Captivating and curious

An exhibition case study

by Guy Hansen

Captivating and Curious opened at the National Museum of Australia on 14 December 2005. This exhibition explored the history of the National Historical Collection (NHC), the Museum's main collection, from its origins in the Institute of Anatomy through to the present day. One of the most successful temporary exhibitions ever organised by the Museum, Captivating and Curious demonstrated the public's strong interest in the idea of the National Museum as a repository of the nation's treasures. Initially intended as a modest survey of the Museum's collecting activity over time, the exhibition quickly evolved into an important statement of the worth and value of the NHC.

In this article, I will argue that Captivating and Curious was a landmark exhibition in the development in the history of the National Museum. For the first time since its opening, the Museum turned the spotlight onto its own collections and their history. The exhibition set out to historicise the NHC by explaining the motivations behind the acquisition of major collections. Rather than presenting the NHC as a monolithic collection of national treasures, Captivating and Curious attempted to provide a more complex story in which the changing paradigms underlying the Museum's collecting were exposed. Approaches such as ethnography, comparative anatomy, social history, multiculturalism and environmental history all contributed to building the collection. Examining the various stages of the NHC's development provides an archaeology of twentieth-century curatorial practice.

Captivating and Curious was also different to many of the Museum's previous exhibitions in that it was strongly 'object'-centred. Instead of using objects to explore a historical theme or idea, the objects themselves were the starting point for a discussion of how the NHC was formed. By celebrating key objects in the Museum's collections, the exhibition asserted the importance of collecting as a key Museum activity. Most importantly, Captivating and Curious provided a clear statement that, despite the oft-repeated criticism that the Museum lacks objects capable of exciting the visiting public, the NHC is a nationally significant collection with the potential to both educate and attract large audiences.

Reviewing the development of Captivating and Curious highlights some important issues for museums. How should an institution present the history of its collections? What are the political consequences of failing to promote and explain the significance of a collection? What are the advantages of object-centred displays for exploring Australian history? What are the limits of object-centred interpretation? Do exhibitions such Captivating and Curious, despite the stated objective to provide a more complex story, simply repeat the cliché of presenting museums as treasure houses? In this paper I provide some initial reflections on these questions while also providing an account of the curatorial and design intent of the exhibition as originally conceived.

My role was that of the lead curator for the exhibition. As such, this article is intended to be a reflective piece about my own professional practice as a curator. While there are inherent dangers in judging one's own work, I would argue that this process of self-evaluation is essential to achieving a better understanding of curatorial practice. Unfortunately their ephemeral nature means that many exhibitions leave little trace after they have been de-installed. If not documented when in place, information about what objects were used and how they were interpreted can be lost. The transient nature of exhibitions highlights the need for curators to preserve a record of their exhibitions. Without such a record, it is difficult to conduct an informed discussion about changes in exhibition practice. There is a danger that new curators will be condemned to 'reinvent the wheel' as they encounter problems that have been solved many times before by their predecessors.

Exhibition background

The proposal for an exhibition on the history of the NHC emerged at a pivotal moment in the Museum's history. In the wake of the controversy surrounding the opening of the Museum in 2001, the Australian Government commissioned a review of the Museum and its programs.[1] The review, chaired by sociologist John Carroll and completed in 2003, was critical of the Museum in a number of areas and described the NHC as 'immature'. It recommended the Museum initiate a major acquisitions program with the objective of building a set of 'national treasures' that would eventually become a 'lighthouse beam, illuminating Australian culture as powerfully as visitors expect'.[2]

While the Carroll report was not explicitly critical of the NHC, there was a definite sense that the report's 'faint praise' was damaging to the National Museum's reputation. It was clear that Carroll, the report's major author, believed that the Museum lacked the numinous objects required to explore Australian history. He was not the only one — prior to the Carroll report some media commentators vociferously expressed the opinion the Museum's collection was sub-standard. For example in 2001, soon after the opening of the Museum, newspaper columnist Miranda Devine published a scathing commentary describing the Museum as 'all upside down Hills Hoists and tongue-in-cheek Victa lawn mowers'.[3]

Leveraging off the perception that the National Museum of Australia needed to significantly improve the quality of its collection, director Craddock Morton successfully argued for the establishment of an acquisitions fund for the Museum. For the first time in the Museum's history, there was a dedicated budget for the purchase of historical material. This enabled the acquisition of a number of major items, including an early prototype model of the FX Holden and a water bottle believed to be recovered from the Burke and Wills expedition of 1860–61. Prior to the creation of the acquisitions fund, purchases of high value collections were rare and only made possible by reallocating priorities within the Museum's operating budget or by special arrangement with the government of the day.

