Abstract

This article surveys the work of Michael Aird, Queensland photographer, anthropologist and curator. Over the past 25 years, Aird has produced numerous exhibitions and publications focused on photographs of Aboriginal people, including Portraits of our Elders, Brisbane Blacks, Transforming Tindale, Object of the Story and Captured: Early Brisbane Photographers and their Aboriginal Subjects. He also continues to assemble a remarkable archive and create photographs himself. Photographs are at the centre of a personal working method that involves continuous, extensive sharing and discussion of images with families and communities and a forensic examination of photographs themselves. In contrast to interpretations of photography as exploitation and objectification of Aboriginal people, Aird’s work explores how Aboriginal people perceive themselves and their ancestors in photographs, ‘looking past’, as he puts it, the intentions of colonial and scientific gazes to articulate lived experience and agency.

Introduction

In discussing the transformation of photography in the hands of Aboriginal practitioners, curator Djon Mundine writes that:

for most of our history we were at the ‘victim’ end of the lens … previously photographic images of us had in fact become substitutes for us. Photography as an art practice in Australia changed profoundly between 1971 and 1990, from a type of documentary ‘craft’ to develop to be seen as an intelligent, deeply analysed ‘read’ artwork by 1990.[1]

He thus encapsulates a fundamental shift that encompasses the recognition and deployment of the activist potential of photography in the 1970s, a concurrent critique of the production and circulation of images of Aboriginal people and their cultural practices by museums, anthropologists and others, alongside the emergence from the early 1980s of new generations of contemporary artists exploring issues of identity, race, power and self-determination through diverse aesthetic strategies, including particularly innovative uses of photography. As Mundine also observes, photography was a ‘tool of colonialism, a tool with which to label, control, de-humanise and dis-empower its subjects who could only reply in defiant gaze at the lens controlled by someone-else’.[2] Other Indigenous scholars and activists have used similar terms to account for the relationship between Indigenous peoples and collections. Henrietta Fourmile, for example, describes Aboriginal people as ‘captives of the archives’.[3] Queensland photographer, anthropologist and curator Michael Aird references, but also challenges, this line of reasoning in his recent exhibition Captured: Early Brisbane Photographers and their Aboriginal Subjects, presented at Museum of Brisbane from March to June 2014.

Captured is the latest in a series of exhibitions, publications and projects produced by Aird over the past 25 years, a body of work that demonstrates the impact and importance of sustained, tenacious research and personal engagement in bringing Aboriginal agency to the fore in interpreting photographs.[4] As well as amassing and analysing an extraordinary archive, Aird is a photographer who documents contemporary Aboriginal life, creating on multiple fronts a distinctive vision that resists and complicates arguments that see photography only in terms of the exertion of power. Along with other artist/curators such as Tracey Moffatt and Brenda L Croft, Aird is part of a vibrant Aboriginal photography movement that is reframing and redefining both archival photography and contemporary practice. For Aird, ‘history began with the invention of photography’,[5] and his work positions photographs of Aboriginal people as living, relational objects, which exist as part of dynamic relationships within Aboriginal communities and between generations of families. In bringing these to light in exhibitions and books, Aird creates spaces for exchange and enables contemplation of a shared existence that has been too often simplified and trammelled into discourses of subjugation and victimisation. The blended sensibility of artist and archivist makes Aird’s work a unique offering.

Portraits of our Elders – the foundation

Aird’s first exhibition in a public museum was Portraits of our Elders, based on studio photographs of Aboriginal people from 1860 to 1925, and shown at the Queensland Museum in 1991. It went on to tour for a further five years from 1993 and was accompanied by a publication of the same name.[6] The exhibition foreshadowed the key themes that continue to preoccupy Aird: grounded in family, with images sourced from private and public collections that trace generations of families of south-east Queensland, including his own. Portraits of our Elders was also grounded in place, using photographs to locate Aboriginal people in the landscapes they had begun to share with interlopers. The exhibition and catalogue also reveal an intense interest in what Christopher Pinney calls ‘the photographic event … the dialogic period during which the subject and the photographer come together’.[7] Aird explores the motivations and sensibilities of both parties as well as the technologies of the exchange: the time and stillness needed by the cameras of the time to create a clear image; the neck clamps and chair braces that controlled the bodies of subjects to achieve this clarity; the clothing, breastplates and jewellery they wore, or conversely, the subjects’ nakedness; and the props and painted backdrops that created stages for the performance of Aboriginal life as conceived by the photographers. He also seeks to correct misinformation and find answers by meticulously studying the photographs themselves. Portraits also presented a second type of studio photograph: those commissioned by Aboriginal people in the early 20th century as they sought recognition of their resilience and success in the terms of settler society that they themselves also valued: independence, respectability, self-reliance. The contrast between these two kinds of photographs is striking and disallows simplistic interpretation of the meanings of these images. Importantly, the exhibition stressed the meanings for Aboriginal people. As Aird contends, many Aboriginal people ‘look past the stereotypical way in which their relatives and ancestors have been portrayed’ and positively interpret the photographs for themselves.[8]

