Old masters

In December 2013, the National Museum of Australia will open the doors on its extensive and significant collection of bark paintings by some of Australia’s greatest painters. Old Masters will be a celebration of the aesthetic genius and craftsmanship of master artists representing diverse schools and traditions from northern Australia.

The Museum’s collection of bark paintings numbers over 2000, and contains some stunning works from a vast region spanning the Kimberley to the Cape. Indeed, many of these works belong to the canon of great Australian art movements and typify an Australian high art that is intimately connected to history, environment and culture.

At the centre of this art form are acts of inspired creation. Individual artists are inspired to create unique works with the things around them: the stories and metaphors that fill their lives and their pasts; the aesthetic forms and practices that constitute the cultural traditions they sit within; the raw materials they use and manipulate; the audience for which they produce; the family that surrounds them, past and present; the country on which they sit. A master artist brings all these things together to create something that speaks into people’s lives.

Some months from the exhibition opening, this paper seeks to explore some of the wider significances of bark painting in a Yolŋu context beyond the apparent tangible record, the physical barks themselves.[1] As the museum conservator is a dutiful custodian of the physical work, so too have the narratives and ideas these paintings bring to life been dutifully carried through the generations of family dynasties. The artist – like the curator who seeks to connect these works with a new audience – plays the role of mediator, infusing stories and traditions with inspiration, effecting new encounters between present generations and the ancestral or traditional text.[2] This movement of creative iteration or conversation with forms and expressions of the past is central to artistic practice in the Yolŋu world of North East Arnhem Land. Here, bark painting is considered only one particular medium of expression within a wider constellation of rom, the Yolŋu concept of life as the correct practice and ongoing re-creation of the ancestral blueprint.[3]

While Old Masters in its iteration as exhibition is focused on one expression of rom, namely miny’tji (design), the paintings on display are essentially inseparable from their complementary expressions of manikay (song), buŋgul (dance), yäku (names) and wäŋa (country).[4] Such expressions are not only formal, liturgical sets of knowledge but poetic vocabularies that together contribute to an understating of human experience overflowing with a rich excess of life and creation. This is known as madayin,an encapsulation of everything sacred, ‘a word that also describes awe-inspiring beauty’.[5]

The creation of bark paintings in resonance with the ancestral text is one expression of life as a following of rom – something greater than mundane substance and a meta-medium that exists in an excess beyond the particulars of musical, graphic, choreographic and linguistic forms of its expression or undertaking. Individually, these particulars of song, design, dance and language carry rom through their illuminations of aspects of human experience that are simultaneously dense, abstract, philosophic, law-containing, tangibly corporeal and creatively engaging. This accumulated body of knowledge, passed down through successive generations, originates beyond definitive human knowledge in the original observations and actions of ancestral progenitors. While innovation is important to ongoing engagement with these repertories of rom, Yolŋu traditions are inherently concerned with questions of orthodoxy, perpetuation and sustenance.

These multiple forms of expressing life as a following of rom engage the creativity of individuals, allowing the ancestral text to be brought into present experience and event. Yet obligations toward the blueprint of rom are not anathema to creativity and innovation. Rather, orthodox approaches to this text demand a seriousness of response in the way forms of the past are brought into new situations: values inherent in orthodox forms are lost where contemporary expressions fail to engage with the dynamic and generative reality that the past underpins and constitutes the present. Indeed, an old master is certainly someone who is capable of engaging with the world of tradition and ancestral essence as it underpins the world of the present.

In the Yolŋu world, the concept of rom is not historical but a present reality – ceremony is ongoing and continues today. A striking example of the way Yolŋu today bring the past into the present is the Australian Art Orchestra’s exciting partnership between songmen from Ngukurr, Arnhem Land, and some of Australia’s foremost contemporary improvising musicians. This project, known as ‘Crossing Roper Bar’, draws upon the skills and creativity of individuals to re-create Yolŋu narratives dramatically through new sounds and contexts of performance – primarily through the responsive improvisations of all the musicians involved.[6] This collaboration can be considered one facet of the continuing Wägilak expression of rom. Benjamin Wilfred, singer, painter and ceremonial leader for the Wägilak clan in Ngukurr, expresses his drive to continue to follow rom by creating with this new technology and contexts of expression:

We do manikay and painting for the country and for leading the new generation: follow what the elders used to do. Manikay means spirit for the country, where he walked, that mokuy [Wägilak ‘ghost’ and founder of their ancestral estate at Ŋilipidji]. We do manikay, buŋgul and painting for the land and for the ground, for the sea, for the trees, animals, no matter what. Everything, no matter where you go.