By 2005 Morton felt that the time had come to celebrate the NHC and asked staff to prepare a proposal for a major exhibition on the history of the collection. The trigger for this request was the need to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the National Museum of Australia Act (1980). There was a happy coincidence between this anniversary and the desire to make a strong public statement that the NHC was an important public collection. Also figuring strongly in the background was the success of the National Library of Australia's exhibitions, Treasures from the World's Great Libraries (2001) and National Treasures (2005), both of which had demonstrated the popularity of displays exploring the history of collections. The popularity of the National Library's exhibitions boosted the confidence of the Museum in its own venture to present the highlights of its own collection in a major exhibition. The exhibition was produced in a six-month period and opened in December 2005.

Developing the exhibition

All exhibitions are collaborative exercises.[4] As lead curator, I resisted the temptation to select my own personal favourites from the collection and instead sought input from staff across the Museum. This provided a shortlist of collection items from which to work. My role was to 'stress-test' this list to ensure the objects were representative of the major periods of collecting in the history of the institution, and to develop a story line that would weave these objects into a narrative explaining the history of the NHC.

Given that the National Museum of Australia only came into existence as a legislative entity in 1980, many would assume that it has a small and relatively recent collection. This, however, is not the case. The NHC consists of over 200,000 items collected by the Commonwealth Government over the past century. Modest compared to some of the state institutions, the NHC nevertheless represents one of the major holdings of historical material in Australia. Reviewing the history of the collection demonstrates that, while the collecting had at times been ad hoc and opportunist, the combined result is a significant collection with the potential to tell many stories about Australian history and culture. The 2005 exhibition provided an opportunity to uncover the motivations behind the creation of collections, and demonstrate how collection material can be used as historical evidence. I strongly believed that providing a sense of this history was essential in order for the exhibition to be more than a simple presentation of national treasures. The challenge for Captivating and Curious was how to convey the story of the NHC to a broader audience.

First impressions

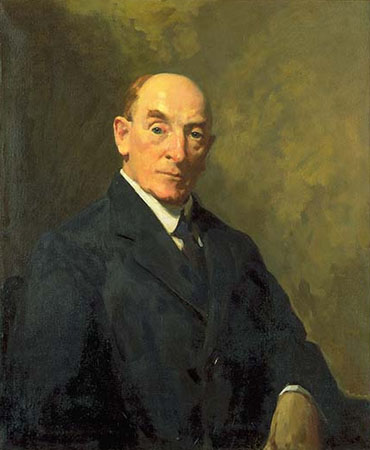

The MacKenzie collection

A man of considerable wealth and extensive political connections, MacKenzie devoted much of his professional life to building an extensive collection of Australian animal specimens. He viewed Australian marsupials and monotremes as important, not just as examples of endangered species, but also for their potential to provide insights into the treatment of disease. The complexities of the human body, he argued, could 'only be revealed by a study of types of animals in which these can be demonstrated in their simpler form'.[6] Australian animals were unique, providing a rich field of comparative examples that could be used to better understand human anatomy.[7]

MacKenzie, convinced of the national significance of his work, offered his collection of specimens to the Australian Government. The collection consisted of approximately 2000 items, including a variety of wet and mounted specimens and anatomical drawings completed by artist Victor Cobb. The government responded to MacKenzie's generous offer by creating the National Museum of Australian Zoology in 1924. MacKenzie was appointed the museum's first director and, in 1929, received a knighthood in recognition of his contribution to medical research. In 1931, the Museum of Australian Zoology changed its name to the Australian Institute of Anatomy to coincide with the opening of its Canberra home.[8] The new title reflected MacKenzie's goal of creating a major research facility that focused on comparative anatomy. The building that housed the institute was one of the first major public buildings in Canberra and is today the home of the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA).

The National Ethnographic collection

In addition to storing and exhibiting MacKenzie's anatomical specimens, the Australian Institute of Anatomy also cared for the National Ethnographic collection. This was a diverse collection of a number of sub-collections comprising more than 20,000 items, initially acquired by some of Australia's earliest collectors of Aboriginal and Pacific material. This material later provided the basis for the National Museum's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander collections, today considered one the best collections of Australian Indigenous material in the world.

