Are young children welcome? The state of play in art museums and galleries in New Zealand

Abstract

New Zealand museums, like their international counterparts, have engaged in a debate about improving access, and attracting wider and more diverse audiences. However, in all of the debate about access, the institutional power of art museums and galleries to include or exclude certain groups of visitors, and the different needs of visiting populations in New Zealand, there is little mention of issues of access for pre-school children in these settings. This article explores the findings from a recent survey of 17 of New Zealand’s largest art museums and galleries. The survey sought to examine the relationship between these institutions and the early childhood sector, the types of provision for guided and self-guided visits by early childhood groups, and the types of educational services and/or resources that can assist early childhood teachers to make the most of art museums. The findings indicate that the New Zealand Government’s current Learning and Education outside the Classroom funding regime discriminates against the early childhood sector’s use of art museums and galleries, and thus significantly limits access for young children. Nonetheless, some institutions do welcome visits by children attending early childhood centres, and several have programs for children and their families. Improvements in marketing to the early childhood sector, the development of teaching and visit-related resources tailored to the sector, and professional development offered by art museums and galleries for early childhood teachers could, however, also make a positive contribution to improving access for young children.

Introduction

The role of education in art museums has been a vigorously debated topic both in New Zealand and internationally. Research into the characteristics of art museum and gallery visitors has been important for shaping educational programs that respond to the needs of current and potential audiences. A seminal study by Bourdieu and Darbel, for instance, into the characteristics of the European art museum-going public in the 1960s suggested that dispositions towards, and understanding of, art works were shaped by education, social conditioning and class.[1] They believed that education could help to break down barriers and assist visitors in gaining intellectual access to art collections, and that schools could, and should, play an important role in this process.[2]

The debate about best practice in art museums and galleries continued into the latter part of the twentieth century and was often controversial; it was designed to provoke and challenge traditional approaches to the purposes of art museums and their educational practices. In the late 1980s Wright stated:

The present fiction in museums – that every visitor is equally motivated, equipped and enabled ‘to experience art directly’ – should be abandoned. It is patronising, humiliating in practice, and inaccurate … something more than the traditional ‘hands-off’ approach is called for.[3]

This withering critique of English art museums and galleries was associated with the call for a ‘new museology’, one which demanded a ‘radical re-examination of the role of museums’[4] and a rethink about their purpose in contemporary Western democratic societies.[5]

Consequently, over the past three decades art museums and galleries have made considerable efforts to become less elitist and, increasingly, more accessible. Ross,[6] for instance, argues that the ideas and values embedded in the new museology, and the political and economic shifts towards more market-based approaches, have created ‘a new climate of audience-awareness and reflexivity’, which has encouraged many institutions to diversify and make themselves more representative of their communities. This view is supported by Xanthoudaki, Tickle, and Sekules, who, referring to museums in Europe, Asia and North America, believe that while ‘in the 1980s there was urgency about using educational visits to increase visitor numbers, the following decade saw an increasing interest in questions of intellectual and physical access’.[7] Furthermore, they argue that increasingly museums ‘began to recognise their potential as stimuli in the fields of formal and informal education’. Illeris has also observed this trend in Denmark: ‘The introduction of experimental educational settings is related to an important tendency among Western museums to initiate radical changes towards more inclusive practices, based on dynamic and complex understandings of the relationship between learning and social change’.[8]

New Zealand art museums and galleries, like their international counterparts, have also engaged in debate about improving access and attracting wider and more diverse audiences. This is now a fundamental aim identified in many museums’ codes of ethics (see, for example, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa’s Code of Ethics for Governing Bodies and Museum Staff[9]). Developing inclusive relationships with Māori, the Indigenous people of New Zealand, has been at the forefront of much of the debate about issues of access and participation (see, for example, the studies by McCarthy[10]). Some researchers argue cautiously that there have been some encouraging moves to address issues of power inequities in the nation’s national museum, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, in relation to Indigenous issues.[11] Hakiwai believes that there are still significant issues for a true Māori sense of legitimacy in many of New Zealand’s museums, but also feels there have been some constructive institutional changes.[12] He recognises that some museums are being proactive by employing Māori staff, establishing tribal networks in order to work more effectively with Māori, and developing great awareness of Māori cultural values.[13]

