden speech in September 1943 she discussed social security, the declining birth rate, the need for an extension of child endowment, housing, and the family:

I bear the name of one of whom it was said in this chamber that to him the problems of government were not problems of blue books, not problems of statistics, but problems of human values and human hearts and human feelings. That, it seems to me, is a concept of government that we might well cherish … I hope that I shall never forget that everything that takes place in this chamber goes out somewhere to strike a human heart, to influence the life of some fellow being.

Home Hill Museum archive

As the mother of 12 children, Enid Lyons had an unassailable claim to speak on family topics. Referring to population policy, for instance, she said her knowledge came not from reading with ‘her feet up on the mantelpiece’ but ‘from being knee deep in shawls and feeding bottles’.[31]

As a politician, Enid Lyons made a modest contribution to the politicisation of domesticity and espoused a popular form of what has been termed ‘maternalist politics’.[32] She worked to increase welfare payments to women and children, such as the extension of child endowment. She also campaigned for an end to discrimination against married women in the workforce, increases to the allowances paid to returned servicewomen and pensions for widows. A later Tasmanian politician, Michael Hodgman, who knew Enid Lyons well, recalled that, ‘She wasn’t a stuffy person. She had strong ideas on social justice. And she wasn’t your conservative at all. She was a reforming Liberal from good solid Labor stock. A good combination, actually’.[33] Nevertheless, the prominent display at Home Hill of a photograph of an 82-year-old Dame Enid Lyons in 1979 proudly meeting Margaret Thatcher, the Conservative British prime minister, in Canberra, would seem to indicate an element of self-identity as a Conservative by the end of her life.

Home Hill Museum archive

Following her retirement on health grounds in 1951, Enid Lyons continued to be active in public life. She wrote regular columns for the Australian Women’s Weekly. Between 1951 and 1962 she served as a commissioner of the Australian Broadcasting Commission. She was a longstanding member of the Liberal Party (1944–81), the Housewives Association and the Country Women’s League. She was the most highly decorated Australian woman of her generation, created a Dame in the Order of Australia in 1980 to complement her Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire, which was awarded in 1937. Television reporter George Negus signed off a 2003 documentary piece on Enid with, ‘It’s fair to say they just don’t make them like that anymore. Dame Enid Lyons – despite poor health, the first Australian woman to burst through the political glass ceiling into the boys’ club’.[34]

Overall, therefore, these are substantial and important lives for visitors and students to reflect upon and to make connections with.

Interpreting Home Hill

At the time that it was built, Home Hill lay two kilometres outside the port town of Devonport and was bordered by bushland. A 1923 aerial photograph taken from the town looking south indicates a sense of the property’s detachedness and isolation.

photograph by HJ King, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston

Now the site has been enveloped by suburbs and sits alongside a 1990s highway. Visitor numbers to the home are small – 2100 per year – 20 per cent of whom are members of school groups. Numbers also include visitors from the occasional passing cruise ship. Home Hill is exceptional among properties classified by the Tasmanian National Trust, which are mostly elegant 19th-century gentry homes or highly valued convict-related buildings. Enid Lyons acknowledged Home Hill’s unassuming character:

In all probability, if you are a lover of things antique, and devoted to ancient buildings, and most certainly if you pride yourself on a big thoroughly modern home, you would describe the house simply as old-fashioned; having a certain charm perhaps, an air of warmth and welcome, but inconvenient, high-ceilinged and prodigal of wasted space.[35]

It is a humble, weatherboard, one-storey family home, in unremarkable urban surroundings. Anna Henderson, biographer of both Joseph and Enid Lyons, argues that the modesty of the home speaks to Joseph Lyons affinity with ordinary Australians and is therefore ‘an appropriate legacy for the people’s prime minister’.[36]

There is rich social and political history to be explored here. Home Hill is a fully-fledged and authentic house museum, having had in its century of existence no full-time residents other than the Lyons family and the occasional caretaker, except for a brief period in the 1920s. Despite its understated setting in an apparent cultural backwater of regional Australia, Home Hill constitutes a key element of the cultural heritage of both Tasmania and the nation. Enid suggested that the perceptive visitor might ‘pause a moment to wonder just how great a part it played in the lives of those who created it …’:

… It has known scenes of tears and tumult, of triumph and jubilation, of disappointment, success and failure, scenes even of rebellion. Yet permeating all – an overflowing happiness.[37]

A telephone in the reconstructed office is a reminder that, when the first cables across Bass Strait established a telephone connection to the mainland in 1934, Home Hill was among the first Tasmanian households to avail itself of the new facility. Visitors can stand in Joseph Lyons’s office and listen to one of his New Year’s Day radio broadcasts, which he made from that room, to the nation as it emerged from economic depression in 1934. He also broadcast to all parts of Australia and to Papua New Guinea from Devonport in February 1939, briefing the Australian people on the uncertain and unstable international position in both Europe and East Asia.

