Australia's 'Official Papuan' collection provides a unique perspective on the shared histories of Papua New Guinea and Australia, and Australia's role as a colonial power. Collected by Sir Hubert Murray, Lieutenant-Governor of the Australian Territory of Papua, between 1907 and 1933, the collection was intended for the Territory rather than metropolitan centres in Europe or America. Its eventual journey to become part of the collection of the National Museum of Australia reflects the changing role of the collection and the influence of AC Haddon who convinced Murray that it would be under-utilised by anthropologists if it remained in Papua. This paper reconstructs the history of the Official Papuan collection, and Australian collecting in Papua during a key period in the development of anthropology.

____________________________________________________

Within the holdings of the National Museum of Australia there is a discrete ethnographic collection known as the Official Papuan collection. It stands out as an anomaly among the collections of the Museum because of its geographic origin. It differs from other contemporary collections of New Guinean material culture at the National Museum of Australia and in other institutions around the world because of the unusual length of time over which it was amassed (a period of 26 years from about 1907 to 1933), the number of people involved in making acquisitions for the collection (upwards of 50) and the widespread area over which it was collected.[1]

The Official Papuan collection comprises over 3000 objects collected from what is now Papua New Guinea. The exceptions are four woomeras and a fire-making set from Cape York. Some objects, such as a Purari Delta kaiaimunu or wickerwork figure associated with initiation ceremonies and collected in 1908 by Sir Hubert Murray, are unique examples of the earliest material removed from newly contacted cultural areas of Papua.[2] Others, such as trophy heads, are rare because government regulations were set up to discourage cannibalism and headhunting practices.[3] The majority of the objects in the collection are not rare: they could be collected with relative ease by patrol officers, resident magistrates and others in the field. However, the collection is of interest because it links stories of particular people with the nature and circumstances of the objects they collected.

The only other 'official' contemporary collection to share kinship of concept with the Official Papuan collection is Sir William MacGregor's official collection. Part of this collection is currently housed in the Queensland Museum, and part has been repatriated to the Port Moresby Museum and Art Gallery, Papua New Guinea.[4] The MacGregor collection, however, was collected personally by MacGregor over only ten years (1888-1898) and includes natural history specimens such as animal skins as well as ethnographic objects.[5]

Government officials in other colonies, such as German New Guinea,[6] the Congo,[7] Fiji,[8] India[9] and Rhodesia,[10] collected, or allowed collecting of a commercial or scientific nature to a varying extent. The nature of these collections was similar to the Official Papuan collection in that they usually included a broad range of the available material. The main difference was that the Official Papuan collection was originally intended to stay in the Territory of Papua. Many other collections acquired from colonies at around the same time were taken back to a museum, university or private collection in Europe or America.[11]

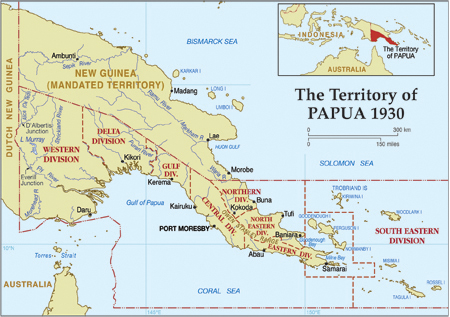

How did the Official Papuan collection come to be part of the National Museum of Australia's collection, when the charter for this museum is to record Australian social and cultural history? At first glance, a collection of ethnographic material from Papua New Guinea hardly fits this description. Part of the answer involves Australia's brief history as a colonial power. Prior to the 1880s, New Guinea (see map, above) was an area visited mostly by missionaries, traders and explorers.[12] But, none of the colonial powers had yet claimed any part of this part of the island as a colony. In 1883, Sir Thomas McIlwraith, Premier of Queensland, urged the British Government to annex or proclaim a protectorate over New Guinea.[13] By 1884, the British Government gave in to pressure from the combined Australian colonies and formed the Protectorate of British New Guinea. Administration of the Protectorate, soon after named a colony, was shared between Britain and the eastern Australian colonies of Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria.[14] By the time of Australia's Federation in 1901, Britain had decided to relieve itself of this extraneous portion of Empire, and in 1906 the Papua Act was proclaimed, handing over to Australia the responsibility and cost of running the new Australian Territory of Papua, the colony previously called British New Guinea.[15] Shortly afterwards, Hubert Murray was inducted as the Territory's first Australian Lieutenant-Governor.[16]

The story of the Official Papuan collection from its conception, through to its acquisition, storage and exhibition (in short, the biography of the collection) creates a unique view of Australia's role as a coloniser even at a time when many Australians may not have recognised the Territory of Papua as a colony.[17] The collection demonstrates the variety of connections Australia has had and maintains with Papua New Guinea, its nearest neighbour. This paper offers a brief biography of the Official Papuan collection: how and why such a collection was conceived, an introduction to how it was collected and by whom, and why it came to be part of the collections at the National Museum of Australia. It will then also consider the significance of the collection for the Museum in reflecting the shared colonial history of Papua New Guinea and Australia.

The Official Papuan collection is also known as the Sir Hubert Murray collection for its founder, the first and longest serving (1908-1940) Lieutenant-Governor of the Australian Territory of Papua. Murray is known for his interest in, and application of, anthropological and humanitarian principles to his administration of the Territory. Some researchers suggest that his interest in anthropology only extended so far as he could use it to control the Indigenous populations of the Territory. In hindsight, many of Murray's policies can be considered conservative and paternalistic, but they were considered acceptable and even enlightened at the time.[18] Regardless, it is due to the importance Murray placed on anthropology that the collection exists.[19]

Why did Murray start the collection? Firstly, it was the kind of activity in which a Governor, and man of his education and standing in the community, was expected to engage. Secondly, a popular theory of the time considered that Indigenous populations of most colonies were rapidly disappearing, and that it was the duty of those 'in charge' to maintain a record of what once was, before it was too late. Thirdly, and importantly to Murray, to collect the material culture of the Papuan people was a way to a greater knowledge of them.