So me and my brother Daniel, we’re holding strong. Wägilak. That’s how. I got kids and I have to tell them, think about it: hold your manikay strong; hold your culture strong … No matter where I have been touring with the orchestra, I share my culture and talk. No matter where I go.

Every story and every song comes out from the painting and from the heart, and from the country and from the land and from the ground.[7]

photograph by Samuel Curkpatrick

photograph by Samuel Curkpatrick

Much more immediate and vocative than theoretical or analytical, rom concerns law as correct practice – the right way of living, doing and maintaining life as a reflection of patterns established in an ancestral past that simultaneously sustains the present. This right way of living is an imperative to action and responsibility, most evidently manifest in the maintenance of ceremonial practices and the continued performance of ceremony. As is evident in the variety of unique and creative approaches musicians bring to the performance of manikay in Crossing Roper Bar, an orthodox approach to practices handed down through the generations does not preclude innovation or the adoption of new materials or media. The very growth of bark painting as a commercial enterprise and the assertion of Yolŋu cultural legitimacy and local political autonomy within the wider Australian consciousness also attests to this dynamic truth. The Elcho Island Adjustment Movement,[8] Yirrkala Bark Petitions,[9] Saltwater Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country national tour[10] and the phenomenon of Yothu Yindi are just some notable examples of the continual Yolŋu determination to assert ongoing connection with the essential ancestral text through new situations and forms. The paintings on display in Old Masters are also constituted within these traditions.

By continuing to paint and follow rom, Yolŋu are following the luku (footprints) of the waŋarr (ancestral beings):[11] all understanding and human action looking to these footprints as precedent to mirror and genesis to reconnect. Rom demands knowledge and action, and the basic patterns of these important social, political and legal processes are both figuratively and literally contained within ceremonial performance. The creation of a painting is only one articulation of this performance.

Painting as a following of rom

The old masters who constitute this exhibition were on the inside of rom;they held the knowledge of this law of existence as a following, doing and response to established patterns and histories. In considering these artists master painters, we do them an injustice if we limit our appraisal to the identification of aesthetic styles and forms. Old masters Narritjin Maymuru, Mawalan and Mathaman Marika, Birrikidji Gumana, Dawidi Djulwadak or David Malangi could not have been just painters, as the knowledge needed to paint the narratives they capture is acquired only through participation in ceremony: through manikay, buŋgul and the calling of significant yäku; through the energy, sweat and exhilaration of ceremony; through close proximity to other bodies and contiguity with the very wäŋa that is sung. In the Yolŋu tongue, these men strove to become liya-ŋärra’mirr(i) (learned and wise elders).[12] They painted not simply for acclaim or financial gain. They did not paint sequences of past events or narratives full of arcane references detached from present reality; they did not just create designs of visual and aesthetic appeal and coherence. These men painted songs and they danced those paintings. They walked on the country and through painting they sustained that country as an ongoing expression and reverberation of ancestral reality.

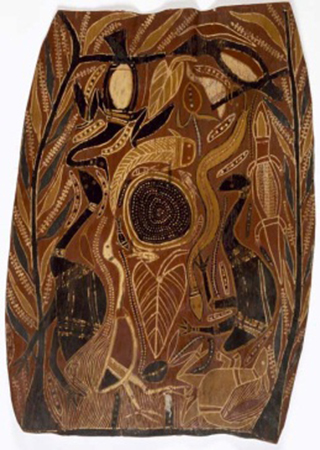

![The Night Bird Karawak [Guwak] and the Opossum Marnungo [Marrŋu] depicting a central text of the Manggalili clan, 1948, attributed to Narritjin or Nanyin Maymuru](https://recollections.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/image/0005/378509/Curkpatrick_Old_Masters_Image_3_500h.jpg)

In this narrative, the geometric designs represent specific places related to the country of Djarrakpi.

