In the Adelaide summer of 1952 a young Bosnian Muslim and his friends, newly arrived immigrants, pushed open the high gate of the Adelaide mosque, tucked away in the city's run-down south-west corner. As Shefik Talanavic entered the mosque courtyard he was confronted by an extraordinary sight. Sitting and lying on benches, shaded from the strong sunshine by vines and fruit trees, were six or seven ancient, turbaned men. The youngest was 87 years old. Most were in their nineties; the oldest was 117 years old. These were the last of Australia's Muslim cameleers, who had plied the inland routes before the era of motor vehicles began. Several had subscribed money during the late 1880s for the construction of the mosque which now, crumbling and decayed, provided their last refuge.

Gradually Shefik and his friends ministered to the needs of the old cameleers and began restoring the mosque. They stood at the graves of the old men as each passed away. Each cameleer had travelled light during his lifetime, and none had accumulated possessions. Apart from the mosque itself, which stands as the oldest Islamic structure in the southern hemisphere, their gravestones in the Muslim section of West Terrace Cemetery seemed to represent their most tangible legacy. But Shefik soon came to understand that there was another legacy, extraordinary in its scope and significance, but largely unappreciated by a wider public. The cameleers pioneered a network of camel-pads and tracks that later became roads across outback Australia. The homesteads, mines, missions and townships linked by this network depended upon the cameleers for their viability, during the course of five decades or more.

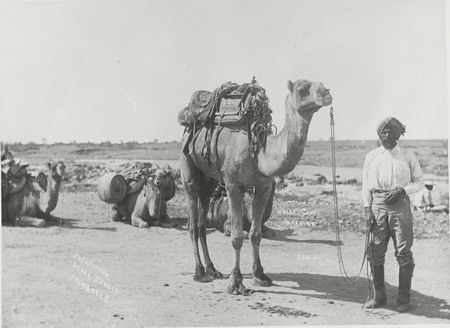

B10486, State Library of South Australia

From the 1860s to the 1920s it is estimated that at least 2000 cameleers reached Australia from their homelands in Afghanistan, Baluchistan and other provinces in the region of north-western India (now Pakistan). 'Afghan' and European entrepreneurs imported more than 20,000 camels, supplementing those being bred in South Australia's north. Descendants of these camels run free today in the arid interior. The great majority of the cameleers returned to their homelands after fulfilling short contracts of two or three years. Of those who remained for longer periods a small proportion formed relationships with Aboriginal or European women. Perhaps no more than 100 of the cameleers had families here, but it is these families that retain living memories of their contribution. The third or fourth generation descendants of these unions are more aware than any Australians of the contribution made by their Muslim grandfathers. In several cases, against the odds it seems, these descendants have preserved fragile and poignant material relics of those past lives.

It is a sobering fact that until preparations for the 'Muslim Cameleers' exhibition at the South Australian Museum began in 2005, no Australian museum had directed its collecting efforts to material culture or documents relating to the cameleers. Birdsville's Working Museum, dedicated to the technology and material culture of the outback, contains no cameleer artefacts, and such objects are barely represented in the Stockman's Hall of Fame at Longreach. Small displays in Coolgardie and at the Broken Hill mosque provide minor exceptions to this neglect.

During 1961 one of Australia's last inland explorers, Michael Terry, recognised the significance of a complete 'Afghan' pack-saddle lying abandoned on a northern South Australian station. His donation to the predecessor of Sydney's Powerhouse Museum resulted in its preservation. The saddle is the only remaining example of hundreds of such saddles, all employing the same simple, efficient design. Its adjustable system of wooden forks and rope ties on a padded base allowed camels to bear loads as heavy as 600 kilograms across hundreds of kilometres.

More than three generations have passed since camel strings made their way along the Birdsville Track, picked up station loading from the Oodnadatta railhead, or delivered bags of ore from the Western Australian goldfields. More than 50 years have passed since the mosques of Coolgardie, Cloncurry, Marree and Broken Hill fell silent, and it is a generation since the last Asian-born camel-drivers were laid to rest in Australian soil. One thinks of the energy and resources directed towards preserving the records and memory of Australia's Chinese pioneers who provided commercial infrastructure for the Victorian goldfields, or the heritage associated with the contribution made by the post-war migrants to the Snowy River Scheme. How is it that the legacy of the cameleers has been so neglected?

photograph by P Jones

It would be easy to suggest the oversight had to do with the cameleers' adherence to Islam in Australia, through their dress, daily prayer, and rigid observance of halal practice. But the cameleers did not come to Australia to proselytise; their construction of earth-walled and iron mosques in outback towns, and more permanent mosques in Adelaide, Perth and later Brisbane, met their own community's need. Despite occasional frustrated references by explorers to their cameleers' zealous adherence to halal butchering practice, their religious observances rarely impinged on their remarkable capacity to deliver goods intact across vast distances of the Australian interior. For these achievements they earned the general respect of their European neighbours. There were exceptions of course. Competition with bullock teamsters in inland New South Wales or Western Australia sometimes led to open conflict. Concern about disease introduced by camels reached flashpoint at times, particularly in Western Australia. Episodes of racism are documented in newspaper columns of the time, particularly as the climate hardened towards Asian immigrants during the 1890s. But reactionary posturing towards the perceived threat of an Asian influx was directed more towards the Chinese than the cameleers. The formulation of the White Australia Policy at the time of Federation affected each community, not only curtailing fresh immigration to Australia, but greatly restricting the capacity of those living here to make visits to their homelands. As the Chinese example shows though, these episodes of unofficial or institutionalised racism were not enough to extinguish an awareness of their contribution to the colonial, pioneer economy.

