‘Memories made real’: Material culture and Arthur Ransome

Finding and explaining congruence between life and art is a staple of literary biography and analysis. This article seeks to explore the material culture of an author’s life and work; an approach that has attracted relatively little interest, despite the massive industry that literary biography has become. It examines the material culture of Arthur Ransome (1884–1967), who is best known as the author of the Swallows and Amazons children’s novels that are set largely in the English Lake District and published from 1930 to 1947. Ransome also worked as a political journalist, and his engagement with the Russian Revolution brought him to the frontier between reporting on events and becoming a part of them.

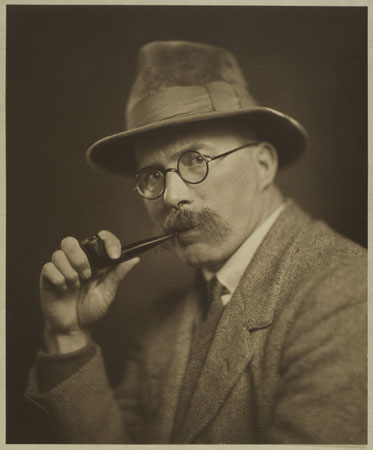

courtesy Arthur Ransome Literary Estate reproduced with the permission of Special Collections, Leeds University Library

Objects figured in Ransome’s earliest memories, including his recollection of seeing, aged two, ‘gaily painted schooners’ in Belfast harbour, a wagonette in an Irish village, snowdrops under trees, and (at three) carrying a blue mug to a tea in Yorkshire celebrating Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee.[1] Significant objects form a minor theme in Ransome’s fiction. In his 1943 children’s novel The Picts and the Martyrs, the 11th volume in the Swallows and Amazons series, for example, we read of the bespectacled swot Dick Callum’s fear that, while he and his sister Dorothea are on holiday in the Lake District, his mother would clean out the ‘treasures’ he keeps in a ‘museum’ in his bedroom. Dick’s fears prove to be groundless: his mother writes to reassure him ‘I am not touching Dick’s Museum’.[2] This aspect of Dick Callum’s character is based, we learn from Ransome’s published autobiography, on Ransome’s interests as a boy in Leeds when, inspired by a visit to the city’s museum, he created his own museum in a washstand, displaying boyish treasures and curios from his Australian relatives. Objects were a part of the creative amalgam of Ransome’s fiction – a product of his personality and upbringing – and the analysis and exegesis of Ransome’s life and art, and of the relations between the two, suggest that it would be productive to further explore the objects that Ransome valued.[3] This article is not intended to offer a definitive canvass of Ransome’s material culture, but it suggests some questions, issues, approaches, provisional conclusions and urges further work in this area.

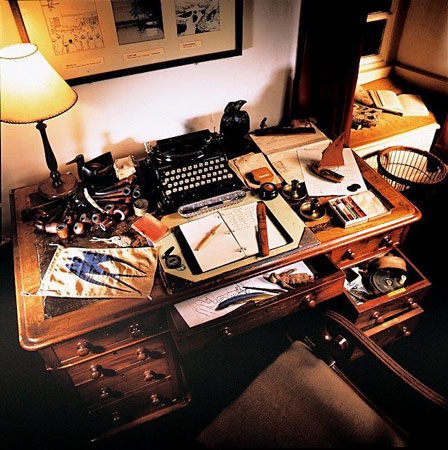

In time Ransome himself became part of a museum display. In its recently refurbished ‘Arthur Ransome Room’, the Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry in Kendal, Cumbria, displays a desk that once belonged to him. Under a protective perspex cover are arranged a selection of the tools, keepsakes and curios that Ransome kept on his working table: a typewriter (of course), typewriter ribbons, sealing wax and pencils; but also a stone, a compass, a couple of pennies and a battered plaster cat. In a nearby display case are what seems to be Ransome’s entire published works and further items – notably a pair of red leather slippers of what news reports would today obliquely refer to as being of a ‘Middle Eastern appearance’. These are what Ransome authority Christina Hardyment, in her ‘companion guide’ to Ransome’s work, calls ‘memories made real’.[4]

The meaning of Ransome's objects

How significant are these objects? What can they tell us about the man and his work? This is no idle or artificial question. Things – possessions, keepsakes or souvenirs – plainly mattered to Ransome, and he acknowledged his tendency to ‘the magpie-ishness of collecting’.[5] His work, fictional, autobiographical and journalistic, his correspondence, and the recollections and insights of others all support the insight that what museologists grandly call ‘material culture’ – the ‘stuff’ he collected or created – has an importance in explaining his personality, literary life and creative spirit. This article asks – for the first time – what might be revealed from a study of his ‘toys’ (as his second wife Evgenia, known as Genia, dismissively called them).[6]