At first glance, MacKenzie's acquisition of these collections sits awkwardly with his interest in comparative anatomy. For MacKenzie, however, there was a close link between the fate of Australian fauna and Aboriginal people. MacKenzie saw a parallel between the impact of settlement on wildlife and declining numbers of Indigenous people. As he described it, 'Thanks to poison and the gun they are rapidly following the fate of the Tasmanian nation which was completely destroyed in a period of about 40 years, constituting the most colossal crime our earth has known'.[9] Tasmania had come to symbolise a microcosm of what could happen on the mainland. While perhaps distasteful to modern sensibilities, MacKenzie's conflation of Aboriginal people with Australian fauna was a major motivating factor in his desire to collect Indigenous material.

A selection of material from the National Ethnographic collection was included in Captivating and Curious. Again, the interpretative strategy was to unveil the motivations of the original collectors, and turn the spotlight on some significant early collections:

- Edmund Milne collection: Milne, an assistant commissioner for the New South Wales Railways, collected Indigenous material from the 1870s through to the 1910s. Milne's work on the railways took him around the state, enabling him to meet Aboriginal people and build a collection of artefacts. He displayed his collection in his home, arranging items by their type and size. He also gave public lectures on the 'Australian stone age', emphasising the importance and value of Aboriginal culture. Anticipating Canberra's future as the home of national institutions, he bequeathed his collection to 'the first Federal Museum opened in the Federal Capital'.[10]

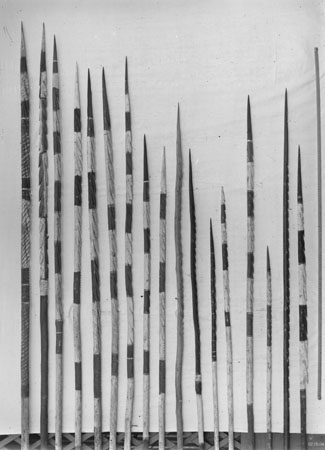

- Herbert Basedow collection: Basedow was one of Australia's first trained anthropologists. Between 1903 and 1928, Basedow, who was also a medical doctor and geologist, took part in many expeditions to central and northern Australia. While these expeditions were primarily organised to conduct surveys of the health of Aboriginal communities and to survey potential mineral resources, Basedow always took the opportunity to collect objects, photograph and record field observations of Aboriginal culture.[11] Objects displayed from the Basedow collection included 17 Tiwi spears he had collected from Bathurst Island in about 1911. The spears were displayed in an arrangement inspired by a photographic plate in Basedow's article, 'Notes on the Natives of Bathurst Island, North Australia', published in 1913.[12]

photograph probably by Herbert Basedow National Museum of Australia

- Material transferred from the University of Sydney: These fieldwork collections were made by anthropologists working in the late 1920s and 1930s. Part of their significance stems from the fact that Sydney University was the first Australian university to establish an anthropology department. AR Radcliffe-Brown and AP Elkin were leading figures in the department, encouraging students to undertake fieldwork across Australia, including Cape York, Arnhem Land, central Australia, the Kimberley and Bathurst Island. Much of this fieldwork was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation of America. Artefacts collected on these field trips were included in the exhibition.

- Official Papuan collection: In addition to Aboriginal material, Captivating and Curious also featured examples of Pacific material culture, collected by officials during the period of Australia's administration of Papua in the early twentieth century. Originally intended for a Papuan museum, the collections were sent for safekeeping to the Australian Museum in Sydney. They were then sent to the Australian Institute of Anatomy in 1934. Objects displayed in the exhibition included an eraho mask from the Elema people collected by Francis Edgar Williams, the government anthropologist in Papua from 1922 to 1943.[13]

- American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land collection: The Institute of Anatomy continued acquiring ethnographic material after the retirement of MacKenzie in 1937.[14] A good example of a collection acquired in this way was the material collected under the auspices of the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land in 1948. This was a multidisciplinary expedition that set out to explore the Aboriginal culture and natural history of Arnhem Land. One of the bark paintings from this expedition was featured in Captivating and Curious. A bark was selected for display because the expedition played an important role in encouraging people to view these works as art, rather than simply as ethnographic objects.[15]

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS) collection: The Institute of Anatomy also stored collections on behalf of the). AIAS was created in 1961 with the aim of promoting research into Indigenous culture. It funded fieldwork around Australia and purchased significant collections of Indigenous material. One of its major areas of material culture collecting was bark paintings, resulting in one of the largest collections of barks in the world. Collections acquired by AIAS were mainly sourced from northern Australia. Many of these collections were eventually transferred to the NMA. Among the AIAS material on display in Captivating and Curious was a selection of mortuary posts collected by Helen Groger-Wurm in the late 1960s, and items collected by other AIAS researchers, Howard Morphy, Brian Hayden and Janet Mathews.