In all of the debate about access, the institutional power of art galleries and museums to include or exclude certain groups of visitors, and the different needs of visiting populations in New Zealand, little mention is made of issues of access for pre-school children (under 5 years) in these settings. The types of educational programs or initiatives that best suit their needs are largely neither contested nor even debated. Mason and McCarthy’s investigation into why youth were under-represented at the Auckland Art Gallery is one of the few examples of research examining the needs of non-adult visitors.[14] They concluded that New Zealand’s art museums need to assess their art exhibitions and the gallery environment to determine how ‘user friendly’ they are for all visitors, particularly for young people. A recent literature review and investigation into issues of access for pre-school children in New Zealand suggests that, while art museums in other countries have made some efforts to be more inclusive of this age group, young children attending early childhood (EC) services in New Zealand,[15] like youth, also constitute an under-represented group of art gallery visitors. However, the review determined that more research was needed to fully examine the barriers and facilitators that affect access for this group of young visitors.

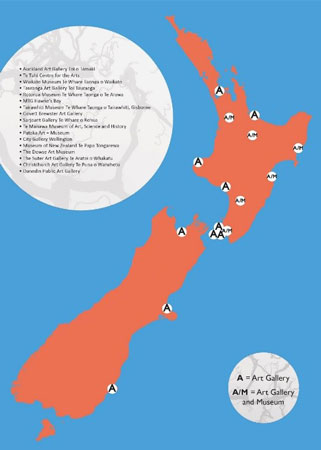

This article explores the findings from a survey undertaken in 2013 of 17 of New Zealand’s largest art galleries and museums.[16] The survey sought to examine the relationship between these institutions and EC centres (which cater for children from 0 to 5 years of age), the types of provision for guided and self-guided visits by EC groups, and the types of educational services and/or resources that can assist EC teachers to make the most of art museums and galleries. The survey constitutes an important facet of my current doctoral research, which is investigating the use of art museums and galleries by the EC education sector in New Zealand.[17] It is important to note that not all of the institutions involved in the research hold collections that comprise only works of art. Six institutions hold other types of collections as well; for example, historical and scientific collections. How the institutions describe themselves also varies (museums, art museums, art galleries).[18] Nonetheless, all of the institutions surveyed employed educators to work with children.

Young children visiting art galleries and museums

Considerable international research has shown that young children benefit from learning experiences in art museums and galleries.[19] This view is also supported by researchers in New Zealand and Australia, who have found that art museums/galleries can provide young children with important opportunities for exploration across a range of learning domains: cognitive, aesthetic, affective and kinaesthetic.[20] For example, Carr, Clarkin-Phillips, and Paki note that art museums/galleries also provide significant opportunities for young children to learn about a nation’s social and cultural history.[21] Learning dispositions, such as curiosity and receptivity to new ideas and the disposition to visit art museums and galleries, are best fostered and enhanced when young children are able to visit these institutions.[22] This benefits not only the children but also the art museums and galleries, who are increasingly looking to develop their audiences.[23]

Hipkis argues that helping students to engage critically in learning is important for assisting with the development of key competencies, such as, using language, symbols and texts, thinking, participating, contributing, managing oneself and relating to others.[24] These are competencies identified in the New Zealand curriculum[25] and in the New Zealand EC curriculum, and can be used successfully by art educators in art museums and galleries to guide and inform their teaching programs. Bowell agrees, and suggests that because visual art learning experiences such as those experienced in art museums or galleries play an important role in ‘developing critical awareness and creativity’, such skills are transferable to other knowledge domains.[26]

photograph by Lisa Terreni

The New Zealand EC curriculum document, Te Whāriki,[27] and the Australian EC curriculum, Belonging, Being & Becoming,[28]encourage EC teachers to provide programs that enable pre-school children to develop knowledge, skills and experience in visual art; for instance, by providing learning experiences that will help young children to develop familiarity with different types of art and give them opportunities to develop skill and confidence in a variety of art-making processes. Thus, art museums and galleries are fertile resources for teachers and children, providing unique opportunities for stimulating imagination, thinking and understanding.[29]