The authenticity is impressive: the house is almost exactly as it was when Enid Lyons lived there and the grandchildren confirm it is just as they remember it from their childhoods (an exception is the decision made after Enid’s death by some of her daughters and National Trust curators to restore what had become a bedroom to its former status as Joseph’s office). Enid did her own interior decorating – she put up all of the wallpaper and upholstered the furniture. The guides delight in telling a story of how Enid painted one of the rooms with tendrils of green foliage in order to hide emerging cracks in the wall caused by nearby roadworks. And it was reported that Frances Lane, a secretary to Enid in her later life, ‘was very dogmatic about not changing anything in the house or garden – such as not covering the hall carpet even when it became threadbare’.[38] In terms of heritage values, every fibre of the carpet matters. The furnishings are as they were in 1976 and ‘Home Hill is basically as Dame Enid left it’.[39] Peter Lyons, the youngest of the Lyons children, recalled in a 2003 documentary, ‘Mum loved this house. And virtually, as each member of the family came along, they put another room on it. But she was dreadfully attached to it … It was her life. And, particularly after Dad died, it’s all she had’.[40]

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that what the visitor sees at Home Hill today is also a construct. There is evidence that Enid Lyons ‘was trying to create a vista effect, so that when you came in through the front door you could look right down through the rooms’.[41] The building would have had a far less formal feel as a family home in the 1930s. For example, the present-day dining room, full of memorabilia from royal visits to England and display cabinets of gifts and family crockery, was actually Joseph and Enid’s bedroom in the 1930s. And former doorways have been turned into display spaces. It has been argued that historic sites and museums should be considered by teachers as constructions or ‘readings’; teachers are advised to integrate them into the curriculum as sources in their own right, and thereby promote more sophisticated forms of historical understanding.[42] Perhaps part of the skill at house museum sites such as Home Hill is to be transparent about the complexity of the interpretational exercise and open in sharing the rationale behind why the building has been laid out in the way that it has.

The house was enlarged and renovated many times as the family grew, and reconfigured as children left home. Some of the current living area was once used for bedrooms. When the young couple first lived at Home Hill from 1915 to 1923 it lacked electricity, sewage, mains water and a telephone. Enid Lyons noted that ‘ever since we had been in Hobart I had longed for the house on the hill at Devonport’.[43] They returned in 1927 to a modernised house with electricity, telephone and mains water. One of their sons, Brendan Lyons, recalled from his childhood that ‘every time they came home from boarding school, they would have to work out how to get around the house, because changes were made constantly’.[44] In 1927, the four girls shared one fairly small bedroom. Because of the difference in ages of the children, however, together with periods when they were away at boarding school, rarely did all the children enjoy life at Home Hill at the same time.

Home Hill Museum archive

The current layout of the house has a sitting room beyond the front door flowing into a lounge room and then a dining room, which reflects the continual adding on of rooms, but also presents a unique open-plan living area that would have been ideal for such a large number of occupants and is also practical for managing visiting groups. The house had this organisation from around the 1950s.

There is a challenge in determining the picture of Enid Lyons that visitors and students take away from Home Hill. Enid used the media and her parliamentary speeches to craft her persona with care and, as we have seen, was noted for her use of homely and household metaphors to make political points. She referred to this practice as talking of politics ‘in terms of pots and pans and children’s shoes’.[45]

We can admire Enid Lyons’s determination and her articulate and literate defence of ‘Honest Joe’s’ legacy in her powerful memoir, So We Take Comfort, and in many interviews about their life together. But the projected image of idyllic and homely domesticity deserves an element of critical scrutiny. It has been noted that house museums tend to ignore the ‘nasty realities’ of women’s lives, including housework, food preparation, childbirth, contraception, childcare, disability, sickness, health, ageing and death among the realities and obligations that, while having shaped women’s lives, often have a veil of delicacy or voluntary forgetting thrown over them – ‘All such ideas have a major presence in the private-life realm of the house – yet make minimal showing in the interpretation of house museums, despite a raft of material objects’.[46] These were not themes that Enid would have chosen to underline, but her life and political interests – and the Home Hill setting – has the potential to speak meaningfully to most of them. The site curator reports that issues such as these do sometimes emerge spontaneously from audience questions, conversation or interest, but she and volunteers face the challenge of selectivity and pressures of time in supplementing the content of their core tour scripts. ‘Nasty realities’ only emerge serendipitously.