Big things

Gift of the New South Wales Government, part of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Cames collection

National Museum of Australia

Ian Metherall collection, National Museum of Australia

Peter and Wyn Herry collection, National Museum of Australia

Royal Australian Historical Society collection, National Museum of Australia

Collecting from the environment

A selection of objects documenting the hardships of farm life, ancestral links with the land, the love of the outdoors and scientific interest in Australian flora and fauna were included in the exhibition. This included a pyramid of wheat and grain specimens assembled by a former judge of wheat at agricultural shows from the winning strains of 1886–1926.[23] The pyramid incorporates strains that are no longer grown and represents almost 50 years of crop development.

Department of Home Affairs collection, National Museum of Australia

Another exhibit that explored the history of European settlement was a pearl necklace and matching brooches from about 1826.[24] These were among the few possessions kept by Janet Templeton after declaring bankruptcy during the agricultural depression of the 1840s. Templeton had emigrated from Glasgow with her children and relatives, the Furlongs, in 1831. They had brought with them a flock of Saxon sheep, an influential breed in the development of Australia's fine merino wool industry. The sheep were purchased with the proceeds of the estate of Templeton's late husband, a Scottish financier and banker.

The growing interest in the bush as a place of leisure was reflected in the display of a bushwalking pram and leather dog boots from the 1930s.[25] These belonged to Myles Dunphy, a pioneering conservationist. Myles adapted the pram so that his son Milo could join the family on bushwalks. Myles enthusiasm for the bush is further demonstrated by the intriguing leather boots custom made to protect the paws of the family dog, Dextre. Also from the 1930s, and demonstrating a growing interest in Australia's floral emblems, was a wildflower quilt made by Nettie McOlive.[26] McOlive, who grew up on a dairy farm in Eurelia, South Australia, had been highly commended for this quilt in a competition run by the Adelaide Chronicle in 1933.

Fame and infamy

Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton collection, National Museum of Australia

Milestone markers

Surrounding this large central show of personal items was a selection of material reflecting major events in Australian history. The curatorial intent in this area was to demonstrate how the Museum holds material reminders of Australia's past. This includes items associated with landmark events as well as popular culture and social history material. Most of the items displayed were collected after the Museum was established in 1980. Objects included bunting that celebrated the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York in 1901; a 1920s waterside workers trade union banner; a Latvian folk costume brought to Australia after the Second World War; a 1950s' Australian migration poster; a TCN television camera used in the first broadcast of commercial television in 1956; a control panel from the Orroral Valley Tracking Station near Canberra, used in the 1960s as part of the American National Aeronautics and Space Administration's worldwide STADAN network; a Depression-era child's dress made out of old curtains and painted with slogans such as 'Have you got a job for daddy?'; a protest placard featuring the memorable date 11–11–75 (marking the dismissal of the Whitlam government); and a sign from the original Aboriginal tent embassy that was established in front of Parliament House in January 1972.[29] No attempt was made to link these objects into a causal narrative. They did not make an argument about the flow of Australian history but rather served to provide a physical sense of that history. For the majority of visitors these objects had their own resonance and acted as triggers for memories and to stimulate discussion about Australia's past.