The art museum and gallery survey

In order to ascertain the degree of engagement the art museum and gallery sector currently has with pre-school services in New Zealand, an in-depth survey was undertaken involving leading personnel at 17 of New Zealand’s largest art galleries and museums. It was felt that a personal, one-to-one approach would be more effective for eliciting relevant answers to the survey questions, and for creating opportunities for discussion about issues relating to EC access. Copies of the questions were emailed to participants in preparation for the discussion.[30]

Building relationships with art museum and gallery personnel proved to be an effective way of gathering data. In most cases the survey was completed with the institution directors. However, if they were unavailable, other key staff were involved, such as education managers or public program leaders. In most instances, the institution’s educators were also present at the meetings. What was apparent from the start of the survey process was their willingness to engage with the research. There was a high degree of interest in the topic, and the responses to the questions about EC participation and access (or lack of it) were, mostly, encouraging despite the identification of barriers posed by deficiencies of funding, time or resources. For example, one enthusiastic director stated, ‘having pre-schoolers and activities in the gallery is an area of growth and need. A gallery is a good fit for this as they can always be fun, educational, and great learning spaces’.

graphic by Jane Barrett

Twenty-eight questions probed a range of topics relating to visits by groups from the EC sector or by families during the past year. The survey was created as a means of eliciting basic statistical information; for instance, numbers of educators employed by the art museums/galleries, numbers of school and EC centre visits, and numbers of visitors under 5 years old. However, more open-ended questions were also asked in order to determine attitudes and beliefs about the role of art museums and galleries in visual art education for young children, and about the real, or perceived, barriers to working with the EC sector. Because the data pool was small, simple pattern coding (that is to say, ‘coding that is inferential and explanatory’[31]) and basic matrices were used to classify the themes emerging from the research, and to interpret some of the statistical data. The questions asked in the survey determined some of the emerging themes, but new themes also emerged from comments made by participants during the survey process.[32] The themes that emerged from the survey included: the different ways EC groups visit art galleries and museums, the educational approaches of art museums and galleries, exhibition and education program marketing, teaching resources, professional development for teachers, and the facilities available for family groups.

Funding of New Zealand art galleries and museums

After careful consideration of the data and how to present it effectively, it became clear that a discussion of the funding arrangements for art galleries and museums needed to be discussed first, in order to make other information elicited from the survey clearer for the reader. Nearly all of the art museums and galleries at the time of the survey were primarily funded through their local, regional or city councils, with the exception of the national museum, which received direct government funding. Grants, sponsorship, donations, user-charges for exhibitions and art classes and, sometimes, research grants were other funding sources that were identified. Many of the institutions, but not all, were free for self-guided visits by their local communities, although specialised exhibitions (for example, travelling ‘blockbusters’) generally had an entry charge.

Government funding, through the Ministry of Education, of the Learning Experiences Outside the Classroom (LEOTC)[33] scheme supports many curriculum-related programs run by a range of community-based organisations throughout New Zealand, including art galleries/museums. Such funding enables the organisations to employ educators to work with primary and secondary schoolchildren. It is important to note that it is restricted to these sectors, which may prevent educators from working formally with the EC sector. Fifteen of the 17 art museums and galleries surveyed received LEOTC funding. LEOTC funding restrictions were identified by all of these institutions as a major barrier to the EC sector’s access to the education services they provide. Nonetheless, some art gallery and museum staff felt that having council funding sometimes gave them a little more leeway for working with EC centres.

Numbers of art educators and visits by children

This section of the paper discusses the data in relation to the number of art educators employed by art museums and galleries to work with children. It also examines data in relation to the number of visits by children under 5 years of age, and those of schools and EC centres. The data set creates a statistical snapshot of these facets of the institutions at the time of the survey.

Educators

Initial questions in the survey asked about the number of educators employed by the art museum or gallery and about how these positions were funded (as noted earlier, five of the 17 art institutions surveyed can be classified as general museums that hold art collections, and their educators are often generalists rather than dedicated art educators). The relative size of the institutions and their funding arrangements reflected the number of art educators employed. The two largest art institutions, based in the biggest cities, employed between six and ten educators (but not all positions were full-time or permanent); the smaller art museums or galleries in provincial towns employed, on average, one to three educators, and again not all were necessarily full-time positions.