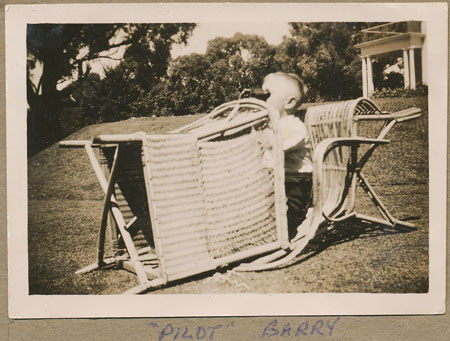

Enid Lyons’s constant political activity and childbearing took their toll. She often retired to hospital or took to bed from exhaustion and, in 1927–28, following the birth of her ninth child, Barry, who was born with dwarfism, she suffered from depression. The move back to north-west Tasmania was prompted by health concerns. She suffered a number of miscarriages until she had a hysterectomy in 1936.

Despite Enid Lyons’s public image as a domestic goddess and the undoubted pleasure which she took in her children, she had a relatively detached attitude to motherhood. She followed the influential contemporary advice of the New Zealand doctor Frederick Truby King not to handle babies too much (the avoidance of cuddling supposedly built character), although contrary to King’s advice she never breastfed her children. She received a lot of domestic help from other family members – her mother, her sisters, Joe’s sisters and especially his brother Tom and Tom’s wife Mavis. ‘Only the five youngest children lived at the Canberra Lodge. The others, aged from 9 to 16 years, were in boarding school and later at university. And when the older daughters left school they were called upon to take charge of the younger children, while their brothers continued their education. The youngest daughter Janice was sent to boarding school at age six’.[47] So, while Enid was a woman whose political addresses grew out of the rhetoric of the hearth, she regularly (and understandably given the size of her family and the extent of her public service commitments) delegated daily domestic activity to others. It would be interesting for interpretations at Home Hill to explore the compromises involved in balancing public and private lives. There are hints throughout Anne Henderson’s biography that the public life of the Lyons family on occasions took a toll on Enid’s relationship with her children. To acknowledge these maternal realities is not to diminish a life of exceptional achievement, but a broadening of the interpretive lens.

Professional memory workers, such as museum staff, must navigate a minefield of public demands and institutional conventions as they construct interpretations – usually on a limited budget. A 2012 report by Museums Australia refers to ‘the long history of lamentable neglect of the museums sector at the local community level across Australia’.[48] Even with a reputable governing organization like the National Trust, small regional museums like Home Hill exist on a hand-to-mouth financial basis, reliant upon volunteer staffing, and are subject to continual budgetary pressures and constrained resources.

Decisions regarding how to create interpretive narratives at historic house museums are complicated. Interpretative messages at sites like Home Hill are inevitably shaped by the ethos and expectations of the National Trust as an organization and its relationship with benefactors and members (and at Home Hill surviving family members remain as valued benefactors).The first goal of heritage interpretation is to express the significance of a site in clear ways that are also compelling enough to attract the interest of visitors; ‘“Why is this place so important that we want (or ought) to keep it?” should be the question, and it should be answered convincingly’.[49] As founders of the house museum genre, National Trust agendas have helped to shape the popular public vision of what should be shown in a historic house. House museums are constrained by the genre’s conventions of interpretation. The arrangement of furniture, decorations and domestic equipment is generally considered sufficient in itself to present the significance of the house, demonstrating why it is worth conserving and opening to the public.

Home Hill certainly benefits from owning – and therefore being able to display – a significant collection of Lyons memorabilia, including cartoons, photographs, costume and presentation pieces, books and antique furniture. Graeme Davison suggested that what many adult visitors value when they visit heritage sites such as Home Hill constitutes a mix of aesthetic reverence and preoccupation with the remains of the past with a kind of ‘psychic compensation’ and comfort in viewing aspects of the familiar past in a fast-changing, globalising world. For those disillusioned with modernity, such museums can ‘offer a pleasant respite from the visual monotony of [late] twentieth century architecture’.[50] Certainly, looking around the sitting room and bedrooms at Home Hill evokes a somewhat quieter, gentler and more harmonious age than our own.

Home Hill also falls loosely into the typology of the shrine of the ‘great man’, identified by Charlotte Smith as a commemorative space in which the hero’s (and heroine’s) relics and presence are intended to provide an intangible aura of meaning that speaks for itself.[51] It is difficult, however, to present complex stories via furnished settings alone. Moreover, ‘the expectation that viewing important, venerable things is the purpose of visiting house museums sets up a passive experience, which the static, frozen-moment nature of period rooms fulfils only too well’.[52] And on top of these factors, the presence of Joseph Lyons at Home Hill is, in any case, somewhat evanescent. Sam Malloy notes that ‘Despite the random reminders of Joe Lyons as a family man, the contemporary visitor to the house cannot help but feel completely overwhelmed by Enid Lyons’s presence’, and that, therefore, ‘the essence of Joe is mainly represented through isolated objects and stories told to visitors through guided tours’.[53] In short, the simple presentation of a furnished interior, however fascinating and rich in meaning the individual cultural artefacts might be, is not enough to carry big historical themes about the lives and experiences of Joseph Lyons and Enid Lyons.