photograph by Peter Hyllested, courtesy Doris Yuke Collection

Overall, the tone of Portraits is deeply respectful, even reverential. Aird accords the old people a tender esteem and foregrounds their humanity. This tone imbues all his subsequent projects and Portraits can be seen as a founding statement, which sets the parameters of Aird’s body of work. It is highly significant that this was a project instigated and delivered with freedom by an Aboriginal curator at a time when few Indigenous people were employed in the Australian museum sector. Aird has reflected that ‘this was most likely the first time a state museum or gallery produced an exhibition that was initiated by an Aboriginal curator … prior to this a few major galleries and museums had involved Aboriginal people in curatorial teams but always in projects that had been initiated and controlled by non-Aboriginal curators’.[9] As recently as 2008, the editors of the volume The Makers and Making of Indigenous Australian Museum Collections made the observation that ‘it is evident that much remains to be said about museum collections, particularly in relation to photography’.[10]

Aird’s research into Queensland Museum’s photographic collections began in 1990. He worked there as curator from 1995 to 2000, and he is back there again, developing a new permanent exhibition. Such a sustained engagement with a specific collection is increasingly uncommon in Australian museums and in Aird’s case has expanded to photographic collections across the world. Together with other researchers, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, Aird’s work is opening new pathways to alternative ways of seeing photographs and photographic collections and revealing the distinctive ways they are perceived by Indigenous people.[11]

Keeaira Press: ‘the large community family’

In 1996, Aird established Keeaira Press with the publication of I Know a Few Words: Talking about Aboriginal Languages. While it is foremost a book about language revitalisation, this early publication signals how intrinsic photography is to all of Aird’s endeavours, regardless of subject matter.[12] The book features photographic portraits of people alongside personal accounts of language knowledge and use. Reflecting back on the project, Aird has argued that the inclusion of images diffused the politics of the project by allaying tensions about intellectual property. In conveying the interconnectedness of language, people and place through images, the photographs materialised connections that obviated the need to state them in didactic terms, a strategy that continues to inform his work. Aird then went on in 2001 to publish the book Brisbane Blacks, yet to be surpassed in its documentation of the richness and vitality of urban Aboriginal life in Australia.[13] Brisbane Blacks was initiated by the Brisbane City Council, but developed via an intense collaborative effort with community members, and which had photographs at its core. To start the project, Aird assembled a folder of about 100 photographs, chosen with an idea of ‘who could speak for the photograph’,[14] as well as the specific interpersonal, community and family connections associated with each image. He then began meeting with people and showing them photographs, recording the conversations and stories that came forth. After each meeting, he would transcribe the interview and then lay it out with the images, creating a physical representation of the conversation that he would then take along to the meeting with his next informant. Participants often then brought out photographs from their own collections and Aird also photographed people throughout the process. Thus the book emerged from the layering of conversations around photographs and the making of photographs. As Aird puts it, ‘people could see where the book was coming from … it was what they knew, what was familiar, what was real life.’[15]

photograph by Michael Aird, published in Brisbane Blacks

Brisbane Blacks comprises interviews with 55 people, with a further 200 people providing comments and feedback. Images balance text, with first-person accounts bringing history alive in vivid, fine-grained depictions that were a revelation to many. Lord Mayor of Brisbane, Jim Soorley, wrote in the foreword, ‘One of the remarkable things about the extraordinarily rich Aboriginal heritage centred around the Moreton Bay region is how little the wider community knows of it’.[16] The book’s combination of imagery and voice reflects Elizabeth Edwards’ account of how photographs are ‘enmeshed’ in a matrix of personal, family and community histories for Aboriginal people: they are embodied, relational objects that are used to ‘tell history’ in the context of relationships and which recuperate and perform identities, becoming a ‘form of extended personhood’.[17] The photographs and stories in Brisbane Blacks range across all aspects of people’s lives, conveying a holistic sense of identity that encompasses history, politics, art, education, family, work, sport, music, socialising and more. The inclusion of a CD of the iconic song by local country rock band Mop and the Dropouts, which gives the book its name, reinforces this.