As an aspiring writer with self-consciously literary and Bohemian proclivities in Edwardian London, Ransome made the acquisition and possession of books second only to the acquisition and fostering of literary friendships. He would buy books not only – not even – to read, but would regard and treat them above all as objects of veneration: they constitute a distinct aspect of his material culture. Hugh Brogan records that Ransome bought a copy of Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy not to read it but, merely, to look at it and enjoy the sense of possessing it. There is a curious echo of this behaviour in the writing of Swallows and Amazons, the first book in the series. Ransome recalled how, as the number of pages of typescript grew, he would bring them into the house from his workroom, placing them beside his bed so that, if he awoke in the night, he could reach out to touch the pile: ‘it was as if that book were the first that I had ever written’ – this after more than 20 years as a jobbing writer.[7] Ransome was a man for whom books were not just tools or convenient repositories of knowledge, or even beautiful objects, but were symbols of his relationship with the world. (An echo of Ransome’s tactile relationship with books crops up in his essay on Izaak Walton, ‘The misprint in the first few copies of his book’. He imagined Walton carrying home from the printers the first copies of his The Compleat Angler (1653), in his pocket ‘where, no doubt, he could touch it with affectionate fingers’.[8])

The most striking illumination of the meaning that Ransome invested in books as objects comes in the sad episode of the fate of his library in the aftermath of his divorce from his first wife, Ivy Walker, at the end of the Great War. Deeply wounded by what she saw as Ransome’s desertion of her and their daughter Tabitha, Ivy refused to allow Ransome to have the library they had built up. Tabitha, from whom Ransome became distant if not estranged as she grew up, entered into her mother’s resistance, and her refusal to allow him to have books he cherished soured a relationship that ended in acrimony after the Second World War. Books – as symbolic and meaningful objects – were central to this sad estrangement.

The sites of Ransome's life and work

Ransome’s relationship to objects is not, it must be acknowledged, the most significant aspect of his life and work. Much Ransome scholarship and the work of enthusiasts and experts deals with his relationships with significant figures in his life – his parents, his wives, his daughter, the Anglo-Syrian Altounyan family (the prototypes for the ‘Swallows’), friends, colleagues, protégés and, not least, readers and admirers. These studies have rightly drawn on the texts of his work, correspondence and memoirs, or on places associated with him. Indeed, an entire cottage industry revolves around identifying, describing and celebrating sites in the Lake District and elsewhere that inspired, correspond to or otherwise evoke places in his novels. It is notable that, among the dozen-or-more sections of the website All Things Ransome, none deals with Ransome realia.[9] Previous writers have explored Ransome’s place in English children’s fiction, his journalism and its political and historical context, including claims that in Russia he worked for the Bolsheviks, or MI6, or both.[10] His passion for sailing and the various vessels that he bought or built, his enthusiasm for fishing – all have been the subject of articles or even books. Mixed Moss (the journal of the Arthur Ransome Society) and the papers presented to the society’s meetings and literary weekends canvass aspects of his life and times, including (for example) discussing the probable actual colour of the telegram that Roger delivers in the opening scene of Swallows and Amazons. (The first page of the novel, however, makes it clear that Ransome saw it as a white telegram in a red envelope: what remains to be debated?)

There is a strong desire on the part of devotees to connect geographically with the man and his stories – characteristically by trying to identify the prototypes of fictional sites, or by visiting his grave at Rusland in Cumbria or the barn at Low Ludderburn where he wrote Swallows and Amazons (as I, of course, also did while visiting the Lake District) – ‘foot-stepping’, as readers of Richard Holmes’s literary biographies would put it.[11] But, despite this desire to travel to the presumptive scenes of Ransome’s novels, no one seems to have enquired about the material traces that Ransome gathered and left. How might an exploration of this material evidence help us to better understand Arthur Ransome the man and writer?

A writer's desk

This analysis could productively begin with the desk on display at the Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry and the adjoining display cabinets. The display is wonderfully evocative for Ransome readers, and includes many items that are recognisable or intelligible to enthusiasts but, from the start, the arrangement raises questions. The museum has clear provenance for the desk, at least. Ransome’s father, the historian Cyril, bought it while he was an undergraduate at Oxford. His widow, Edith, used it until her death in 1944, when she bequeathed it to Arthur. Despite the writer’s tools displayed on it, this was probably not the, or even a, desk at which Ransome wrote anything for publication, and certainly not his children’s novels, most of which were published before he acquired it. The museum acknowledges that he preferred to work at a rather larger desk or table that was usually covered with a baize cloth or even a blanket. The museum’s display is not, therefore, a reconstruction of Ransome’s study, in the manner of a preserved artist’s studio. It is more the museological counterpart of a shrine, though one created as much pragmatically as by popular adulation. Museums deal in space as well as ideas and emotions. Even if a table on which Ransome worked were available, nothing much larger would have fitted easily into the ‘Arthur Ransome Room’ and the museum has wisely preferred the certain provenance of Ransome snr’s table, even though Ransome probably kept it more because of its associations with his parents than for any utilitarian purpose.