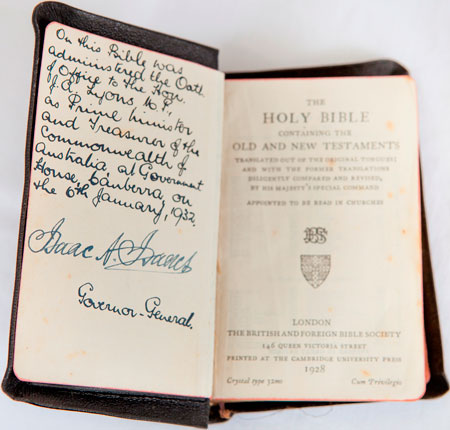

The Hope Committee of Enquiry into the National Estate of 1974 defined the national estate as ‘the things we keep’ and conserve from the ravages of decay or simply a quiet fading away into obscurity.[54] A balancing act is required, however, between ideas and things when creating interpretive plans for historic house museums.[55] There are certainly plenty of fascinating artefacts and objects to prompt visitor and student reflection at Home Hill. The house is full of political relics, including the Bible on which Joseph Lyons was sworn in as prime minister.

Home Hill Museum

The impressive 1930s clock that sits on the mantelpiece was presented to Joseph Lyons in 1936 following his opening of Holden’s new headquarters and assembly plant in Port Melbourne. It is a memento of the genesis of the local car industry in Australia (although the first all-Australian Holden car did not come off the production line until 1948).

Home Hill Museum archive

Items like these prompt ideas and deeper thinking; once intrigued by objects, visitors and children will hopefully think, observe, connect, question, empathise and imagine, and want to learn more.

Some analyses of historic house museums, however, have noted the danger of presenting a house and its contents as the ‘be-all and end-all’ of the interpretation:

The object’s greatest interpretive contribution is as a piece of the puzzle that, when assembled presents settings and suggests meanings. Objects, taken collectively, give context and structure to the realities of domestic living. House museums are likely to overlook this potential when a larger framework within which to place and sort fragments of information is absent.[56]

A museum will not leave visitors with a lasting message if it does not organize information into ideas that can be readily embedded into the interpretation. In educational contexts, children need to be able to see the ‘big picture’ story and context of their learning before they are able to derive meaning from places, buildings and their contents.[57]

A presentation plan for Home Hill was drafted in 2008 that acknowledged both a lack of space for group activities and school groups and ‘a lack of facilities for interpretation of Home Hill and the contribution of Joseph Lyons, Enid Lyons and their family to public life in Tasmania and Australia’. The report identified as an objective the use of ‘a dynamic range of interpretive information to highlight for residents and visitors the historical and cultural relevance of Home Hill’ and recognized the importance of ‘staying relevant to the market given the move away from attractions that offer a passive experience to those attractions that actively engage visitors’.[58] Until recently the only interpretation has been that offered orally – and with knowledgeable enthusiasm – by the site manager or volunteers on guided tours. A brochure of information about the house and Joseph and Enid Lyons is available for purchase, but there have been no on-site self-guided interpretative materials or display boards to offer visitors or students any idea of the lives and achievements of Home Hills’s former residents. Signage and display boards – apart from their expense – have been determined by the National Trust in the case of Home Hill to be intrusive and to dilute the authenticity of viewing the home. A new audiovisual site experience has recently been created.

A long-term answer to the lack of interpretive and contextualising material would be the construction of an adjacent purpose-built interpretation centre, comparable to the centre opened in 2010 at the home of another prime minister, Ben Chifley, in Bathurst, New South Wales. There, a neighbouring house was acquired to serve the purpose.[59] National Heritage recognition – perhaps across a triumvirate of prime ministerial homes (Lyons, Curtin and Chifley) – would assist with this ambition. The Home Hill site is of a size to accommodate a modestly sized interpretation centre, and there has already been significant investment in car-parking space and facilities. A shorter term solution would be to develop a more thematic and focused use of the L-shaped family living room, which currently displays a range of photographs of Joseph Lyons and his family. The space is available for public, educational and occasional commercial use, but it is not part of the main tour of the house. This would be consistent with claims to authenticity, as Enid Lyons intended the L-shaped room to be open to the public.