The review of historical moments was brought to a close with examples of contemporary collecting. An Australian flag recovered from the ruins of the World Trade Center in New York following the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001 provided a reminder of the lead-up to the war in Afghanistan and Iraq.[30] The effect of terrorism on Australia was illustrated by material salvaged from the Australian Embassy in Jakarta after being damaged by a car bomb on the morning of 9 September 2004. This display included the broken embassy coat of arms, the shattered ambassador's window and the carpark clock, frozen at the time of the explosion.[31]

World Trade Center collection, National Museum of Australia

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material

display photograph by Dragi Markovic, National Museum of Australia

The 'Lab'

Evaluating Captivating and Curious

Conclusion

Viewed from a distance, a museum's collections can appear monolithic, as having always existed in a coherent mass. Reviewing the history of the NHC shows a more complicated picture. The collection is not the result of a single hand, but rather reflects many people's efforts in preserving material for future generations of Australians. It becomes clear that a number of different collecting paradigms have driven the development of the NHC. Comparative anatomy, ethnography, environmental history and social history have all contributed to the shape of the Museum collections. Government policies, such as the assertive cultural nationalism of the 1970s, the multiculturalism of the 1980s, and the culture wars of the 1990s, have also helped define the limits and possibilities of the collections. Understanding this history and communicating its significance is an essential part of preserving the NHC.

While Captivating and Curious was undoubtedly successful, the need to promote the significance of the NHC remains a pressing issue for the NMA. In 2009 former prime minister Paul Keating argued in an article in the Weekend Australian that the National Museum of Australia lacks the necessary collection base to be a truly great national museum. In his words, national museums must 'have large and varied collections of the many ordinary and, sometimes, great things that tell the story of how a society developed and how life was lived through particular periods'. For Keating, the construction of the Museum rushed ahead without the necessary collections groundwork to underpin the building. Rather than spend money on construction of an exhibition venue, Keating argued that the development of the collections should have taken priority: 'The important thing, I thought, at this stage was the dragnet; the harvest'. For him, the Howard Government's decision to proceed with the Museum resulted in a 'national lemon'.[36]

Craddock Morton forensically rejected Keating's rebuke of the Museum, pointing out that it was a pity the former prime minister had not, during his tenure, matched his belief in collection building with additional funds. Morton stated: 'As far as I am aware the National Museum of Australia did not have an acquisition fund until it was provided with one by the Howard government in 2004. Prior to this its capacity to acquire objects was almost non-existent, unless they came from donations or the transfer of already existing collections'.[37]

While Keating's remarks, and Morton's rebuttal, post-date the development of Captivating and Curious, their exchange demonstrates the importance of how a museum's collection is perceived. The Museum's current director, Andrew Sayers, has reiterated the importance of this task. In a recent address to the National Press Club, Sayers argued that the Museum 'is still at the beginning of the long range task of bringing together a collection of objects that carry some national symbolism'.[38] For the Museum to attract the necessary support from government, it is essential that it makes the case that its collection is a national treasure. One of the main objectives of Captivating and Curious was to demonstrate that the NHC is a unique and important national asset and that the Museum has a vital role to play as custodian of this collection. In 2011 the challenge remains for the Museum to demonstrate to government and the people of Australia that its collections are an invaluable asset for exploring Australian history and culture.

1 For an account of the political controversies surrounding the Museum at this time see Guy Hansen, 'White hot history', Public History, vol. 11, 2004, 39–51; Guy Hansen, 'Telling the Australian story at the National Museum of Australia', History Australia, vol. 2, no.3, December 2005, 90.1–90.9

2 John Carroll (chairman), Review of the National Museum of Australia — Its Exhibitions and Programs: A Report to the Council of the National Museum of Australia (the Carroll report), Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2003, pp. 52–3.

3 Miranda Devine, 'A nation trivialised', Daily Telegraph, 12 March 2001, p. 3.

4 The curatorial team for Captivating and Curious was Guy Hansen (lead curator), Johanna Parker, Cinnamon van Reyk and Almaz Berhe. The exhibition was designed by Thylacine, an ACT-based design firm.

5 Professor Colin MacKenzie, 'The medical importance of the native animals of Australia', paper circulated for the information of Honourable Members by the Honourable the Chief Secretary, MacKenzie papers, National Museum of Australia, 1924, p. 1.

6 MacKenzie's study of koalas reflects this argument. He observed that koalas possessed a hyperextension in their arms, allowing them to grasp gum leaves above their heads. Using detailed dissections of koala shoulders, he was able to design a shoulder splint as a treatment for sufferers of infantile paralysis. The splint held the arm out from the side of the chest helping to re-educate damaged muscles. MacKenzie was later able to adapt this technique when working as a surgeon at the Military Orthopaedic Hospital in Shepherd's Bush, London, during the First World War. Here, the splint technique was used to treat soldiers with wounds to their upper limbs: ibid., p. 1.