photograph courtesy Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry

The items on the desk accord closely with the available descriptions of Ransome’s study, though we need to observe that published accounts may themselves derive from the display in the museum and its predecessors. (The page that his biographer devoted to describing his workroom and methods at least comes from one who witnessed him at work.[12]) Indeed, the documentary evidence supporting a confident view of Ransome’s attitude to material culture is, it must be said, at least ambiguous or partial. For example, in a fragment of manuscript autobiography he described a burglary (in 1932) after which the culprits were arrested rather stupidly trying to put some of Ransome’s Chinese coins into a slot machine.[13] But Ransome’s account is marked by wryness rather than any expression of regret over the loss of his possessions. And yet, the items on display do date, and were kept, from at least the 1920s. They seem to be significant: but why? This article suggests some tentative conclusions, but it has to be conceded that the subject deserves a more rigorous investigation than it has received hitherto; that is, virtually nothing in print.

Even establishing what these objects are is no simple matter. Though the museum’s collection has been devotedly catalogued and described (by museum volunteers Jim and Judy Andrews), the absence of a direct link with either Arthur or Genia has left the museum with little in the way of provenance or explanation for some of the items. Jim Andrews explained that they had ‘no idea what … the various flags meant’ – museum volunteers simply labelled them ‘to be identified’.[14] Recollections can add to the meagre stock of formal documentation. For example, in Ellen Tillinghast’s account of a visit that she made to the Ransomes when they lived in Putney in the mid-1950s, she refers to Ransome showing her model boats – presumably of the Swallow or Amazon, that were given to him by grateful readers, and she mentions seeing several china cats; at least one of which is in the museum’s collection.[15] The authenticity of the objects’ associations with the Ransomes is unquestioned, but the detail is often lacking. Given Genia’s critical, not to say discouraging, attitude to Ransome’s work, it is uncertain what she hoped to convey by the donations. She loved him and was proud of him: but she seems to have deprecated much of his work – especially the children’s novels – and may not have wished to preserve items that Arthur valued. It is impossible to be certain without a more searching examination of the ambiguous evidence than I was able to devote to the question. There are hints in a recollection by Ransome’s niece, Helen, that the process by which mementos survived was (as so often happens) haphazard. She recalled that, when relatives were ‘settling up’ after Genia’s death in 1973, she and her siblings ‘asked for a box of oddments … rather than it should go to a house clearing sale’.[16] That the ‘oddments’ included the flag of the Slug, Ransome’s first boat, which he sailed in the Baltic in the unsettled years after the Great War and which is now held by the museum, suggests that the collection was not assembled or acquired with great preparation or forethought in the Ransomes’ lifetimes. (That Genia made the flag suggests one explanation for its preservation in the museum’s collection.)

The items in the museum’s custody fall into several categories. As we have seen, some are the tools of a writer’s work – the Remington Home Portable typewriter and its ribbons. Others, though also utilitarian, reveal facets of the man. The pencil tray, for instance, was used for years, packed and transported as the Ransomes moved from house to house, from the Lake District to East Anglia, to London and back to the Lake District. The pencil is enclosed by an elaborate Turk’s head – an ornamental string knot – which is described as a practical way to stop the round pencil from rolling, certainly, but is also a tiny symbol of the nautical crafts that Ransome celebrated in his work, notably in Peter Duck, whose eponymous central character is an ‘old salt’. Ransome, we infer, valued order and habit: that he surrounded himself with familiar tokens is apparent from the keepsakes he displayed on his desk.