When Murray first arrived in Papua (at that point still British New Guinea) to take up his position as Chief Judicial Officer in 1904, he soon realised that Papuan people perceived and acted in the world differently to Europeans.[20] In order to conduct his legal work fairly he felt he needed a better understanding of Papuans and Papuan society. In October of that year he met CG Seligman, originally a pathologist from London and later foundation Professor of Ethnology at the London School of Economics. He accompanied Seligman on his investigations at Hanuabada outside Port Moresby.[21] This serendipitous meeting was probably the catalyst for Murray's serious interest in anthropology and its potential application as an administrative tool. Until he met Seligman, Murray's collecting was limited to collecting curios on an ad hoc basis. From 1904 onwards, Murray's diary and letters to family members contain anecdotes and observations on the activities of people in various villages, the methods used in the construction of their buildings, and instances where he acquired objects through trade and as gifts. Later, as he became familiar with the anthropological literature, and met many of the anthropologists who came to Papua to conduct their research, he began to incorporate some of his anthropological observations into his publications.[22] In his diaries, he occasionally recorded situations where he had asked for specific objects to be collected. For example, in a letter to his brother George[23] in September 1906, Murray mentioned that he had asked Dona, a Motuan man, to bring back curios from the Gulf, a division of the Territory Murray then considered dangerous.[24]

In 1907, Murray decided to take the first steps in his partially formed plan to use the outcomes of anthropological research as a tool for administration. He wrote a letter to the Australian Minister for Home and Territories to gain permission to turn what was in essence his personal collection into an official one, and to establish an ethnological museum in Port Moresby in which to house it.[25] Murray gained permission for both requests, and plans were drawn up for the museum. However, it never eventuated in the form originally envisaged by Murray. For financial and other reasons discussed below, the museum was never built. Until sometime after the 1950s, the building that was referred to as 'the museum' never became much more than a storage depot for objects. The Government Anthropologist had his office in it, and Murray and others refer to taking people to view the objects in 'the museum', but the role of the building was never formalised.[26]

The various reasons Murray provided to the Minister for the creation of the collection and museum can be summarised as 'salvage'. This fitted with the persuasive views of AC Haddon, who became a Professor of Ethnology at Cambridge University and who, from around 1910, was a person of enormous influence on Murray's interpretation of anthropology. Haddon's view was that it was both an 'imperial and a scientific responsibility to record primitive cultures before their inevitable disappearance under the corrupting onslaught of Western civilisation'.[27] In his 1907 letter seeking approval for the official collection, Murray argued that many of the 'old ways', such as the ceremonies and everyday practices of the Papuan villagers, were 'passing out of use'. In the interests of science it had become urgently necessary to make collections of these things before it was too late. He also added that 'objects of special interest have passed into the hands of private collectors outside the Territory'.[28] These sentiments echoed those in a memorandum Haddon wrote to the Australian Government in 1914 on the importance of conducting anthropological research. This demonstrates that Haddon's influence in the Australian Territory of Papua began early, and as we shall see later in this paper, continued to grow.[29]

While these were the reasons Murray expressed officially, there may also have been an underlying personal reason behind Murray's desire for an official collection: his ambition to be remembered. If he intended the collection to be a tangible reminder of his governorship, he has, so far, been unsuccessful. Murray's official collection has never received much attention among the numerous works detailing his life as governor and his policies over the duration of his administration. The collection is an important but neglected and perhaps, therefore, unsuccessful symbol of Murray's attempt to incorporate anthropology into administrative practice.

Murray was also strongly influenced by Sir William MacGregor, the last long-term administrator of British New Guinea.[30] He had been widely feted for his administrative approach and successes in exploring and 'pacifying' hitherto unknown areas and people of New Guinea.[31] Unlike some of the interim administrators (between MacGregor leaving in 1898 and the proclamation of the Papua Act in 1906), MacGregor had Murray's respect on a number of levels. MacGregor was a medical doctor and man of science. His outstanding reputation as an administrator was enhanced by his scientific enthusiasm and the accompanying stories of his physical abilities while out in the field furthering the work of the Government and Science.[32] He was also an avid collector of ethnological and biological specimens, and upon retiring his position as Lieutenant-Governor, donated to the Queensland Museum a collection of around 6000 objects that he had amassed during his term.[33]

These aspects of MacGregor's character provided Murray with a challenge to his self-confidence as an administrator. MacGregor was an educated man of the Empire, hailing from Scotland, and with a reputation in administration and science: characteristics that contributed to his historical standing.[34] Murray was born in Australia, and educated in law at Oxford. At the time he became Lieutenant-Governor in 1908, he had very little administrative experience apart from his legal work as a barrister and then as circuit crown prosecutor in New South Wales. He also lacked extensive experience in dealing with Indigenous people. Because of this, and the various attacks he suffered at the hands of the Australian media and political rivals during his governorship, he felt insecure in his position throughout his career. According to his biographer, Francis West, Murray always wanted to be remembered as a 'Great Man', like MacGregor, and Governor Gordon of Fiji. Murray sought to emulate MacGregor as an administrator.[35] The Official Papuan collection was the means by which Murray began his foray into anthropology and to make his mark as a 'great administrator'.