Pre-service teachers design learning at Home Hill

The outcomes that most primary teachers seek from a visit to Home Hill is to give their students the opportunity to learn in rich, contextual and focused ways about prescribed areas of the Australian History Curriculum (AHC). This curriculum assumes that ‘students’ interest and enjoyment of history can be enhanced through a variety of approaches, such as the use of artefacts, museums, historical sites and hands-on activities’.[60] The Year 1 AHC (for children aged five to six years old) has opportunities to explore past family life and one of the key inquiry questions is, ‘How can we show that the present is different from or similar to the past?’ The Year 2 curriculum has a specific focus on local history and the relationship between the past and the present. Key inquiry questions include: ‘What aspects of the past can you see today?’ ‘What do they tell us?’ and ‘What remains of the past are important to the local community?’ The Year 3 curriculum also explores local identity in the context of the theme of ‘Community and remembrance’. Children have the opportunity to investigate ‘the importance today of a [local] historical site of cultural or spiritual significance; for example, a community building, a landmark, [or] a war memorial’. The Year 4 to Year 6 curriculum follows Australian history from first contacts, through the process of settlement and colonisation in the 18th and 19th century to – in Year 6 – Australia’s 20th-century development as a nation. The pre-service teachers who worked on learning sequences at Home Hill saw opportunities to develop lessons for primary-aged students in years 1, 2, 3 and 6 in line with the curriculum imperatives.

The pre-service teachers asked a range of ‘key questions’ that offered effective thematic focus to the children’s work. Year 1 sequences explored what it would have been like to play and to celebrate in this house, drawing on some of the toys, games and photographs of children at play from the Home Hill collection: ‘What did the Lyons children play with?’ ‘How do you know?’ ‘Would you have like to have lived in the house when the Lyons children did?’ and ‘Why/why not?’ Year 2 sequences also contained a range of probing questions: ‘What is different between your house and the Lyons house?’ ‘How did the people who lived here use technology?’ and ‘With a focus on Joseph Lyons’s office, how has communication technology advanced since the early twentieth century?’ A Year 3 sequence asked, ‘Why might Home Hill be a special place now?’ and ‘What makes Joseph Lyons an important person in Australia’s 20th-century history?’ Year 6 questions included, ‘What do politicians do and what makes them successful?’ ‘What kind of a politician was Joseph Lyons?’ ‘What are the best ways of finding out about Joseph Lyons?’ ‘What significance did Dame Enid Lyons have on the development of the role of women in Australia?’ and ‘How have gender roles developed between the 1930s and now?’

Home Hill Museum archive

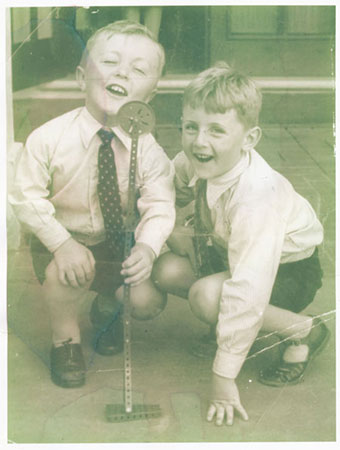

Several of the planned lessons encouraged children to ‘shift boundaries between the past and the present’[61] in engaging ways. For example, in a Year 1 sequence, one of the lessons encouraged the children to examine and talk about photographs from Home Hill and the prime ministerial Lodge in Canberra of the Lyons children at play with toys such as the Home Hill fire brigade, ‘Pilot Barry’, a meccano radio microphone, and a spinning top. As well as answering specific prompts about each image, the children considered the question, ‘How are these games similar to or different from the games you play now?’ After watching a clip on Scootle[62] that gave them an example of how an interview is conducted, the children were asked to interview a family member about a favourite toy from their past. The sequence also organised for the children to play traditional games, such as quoits, marbles, hopscotch and skipping on their visit to Home Hill, thereby making use of the property’s garden and grounds within an overall objective of exploring ‘differences and similarities between students’ daily lives and life during their parents’ and grandparents’ childhoods’ in relation to use of leisure time.[63]

A Year 3 sequence of lessons incorporated a similarly dynamic dialogue between past and present. Before their visit to Home Hill, children listened to and reflected on a 2014 New Year’s speech by Prime Minister Tony Abbott and were asked to compare it with a speech by Joseph Lyons, which they listened to in his office. They were asked to list five things that were different from the contemporary prime ministerial address and to reflect on the requirements of being an effective prime minister. The sequence had a communication theme and made use of copies of letters that Joseph Lyons and Enid Lyons had sent home to their children while travelling, including letterheads from Windsor Castle and the White House. For example:

Windsor Castle (9 April, 1935)

Dear Brendan

This is a card from Lancaster Tower in Windsor Castle, the palace of the King and Queen. We stayed there last night.

Love from Mum & Dad

This was followed by discussion of the 1930s postal service, the place of letter-writing then and now, and changes in forms of communication. The main assessment task for the children was to use a distinctively 21st-century piece of technology – an iPad – to create a presentation about one of the technological artefacts on display at Home Hill; for example, a typewriter, a 1930s phone, a 1950s phone, a pen and nib, or a 1930s gramophone/radio player.