The most numerous single category of item on the desk are his pipes: no fewer than 17 are displayed, and another couple of dozen lie in a box labelled ‘Miscellaneous’ in the museum’s store. Ransome was, as the museum’s caption avers, ‘an avid smoker’. They, and the ‘folk art’ carved wooden ashtray he obtained in Russia, hint at the value he accorded to smoking as a ritual and a statement of his identity as a bookman or country gentleman, as well as a confirmed addict. Their number also hints at his capacity for fussing over matters that others might disregard as being unimportant: surely no one actually needs several dozen pipes. But the pipe, and what it represented – solid, dependable, unhurried, companionable, and thoroughly English – mattered to Ransome. Ransome’s pipes not only represent the only artefacts that Mixed Moss has noticed or illustrated in 20 years, but Rodney Dingle’s 2003 article ‘A puff for the master’s pipe’ stimulated spirited responses correcting his assertions about the depiction of smoking in Ransome’s novels.[17] The rejoinders from informed readers included statistics from a Texan devotee who had re-keyed the texts of all Ransome’s novels and was therefore able to state exactly how many times Ransome mentioned smoking in his oeuvre. But, apart from this (and possibly an article about the prototype of the car driven by Mrs Blackett, the Amazons’ mother, known in the books as ‘Rattletrap’), few other contributors have explored the significance of the things that Ransome valued. There is a need for further research, perhaps drawing on the collective expertise of contributors to Mixed Moss and others.

Ransome realia

Much of the surviving Ransome realia relates to his life before he began his children’s novels, in his mid-40s. As a foreign correspondent, Ransome witnessed and reported on the turbulent events in Russia between 1917 and 1925. He met and interviewed Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky and other Bolsheviks, and one of Trotsky’s secretaries, Evgenia Shelepina, became his mistress and, in due course, his second wife. In 1920, in the turbulent aftermath of the Russian Revolution, he returned to his Petrograd (St Petersburg) apartment to find that his belongings had been ransacked by Bolshevik officials. A mob had stolen his possessions and destroyed a precious collection of newspapers. All he retrieved was a Turkish coffee mill and a set of cups (curiously – as metal objects they must have been portable, but perhaps a tea-drinking mob did not see them as useful). These few items are also part of the museum’s display – Ransome evidently treasured them as keepsakes of his Russian years as an intrepid foreign correspondent for the Manchester Guardian.

These items include, for example, objects identifiable as having been kept by Ransome for many years – almost 50 years from their acquisition to his final illness. The collection on the desk includes two brass candlesticks with detachable saucers. The museum’s card index and caption suggests that Ransome used them on otherwise unilluminated trains in Russia during the Great War. They remained in use in his workroom for years after; and presumably not just because the electricity supply at Low Ludderburn and other remote homes was unreliable. In the same category is the Turkish coffee mill, also on display.

The item on the desk that is superficially the most baffling is, perhaps, the one that provides the clearest clue to his character, his work and, indeed, the mainsprings of his life. It is a grey stone several centimetres long, with a hole bored through it, threaded with a white cotton ribbon. This is described as a ‘dobbie stone’ – a talisman – from the top of the Old Man of Coniston, the 803-metre-high peak that can be seen from all over the Lake District. The peak features in Swallowdale as ‘Kanchenjunga’, which the Swallows and Amazons climb as the precursor to the novel’s dramatic denouement. Coniston in Cumbria had a particular significance for Ransome. Cyril Ransome is said to have carried little Arthur to the top of the mountain when he was a few weeks old, an event that is rightly regarded as significant by those who have recounted his life. To Ransome the stone expressed the mystical bond he felt with the Lake District, by holding a small piece of it wherever he was (which was more often than not somewhere else). Later in life, as his infirmities prevented him from walking about his beloved lakeland countryside, the stone enabled him to possess a piece of his country. This dobbie stone may have been to Ransome the single most important item in the entire collection.

Whatever else it means, this eclectic if, at times, baffling collection suggests that things mattered to Ransome and that he actively and even consciously set out to acquire things because of the associations that they evoked. That he appears to have had them before him on the desk at which he wrote (and not on shelves, out of sight, as it were) emphasises their importance. We do not know definitively whether he used these items actively. Did he look at them and recall times very different to his quiet lakeland life, when he visited exotic and even dangerous places as a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian? Did he toss the coins to make decisions? Did he touch or fiddle with them, as a displacement activity when words would not come (which was often – Ransome wrote slowly, dogged by Genia’s criticism)? The much-handled plaster cat suggests that his contemplation of his artefacts was more than merely visual. (The plaster cat, a souvenir of his last assignment as a political reporter, in Egypt, is also a reminder to us, as their nephew Arthur recalled, that they kept a succession of ‘beautifully silver tabby cats’.[18]) It is possible that careful scrutiny of the many photographs of the Ransomes in their various houses in Britain (especially those that are held in the Brotherton Library, which I visited too briefly to conduct such a study) might reveal further evidence.