The book feels like a conversation, yet Brisbane Blacks is dense and invites close reading for those unfamiliar with the communities documented. For others, who are part of the meshwork of relationships that connect the stories, the book was no doubt long overdue as a telling of their histories. It is also generous in its coverage. As Aird has written, many Aboriginal people are seeking recognition of their families through the exhibition, publication and exchange of photographs; ‘to see the story told of how wonderful their parents and grandparents were, people who achieved so much through difficult and changing times – people who struggled to stay in their traditional country and keep their families together, while also living with the ever-present threat of government intervention’.[18] The book articulates a strong determination to control the way Aboriginal people are represented and stakes a claim for historical narratives of strength, vitality, community cohesion, support and celebration. It is when faced with an assembly of so many images of smiling, confident people that the dominance of other forms of representation becomes so starkly obvious. As Jane Lydon has argued, there is a long history of depicting Aboriginal people as abject for a range of purposes: ‘Images revealing Aboriginal suffering have been used to suggest the need for intervention into Aboriginal lives, to shore up the status quo, and to fuel “benign whiteness” – the assumption that white identity and mainstream values are naturally the standard to which others should conform’.[19] In this historical context, representation has critical political and social effects, as does the viewing and interpretation of images. As viewers, we have responsibilities too. As Lydon puts it, ‘Instead of viewing others as objects of concern, we must instead view them as subjects of rights’.[20] In concluding the book with the chapter ‘Marching for our rights’, Aird reminds us that this is something Aboriginal people in Brisbane have been demanding for a long time.

Transforming Tindale

Questions of representation and interpretation were central to another highly significant project, the 2012 exhibition Transforming Tindale at the State Library of Queensland (SLQ), which Aird curated with artist Vernon Ah Khee. The ‘Tindale’ of the title is Norman Tindale, the renowned anthropologist whose research for the South Australian Museum from the 1920s onwards resulted in his 1974 map and catalogue of Aboriginal tribal boundaries, as well as an extensive collection, which is inscribed in the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World register.[21] The exhibition concerned the photographs and other material collected during the joint Harvard–Adelaide Universities’ Anthropological Expedition of 1938–39 by Tindale, his American colleague Professor Joseph Birdsell and their wives. It focused in particular on genealogies and photographs of more than 1100 people from five Queensland and two northern New South Wales Aboriginal communities. Heather Goodall has described it as one of ‘the most famous of the settler/scientific photographic archives’ in Australia. From the 1980s Aboriginal people advocated for it to be released for use by individuals and communities, not just scholars.[22] The photographs are often described as ‘mugshots’ as they depict individuals, sometimes pairs of people, staring directly at the camera and from the side, reflecting the prevailing scientific interest in physical anthropology. Transforming Tindale was not about Tindale’s scientific intentions, however, but explored how Aboriginal people encounter the photographs today. As Ah Khee has commented, ‘My greatest hope for the exhibition was that it would be about our families, not about Tindale and not about anthropology’.[23]

Despite unease about the way people are depicted in the collection, Aboriginal people have been very keen to access the photographs, because they are often the only images available of certain family members, due to their lack of freedom and enforced poverty living ‘under the Act’ on Queensland government reserves.[24] Ah Khee recounts how his grandmother carried tiny copies of Tindale’s photographs of her mother, father and husband in her purse and how, with this memory in mind, he sought copies of the images from SLQ when he moved to Brisbane in the 1990s. In the early 2000s he obtained high-resolution digital scans of the original negatives from the South Australian Museum, which provided a new level of detail and revelation. He used these as the basis for the remarkable series of large-scale drawings titled neither pride nor courage that formed a prominent part of Transforming Tindale. In the series, Ah Khee supplements his drawn interpretations of the Tindale photographs with portraits of his children. Alongside Ah Khee’s artworks, the exhibition featured a selection of 200 small and 36 large double-format photographs from the collection, extracts from written material that accompanied the photographs, and quotes from contemporary family members of those depicted. It also included filmed interviews with Aird and Ah Khee and some contextual information about Tindale, the expedition and anthropological practices.