For the most part he continued the policies of MacGregor.[36] He continued to expand the Territory, along with the various administrative structures that MacGregor had established, such as village councillors and the Armed Native Constabulary.[37] Thanks to Murray's moral view of his work, there were two specific differences in his continuation and development of MacGregor's work. He would not brook violence towards the Papuan people, and he endeavoured to integrate the 'science' of anthropology into his administrative policies. In this, the creation of his official collection had an element of 'one-upmanship' about it. The collection was not simply an extension of an intellectual hobby. It was to be specifically ethnological and to contribute to the overall knowledge of the administration. It would benefit European and Papuan alike and form an integral part of Murray's plan for a 'dual mandate'. This was a form of administration where Murray saw the Government taking responsibility for the protection and development of the interests of both Indigenous people and European settlers.[38]

With hindsight, we can take the view proposed by Nicholas Thomas that collecting in Pacific colonies by governments and missionaries was as much a demonstration of control and 'progress' as a contribution to science or any other stated reason.[39] The ability to collect and display objects promoted the idea that pacification and control of a new territory was wholly successful. Being able to remove objects of value from a 'primitive' community, and display them in an order aesthetically pleasing to Europeans, promoted the idea that the community was now an appropriately 'civilised' part of the European colony. The collection also provided evidence for newly 'pacified' people, too, that they were becoming part of the new regime. The acquisition and display of collections became a yardstick by which to measure the success of the Government.

Armed with Seligman's advice, and his own desire for posterity, Murray was responsible for the early shape of the collection. More than anything his contribution was opportunistic and haphazard. Murray appears to have collected things that provided interest to him at the time, and only if people were willing to give or trade objects. There are several instances in his diaries where he voices frustration at not being able to obtain an example of an ajiba or skull rack, although it might be assumed that people may have been more willing to give things to the Governor than to any other collector of the administration.[40] The exception to this, of course, was when he confiscated objects, specifically weapons and charms associated with homicide, inter-village warfare and 'sorcery', in his capacity as judge. This in part accounts for the large number of stone-headed clubs, spears and arrows in his collection.[41]

While Murray's 1904 meeting with Seligman introduced him to the principles of anthropological fieldwork, he had no formal training in anthropology. His ethnographic notes rarely connect his observations with the objects collected, and the objects rarely have explicatory notes attached as to from where and whom they were collected.[42] To remedy his lack of an anthropological and administrative background he continued to read the works of other colonial administrators and rising experts in anthropology throughout his career.[43] Over the years, Murray appears to have made headway with his understanding of anthropological theory as demonstrated by his confidence in publishing on popular theories of Papuan cultures as they related to his ideas on the Territory's administration.[44]

To aid in his research, Murray had at his disposal an army of collectors. In 1907, Murray's resident magistrates and patrol officers were provided with £5 per annum and what amounted to a 'shopping list' of objects for collection.[45] Presumably a similar amount was provided to fund collection in ensuing years. Along with his instructions to collect, Murray issued a warning that collecting activities were not to adversely affect the primary function (pacification and the spread of government influence) of the patrols.[46] He was concerned that the Australian Government may not have appreciated a deviation from the economic improvement of the Territory.

There was little other guidance provided to the patrol officers in terms of instructions on how and what to collect until the appointment of the first Government Anthropologist, WM Strong, in 1920. As part of the collective anthropological investigations of the administration, which were a derivative of the Notes and Queries style of field investigation, Strong provided forms with questions on specific activities within each division, which the patrol officers were then required to fill out in detail.[47] Strong's appointment was technically only part-time, as he was also the Chief Medical Officer at the same time, so much of the impact of any guidance he provided was limited.[48]

Prior to Strong, and even with his guidance as to what information to collect, the Official Papuan collection began to grow of its own accord. Here the shape of the collection was influenced by the individual inclinations of particular patrol officers. The role of a patrol officer was a combination of that of a policeman and a boundary rider on a large property. They were expected to make constant expeditions through the known parts of the Territory, and to continuously expand and strengthen the government presence at the borders of the 'pacified' areas.[49] The standing orders among the constantly changing duties of the patrol officers were to make and maintain peaceful contact with the Indigenous people and to introduce them to the idea of their new government, and its wishes and expectations.[50]

The collecting activities of individual patrol officers created a suite of unique collections within the Official Papuan collection. The following three examples, of SD Burrows, Leo Austen and RL Bellamy, show some of the diversity in collecting among the more than 50 collectors contributing to the Official Papuan collection.[51]

SD Burrows was a patrol officer between 1913 and 1920 who appears to have taken the order to collect to heart.[52] He contributed over 100 objects to the collection including cane cuirasses, various types of stone-headed clubs, arrows, necklets, food containers, waistbands, grass skirts and fire-making apparatus.[53] Some of these objects were collected while he was a member of the party stranded for five months on the government vessel Elevala at the Morehead River junction in 1914 (see map); others were from patrols around the Lake Murray area and on the Fly-Strickland River.[54] Hence, some of Burrows' collection is a specific sample of sedentary collecting, unlike most of the collection which was usually acquired while travelling through or revisiting villages. Presumably having obtained government permission, Burrows kept over 300 objects upon his resignation from the Papuan Service. After his death, his mother donated those objects via Mrs Gordon Canning to the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, in 1933.[55] Burrows therefore adds another dimension to the Australian-Papuan colonial experience: much of Murray's concern about the Official Papuan collection was to keep it within Australia or Papua, but Burrows' family instead chose to maintain links with Empire, and donate his personal collection to a British institution.