photograph courtesy Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry

The literary uses of objects

But, if a study of the objects themselves suggests that Ransome valued objects for particular reasons, a study of the texts of the five ‘lake’ books suggests a more qualified conclusion. Initially it would seem that an object – a boat – inspired the entire project. Roger Wardale identified the moment at which Ransome conceived what became Swallows and Amazons. While sailing his boat the Swallow in Bowness Bay on Lake Windermere in 1929, Ransome had ‘the idea of writing a book in which the heroine would be the little boat itself’.[19] Close readings of the Swallows and Amazons novels (Swallows and Amazons, Swallowdale, Peter Duck, Winter Holiday, Pigeon Post, We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea, Secret Water, Missee Lee, The Picts and the Martyrs and Great Northern?) suggests that objects seldom figured significantly in their plots, though they are replete with references to the impedimenta of boats and related pursuits: camping, mining, fishing, birdwatching and photography.[20]

Objects were, however, often integral to Ransome’s meticulous descriptions of local settings. ‘There was a grandfather clock in the corner with a moon showing in the circle at the top, and a wreath of flowers round the clock face’, he begins a description of the Swainsons’ farm kitchen in Swallowdale.[21] With the possible exception of the boats themselves, however, very few points in his novels’ plots turn on objects as such. The few exceptions include, for example, Titty’s use of a waxen figure of the obnoxious Great Aunt in Swallowdale, and Captain Flint’s ‘treasure’ in Swallows and Amazons (which turns out to be the manuscript of his autobiography). Ransome’s text, footnotes and illustrations, however, reveal how important technical and, especially, nautical knowledge was to the books’ atmosphere (and, indeed, their appeal). Ransome included many descriptions of equipment or tools, such as the salvaging of the Swallow in Swallowdale and, later, the shaping of its new mast; a footnote explaining a ‘quant’ (that is, a pole to propel a wherry) in Peter Duck; and many incidental illustrations including ‘How a sea-anchor works’, ‘Bowline knot’, ‘Riding light’, ‘This is a bollard’ and (from Pigeon Post) ‘Dick’s bell’. They collectively suggest that he was interested in depicting items, such as lanterns or compasses, in order to impart the knowledge on which readers’ comprehension of the action depended, and to foster the nautical lore that give the lake novels their particular tone. Indeed, the first novel begins with Roger, the youngest Walker boy, ‘tacking’ against the wind as he runs to Holly Howe farm to collect the telegram from their naval officer father authorising them to embark on the expedition to Wild Cat Island that becomes the focus of the story. Both his novels and other writings suggest that Ransome cared about things as symbols of ideas, emotions or experiences; indeed, the evidence suggests that he invested greatly in physical objects and accorded them profound significance.

Many of the items on display in the museum’s Arthur Ransome Room might be regarded as little more than souvenirs, either collected by Ransome in his travels (as a correspondent he reported from China, the Sudan and Egypt as well as Russia). Other items seem to have been given to him by readers and admirers as tokens of appreciation. They include models of the boats featured in the books. Still others reflect Ransome’s interests, especially sailing, fishing and chess. The museum displays items that are symbolic of his pursuits and reflect his favourite pastimes – a sail-maker’s kit, a fishing reel, the travelling chess set he used on various journeys. It also holds many flags associated with Ransome, including burgees flown on several of his boats, and a replica Jolly Roger, provenance unstated. Much about them, as so often in material culture studies, remains necessarily conjectural, informed by documentary evidence in published works and in the collections of the museum and the Ransome collection in the Brotherton Library, Leeds.

The Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry also holds, but does not display, one of the most significant of the several awards that Ransome earned – the inaugural Carnegie Medal, awarded by the Library Association in 1938, ostensibly for Pigeon Post, though effectively recognising the achievements of his first decade of children’s novels as a whole. Again, the handsome medal raises questions. What did he – what does any author – do with such an award? (It cannot be worn, but was it ever displayed? Ransome family photographs might offer clues.) Though chronically lacking in confidence, Ransome was far from modest, and he was ambitious and rightly stubborn over royalties and rights: but did he display the medal? As so often in material culture studies the object itself offers no clues to its use. The location of Ransome’s other awards – the testamur of his honorary doctorate from Durham and his CBE, is unknown.

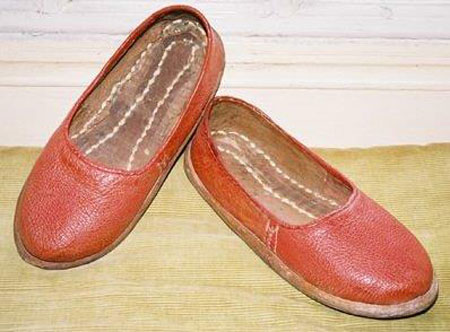

Still, it is clear that some of the items in the display cabinet are of great import in the story of the making of Ransome’s novels and, indeed, in the making of Ransome the novelist. Ransome scholars now express reservations over the several explanations that Ransome gave of the origins of his lake novels (and therefore of his transformation from jobbing journalist disillusioned with the life of a foreign correspondent into one of the 20th century’s most highly regarded English children’s authors). In reply to requests from readers, and even more pressing demands from his publishers, Ransome offered several explanations, ranging from the mystical (he wrote that whenever he returned to his beloved Coniston he felt compelled to ‘dip my hand in the water, as a greeting to the beloved lake’) to the frankly unbelievable (‘it almost wrote itself’).[22] But, one account that needs to be interrogated relates strongly to significant objects – the pair of red slippers – displayed in the Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry.