One reason for the forgetting of Muslim cameleer history may lie with the unbridled enthusiasm throughout the bush for the technology that supplanted camel transport — the motor vehicle. With their shallow roots in outback communities and an uncertain future, perhaps it is not surprising that most elements of the cameleers' material culture, known from documents or old photographs, turned to dust. More recently, greater affluence has seen the rise of bush 'nostalgia', expressed in makeovers of country pubs, the ABC's Australia All Over program, and a country music revival. Not surprisingly, the cameleers and their material culture do not figure in this reshaping of Australia's bush history.

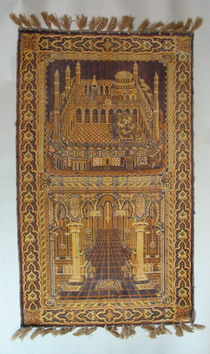

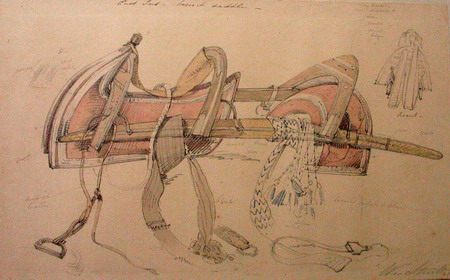

William Strutt album, State Library of New South Wales

The most outstanding early record of cameleer artefacts in Australia consists of the delicate pencil and watercolour sketches drawn by William Strutt in Melbourne during July 1860, before the departure of the Burke and Wills expedition. These drawings provide a benchmark for all the subsequent shifts and permutations in the cameleers' material culture in the Australian context. A decrepit camel saddle frame purchased from a second-hand shop in Melrose during the 1980s, or another purchased at auction in Sydney as recently as 2006, take on new heritage significance when it is realised that they conform exactly to the riding saddles documented by Strutt. On the other hand, the artist's careful renderings of details of woven trappings adorning the Burke and Wills camels have no analogue in surviving artefacts, although Strutt's sketches provide a vital reference in identifying similar trappings worn by leading camels in old photographs. In this way we can chart the gradual abandonment of this decorative tradition in Australia, and link it to practices which continue (albeit in modified form) in the cameleers' homelands today.

photograph by P Jones

Three fine books on the cameleers were written during the 1980s.[1] Those by Rajkowski and Stevens drew upon diverse documents, photographs and interviews with descendants to give insights into the lives of individual cameleers who had worked specific routes, lived in one township or another, and left their mark in official records or in family memories. In fact, these two books, perhaps in contrast to Cigler's more general Afghans in Australia, adopted a specifically biographical approach to the subject, dismantling the stereotype of the nameless 'Afghan camel-driver'. Here the influence of recent Aboriginal historiography, stressing links between contemporary and past generations, is evident. But it seems fair to say that each book also carries an assumption that the heritage of the Muslim cameleers rests mainly in the oral or documentary record. A museum exhibition, of course, starts from an assumption that artefacts and objects provide the 'stuff' of history, and that gaps in the story told by objects can be filled by documents, photographs or oral testimony. It is this assumption that drove my own research on the cameleers. It brought me face-to-face with some remarkable objects and reminded me of these objects' continuing role in the unfolding history of the Muslim cameleers and their descendants.

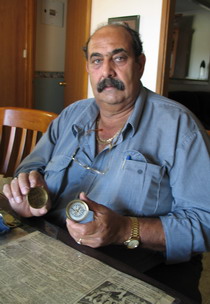

photograph by P Jones

In the half century since his death, the care with which Bejah Dervish's grandchildren have preserved his relics — his cap and turban, pantaloons, rings, the brass compass presented by explorer LA Wells — suggests as much about his descendants' present sense of identity as 'Afghans' as it does about his historical standing. Until recently this sense of identity was contained among family members, or diffused among a wider 'Afghan community' during such events as the annual Alice Springs or Marree Camel Cups, descendant reunions and occasional inaugurations of memorial plaques. These events evoke a warm nostalgia for the cameleer past, with participants dressing in cameleer costume, distributing 'charity' gifts to children as the cameleers once did, or decorating living rooms with camel ornaments. In general, apart from re-enactments involving original clothing, the material culture involved in these gestures consists of substitutes, standing for authentic objects that have slipped from view, just as the last 'Afghans' themselves have vanished. In the meantime though, Afghan refugee immigration to Australia was on the rise by the time Cigler, Rajkowski and Stevens published their histories during the mid-1980s. Australian society was once again being actively regarded from the perspective of the cameleers' homelands.[2] This fact, and the tumult surrounding 11 September 2001, has had unanticipated consequences for the cameleer descendants, and perhaps it has also invested cameleer artefacts with a new set of associations.