photograph by Michael Aird

The presentation of the exhibition was strongly contemporary, the room was a striking tone of citrus green and the black and white photographs were presented in square format and greatly enlarged from their original size. Text was applied directly to the walls, and included handwritten field notes and extracts from genealogies. The overall effect was more like a contemporary art exhibition than a traditional social history presentation. The photographs were transformed into artefacts, each demanding full attention as viewers found themselves looking directly into the eyes of a life-size person. Similarly, Ah Khee’s works focus powerfully on the gaze of the individuals he depicts; his drawings highlight the ambiguity of the images and the tension between the intentions of the anthropologists, the circumstances of people’s lives and their subjectivity as distinct individuals:

There’s this gaze that’s consistent through all the subjects because they’re basically in confinement and made to sit. And on some of the communities they’re very much under the thumb or under the heel actually. And so there’s this gaze and you know as an artist, and as a black fella, and as a critical thinker, I read lots of ideas, and emotions and connotations into the gaze and I wanted to pursue that.[25]

Being in the exhibition space was to be in the presence of real people, the materiality of the images somehow transcending photography’s tendency to fix time and space. In this sense, the decontextualising tendencies of exhibitions were used to advantage as the curators redefined a new context for these images as portraits of people rather than scientific objects. Aird described the research process as ‘getting to know 1100 people and connecting with other people through them’.[26] He immersed himself in the photographs, studying the subtle details of each image and, as with his previous work, spent six months on the road talking about the photographs, visiting communities across Queensland, including Mona Mona, Townsville, Cairns, Mareeba and Palm Island, as well as many families in the south-east, sharing the photographs and seeking permission to use them in the exhibition. This meant that the exhibition was more than an event – it was an active process of revisiting the meanings of these images with hundreds of Aboriginal people in Queensland, many of whom were able to provide important information about the people in the photographs and the circumstances of the photograph being taken. By the 1930s, mass market cameras were widely available in Australia but not necessarily on reserves in Queensland, especially in the far north. For some people, this was the first time they had seen images of particular relatives. Aird believes that uniting these images with families ‘gives strength to people’ and grants them a place in history: ‘this is where we fit in and here’s the proof’.[27] It is a practice of deep reciprocity.

photograph by Michael Aird

Aird has described this process as a ‘responsibility’, of being ‘entrusted’ by individuals and communities to access their histories by engaging with the formal systems of archives and collections:

I’ve had to learn the systems, ask nicely. But it’s an honour and a privilege to see the stuff. I wanted access so I could share what was in there with other people. Hopefully access will improve in the future as its been clouded with racist, scientific stuff. But people look past the racism and see family.[28]

The community life of these images was palpable at the exhibition opening when, amidst the extraordinary energy roused by the exhibition, family members posed for new photographs alongside the historical depictions of their relatives.

Transforming Tindale also inspired a series of public programs, notably a one-day symposium, The Legacy of Tindale: Photography and the Politics of Anthropology and Native Title, which was timed to coincide with the Australian Anthropological Society conference held at the University of Queensland, and talks that were presented as part of the Brisbane Writers Festival. The willingness to engage with diverse audiences is another hallmark of Aird’s work. Although he works in a freelance capacity, Aird’s exhibitions are clearly authored by him and, as such, he has built an audience that follows his work, whether it is located in state institutions or local and regional galleries. Through talks, tours and media work, Aird has opened a space of dialogue where people are able to ask questions that may previously have been uncomfortable: Who are the people in these photographs? Why are the photographs taken in this way? What do the photographs tell us about the relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people over time? Are the subjects of these photographs victims? Located at the heart of Queensland’s Cultural Centre at Southbank for three months and now touring in reduced form to the state’s local libraries, Transforming Tindale has been a watershed moment in Queensland’s exhibitionary history. By opening up such an important collection to scrutiny, particularly to analysis by Aboriginal people themselves, and facilitating rich and varied conversations about it, the exhibition marked a level of insight and creative response rarely reached in Queensland museums.