School and early childhood centre visits

It was difficult to identify the precise number of schools and EC centres with which the art museums and galleries interacted during the year. What became clear through the survey process was that it is the number of schoolchildren involved throughout a year, rather than the number of schools, that is used to measure target requirements determined by LEOTC funding. Consequently, the number of schools that visited did not necessarily reflect the number of schoolchildren who visited and with whom the educators worked. As one director noted, one school had booked an entire week of their program, but as the children came from a series of different classes the total number of children catered for was quite large. Overall, from the figures received, the data indicated that hundreds of primary and secondary schoolchildren undertook programs in the art museums and galleries context throughout the year. For all of the art museums and galleries, schoolchildren constituted one of the largest groups of visitors.

Most of the personnel involved in the survey initially reported that they did not, and could not, work with EC groups owing to LEOTC funding constraints but with further probing most revealed that they did in fact work with these groups, although only infrequently. The survey revealed that EC centres had visited 15 out of the 17 institutions over the past year. Some of the institutions knew how many times EC groups had visited throughout the year, while others did not, and this uncertainty is largely because of the nature of visits by the EC sector. Self-guided visits, for example, tend not to be counted by the institutions. However, figures are usually kept for guided visits (for example, EC groups working directly with art educators, public program staff, or docents), which resulted in some places reporting no visits by EC groups ranging to one museum reporting 20 (still proportionally very much lower than the numbers of school visits). However, despite the actual numbers of EC groups visiting, what was clear from the survey was that the attitude of the art museums and galleries to working with the sector also determined whether they worked with EC groups; some expressed reluctance or uncertainty and were less inclined to work with EC groups, but others enthusiastically accommodated them, welcoming their participation.

There were some interesting variations in approaches to accommodating EC groups. For instance, one of the larger art galleries had run a pilot project to work with EC groups throughout the year. This was unlikely to continue, however, because of a lack of funding for staffing the development and delivery of these programs. The loss of the staff member who had the skills to work with this age group was also a factor. The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa had specifically employed an EC educator with the brief to develop programs that better suited the EC sector, and increased access to exhibitions already appears to have resulted from this initiative.[34] However, this institution is not reliant on LEOTC funding. One art museum has a user-pays system for educator-led visits and, consequently, is willing to work with any education sector group, and two galleries felt that they accommodated EC groups under their public programs mantle. One art educator had not really thought about the EC sector as a specific target audience because of the institution’s focus on family-oriented exhibitions and activities, which were seen as the way to cater for young children. Working with home-schooling groups was identified by one gallery as their way to include young children in their education programs.

Visits by children under 5 years old

As well as establishing the numbers of visits by schools and EC groups, the survey endeavoured to determine the number of children under 5 years old (not as part of EC centre visits) who had visited art museums and galleries over the past year. This proved impossible as most of the institutions do not count the number of children who visit (apart from those who come to participate in an educator-guided visit), or if they do count children (and only two did) they do not separate them into age bands.

Guided or self-guided?

Self-guided visiting

Self-guided visits involve teachers leading their own tours of an art museums and galleries, facilitating children’s learning experiences without the assistance of the institutions’ educators. Most of the art museums and galleries in the survey reported that EC groups had undertaken self-guided visits to their institution, but as these groups tend not to be counted, exact figures for self-guided visiting over the previous year could not be determined. Nonetheless, it was generally felt by staff that visits by the EC sector were not very frequent.

photograph by Lisa Terreni

One of the directors, who had experienced some EC-centre self-guided visits, felt that they had not been successful, with children sometimes left unattended to wander around the gallery. She strongly argued that EC teachers and their children needed to be well prepared for a self-guided visit. She remarked that this was:

so we can prepare [information] for teachers and be prepared for them! Visits to the gallery should be effective and meaningful, and engage them for days and days afterwards … but just walking off the street may mean they are not going to get the best experiences. We welcome them but they [teachers] need to do some homework and prepare.