photograph courtesy Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry

Ransome and the red slippers

For 20-odd years, from 1930 to 1947, Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons carried the dedication ‘TO THE SIX FOR WHOM IT WAS WRITTEN IN EXCHANGE FOR A PAIR OF SLIPPERS’. ‘The six’ were the children of Ernest and Dora Altounyan, friends of Ransome through the Collingwood family, with whom he had shared lakeside holidays 25 years before. Ransome’s relationship with the Altounyans prompted the story and, perhaps, gave him a pretext to write a children’s book. But, they were not, it seems, the literal inspiration for the Walker children (curiously, his ex-wife’s maiden name), even though Ransome borrowed most of their names for his characters. The day after Ransome’s 44th birthday in January 1929 the Altounyan children presented him with a pair of red slippers (‘the handsomest slippers that anyone ever saw’, he said). Ransome conceived the idea of a novel that would entertain the children when they were at home in Syria. He wrote what became Swallows and Amazons (the ‘Amazons’ were inspired by the sight of two red-capped girls beside the lake) over the ensuing year, and it appeared in July 1930.

The Altounyans (whom Ransome helped to teach to sail, in a boat named Swallow), naturally identified with their fictional representations – ‘the story must surely be about us!’, the eldest daughter, Taqui Altounyan, remembered.[23] The Altounyans, however, living mostly in distant Syria, grew older, and other children displaced them as Ransome’s companions in boat-based adventures, notably on the Norfolk Broads, the setting of several novels written in the mid-1930s. Increasingly and irrationally exasperated with the Altounyan family’s justifiable belief to be the literal prototypes of the adventurous children who had populated his novels, Ransome brooded on their seeming presumption and later withdrew the dedication from the books, which have since been reprinted many times. The presence of a pair of red slippers in the Arthur Ransome Room offers a reminder of the part played in the story by what, regardless of Ransome’s falling out with Ernest Altounyan especially, surely became a treasured possession in the Ransomes’ several homes. Surely: except that they are also now a reminder not just of Ransome’s friendship with the family, but also of his estrangement from them.

Indeed, it turns out that the slippers on display are in fact not the original slippers at all, but a pair donated to the museum by one of the adult Altounyan children.[24] What happened to the originals? At present it is impossible to say, but it is possible that either Arthur or Genia discarded them, perhaps a sign of the depth of his feelings over the Altounyans. As is so often the case, a physical object represents powerful human emotions. The slippers, treasured as an expression of friendship, were lost amid feelings of hurt and resentment. Their absence speaks of alienation of affection just as their presence symbolised the relationship between Ransome and the Altounyans.

It must be admitted that much of this analysis rests on certain assumptions. The material is on display in the Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry because Genia, between Arthur’s death (1967) and her own (1975), donated material to the museum, then being established, while other material came from other sources, such as friends and admirers of Ransome’s work. As is often the case, the museum’s curatorial records do not contain detail on the provenance of all the items in its custody.[25]For the most part they comprise typed cards that describe the items, with a frustrating lack of additional, contextual or other detail. Either Genia was too frail or forgetful to explain their provenance, or she had never taken a great deal of interest in what she disdained as her husband’s ‘toys’. (By the time she donated them Arthur had not worked as a writer for over a decade, and the heyday of his career as a children’s novelist lay more than 25 years in the past.) Moreover, the Ransomes had moved frequently since Arthur had wrestled with successive manuscripts of his novels: who is to say that the objects now on display were arranged the same way as the years advanced and as the Ransomes often moved house?

An incomplete material record

There are also omissions and complexities in the material record of Ransome’s life. Much of it was lost either in the course of the Ransomes’ peripatetic life, or from Genia’s neglect in her old age after Ransome’s death. Some of it is not held in museum collections; some of it, indeed, is still used. Several of the vessels he commissioned or owned, for example, still exist. The cutter Goblin, the setting of We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea, named by Ransome Nancy Blackett (after the older of the two ‘Amazons’), is still afloat in the custody of a trust, while the boat Mavis, the inspiration for the original Amazon, was on display at the recently closed Windermere Steamboat Museum and is now on loan to the Ruskin Museum at Coniston. Mavis’s restoration in 1989 led to the creation of the Arthur Ransome Society.[26] Other boats are in private hands. Ransome’s boats, fictional and real, are abundantly documented, not least through the splendidly authoritative website All Things Ransome and the associated and expert TarBoard discussion forum.[27]