National Museum of Australia

Considering the brilliant and aesthetically captivating ‘artworks’ at the centre of the National Museum of Australia’s bark painting collection, it is easy to forget the songs, dances, language and country that deepen and validate the particular designs as components of a greater, richer narrative.[13] In one sense, these bark paintings are inscriptions, perhaps musical scores, demanding to be sung and lived into being. These texts exude a multitude of significations, and the great artists who created them spoke into this hermeneutic tradition with experience, creativity, skill and celebration. In pointing to the ancestral underpinning of existence, the present resonates with this blueprint established long ago. In the act of creating, these old masters draw attention to the very important and reality-changing observation that the world too is created and bursts with an abundance of life and sentience.

National Museum of Australia

Liturgical texts of tradition call forth a response as something that speaks into human lives. Painting is one form of response to life as a following of rom that in turn generates responses into the future. The characters and stories in these paintings refuse to lie down and become mere objects stuck in some repository of musty heritage; they refuse to be inanimate references to culture; they refuse to become culture in its derivative sense – objects that point to themselves. Rather they are alive and they are burning with imagination, engaging in their aesthetic brilliance. As German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer makes clear:

When a work of art truly takes hold of us, it is not an object that stands opposite us which we look at in hope of seeing through it to an intended conceptual meaning. Just the reverse. The work is an Ereignis – an event that ‘appropriates us’ into itself.[14]

An old master is one who commands a particular form of expressing rom, here bark painting, and creates this vibrant Ereignis. Through these works the creativity and technique of the individual come to the fore, offering a culturally legitimate yet engaging iteration of the ancestral text that speaks into new contexts and unique lives: painting as rom is the performance of ancestral constitution in the present.The Old Masters exhibition seeks to celebrate the creativity, inspiration, skill and innovation of these individuals that are central to the essential movement off the bark and into life.

Old Masters will open at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, in early December 2013.

Endnotes

1 This article limits its comments specifically to pervasive Yolηu explanations of rom. Note on pronunciation: ŋ, similar to ‘ng’ as in song; ä, long ‘a’ as in far

2 Samuel Curkpatrick, ‘Conversing tradition: Wägilak manikay ‘song’ and the Australian Art Orchestra’s ‘Crossing Roper Bar’ (PhD thesis), Australian National University, 2013.

3 See Aaron Corn, ‘Ancestral, corporeal, corporate: Traditional Yolŋu understandings of the body explored’, Borderlands, vol. 7, no. 2, 2008, 1–17; Fiona Magowan, ‘“It is God who speaks in the thunder ...”: Mediating ontologies of faith and fear in Aboriginal Christianity’, Journal of Religious History, vol. 27, no. 3, 2003, 293–310.

4 Aaron Corn, ‘When the waters will be one: Hereditary performance traditions and the Yolηu re‐invention of Post‐Barunga intercultural ciscourses, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 28, no. 84, 2009, 1–13 (p. 5).

5 ibid., p. 26.

6 For more information on the Crossing Roper Bar collaboration, performances and recordings, see www.aao.com.au.

7 Samuel Curkpatrick, Benjamin Wilfred, Daniel (Desmond) Wilfred & Justin Nunngarrgalug, ‘Digital audio technologies and aural organicism in the Australian Art Orchestra’s Crossing Roper Bar’, unpublished paper presented at the Information Technology and Indigenous Communities conference, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 13–15 July 2010, Canberra, Australia.

8 RM Berndt, An Adjustment Movement in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory of Australia, facsimile edition of Oceania Monograph No. 54, [1954] 1962, University of Sydney, Sydney.

9 Howard Morphy, ‘Art and politics: The Bark Petition and the Barunga Statement’, in Sylvia Kleinert & Margo Neale (eds), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, p. 100.

10 Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Saltwater: Yirkala Paintings of the Sea Country, Jenny Isaacs Publishing, Sydney, 1999.

11 Corn, ‘Ancestral, corporeal, corporate’ (p. 3).

12 Ian Keen, Knowledge and Secrecy in an Aboriginal Religion: Yolngu of North-East Arnhem Land, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1994, p. 92.

13 For more on Maymuru’s [attributed] The Night Bird, see Howard Morphy, ‘Narritjin Maymuru’, in Mary Eagle, Howard Morphy & Ian Chubb, Three Creative Fellows (exhibition catalogue), The Australian National University, Canberra, 2007, p. 34.

14 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, Continuum, London, 2006, p. 71.