This view is supported by research by Carr, Clarkin-Phillips and Paki, which shows that effective teachers who enable children to have art museum and gallery experiences can help children to develop ‘an understanding of the protocols and etiquette associated with art galleries and museums’.[35] Interestingly, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa has fostered an excellent relationship with kindergarten children attending a purpose-built EC centre located in its basement. The EC educator at the museum has developed signage that highlights gallery rules for these children. However, the signs also convey the message to the public that children are welcome in the gallery space. Yet what became obvious from the survey was that resources that specifically assist EC teachers with self-guided visiting are rarely, if ever, available from the institutions.

Two of the educators who participated in the survey said they preferred to work directly with EC groups rather than have the group do a self-guided visit. This was because they felt they had specialist expertise for working with exhibitions – expertise that EC teachers were unlikely to have. All of the 17 institutions had fully equipped and exciting studio/workshop spaces for children. As the art educators also have access to a workshop space, they can provide follow-up art-making activities for children during a visit. This, they felt, was an important aspect to the learning opportunities provided by an art museum or gallery that is unavailable to self-guided groups. This view is also supported in much of the literature about young children’s learning in art museums.[36]

photograph by Lisa Terreni

Guided visiting

As previously mentioned, LEOTC funding was identified by art museum and gallery personnel as the main obstacle to working formally with the EC sector. In most cases it was seen that the programs on offer were inappropriate for the EC sector, although a couple of the educators interviewed were comfortable with being able to adapt their programs to suit younger learners. Nevertheless, it became clear that sometimes EC groups were able to work with educators, particularly if there was a gap in the LEOTC program, if they had an existing relationship with the art museum or gallery educator, or if they were able to negotiate a guided learning opportunity with an educator.

Educational approaches

While questions about educational approaches and pedagogy were not specified in the survey, discussions did highlight aspects of many of the institutions’ educational approaches. As most of the programs offered are geared to the New Zealand primary and secondary school curriculums, learning outcomes and approaches were tailored to these. Strategies described for working with children indicated that a teacher-directed, large-group approach appeared to be the norm. An observation made by the researcher in one of the art museums during the survey revealed that an approach to art-making experiences in the studio involved children decorating identical copies of an adult-developed stylised template. This approach to art-making does not support visual art educational pedagogy and practice in most New Zealand EC contexts.[37] Nonetheless, more research into art museum/gallery pedagogy and practice is needed in order to generate a fuller picture of educational programs and educator approaches.

Educator training was highlighted as an issue at two of the art galleries/museums in the survey. These educators indicated that they were not trained specifically for this age group and, consequently, working with children under 5 years old was problematic for them. However, other educators, also not trained specifically to work with this age group, were very comfortable with working with younger children.

Marketing of exhibitions

All of the art museums and galleries currently market their exhibitions to primary and secondary schools. This is done through email, posted newsletters and/or resource packs. Only three of the 17 institutions marketed their exhibitions and services to the EC sector. One art gallery, however, noted that while it did not market its general exhibitions to that sector it did market the exhibitions considered attractive to the EC age group; for example, the currently travelling Lynley Dodd: A Retrospective exhibition.[38]

Less than half of the institutions (only 6 of the 17) had databases of postal or email addresses for their local EC centres, but two directors identified that they were currently developing these. When asked if this was an area that could be developed, most agreed that it was a good idea, but all said that there was not enough money, time and/or resource people available to do this work. One education manager had simply not thought about targeting this sector, and one educator was a little concerned that if they did advertise to EC centres then the gallery might suddenly be inundated with EC requests for visits which they could not cope with.

Resources for early childhood teachers

None of the art museums or galleries in the survey had information or resources specifically designed to inform EC teachers about how to visit or ways to use the art collections for enhancing young children’s learning. An examination of all of the institutions’ websites revealed that while there were some good teaching resources for primary and secondary school teachers nothing was specifically tailored for the EC sector. However, as several educators pointed out, some of the resources for primary schools could readily be adapted to the EC context. Education resource packs or information sheets often contain good-quality photographs of art works and information about exhibitions that could be useful for EC teachers.[39]

A recent development, a new early childhood blog by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, provides stories about centres that have visited the art collections. It is an innovative approach to informing EC teachers about visiting and giving them program ideas.[40] Nevertheless, developing more resources tailored to the needs of EC teachers is clearly a goal that could be pursued to the benefit of both the EC sector and art galleries/museums. Resources from art galleries in other countries, such as the Smithsonian Institution in the United States,[41] could provide helpful exemplars for this work.