photograph by Michael Aird

The place of art

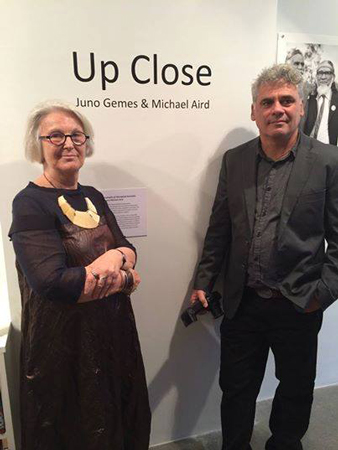

Aird’s own photographic practice remains an important component of his work. Although he perceives it as documentary in nature, much of it is exhibited in art galleries: in the travelling exhibition Cold Eels and Distant Thoughts, curated by Djon Mundine and in Woogoompah: My Country – Swamp Country at the Gold Coast City Gallery, both in 2011, for instance. More recently, his work featured in My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia at Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art in 2013, and he exhibited with Juno Gemes at Rebecca Hossack Gallery in London in 2014. The work is inseparable from his ongoing exploration of and response to historical photography, as his ‘artist statement’ for Woogoompah shows:

For many years I have been conscious of the types of images that are often missing from the photographic record … looking back at most people’s photo albums, you may not see too many images of people doing what they normally do on an ordinary day in their lives. Simple things like sitting around a campfire or walking through a mangrove mudflat or a shallow creek at low tide, to me are all worthy of being photographed.[29]

courtesy Juno Gemes

This historical consciousness can be attributed to his family. Aird was taught photography by his mother and he’s been told of how his grandmother developed photographs in her kitchen at night. His wider family has an exceptional archive that has inspired his work and which he continues to draw on. His mother’s auntie Doris Yuke’s collection, for example, has images dating back to the 1890s, which show the everyday life of families, including family groups both in studio and domestic settings and snapshots of working and private lives. Extending this family practice, he has said that his aim is ‘to put ordinary people on the wall or in a book, people who would otherwise never get there … and to document (events) for others who can’t be here. It’s a privilege to be here and I want to share that with others who can’t be’.[30]

Aird’s work is also strongly situated within the close-knit, vibrant south-east Queensland contemporary Indigenous art scene. The work of the Campfire Group of the 1990s, the proppaNOW collective and many others demonstrates just what a fertile discursive and creative space exists in Queensland, with many artists – Ah Khee, Fiona Foley, Judy Watson, Archie Moore, Michael Cook, Tony Albert, Andrea Fisher and more – exploring historical sources in varied ways. Aird’s work has a strong artistic sensibility, but unlike these other artists, who appropriate, critique and reframe historical sources, he maintains a fidelity to history and photography’s indexical role, perceiving his own work as both continuing and contemporising established practices of documentation.

Taking care

By incorporating objects, the 2013 exhibition Object of the Story: Reflections on Place at the Northern Rivers Community Gallery in Ballina, northern New South Wales, signalled both a return and an intriguing new direction for Aird. Working with fellow photographer Mandana Mapar, Aird explored the deep emotional connections between objects, people and place, echoing Sherry Turkle’s concept of evocative objects: ‘We think with the objects we love; we love the objects we think with’.[31] Just as in I Know a Few Words, Object of the Story uses photographs to materialise these abstract connections but explicitly explores them through emotion. The curators explain that ‘the photographs taken specifically for this exhibition document the emotions and memories that arise from holding these objects close and contemplating the milestones throughout a person’s life’.[32] Aird’s and Mapar’s photographs are presented alongside photographs and objects from people’s personal collections. Again, photographs are conceived of in a material sense, as containers of memory that have an active existence in people’s lives. Stories come forth from objects and photographs alike: an axe, a boomerang, a showground prize, a surfboard, artworks, framed photographs, snapshots and the remnants of a photo album that survived both flood and fire. Stories of home, movement between places and staying put, of community and personal achievements, of surfing, debutante balls and football. A vivid depiction of place emerges, imbued with the feelings that accompany looking at photographs and remembering.