Other aspects of Ransome’s life, even ones of profound and daily importance to him, are physically undocumented. For example, Ransome’s indifferent health – his papers make clear that he was a martyr to piles, ruptures, ulcers, knocks, falls and injuries of all kinds – was touchingly documented by Genia in an account that was added to Ransome’s autobiographical papers. But, she understandably did not preserve any of the numerous bottles of bismuth or trusses that must have made their way into their homes over the years. Instead, it is to Ransome’s literary life in particular that we must seek illumination from the material record.

Genia deprecated Ransome’s tendency to acquire things, perhaps because (as Diane Janes pointed out in a refreshingly astringent reappraisal of Genia’s part in the relationship in 2006) it fell to her to keep their houses clean and tidy.[28] In the late 1920s she wrote to him tartly while he was away on one of his last jobs for the Manchester Guardian. As well as complaining of not receiving letters (a common theme in her correspondence) she described having been ‘working like a slave’, harassed by ‘such a beastly depressing job going through cupboards & drawers and old letters and trying to clear out all rubbish which you in particular seem to accumulate in staggering quantities’.[29] Ransome, however, doubtless accumulated more. In 1957 Maurice Rowlandson wrote to him to express his admiration for Ransome having inspired him to organise boating holidays for boys on the Norfolk Broads. As well as expressing what Ransome would by then have regarded as an uncongenial curiosity over the prototypes of places in his novels, Rowlandson recalled having met Ransome at Pin Mill in the 1950s. Ransome had shown the young Maurice his ‘treasures’ – presumably including the objects now displayed in the Ransome Room.[30]

Curious readers of Ransome have arguably always, like Ransome, been more interested in people, places and relationships than in things. (In places above all – articles speculating and justifying the supposed actual locations of incidents in his novels remain a staple of Arthur Ransome Society members’ interests, and this interest has fuelled several books.) While Owen Roberts contributed an insightful attempt to reconstruct the look, sound and even smell of the lake country that Ransome knew and loved, Christina Hardyment, doyenne of Ransome studies, made the profound observation that ‘Ransome country was … a state of mind rather than a place’.[31] To this degree it exists above the mundane reality of enthusiasts seeking to identify prototypical sites. Taking an interest in the material evidence of imagination could be regarded as either prosaic or irrelevant.

Conclusion

What are we to make of this survey of the material remains of Ransome’s life and work? It demonstrates the relative paucity of material compared to documentary evidence. For all the interest his artefacts might evoke, it is clear that the more informative and expressive evidence remains, as so often, that which speaks directly of the man, his emotions and relationships. In this, the published texts of Ransome’s novels remain supreme. He created vivid characters and engaging plots and, even though the characters, settings and plots may increasingly seem dated, the achievement of envisaging children embarking on outdoor adventures, which was something that children’s literature had barely done before Swallows and Amazons. (And, especially, in groups of boys and girls: it is notable that the balding, bespectacled, pipe-smoking, tweed-clad, chess-playing, fly-fishing Ransome was an unlikely seeming pioneer of gender-neutral children’s fiction.) Still, enough survives and is conducive to analysis to suggest that the material culture that Ransome collected, and which now forms part of the evidence bearing upon his life and work, can reveal insights unsuspected in words.

What remains of the material evidence of Ransome’s life and work reminds us of what interested, preoccupied and motivated his work. Even the offerings of his readers illuminate, in a different way to the surviving correspondence, the effects that his work had on generations of readers. As ever, a fully rounded appreciation of an author requires the deployment of a range of evidence – literary, documentary, even the physical in his homes and the landscapes he loved – as well as the material. It is thus in the round that we can truly comprehend and understand him.

courtesy Penguin Random House

As Ransome’s biographer, Hugh Brogan, observed, ‘the lakes … always brought out the best in him’.[32] For me, then, the most significant object in the Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry’s Ransome collection is perhaps the most unprepossessing, the dobbie stone from Coniston. It fittingly represents the profound, mystical attraction the lake country had on a man throughout his life, symbolising the far-reaching consequence of a relationship between man and place in time. Is it a coincidence that, in describing the creation of Swallows and Amazons – his first ‘creative’ work after years of what he called ‘discursive’ writing – Ransome should have described the book as ‘the real touchstone’ of the change in his life that he embraced in 1929?[33] Perhaps the dobbie stone also represented the physical embodiment of a book whose creation, and all that followed, changed his life and so much enriched the lives of perhaps hundreds of thousands of readers over the succeeding nine decades?