Home Hill Museum

A Year 6 sequence, for example, incorporated a collaborative web search to stimulate exploration of Enid Lyons’s life, and roles as researcher, writer, or publisher were allocated to students. The sequence challenged the children to create a virtual museum exhibit focusing on Enid by selecting six artefacts, including at least two from Home Hill, detailing her story and exemplifying why she is a significant woman in Australian history. The children looked at example exhibits from the National Museum of Australia for ideas and inspiration. Another Year 6 sequence of lessons on Joseph Lyons set up a paired research task directing students to 10 different websites. Each pair was allocated two different websites to consult and to answer the question: ‘What do you see as Joseph Lyons’s four most important life achievements as a politician at state and federal levels?’ Students organized their four responses around an image of their choice. In a plenary review of their work the class explored a range of questions: ‘Why did groups make different choices?’, ‘What are the criteria for good research using the internet to find out about historical events and to draw historical conclusions?’, ‘Do the students think all of the sites are equally valuable?’, and ‘How do we decide upon what will be the most useful, comprehensive, and trustworthy sources of information?’.

The pre-service teachers also identified key elements of conceptual historical understanding that might be unlocked by a visit to Home Hill, with opportunities to foreground concepts such as uses of evidence, significance, and change over time. In terms of structuring thinking about artefacts, Year 6 questions included: ‘What do you learn from the images of Joseph Lyons that are on display in the office and in the L-shaped room?’ and, ‘What do artefacts at Home Hill tell us about Joseph Lyons and the British monarchy?’. In assessing significance, another Year 6 sequence included an ambitious comparative task whereby children worked collaboratively to research the life of one of six Australian prime ministers – Joseph Lyons, John Curtin, Ben Chifley, Robert Menzies, Bob Hawke, and John Howard – based on information on the National Archives of Australia website. The groups were required to argue a case as to who they thought was the most influential prime minister and they could choose how they presented their arguments to best effect and how they allocated roles. Students peer-assessed each others’ presentations against a rubric.

Home Hill staff were able to make some use of the lesson planning the pre-service teachers submitted and the real-life dimension to their planning undoubtedly enhanced their motivation: they agreed to their work being used by the museum and local teachers as additional learning resources to augment the museum’s existing support materials and, thus, they were engaged in more than an artificial academic exercise – children would get to road-test the learning activities that they designed.

Conclusion

Museums occupy an ambivalent place in the public imagination. Is their purpose primarily to commemorate, teach or entertain? To ask questions or to answer them? This article echoes the 1975 Pigott Report into museums and history in Australia, which articulated a dynamic and educative role for museums ‘stimulating legitimate doubt and thoughtful discussion’ and arousing curiosity.[64] Museum visit experiences are most beneficial – for both young people and the wider visiting public – when they engage people in a participatory process of interpretation and discovery.[65] At present it cannot be claimed that – despite the valiant endeavours of the people caring for them – Home Hill, or most traditional house museums, attain this benchmark. It has been suggested here that the future success and viability of Home Hill depends upon the ability of its owners, Devonport City Council and the Tasmanian National Trust, to abstract from the material reality of the house the broader social and political themes that can be found in the lives of Joseph and Enid Lyons, and to project a narrative that connects with and speaks to 21st-century interests and ideals. The best way of making a case for the importance and significance of a building is ‘by telling a rich, evocative, and complex story about it’.[66] At present the story is only implicit at Home Hill – which is frustrating when the central characters and the themes could illuminate so many questions about Australia’s relatively recent past.

A good central question to frame a visit to Home Hill might be, ‘How did visiting this place – and learning something about the Lyons family – make you feel?’ The three central pillars of place-based pedagogy, as part of an integrated approach to thinking about children’s learning, seem particularly apposite in the context of Home Hill. These pillars incorporate ‘storying’, or telling different accounts of a place and its inhabitants across time; offering embodied experiences (calling upon the five senses); and embracing places as spaces of ideas and contestation.[67] The pre-service teachers’ ideas drew upon this engaging form of pedagogy. At a site of memory such as Home Hill, forces of feelings must be part of any interpretation of the site. Museums can foster an emotional attachment to the past – which in turn triggers cognitive connections to ideas and higher order concepts – that cumulatively creates enjoyable and purposeful learning. Teachers have a crucial role to play in structuring learning to achieve this objective.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

Endnotes

1 Brendan Lyons (ed.), Home Hill: Some Reflections by Dame Enid Lyons, National Trust of Australia (Tasmania), Launceston, 2005, p. 1.

2 Enid Lyons, So We Take Comfort, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1965, p. 140.

3 A Henderson, Enid Lyons: Leading Lady to a Nation, Pluto Press Australia, North Melbourne, 2008, p. 174; A Henderson, Joseph Lyons: The People’s Prime Minister, New South Wales Press, Kensington, p. 424.