Leo Austen started in the Papuan Service in 1919 as a temporary patrol officer stationed in Daru and worked his way through a number of posts as patrol officer and resident magistrate in the Territory.[56] He was still a member of the Papuan Service in 1940 when Murray died.[57] Austen participated in two important exploratory patrols in 1921-1922 and 1922-1923.[58] One of the stated purposes of the earlier patrol was to 'obtain vocabularies and information as to the customs and habits of the natives, and to collect curios'.[59] The 1921-1922 patrol to the Star Mountains was one of the first European contacts with the area, and the 1922-1923 expedition was to further extend the territory explored in previous years.[60] During the early twentieth century, patrol officers used a range of collecting practices, but the use of force was uncommon (or at least not openly admitted to) during Murray's administration due to his strong stance against violence. Such practices included demonstrations of 'friendship', as Austen describes on 18 January 1922 in his report on the Star Mountains patrol:

| At 11.25 [am] we anchored off some native houses and went ashore. Inside were many stuffed heads, sago bags, fish nets and other odds and ends ... I did not touch anything in the shelters but left one or two old tomahawks in the hope of making friends with the people upon my return. |

Later that day he describes an instance of trade:

| We traded with these natives and procured various arrows, a stone axe, a pipe, a packet of tobacco seeds, and one or two other articles of not much value.[61] |

Austen constantly makes us aware of the fact that he is strictly adhering to Murray's protocol on non-violent contact with villagers. On 3 March he reports:

| From what I have seen of the native on the Eastern side of the Tedi, I am of the opinion that at some time or other these people have had trouble with the bird-hunters, and this is possibly the cause of their timidity ... I have no doubt however, when they see we have not looted their houses, but have actually left them valuable presents, and also that none of their people have been hurt by us, the next patrol to these parts should be able to make good friends with these natives.[62] |

However, on 8 November 1922, during his next patrol, he reports, 'Broke camp at 7:30 am, and left behind in a shelter a half-axe in payment of the shield [also described as a houseboard] which was still in this deserted house' (Fig. 2).[63] Despite his intentions to make peaceful and respectful contacts, the desire to collect clearly prompted the rather less ethical removal of material from temporarily or permanently abandoned villages. However, this method of collecting was frequently practised and considered acceptable in Papua and presumably other colonies at the time.[64]

Austen's reports on both patrols demonstrate the poor coordination within the Administration, as well as the high level of cooperation between the Papuan and Dutch administrations:

| Mr Keyzer gave me a copy of a Dutch map showing the Star Mountains and a traverse of the Alice River. As I knew nothing about Mr Burrows having made one in 1914, I gladly took it, and in return gave him a copy of the blue print of the RMWD's [Resident Magistrate Western Division] 1920 traverse of the Upper Fly River above Everill Junction.[65] |

And then:

| Since my arrival back at Daru, I have found Mr Burrows' traverse of the Alice River in 1914 This map, by the way, would have been of inestimable value to us on this patrol.[66] |

Austen saw the collection of objects and ethnographic information as a serious aspect of his job, and an important part of his future career. His publication record consists of contributions to the Territory's Annual Report, and around 10 papers in journals such as Man and the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, written with the encouragement of FE Williams, the first full-time Government Anthropologist for the Territory. Professor AC Haddon was by this time playing the role of anthropological mentor to many of the patrol officers of the Papuan Administration, encouraging them to publish their findings, and to correspond with him on matters of anthropological interest. In this way Haddon received objects and valuable information for his own research, and anthropology in Papua was brought to the attention of the British academy at regular intervals.

Another patrol officer who contributed to the Official Papuan collection was RL Bellamy. Bellamy started as an assistant resident magistrate in the Northern Division in 1904, and in 1906 was appointed Government Medical Officer and Assistant Resident Magistrate for the Trobriand Islands.[67] Bellamy's collection is unique because of his singularity of focus on object type. Between 1906 and 1915 (the date of shipment of the objects to Sydney) he collected about 20 bowls from the Trobriand Islands: Kiriwina, Massim and Mailu (Fig. 3).[68] Round or elliptical in shape, and every size from tiny to gigantic, all are similar in the rim design and pattern style for their island or region. Most of Bellamy's reports in the Annual Report of the Territory consist of medical overviews for the year, or the returns for the year as expected of a resident magistrate. Thus far, there is little information as to why Bellamy chose to collect only these objects. Later instructions to the resident magistrates and patrol officers suggest a diverse approach to object collection was preferred. It is possibly Bellamy's intense focus on just one type that caused Strong to comment in the preface to FE Williams' publication The Collection of Curios and the Preservation of Native Culture that while all efforts ought to be made to collect duplicates of objects, this should occur across districts, rather than within them.[69]

The employment of FE Williams in 1922 as a permanent Government Anthropologist saw a slightly more organised approach to recording information pertaining to each collected object, and saw collecting conducted by field officers imbued with an explicit ethical code. Williams' Collection of Curios was a kind of handbook for officers on what to be aware of while collecting, rather than specifying what to collect.[70] This included avoiding the use of force to obtain objects from individuals, not removing objects from temporarily abandoned villages, and how to identify and avoid collecting objects of great ceremonial or spiritual importance to individuals and communities.[71]

FE Williams was trained at Oxford and employed specifically for his qualifications in anthropology.[72] However, he found collecting itself a burdensome part of his work and appears to have only collected in order to represent a particular anthropological point, or possibly as a kind of meaningful 'souvenir' of a particular person, community or event. Like most officers of the administration, but unusually for an anthropologist, Williams does not record very much detail on the specifics of his collecting.

However, the objects that Williams collected provide a great deal of insight into his work. They are a physical record of the places he visited, reveal a sense of his aesthetics, and reflect the ethical principles that were so important to him.

The majority of the objects Williams collected represent 'everyday objects' in that they were largely not ceremonial: cassowary quill and pig tail earrings, arm band ornaments, and nose piercers.[73] Ironically, despite his argument in Collection of Curios to collect the least vulnerable objects, many of those he collected were quite likely to disappear first, including coconut containers, bone and stingray spine needles and fishing equipment which were all rapidly being replaced by their 'more efficient' modern counterparts. As a result, both the objects that he collected (now in the collection of the National Museum of Australia), and his ethnographies on the people and communities to which those objects belonged, form an invaluable record.