The depth of emotion that photographs evoke is what Roland Barthes seeks to capture in his term ‘punctum’, the non-rational quality or element that ‘pierces’ the formal content – meaning, subject, context – of a photograph, or what Barthes calls the ‘studium’. Barthes describes the punctum as a ‘wound … that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)’.[33] Barthes is referring to the private meaning that an individual experiences in response to photographs, a meaning that is difficult to express in language. The participatory processes involved with both Object of the Story and Transforming Tindale sought to draw out these deeply held feelings so that, through the photographs, people could make links between their personal memories and larger social histories and national narratives, claiming space and even promoting healing.

The process of activating memory in a community through personal collections differs from that of taking an institutional collection to communities yet both involve the careful negotiation of feelings. With institutional collections like the Tindale photographs, people have to deal with the dehumanising effects implicit in the images, and are reminded of the difficult circumstances endured by their family members in earlier times. Locating and drawing out memories in community collections can give rise to expressions of pride but also sadness, loss and countless other feelings. The role of the curator in these situations literally involves caring for people as they go through these emotions, as well as taking care of the situations in which the exchange takes place.[34] Aird acknowledges that this work ‘takes a lot of time’, is ongoing and depends entirely on establishing trust and maintaining good will. It requires fluency and respect, and exemplifies a way of working with collections that is distinct from prescribed notions of institutional protocol and access and is instead founded in what Jackie Huggins describes as ‘the communal nature of relationships inherent in Aboriginal society: the connectedness which determines who actually does what, who has responsibility for what, who takes the responsibility for saying things to whom, who does the saying’.[35]

Captured

Captured: Early Brisbane Photographers and their Aboriginal Subjects was presented at Museum of Brisbane in 2014 as part of its Document program, ‘an ongoing series of exhibitions that uncover how artists, photographers and observers view and record Brisbane’s landscape, history and culture’.[36] With this framing, the exhibition was organised around the four earliest photographers to operate studios in Brisbane in the 1860s and 70s, John Watson, William Knight, Thomas Bevan and Daniel Marquis, each of whom created significant numbers of photographs of Aboriginal people for the burgeoning global market in colonial imagery of ‘the exotic’. It was also presented as a slice of Aird’s research, thus bringing together all five individuals as documenters of the city.

The exhibition displayed almost 50 original photographs, largely cartes de visite, and 180 reproductions from private and public collections, including the State Library of Queensland, Queensland Museum, British Museum and Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. This is the first time that such an extensive collection of such early photographs has been brought together and exhibited in Queensland - en masse, the images were breathtaking. The exhibition space called to mind traditional Queensland architecture with clear blue wall panelling and dark timber cover strips, the photographs displayed close together, in a style reminiscent of Victorian interiors. Designer Alison Ross drew on her theatre background in the creation of a box-like space occupying the centre of the room. Using projections and lighting on a gauze screen Ross evoked the sense of a 19th-century studio, as visitors peered through four openings that reproduced the four lenses of Disderi’s patented camera for producing cartes de visites.

photographs by Michael Aird

The exhibition included every photograph Aird has managed to locate by each of the photographers, rather than a curated selection. In pitching the exhibition as his ‘research at a particular point in time’, Aird argues this was a ‘democratic approach of not making one image more important than another’.[37] He also used the exhibition to correct a number of instances of misattribution, as well as presenting the resolution of long-standing puzzles, such as the photograph of a large group of people from Durundur Station, which he has now conclusively determined was taken in John Watson’s Queen Street studio.[38] Given this image appears in several collections with little information beyond a generalised caption, his research provides important new knowledge about the lives and movement of Aboriginal people in early Queensland. Aird identifies the 1860s and 70s as a particularly important timeframe, as these images depict Aboriginal people prior to the huge population influxes of immigrants in the 1880s and the introduction of the Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897, which had such profound and drastic repercussions for the majority of Queensland’s Aboriginal people. Without denying that the negative effects of colonisation were well underway, Aird conveys this period as a time when many Aboriginal people still moved freely around the nascent town and participated in new practices such as photography. He is adamant that the subjects of the images are not victims, but were aware that photography operated as part of the colonial economy. The photographic moment is cast as an exchange between people who knew each other and he contends that Aboriginal people were paid, if not always in money then with tobacco, pipes, clothing and so on. Photography was a ‘tactic of survival’ and these people, he argues, ‘don’t look as stressed’[39] as people in later photographs, such as those taken during the Tindale expedition, or once people were living with the ever-present threat of forcible removal from their country. He has identified many of the people in the exhibition and the juxtaposition of their names with the original handwritten captions (such as Australians, Queensland, Part of a Tribe and Native Blackfellow) is extremely powerful.