4 See K White, A Political Love Story: Joe and Enid Lyons, Penguin, Ringwood, Vic., 1987.

5 Brendan Lyons, Home Hill,p. 9.

6 National Archives of Australia, Joseph Lyons: Guide to Archives of Australia’s Prime Ministers, Canberra, 2005, p. 75; G Negus, ‘Dame Enid Lyons’, transcript from George Negus Tonight, ABC Radio, 22 Sep. 2003, www.abc.net.au/gnt/history/Transcripts/s951058.htm, viewed 12 February 2015; Brendan Lyons, Home Hill,p. 1.

7 Enid Lyons, So We Take Comfort, pp. 142–43.

8 G Davison, The Use and Abuse of Australian History,Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, NSW, 2000, p. 118.

9 Oral history evidence, Faye Gardam, Home Hill archive, 18 February 2010.

10 Oral history evidence, Peter Lyons (senior), Home Hill archive, 2009.

11 For example, E Hooper-Greenhill, ‘The power of museum pedagogy’, in H Genoways (ed.), Museum Philosophy for the Twenty-First Century, Altamira Press, Oxford, 2006, pp. 235–45; G Leinhardt, K Crowley & K Knutson (eds), Learning Conversations in Museums, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, 2002; C Van Boxtel, S Klein & E Snoep (eds), Heritage Education: Challenges in Dealing with the Past, Erfgoed Nederland, Amsterdam, 2011.

12 P Brett, ‘“The sacred spark of wonder”: Local museums, Australian curriculum history, and pre-service primary teacher education: A Tasmanian case study’, Australian Journal of Teacher Education, vol. 39, no. 6, 2014, 17–29.

13 For example, J Molloy, ‘Teaching and learning history in the twenty-first century: Museums and the national curriculum’, Agora, vol. 45, no. 2, 2010, 62–7; L Zarmati, ‘Why a national history curriculum needs a museum site study’, reCollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 4, no. 1, 2009, 1–12.

14 AS Marcus, JD Stoddard & W Woodward, Teaching History with Museums, Routledge, New York, 2012; L Suda & J Molloy, ‘Cultural institutions and SOSE: Learning the social in museums’, The Social Educator, vol. 26, no. 3, 2008, 26–32.

15 E Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance, Routledge, Oxford, 2007.

16 J Griffin, ‘The museum education mix: Students, teachers and museum educators’, in D Griffin & L Paroissien, Understanding Museums: Australian Museums and Museology, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2011, nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/JGriffin_2011.html, viewed 10 December 2012.

17 D Mathewson & P McKeon, ‘Disrupting notions of collaboration: The problematic engagement of museums and schools’, paper presented at the annual conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Brisbane, 1–5 December 2002, p. 1, www.aare.edu.au/02pap/mat02555.htm, viewed 10 December 2012.

18 Z Doering, & A Pekarik, ‘Questioning the entrance narrative’, Journal of Museum Education, vol. 21, no. 3, 1996, 20–23.

19 AM Noel & MA Colopy, ‘Making history field trips meaningful: Teachers and site educators’ perspectives on teaching materials’, Theory and Research in Social Education, vol. 34, 2006, 553–68, dx.doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2006.10473321.

20 Henderson, Joseph Lyons; D Bird, J.A. Lyons — The Tame Tasmanian Appeasement and Rearmament in Australia 1932–39,Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne, Vic., 2008; Henderson, Enid Lyons.

21 A Henderson, ‘Joseph Lyons – Australia’s Depression prime minister’, Papers on Parliament, no. 58, www.aph.gov.au/senate/~/~/link.aspx?_id=2B7DA45CC29D4108A58D155A4E4A7D02&_z=z, viewed 5 February 2015.

22 G Melleuish, ‘The national character in Joe Lyons’, Quadrant Online, 2012, quadrant.org.au/magazine/2012/01-02/the-national-character-in-joe-lyons/, viewed 6 February 2015.

23 A Henderson, ‘Faith and politics – Dame Enid Lyons’, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society, 2010, www.thefreelibrary.com/Faith%20and%20politics--Dame%20Enid%20Lyons.-a0322188974.

24 PR Hart & CJ Lloyd, ‘Lyons, Joseph Aloysius (Joe) (1879–1939)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lyons-joseph-aloysius-joe-7278/text12617.

25 The paper is most likely to be the Lancashire Evening Post, 14 September 1932.

26 ABC, ‘Mister Prime Minister – Joseph Aloysius Lyons’, 1966 http://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/mister-prime-minister-lyons/clip2/?nojs; S Howell, ‘A self-effacing prime minister? A look at J.A. Lyons’, 2014, moadoph.gov.au/blog/a-self-effacing-prime-minister-a-look-at-ja-lyons/, viewed 12 February 2015.

27 A Henderson & D Bird, ‘Joseph Lyons – a prime minister for modern times’, The Sydney Papers, vol. 20, no. 4, 2008, 170–87.