While Williams did not provide very much detail on actual collecting events, he is widely known for his ethnographic photography.[74] It may be that he felt that if an object could be represented by an image, this reduced the need to collect the actual object. For example, on 13 April 1922, he photographed nine women holding fish traps at Nomu on the beach near the mouth of the Purari River.[75] He did not collect any of the fish traps, probably both because of their size, and their continued usefulness to the villagers. On 26 April, however, he collected two piraui or fishing line floats.[76] These objects are small and light, relatively common, and made from readily obtainable materials, and would have therefore been fairly easy to replace. In comparison to a ceremonial mask, or a line of women displaying varieties of large fish traps, they were not aesthetically interesting subject matter for a photograph. The records indicate that these piraui are the first two objects collected by Williams in Papua.

The Official Papuan collection as a whole represents Murray's aim of salvaging what material culture was still available to collect during his administration: the objects cover a broad range of cultural groups, geographic locations, and object types. The collection, along with the full-time appointment of FE Williams, also represent Murray's attempts to acquire the ethnographic information required to understand how Papuan cultures worked, and thus apply this anthropological understanding to run an efficient administration. However, his reliance on a large number of mostly untrained collectors changed the style and content, what we might call the personality, of the collection, to suit the opportunities provided, the orders given, and the collectors' own interests.

By around 1914, Murray and his officers had collected so many objects that he was forced to find a new home for them. Professor AC Haddon convinced Murray that a museum such as he had originally envisaged was too expensive to maintain in Port Moresby with its difficult climate, especially as it would be underutilised by those who needed access to it most: European students of, and researchers in, anthropology.[77]

After contacting a number of institutions around Australia, and finding them lacking in various respects, Murray settled on the Australian Museum in Sydney as the new home of the Official Papuan collection. His correspondence with Robert Etheridge Jnr, the Curator, reveals that Murray resorted almost to bribery to secure storage space and curatorial care for the Official Papuan collection. Etheridge accepted a specimen of a cane cuirass from the Fly River, and the right for the ethnological curator, WE Thorpe, to select duplicates of some of the objects for the museum's own collections in return for storing and cataloguing the Official Papuan collection.[78]

Thus, between October 1915 and 1930, 12 shipments of objects were sent to the Australian Museum in Sydney.[79] WE Thorpe carefully checked each crate and object and listed them neatly and methodically in copperplate script in a large leather-bound ledger that is now called the 'Thorpe register'. In the register each object is given a 'P' (Papuan collection) number, a brief description and provenance details (where they exist). It also lists an Australian Museum registration number for those duplicated objects that the Australian Museum kept in return for the storage space. Given the enthusiasm shown by various institutions for examples of Papuan curios at the time, and therefore the competition for 'good' specimens, Thorpe was surprisingly fair in his selection of objects. A random sample of objects at the Australian Museum selected for comparison against those in the Official Papuan collection shows that those objects were indeed duplicates, or as close to such as possible, and usually not what might be considered the 'best' (oldest, newest, most complete, or least damaged depending on the item) specimen in any pair of duplicates. The duplicates kept by the Australian Museum amounted to a total of about 125 objects.[80]

By 1927, the Australian Museum was running out of space for its own collections, and Murray was once again forced to seek a new home for the Official Papuan collection.[81]

During his search for a new home for the Official Papuan collection, Murray had been in contact with Colin MacKenzie, the director of the Australian Institute of Anatomy, about housing the collection there. In further correspondence they agreed that the institute would become the next home of the Official Papuan collection.[82]

The Official Papuan collection had never been exhibited, apart from brief visits made to see the objects stored in the depot/museum/Government Anthropologist's office in Port Moresby. MacKenzie's primary focus in the Australian Institute of Anatomy was the curation and exhibition of human remains and ethnographic material to demonstrate 'evolutionary sequences'.[83] For the first time, the whole collection was displayed and 'available to scientists who wish[ed] to obtain an intimate knowledge of the culture of the Papuan natives'.[84] The plan of the open shelves in the ethnographic gallery of the institute in 1984 indicates that it had space limitations of its own; and location information recorded about each specimen while in the institute seems to indicate that much of the collection was stored in cabinets and drawers under the glass cases, and therefore available for display to scientists, rather than on constant open display to the public.[85]

No further additions were made to the Official Papuan collection after its move to Canberra in 1933. It is not entirely clear why collecting appears to have slowed at this time, except that in anthropology generally, objects were becoming less of a focus of study, and so too, they probably became less important for Murray. The orders given to the field officers of the Papuan Administration were probably not withdrawn until some time after Murray's death. What was collected probably continued to be stored in the 'museum' in Port Moresby until a suitable occasion arose to dust it off. The first such occasion was the 1938 Sydney Exhibition in honour of the 150th Anniversary of New South Wales. Of the objects sent to Sydney for the Papuan Government stall, some were sent back and others kept by the Australian Museum and the Institute of Anatomy. The National Museum of Australia now holds a number of ill-defined collections of material sent for similar exhibitions and promotional tours in 1938, 1957, 1958, 1959 and 1962. Along with their respective date identifiers, these are known as Department of Territories collections.[86]

The contents of the Australian Institute of Anatomy were subsumed by the National Museum of Australia when it was established by an Act of Parliament in 1980. The collection has mainly been in storage since it was moved from the Institute of Anatomy. The recent Captivating and Curious exhibition which opened at the National Museum of Australia in December 2005 allowed a brief outing for one of the eharo masks from the Gulf of Papua, but other than this, very little of the main collection has been on public display since it was at the institute.