This article has been independently peer-reviewed.

Endnotes

1 Rupert Hart-Davis (ed.), The Autobiography of Arthur Ransome, Jonathan Cape, London, 1976, p. 15.

2 Arthur Ransome, The Picts and the Martyrs or, Not Welcome at All, Jonathan Cape, London, 1943, p. 133.

3 This article is a further (seemingly final) product of the ‘Material Histories’ project of the Research Centre of the National Museum of Australia, an enterprise that seeks to explore and emphasise the significance of material culture in historical studies, integrating social, environmental and cultural studies. I am grateful to my former colleagues in the Research Centre for their comments on earlier drafts. I am especially grateful to James Arnold and Rachel Roberts of the Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry, and Kasia Drozdziak of the Brotherton Library Special Collections at the University of Leeds for their assistance in facilitating access to the Ransome material in their respective collections; and to Dave Thewlis of the Arthur Ransome Society’s TarBoard discussion forum. Thank you, too, to the two anonymous referees of this paper whose comments were particularly useful.

4 Christina Hardyment, Arthur Ransome & Captain Flint’s Trunk, Frances Lincoln, London, 2006, p. 57.

5 Arthur Ransome, Mainly about Fishing, Adam & Charles Black, London, 1959, p. xiv.

6 Roger Wardale, Arthur Ransome: Master Storyteller, Great Northern Books, Ilkley, 2010, p. 39.

7 Hart-Davis The Autobiography, pp. 331, 335.

8 Ransome, Mainly about Fishing, p. 145.

9 www.allthingsransome.net/

10 Roland Chambers, The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome, Faber, London, 2009.

11 The British literary scholar has turned the practice of literary tourism into a respectable methodology – see his Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer (Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1985).

12 Hart-Davis, The Autobiography, pp. 289–90.

13 Manuscript autobiography, Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry, Kendal, Cumbria.

14 Jim Andrews, ‘Treasures from a certain trunk’, Mixed Moss, vol. 3, no. 1, 1997, 17–18.

15 Ellen Tillinghast, ‘Tea with the Ransomes’, Mixed Moss, vol. 1, no. 3, 1992, 5–10.

16 Helen Lupton, ‘Big, tweedy and bristly’, Mixed Moss, new series, no. 1, 2001, 6.

17 See Rodney Dingle, ‘A puff for the master’s pipe’, Mixed Moss, no. 4, 2003, 36–37; and the responses collated as ‘Put that in your pipe, Rodney …’, Mixed Moss, no. 5, 2004, pp. 63–64.

18 Arthur Lupton, ‘A nephew’s view’, Mixed Moss, new series, no. 1, 2001, 3–5.

19 Roger Wardale, In Search of Swallows & Amazons, Sigma Leisure, Wilmslow, 1996, p. 31.

20 Those unfamiliar with the detail of Ransome’s novels will find a good summary in Peter Hunt’s Arthur Ransome (Twayne Publishers, Boston, 1991, chpt. 4, ‘Introducing the “Swallows and Amazons” series’).

21 Arthur Ransome, Swallowdale, Jonathan Cape, London, 1931, p. 124.

22 Hart-Davis, The Autobiography, pp. 26; Brogan, The Life, p. 430.

23 Brogan, The Life, p. 311. Taqui’s gender was transposed for Ransome’s fictional purposes, but the Swallow’s crew included Susan, Titty and Roger, the names of three of the Altounyan children.

24 Advice from Rachel Roberts, Lakeland Museum of Life and Industry, 16 January 2016.

25 The Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry advises that it would be happy to hear from anyone who may be able to add to the records of its Ransome collections. It can be contacted through its parent organisation, Lakeland Arts, at info@abbothall.org.uk

26 A museum devoted to the life and work of John Ruskin might seem an odd place to display a boat, but the connection rests with Dora Altounyan (to whom Ransome had once proposed) who was the daughter of William Gershom Collingwood, Ruskin’s amanuensis.

27 allthingsransome.net/arboats/index.html

28 Diane Janes, ‘Evgenia – a woman much maligned?’, Mixed Moss, 2006, 34–40.

29 Evgenia Ransome to Arthur Ransome, undated, Box C4, correspondence, BC MS 20c, Brotherton Library.

30 Maurice Rowlandson to Arthur Ransome, 15 November 1957, Box C4, correspondence, BC MS 20c, Brotherton Library Special Collections, University of Leeds.

31 Owen Roberts, ‘A view of the lakes – some thoughts’, Mixed Moss, 2008, 2–6; Christina Hardyment, Arthur Ransome, p. 81.

32 Brogan, The Life, p. 413.

33 Hart-Davis, The Autobiography, p. 335.