28 Bird, J.A. Lyons.

29 Melleuish, ‘The national character in Joe Lyons’.

30 Dame Enid Lyons, quoted in Negus, George Negus Tonight.

31 Australia, House of Representatives, 1943, Debates, 29 September, pp. 182–86.

32 J Murphy, ‘Shaping the Cold War family: Politics, domesticity and policy interventions in the 1950s’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 25, no. 105, 1995, 544–67.

33 Negus, George Negus Tonight.

34 Diane Langmore, ‘Lyons, Dame Enid Muriel (1897–1981)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lyons-dame-enid-muriel-14392/text25465; Negus, George Negus Tonight.

35 Brendan Lyons, Home Hill,p. 1.

36 Henderson, Joseph Lyons, p. 433.

37 Brendan Lyons, Home Hill, pp. 1, 9.

38 Oral history evidence, Faye Gardam, Home Hill archive, 18 February 2010.

39 Devonport City Council, Home Hill Strategic Plan, 2009, p. 4.

40 Negus, George Negus Tonight.

41 Oral history evidence, Peter Lyons (junior), Home Hill archive, 9 May 2008a.

42 C Baron, ‘Understanding historical thinking at historic sites’, Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 104, no. 3, 833–47.

43 Dame Enid Lyons, So We Take Comfort, p. 140.

44 Oral history evidence, Brendan Lyons, Home Hill archive, 2 May 2008b.

45 L Young, ‘A woman’s place is in the house … museum: Interpreting women’s histories in house museums’, Open Museum Journal, vol. 5, 2002, 1–23 (p. 17).

46 Young, ‘A woman’s place’.

47 FT King, Feeding and Care of Baby, Macmillan, London, 1913; D Deacon, ‘Anne Henderson, Enid Lyons’, book review, Australian Journal of Political Science,vol. 45, no. 2, 2010, 304.

48 Museums Australia, ‘Communicating and caring for the heritage of all Australians’, submission to the Australian Heritage Strategy review, 15 June 2012, Canberra, p. 29.

49 L Young, ‘Interpretation: Heritage revealed’, Historic Environment, vol. 11, no. 4, 1995, 4–8 (p. 4).

50 Davison, The Use and Abuse of Australian History, pp. 105, 117.

51 C Smith, ‘The house enshrined’, PhD thesis, University of Canberra, 2002.

52 Young, ‘A woman’s place’, p. 8.

53 S Malloy, ‘Home, community and public history: The shaping of three Australian prime ministers – Joseph Lyons, John Curtin and Ben Chifley’, conference paper, International Conference in Contemporary Cultural Studies, Singapore, 24–25 Nov. 2014, p. 4.

54 Commonwealth Government, Report of the National Estate (The Hope Inquiry), Australian Government Printing Service, Canberra, 1974.

55 K Christensen, ‘Ideas versus things: The balancing act of interpreting historic house Museums’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol. 17, no. 2, 2011, 153–68.

56 JF Donnelly (ed.), Interpreting Historic House Museums, AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Walnut Creek, CA, pp. 1–2.

57 L Bedford, ‘Finding the story in history’, in DL McRainey & J Russick (eds), Connecting Kids to History with Museum Exhibitions, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA, pp. 97–116.

58 Devonport City Council, Home Hill Strategic Plan. pp. 3, 5, 8.

59 M Tiers, ‘Panels will help tell Chifley story’, Western Advocate, 30 Dec. 2009.

60 Australian Curriculum and Reporting Authority (ACARA), Australian Curriculum: History, ACARA, Sydney, 2009, p. 15.

61 C Marsh, Studies of Society and Environment: Exploring the Teaching Possibilities, Pearson Education, Frenchs Forest, NSW, 2008, p. 271.

62 Scootle is an online national professional learning network for Australian educators.

63 ACARA, Australian Curriculum: History, ACARA, Sydney, 2009.

64 Commonwealth Government, Museums in Australia 1975: Report of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (Pigott Report), Australian Government Printing Service, Canberra, par. 12.6.

65 J Fritsch, Museum Gallery Interpretation and Material Culture, Routledge, New York & Abingdon, Oxon, 2011. See also L De Santis, ‘Once upon a time … interpreting the past for young children’, in R Black & B Weiler (eds), Interpreting The Land Down Under: Australian Heritage Interpretation and Tour Guiding, Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, Colorado, 2004, pp. 73–91.

66 Davison, The Use and Abuse of Australian History, p. 125.

67 M Somerville, ‘Place pedagogies’, Australian Journal of Language & Literacy, vol. 30, no. 2, 2007, 149–64. See also, G Smith, ‘Place-based education: Learning to be where we are’, The Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 83, no. 8, 2002, 584–94; M Green, ‘From wilderness to the educational heart: A Tasmanian story of place’, Australian Journal of Environmental Education, vol. 24, 2008, 35–43.