photograph by P Jones

Many of the artefacts in the South Australian Museum's 'Muslim Cameleers' exhibition appear to have survived through chance, but their survival can often be traced to particular foresight. The family custodians of Moosha Balooch's wooden travelling trunk well understood its talismanic role as a container of memories. More than any other object in the exhibition, it not only evokes the cameleers' journeys from Asian to Australian deserts, but suggests the cryptic, self-contained lives the original Marree cameleers appeared to lead. They conversed, drank chai and smoked the hookah among themselves, lived on their side of the railway tracks, and observed 'Mohammedanism' until the end. Their grandchildren are left to wonder exactly what they made of Australia and their experience here. Passed down through one of Moosha Balooch's sons, the trunk appears to provide a clue. Another son, Ahmed, pursued the camel business and lived his last years in Marree. His father's cameleering artefacts were stored in a ramshackle old shed; fearing for the safety of these treasures, Ahmed transferred them one by one to the custody of a long-term resident, who lent them for the exhibition. These include a set of camel branding-irons and long implements doubling as punches and sewing needles, used in making camel saddles. No such items are preserved in museums and none are documented in any detail in photographs or written records, yet these are objects that allowed European commerce and industry to thrive in the Australian inland for a period of at least 50 years. Ahmed Moosha seemed well aware of their significance.

photograph by P Jones

Examples of this foresight are also found among European Australians. During the 1940s a young Adelaide woman, Olga Smith, found herself at a fete in St Peters Town Hall in Adelaide, where a small collection of 'Afghan' artefacts was being sold. Some had been gathered by members of the 1939 Madigan Expedition across the Simpson Desert. She bought a handful of objects, including a nose-peg, two turban caps, two leather hobbles and a small embroidered bag containing kohl eyeliner, which cameleers used as protection against the desert sun. Fifty years later, following a house fire in which she lost all her other possessions, Mrs Smith donated these relics, which had been protected in her garden shed.

Descendants of the Hughes family of Nockatunga station in south-western Queensland preserve a small museum of their station artefacts, including three canvas saddle forms stuffed with straw made by descendants of Syed Sideek Baluch. He was one of the last cameleers to carry wool and stores between stations in the vicinity and the rail siding at Cockburn, across the South Australian border. Even more importantly perhaps, the Hughes family has preserved Sideek's letters, in which he gave instructions to the Adelaide office for loading to be delivered to the siding on his arrival there. He specified for it to be carefully distributed in boxes of equal weight, so as not to cause discomfort to his camels. Sideek's literacy in English can be explained by the fact that his 1890s' camel journeys brought him to the border customs post, where bureaucratic encounters necessitated a basic grasp of the language. By the time the camel business flickered and died during the 1920s, sufficient numbers of the cameleers were literate in English for a small, but fascinating archive to emerge.

The leather pouch containing business papers and letters of the Kandahar cameleer, Munjaloon, has been fortuitously preserved by William Bejah, grandson of Bejah Dervish. As well as receipts for stores that Munjaloon delivered to stations along the Strzelecki Track and dockets recording a full loading of wool bales brought south to Farina siding, there are personal letters. None is more poignant than one written during the mid-1920s by the caretaker of the Adelaide mosque, Munjaloon's friend and fellow cameleer Goolam Rasool. The letter ends:You should sell all your property and let us go back to Kandahar. We are getting old, and may die any day, and we ought to go home. If you are not going to do this, put your affairs in order, and make your will. If you die in the jungle tomorrow, Sircar will take all your money. Also, send me L500, as I am poor, and want to go back. God send you good luck and a long life. God give you Heaven. Salaam plenty to all Mohammedan friends, and good luck to everybody. Your friend, Goolam Rasool.

Despite some outstanding examples of foresight, little remains of the heritage of Australia's Muslim cameleers. Many of these fine men 'died in the jungle' with little recognition or understanding from the wider community. Leading their camel strings bearing wool, minerals, water, stores and equipment, they had walked thousands of miles up and down Australia's desert tracks and roads. Goolam Rasool was one of these pioneers, carting wool for Thomas Elder's Beltana Pastoral Company during the 1880s. Never realising his ambition to return to Kandahar, he was among the elderly cameleers who ended their days in straitened circumstances at the Adelaide mosque, dying there in 1941. The lives of Syed Sideek, Goolam Rasool and Australia's other Muslim cameleers will only ever be known from incomplete records. Theirs is a fragmentary history of an era that has almost slipped from view, but which has been critically important in Australia's national story. To enable that story to be told in full, such fragments must be preserved.

2 Indeed, this regard had persisted in some cases; cameleer descendant families in Broken Hill and Port Augusta, for instance, have continued to correspond with distant cousins in today's Pakistan or Afghanistan in the period since the death of the last cameleers.