While Aird puts forward a strong case for seeing these subjects as historical agents, the images themselves invite other questions that are left hanging: What do we make of the staged scenes, many of which are fights or family groups? What are the relationships between the people in the photos? Did they live in Brisbane? How are these images similar or different to those being taken of colonisers? What was Brisbane like when the populations of Aboriginal people and colonisers were far closer in number?[40] Given that this period of time is well beyond living memory and is curiously neglected by the city’s museums,[41] further interpretation, beyond the basic biographical information about the photographers, may have expanded the comprehension and imaginative potential of visitors. Aird prefers, however, to use photographs to raise these questions, leaving their resolution open-ended. Perhaps this approach works to turn visitors’ minds to their own strategies of looking – why, for instance, might a visitor see these grave faces as sad, rather than strong? Just as Aboriginal people may ‘look past’ the preconceptions and intentions of colonial photography, can non-Indigenous Australians look at these images and see Aboriginal people in terms that they determine, simultaneously facing and rejecting assimilationist forces still so ingrained in Australian society?

Conclusion

Unlike critics who consider that photography’s factual status is unstable, its meanings always contingent, Roland Barthes argues instead for its ability to establish authenticity:The Photograph’s essence is to ratify what it represents … the important thing is that the photograph possesses an evidential force, and that its testimony bears not on the object but on time … in the Photograph, the power of authentication exceeds the power of representation.[42]

I suspect Michael Aird would agree with this. His work makes a strong claim for photography’s capacity to define Aboriginal history, on Aboriginal terms that are separate from contemporary politics, connected instead to an enduring social world of reciprocity, kinship and community. Aird’s research demonstrates that Aboriginal people have always engaged with contemporary media and sought to control the conditions of their representation, even in the most difficult of circumstances. His exhibitions and publications bring this insistence to public attention, prompting dialogue and continued probing. It will be fascinating to see what he uncovers next.

Endnotes

1 Djon Mundine, Brewarrina Boy, Australian Museum, Sydney, 19 March 2012, www.australianmuseum.net.au/brewarrina-boy.

2 ibid.

3 Henrietta Fourmile, ‘Who owns the past? – Aborigines as captives of the archives’, Aboriginal History, vol.13, no.1, 1989, 1–8, (p. 1).

4 A new exhibition, Wild Australia: Meston’s ‘Wild Australia’ Show 1892–1893 curated by Aird and Mapar, with Paul Memmott, opened at the University of Queensland Anthropology Museum on 20 February 2015, after this article was completed. It presents photographs by Charles Kerry, Henry King and John William Lindt in 1892 and 1893 of a troupe of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island performers taken to Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne by Archibald Meston to stage what was known as the ‘Wild Australia Show’.

5 Interview with Michael Aird, 5 May 2014.

6 Michael Aird, Portraits of our Elders, Queensland Museum, Brisbane, 1993.

7 Christopher Pinney, ‘Introduction: “How the other half …”’, in Christopher Pinney & Nicolas Peterson (eds), Photography’s Other Histories, Duke University Press, Durham and New York, 2003, p. 10.

8 ibid., p. 25.

9 Michael Aird, ‘Defining who we are’, in Djon Mundine (ed.), Queensland – Sunshine State, Campbelltown Art Gallery, Campbelltown, 2007.

10 Nicolas Peterson, Lindy Allen & Louise Hamby, ‘Introduction’, in Peterson, Allen & Hamby (eds), The Makers and Making of Indigenous Australian Museum Collections, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2008, p. 20.

11 Jane Lydon’s work is particularly noteworthy; see, for example, the recent publication edited by Lydon, Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2014.

12 Michael Aird, I Know a Few Words: Talking about Aboriginal Languages, Keeaira Press, Southport, 1996. The photographs in this book were taken by Mick Richards.

13 Michael Aird, Brisbane Blacks, Keeaira Press, Southport, 2001.

14 Interview with Michael Aird, 15 August 2014.

15 ibid.