7 Monica MacCallum, 'MacKenzie, Sir William Colin (1877–1938)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 10, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 1986, pp. 306–8.

8 ibid., p. 307.

9 Professor Colin MacKenzie, 'The importance of zoology to medical science', Presidential address, Australian Institute of Anatomy, 1928.

10 David Kaus, 'Collecting by railway: The Milne collection of ethnology', Masters thesis, University of Canberra, Canberra, 1998, p. 63.

11 David Kaus, A Different Time: The Exhibition Photographs of Herbert Basedow 1903–1928, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2008.

12 Herbert Basedow, Notes on the Natives of Bathurst Island, North Australia, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1913, Photographic Plate No. 9.

13 Sylvia Schaffarczyk, 'Australia's Official Papuan collection: Sir Hubert Murray and the how and why of a colonial collection', reCollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 1, no. 1, March 2006, pp. 41–58, http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_1_no_1/papers/the_papuan_collection. 14 This was partly because of the historical precedent MacKenzie established, but also for the pragmatic reason that there was no other Commonwealth institution in which to store this material. The Institute of Anatomy had become, almost by default, home to these collections.

15 National Museum of Australia collection file 9315448.

16 Mathew Trinca, 'The Investigator's anchor', in Captivating and Curious: Celebrating the Collection of the National Museum of Australia, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2005, p. 22.

17 Ian Metherall collection (NMA 2004.0033.0001).

18 Daniel Oakman, 'Australia's own car', in Captivating and Curious, p. 72.

19 Peter and Wyn Herry collection (NMA 2002.0016.0002).

20 Royal Australian Historical Society collection (NMA 1986.0038.0001).

21 Denis Shephard, 'The gentleman's coach', in Captivating and Curious, p. 26.

22 Ian Abdullah collection (NMA 1990.59.03).

23 Department of Home Affairs collection (NMA 1986.0037.0116).

24 Diana Baxter collection (NMA 1998.0020.0002).

25 Myles Dunphy collection (NMA 1987.0045).

26 Nettie McOlive collection (NMA 2000.0009.0002).

27 Carroll report, p. 13.

28 Governor Macquarie's dirk and scabbard (NMA 1993.0005.0002); Azaria Chamberlain's black dress (NMA IR 1577.0008.001); RG Menzies film camera (NMA 1993.0026.0001).

29 Bunting celebrating the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York in 1901 (NMA 1999.0017.0124); a 1920s waterside workers trade union banner (NMA 1986.0040.0001); a Latvian folk costume (NMA 1986.0040.0001); a 1950s Australian migration poster (NMA 2002.0047.0010); a TCN television camera (NMA 1986.0088.0995.001); a control panel from the Orroral Valley Tracking Station (NMA 1986.00086); a Depression-era child's dress (NMA 1986.0002.0001 ); protest placard featuring the iconic date 11–11–75 (NMA 2003.0005.0001); sign from the Aboriginal tent embassy (NMA 1987.0090.0001).

30 World Trade Center flag (NMA 2008.0011.0001).

31 The bomb exploded four metres in front of the embassy gates, propelling shrapnel far and wide. The windows to the front offices of the embassy were blown in, but the structure withstood the force of the blast. Ten Indonesians died. Department of Foreign Affairs collection (NMA 2005.0060).

32Lightning Man, by Jimmy Nakkurridjdjilmi Nganjmira (NMA 1991.24.3788); Redback Graphix print (NMA 2002.0008.0002).

33 Oscar's sketchbook (NMA IR 2269.0001); Transcription of the Jerilderie Letter (NMA 2001.0015.0004.006).

34Captivating and Curious, Results of 50 exit interviews, 2006, National Museum of Australia Internal report.

35 Sixty-eight per cent stated that they knew nothing about the collection with a further 24 per cent saying they had some knowledge.

36 Paul Keating, 'Lame excuse for a national lemon', in 'Review', Weekend Australian, 25–26 April 2009, p. 36.

37 '2020 vision: The National Museum of Australia over the next decade', speech by Craddock Morton, director, National Museum of Australia, to the Friends of the National Museum of Australia, 24 June 2009.

38 'In the national interest: The National Museum of Australia', Address by Andrew Sayers AM, director, National Museum of Australia, National Press Club, Canberra, 16 March 2011, viewed at http://nma.gov.au/events/national_press_club_andrew_sayers/.