Like many contemporary ethnographic collections, the Official Papuan collection reflects the personal interests and different areas of expertise of those who contributed to it. Its acquisition was guided by Sir Hubert Murray and influenced by Haddon and other British anthropologists whose ideas prevailed at the time. It was also intended to stay in Papua New Guinea and belong to the Papuans.

This paper has provided some examples of the diversity of objects, range of people, and means of collecting used in the acquisition of the Official Papuan collection to demonstrate the significance of the collection as a part of the major collections of the National Museum of Australia. The collection is not simply a representation of what was available in Papua between 1907 and 1933, it also provides us with a view of Australians as colonists. In this light, the Official Papuan collection tells as much about Australia's past as it does about Papua New Guinea's.

The collection forms a tangible representation of the morals, ethics, and aspirations of Australians in Papua in the first half of the twentieth century. While the Official Papuan collection in the National Museum of Australia might not meet the aspirations Murray once held for it, the history of the collection demonstrates that what began as a story about objects, is becoming in essence a story about the entangled histories of the people of Australia and Papua New Guinea.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

1 Much ethnographic collecting up to and during the early 1900s was confined to large organised scientific and/or exploratory expeditions such as the 1898-1899 Cambridge Torres Strait Expedition whose ethnographic collection resides in the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. These expeditions consisted of a flotilla of experts who would gather data from limited areas during a limited time frame. See for example A Herle and S Rouse (eds), Cambridge and the Torres Strait Centenary Essays on the 1898 Anthropological Expedition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989. V Ebin and DA Swallow (eds), 'The Proper Study of Mankind ...': Great Anthropological Collections in Cambridge, Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge, 1984 describe the collections of CUMAA. There were also a number of smaller expeditions, and individuals who often collected intensively from a particular group of people or region, on behalf of a museum or other benefactor. An example is AB Lewis (fieldwork in New Guinea 1909-1912) whose collection of some 14,000 objects is at the Field Museum, Chicago. There were also people who collected as an aside to other work in order to sell objects to collectors and institutions. Various religious missions acquired collections as well. However, these are outside the scope of this paper.

From about 1920, following Bronislaw Malinowski (three trips to New Guinea between 1914 and 1918), it became imperative for anthropologists to conduct extended fieldwork while living among the people they had chosen to study. Examples include Beatrice Blackwood who spent time in the Solomon Islands (1929-1930) whose collection is now at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, and Alexander Todd, a student at Sydney University who conducted fieldwork in New Guinea from 1933-1936. For more on these collectors see J Cousins, The Pitt Rivers Museum: A Souvenir Guide to the Collections, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, 1992, and C Gosden, 'On his Todd: Material culture and colonialism' in M O'Hanlon and RL Welsch (eds), Hunting the Gatherers, pp. 227-251.

2 Annual Reports of the Territory of Papua: 1905-1940, Edward George Baker, Government Printer, Port Moresby, report from 1908-1909.

3 B Craig, 'The Melanesian collections of the National Museum of Australia', Bulletin of the Conference of Museum Anthropologists, vol. 25, 1993, p. 18.

4 Sir William MacGregor was Administrator of British New Guinea from 1888-1895, and Lieutenant-Governor from 1895-1898. See Jinks, Biskup and Nelson, Readings in New Guinea History, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1973, p. 50.

5 For details on MacGregor's collection, see M Quinnell, '"Before it has become too late": The making and repatriation of Sir William MacGregor's Official Collection from British New Guinea', in M O'Hanlon and RL Welsch (eds), Hunting the Gatherers: Ethnographic Collectors, Agents and Agency in Melanesia 1870s-1930s, Berghahn Books, New York, 2000, pp. 81-103.

6 For further information on collecting in German New Guinea, see R Buschmann, 'Exploring tensions in material culture: Commercialising ethnography in German New Guinea', in M O'Hanlon and RL Welsch (eds), Hunting the Gatherers, pp. 55-81.

7 For a summary of the history of collecting in the Congo see E Schildkrout and CA Keim, 'Objects and agendas: Re-collecting the Congo', in Schildkrout and Keim (eds), The Scramble for Art in Central Africa, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998, pp. 137.

8 For more on the colonial involvement in Fiji, including collecting, see N Thomas, 'Material culture and colonial power: Ethnological collecting and the establishment of colonial rule in Fiji', Man, vol. 2, no. 1, 1989, pp. 41-56; N Thomas, 'From present to past: The politics of colonial studies', in Colonialisms Culture: Anthropology, Travel and Government, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1994, pp. 11-33.

9 For further information on collecting and exhibitions in colonial India see C Breckenbridge, 'The aesthetics and politics of colonial collecting: India at world fairs', Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 31, no. 2, 1989, pp. 195-216.

10 L Schumaker, 'A tent with a view: Colonial officers, anthropologists, and the making of the field in Northern Rhodesia, 1937-1960', Osiris, 2nd series, vol. 11, Science in the Field, 1996, pp. 237-258, deals with field officers in colonial Rhodesia.

11 M Quinnell, '"Before it has become too late"'.

12 ibid., p. 82.

13 B Jinks, P Biskup, and H Nelson (eds), Readings in New Guinea History, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1973, p. 32.

14 M Quinnell, '"Before it has become too late"'.

15 B Jinks, P Biskup, and H Nelson (eds), Readings in New Guinea History.

16 F West, Hubert Murray, pp. 98-99.

17 H Nelson, 'Never a colony', in Taim Bilong Masta: The Australian Involvement with Papua New Guinea, Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney, 1982, pp.11-22.