16 Aird, Brisbane Blacks, p. 7.

17 Elizabeth Edwards, ‘Photographs and the sound of history’, Visual Anthropology Review, vol. 21, nos 1–2, 2005, 27–46 (p. 31). See also Gaynor Macdonald, ‘Photos in Wiradjuri biscuit tins: Negotiating relatedness and validating colonial histories’, Oceania, vol. 73, no. 4, 2003, 225–42.

18 Michael Aird, ‘Aboriginal people and four early Brisbane photographers’, in Lydon (ed.), Calling the Shots, pp. 133–4.

19 Jane Lydon, The Flash of Recognition: Photography and the Emergence of Indigenous Rights, NewSouth Books, Sydney, 2012, p. 281.

20 ibid., p. 283.

21 www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/collections/information-resources/archives/tindale-dr-norman-barnett-aa-338.

22 Heather Goodall, ‘“Karroo: Mates” – Communities reclaim their images’, Aboriginal History, vol. 30, 2006, 48–66 (p. 49). See also Fourmile, ‘Who owns the past?’. In the1980s, the State Library of Queensland was permitted by the South Australian Museum to hold copies for research purposes of genealogical information and photographs from the Tindale Collection for the Queensland Aboriginal communities of Yarrabah, Cherbourg, Mona Mona, Palm Island, Woorabinda, Bentinck Island, Doomadgee and Mornington Island, as well as two northern New South Wales communities at Boggabilla and Woodenbong. Access to the full information is limited and only family members of those depicted can access the photographs and genealogies.

23 www.vernonahkee.blogspot.com.au/2012/09/legacy-of-tindale-symposium.

24 The Queensland Government’s Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 and its subsequent iterations controlled the lives of Aboriginal people on government reserves until the 1980s. See Rosalind Kidd, Black Lives, Government Lies, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2000.

25 Interview, ‘Transforming Tindale: In conversation with Michael Aird, Vernon Ah Kee and Louise Denoon’, www.vimeo.com/49736545.

26 ibid.

27 Interview, 5 May 2014.

28 Michael Aird, Panel discussion for Written on the Body exhibition, University of Queensland Anthropology Museum, Brisbane, 15 August 2014.

29 Michael Aird, Woogoompah: My Country – Swamp Country, Gold Coast City Gallery, Surfers Paradise, 2011.

30 Interview, 15 August 2014.

31 Shelly Turkle (ed), Evocative Objects: Things We Think with, The MIT Press, Cambridge and London, 2007, p. 5.

32 Michael Aird & Mandana Mapar, Object of the Story: Reflections on Place, Keeaira Press, Southport, 2013.

33 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. by Richard Howard, Hill & Wang, The Noonday Press, New York, 1981, p. 27.

34 The word ‘curator’ comes from the Latin ‘curare’, to care.

35 Jackie Huggins, Sister Girl: The Writings of Aboriginal Activist and Historian Jackie Huggins, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1998, p. 32.

36 www.museumofbrisbane.com.au/whats-on/captured-early-brisbane-photographers-and-their-aboriginal-subjects/#captured.

37 Michael Aird, Curator’s talk, Museum of Brisbane, 15 June 2014.

38 See also Aird, ‘Aboriginal people and four early Brisbane photographers’, in Lydon (ed.), Calling the Shots, p. 140.

39 Curator’s talk,15 June 2014.

40 As Bill Thorpe argues, it is ‘probably impossible’ to estimate the numbers of Aboriginal people in the Moreton Bay region before colonisation. He provides figures ranging from Archibald Meston’s estimate of 16,000 to Commissioner of Crown Lands Stephen Simpson’s 1843 count of 5000. Bill Thorpe, Remembering the Forgotten: A History of Deebing Creek Aboriginal Mission in Queensland, 1887–1915, Seeview Press, Henley Beach, 2004, p. 3. The 1861 Census of the Colony Of Queensland put the white population of Brisbane at 6051: see www.qgso.qld.gov.au/products/publications/census-colony-qld/census-colony-qld-1861-sec-1.pdf.

41 The Royal Historical Society of Queensland’s Commissariat Store Museum presents the penal history of Moreton Bay, and heritage sites such as Newstead House explore specific aspects of colonial history, but neither the Queensland Museum nor Museum of Brisbane include early colonial history in their permanent exhibitions.

42 Barthes, Camera Lucida, pp. 85–9.