18 D Griffiths, 'The career of FE Williams, Government Anthropologist of Papua 1922-1943', MA thesis, ANU, Canberra, 1977; G Gray, 'Being honest to my science: Reo Fortune and JHP Murray 1927-1930', Australasian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 10, no. 1, 1999, pp. 56-76; AM Healy, 'Paternalism and consultation in Papua 1880-1960', ANU Historical Journal, no. 4, 1967, pp. 19-23 all offer criticisms of Murray and his policies. F West's biography Hubert Murray provides a contrasting view.

19 F West, Hubert Murray, looks at Murray's principles of anthropology as a tool of government.

20 ibid.

21 JHP Murray, Letter to Mary Murray, 24 October 1904, in F West (ed.), Selected Letters of Hubert Murray, p. 33; M Young, Malinowski - Odyssey of an Anthropologist, 1884-1920, Yale University Press, 2004, p. 160.

22 JHP Murray, Diaries 1904 to 1917, Sir H Murray Diaries and Papers vols 1-5, Mitchell Library A3139 (MLMP).

23 George Gilbert Aime Murray was professor of Greek at Oxford and in his public and professional life he was 'Gilbert'. He was 'George' to his brother.

24 JHP Murray, Letter to George from Port Moresby, 11 December 1906, National Library of Australia (NLA) Murray Family Papers 565/320.

25 JHP Murray, Letter to Minister for Home and Territories, December 1907, National Archives of Australia (NAA) A1 1921/24811A1 1921/24811.

26 Craig, 1993, p. 17; D Griffiths, 'The career of FE Williams, Government Anthropologist of Papua 1922-1943', MA thesis, ANU, 1977; JHP Murray, Diaries 1904 to 1917.

27 M Young, Malinowski - Odyssey of an Anthropologist, 1884-1920, pp. 157-8. This view later became known as 'salvage anthropology'.

28 JHP Murray, Letter to Minister for Home and Territories.

29 AC Haddon, 'An ethnologist for Papua', 1914, NAA A452 1959/4708.

30 MacGregor was Administrator of British New Guinea from 1888 to 1898. When MacGregor left New Guinea he became the Governor of Queensland. See M Quinnell, '"Before it has become too late"'.

31 F West, Hubert Murray.

32 It was not until 1914 when Haddon inspected MacGregor's collection that it was noted that some of MacGregor's specimens lacked vital labelling and contextual information (AC Haddon, 'An ethnologist for Papua'). See also M Quinnell, '"Before it has become too late"'; F West, Hubert Murray.

33 M Quinnell, '"Before it has become too late"'.

34 F West, Hubert Murray.

35 ibid.; JHP Murray, Letter to George from Port Moresby; JHP Murray, Diaries 1904 to 1917.

36 IC Campbell, 'Anthropology and the professionalisation of colonial administration in Papua and New Guinea', Journal of Pacific History, vol. 33, no. 1, June 1998, pp. 69-91.

37 F West, Hubert Murray.

38 IC Campbell, 'Anthropology and the professionalisation of colonial administration'.

39 N Thomas, 'Material culture and colonial power'.

40 JHP Murray, Diaries 1904 to 1917, vol. 2, p. 672.

41 Thorpe Register of the Official Papuan Collection as received at the Australian Museum 1915-1933, MSS National Museum of Australia.

42 JHP Murray, Diaries 1904 to 1917; Thorpe Register, original object labels.

43 F West, Hubert Murray; M Young and J Clark, An Anthropologist in Papua, p. 8.

44 See for example, JHP Murray, 'Native Custom and the Government of Primitive Races with Especial Reference to Papua', Third Pan-Pacific Science Congress, National Research Council of Japan, Tokyo, 1926; JHP Murray, Indirect Rule in Papua: A Paper Read before the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science, Hobart, Edward George Baker, Government Printer, Port Moresby, 1928; JHP Murray, Anthropology and the Government of Subject Races, Edward George Baker, Government Printer, Port Moresby,1930.

45 JHP Murray, Letter to Minister for Home and Territories, December 1907; Government Secretary's Department, Circular Instructions, Edward George Baker, Port Moresby, 1920, NAA A52 354/95 PAP Part 2.

46 Government Secretary's Department, Circular Instructions.

47 FE Williams, papers, Mitchell Library 5/2, Item 9.The British Association for the Advancement of Science's Notes and Queries on Anthropology (first edition 1874, followed by many subsequent editions) was an instructional handbook based on questionnaires written by ethnographers and anthropologists before fieldwork was de rigeur. It was used by travellers and officials (and later as a fieldwork reference by ethnographers themselves) who would collect data and send reports for 'armchair' anthropologists to utilise 'back home'. For a comprehensive explanation of the impact of anthropological questionnaires see J Urry's chapter 'Notes and queries on anthropology and the development of field methods in British anthropology 1870-1920', in Before Social Anthropology: Essays on the History of British Anthropology, Harwood Academic Publishers, Switzerland, 1993, pp. 17-40.

48 IC Campbell, '"A chance to build a new social order well": Anthropology and American colonial government in Micronesia in comparative perspective', Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, vol. 3, no. 3, 2002, http://muse.uq.edu.au.mate.lib.unimelb.edu.au/journals/ journal_of_colonialism_and_colonial_history/toc/cch3.3.html; D Griffiths, 'The career of FE Williams'.

49 Government Secretary's Department, Circular Instructions, p. 1.

50 J Sinclair, Kiap: Australia's Patrol Officers in Papua New Guinea, Pacific Publications, Sydney, 1981; AK Kituai, 'Patrol officers: Beasts of burden of the administration', Yagl-Ambu, vol. 4, no. 4, 1977, pp. 239-247.

51 Thorpe Register.

52 Personnel records of the Territory of Papua 1904-1929, NAA G167/6/1, Item 1 microfilm.

53 Thorpe Register.

54 AR 1913-14, 1914-15.

55 Pitt Rivers Museum catalogue online.

56 Personnel records of the Territory of Papua.

57 Sinclair, Kiap.

58 Annual Report of the Territory of Papua, 1921-22; 1922-23.

59 ibid., p. 122.

60 Annual Report of the Territory of Papua, 1922-23.

61 Annual Report of the Territory of Papua, 1921-22, pp. 122-23.

62 ibid., p. 130.

63 Annual Report of the Territory of Papua, 1922-23.

64 Annual Report of the Territory of Papua, 1900-1940. According to Barry Craig the design on the shield removed by Austen 'represents the southernmost occurrence of this type of artefact in central New Guinea and appears to be a Woröm attempt to copy a Mountain Ok shield'. See B Craig, 'The ashes of their fires: The Hubert Murray collections in the National Museum of Australia', Conference of Museum Anthropologists, vol. 26, 1995, pp. 1833, p. 30. The objects collected by patrol officers are therefore not only important as representations of European collecting, but also as records of contact with Indigenous people and evidence of developments in the material culture of different groups of people within Papua. Aside from the question over whether or not this object was collected ethically, it is a rare and early example of items collected from the Star Mountains, and therefore forms an important piece of the Official Papuan collection.

65 Annual Report of the Territory of Papua, 1922-23, p. 125.

66 ibid., p. 126.

67 Personnel records of the Territory of Papua; Annual Report of the Territory of Papua 1913-14, p. 118.

68 Thorpe Register.

69 FE Williams, Anthropology Report No. 3: The Collection of Curios and the Preservation of Native Culture, Edward George Baker, Government Printer, Port Moresby, 1923.

70 ibid.

71 ibid.

72 M Young and J Clark, An Anthropologist in Papua. The following section on FE Williams is drawn from a presentation I gave at the first conference of the Australian Association for the Advancement of Pacific Studies at the Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, 24-27 January 2006. The presentation is to be published as a chapter in a forthcoming book edited by S Cochrane.

73 Thorpe Register.

74 The ethnographic photos Williams took while Government Anthropologist amount to several thousand and are kept at the National Archives of Australia. They have been the subject of numerous works including the 1999 exhibition at the National Archives of Australia, Eye to Eye: Observations by FE Williams, Anthropologist in Papua 1922-43, and the accompanying book by M Young and J Clark, An Anthropologist in Papua.

75 This photograph is reproduced in Young and Clark, An Anthropologist in Papua, p. 73.

76 These objects are in the Official Papuan collection, NMA 1985.0339.1063 and NMA 1985.0339.1062.

77 See JHP Murray, Letter to Minister of State for External Affairs. Haddon became a very important link between Papua and the development of the discipline of anthropology in Britain. Over the life of Murray's administration, Haddon utilised Murray, his patrol officers and resident magistrates as sources of objects and information for his own work in England, including books on smoking pipes, and on canoes (AC Haddon, 'Smoking and tobacco pipes in New Guinea', Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Series B, 1946; AC Haddon and J Hornell, Canoes of Oceania, vols. I-III, Bernice P Bishop Museum, Honolulu, 1936-1938). Haddon considered Papua a significant fieldwork site for new anthropologists, especially with the support offered by Murray with his own inclination for anthropology. Papua was an ideal launching point for petitioning the Australian Government to establish the discipline of anthropology in tertiary institutions in the Southern Hemisphere (AC Haddon, 'An ethnologist for Papua'). In return, Haddon provided support and advice to those officers who had an interest in anthropology. Haddon, among others, supported FE Williams as a candidate for the position of Assistant and then Government Anthropologist, and continued to correspond with him through both their careers. He also enjoyed receiving reports and anecdotes from resident magistrates, and in the late 1920s he supported Austen in his quest to gain formal qualifications at the University of Sydney (Haddon papers, University of Cambridge Library).

78 JHP Murray, Letter to Etheridge, 19 October 1914, 'Selected documents relating to the Official Papuan Coll'n', folder, Australian Museum Archives (AMA); Etheridge, Minute to staff, 29 May 1915, AMA P:51/15.

79 Thorpe Register.

80 WW Thorpe, memo to Director of the Australian Museum, Australian Museum Archives 3.5.1932. However, in 'The Melanesian Collections of the National Museum of Australia', Craig suggests that around 400 duplicates were kept by the Australian Museum, COMA, no. 25, 1993, p. 17. The discrepancy may be due to multiples being regarded as one item, e.g., a bundle of 10 arrows being equated to '1 arrow duplicate'.

81 Secretary of Australian Museum, Letter to Minister for Home and Territories, 30 September 1927, AMA 754/27.

82 Government Secretary Papua, letter to Director, 21 June 1933, AMA 106/33.

83 D Kaus, 'Pacific collections in the National Museum of Australia, Canberra', unpublished and undated ms.; B Craig, 'The Melanesian collections of the National Museum of Australia', Conference of Museum Anthropologists, 25 September 1993, pp. 1627 (p. 16).

84 Director, Australian Institute of Anatomy, letter to JHP Murray, 22 February 1935, National Museum of Australia Archives green file, folder 2, Papuan collection (Sir Hubert Murray colln).

85 AIA-NFSA transfer Item 7, 'Plan of Ethnographic Gallery Institute of Anatomy November 1984', National Museum of Australia Archives brown box file; Thorpe Register; Melanesian collections catalogue cards, National Museum of Australia.

86 A Kohen-Raimondo, 'National Museum of Australia Melanesian collections', unpublished manuscript, 1999, National Museum of Australia Archives 97/0393.