Professional development for teachers

Only a few of the art museums or galleries ran teachers’ evenings to promote their new exhibitions. Owing to a lack of resourcing and repeated low attendance by teachers, this option was no longer seen as a good use of staff or resources by many of the institutions. And even where such evenings were held EC teachers were generally not invited, the rationale being that the events were geared to the learning outcomes in the primary and secondary school curriculums.

Several art galleries/museums did run professional development programs specifically for teachers on how to use the collections to enhance children’s learning, but, once again, EC teachers were typically not invited. A couple of the art educators believed that their hands-on work with children and teachers in the gallery setting also constituted professional development. They felt that during gallery sessions they were able to demonstrate effective teaching practice, and to talk to teachers about ideas for classroom-learning activities. However, as previously noted, the limitations imposed by LEOTC funding mean that this aspect of professional development is, on the most part, not available to EC teachers.

An interesting dimension of the provision of professional development was that four of the institutions regularly worked with students undertaking EC teacher training at their local tertiary training organisations (universities and polytechnics). While these institutions were very willing to work with these students, the irony is that even if students wanted to have a guided visit to an art museum or gallery with children from an EC centre, they may not be able to because of the barriers identified in this paper. Nonetheless, giving EC students the opportunity to become personally more informed and literate in the art gallery/museum context is an important feature of this work, and likely to be of assistance for self-guided visiting with children.

Family services and facilities

Museum and interpretive consultant Graham Black suggests that families are a core audience constituting a significant group of visitors, and that museums need to recognise the clear benefits in reaching out to family groups.[42] He firmly believes that families are also vital to future attendance. Five out of the 17 art museums and galleries had site-specific, permanent art-making and art exploration facilities for families and, in some cases, these could also be used for working with small groups of children from EC centres. However, the intergenerational purpose of the spaces, where all members of a family can work together, was often highlighted by participants in the survey as a priority.

A few art museums and galleries offer family-specific programs. For example, three out of the 17 institutions offer baby-friendly programs for parents accompanied by infants (and sometimes toddlers). These programs were mainly geared to fostering the parents’ experiences of the exhibition, rather than having a child focus, but parents could interact with the children in relation to the works if they chose to. Some, however, specify that these programs are suitable for babies in buggies rather than toddlers. One institution offered a hands-on program for 4-year-olds (attending with their parents or caregivers) where they could create works in the studio workshop in response to their experiences in the gallery. Special arts-focused events and workshops for families throughout the year were also highlighted as ways to increase family and community involvement.

The development of specific exhibitions geared to family engagement and younger audiences was also identified as a way of increasing family participation, and for some art museums and galleries this was an important feature of their programs.[43] One institution described getting children to help select art works for an exhibition as another successful method for encouraging the engagement of children and family groups.

photograph by Lisa Terreni

Discussion

The limitations of LEOTC funding, and the lack of resources and professional development

As previously discussed, government funding through the Ministry of Education’s LEOTC scheme helps to fund most of the art institutions that participated in this survey. The funding enables the organisations to employ art/educators to work with children in the primary and secondary school sectors but not with children from the EC sector. This creates one of the biggest barriers to EC centres using art museum and gallery programs. Those institutions that do not use this funding arrangement to employ educators are often able to accommodate the EC sector much more easily. There are some art educators, however, who are more willing than others to engage with the EC sector and, despite the LEOTC funding restrictions, they are able to work around these to accommodate and work successfully with these groups.

On the basis of the data from this survey, self-guided visiting currently appears to be the best option for the EC sector. This means that EC teachers can determine and facilitate the learning encounters within the art museum or gallery context. However, to be able to do this successfully, EC teachers need to have the requisite skills and experience within this context, to be ‘art gallery literate’ themselves[44] and able to adequately prepare children for visits. As opportunities for art-making responses to the work experienced in the art gallery/museum setting are unavailable when centres self-guide, it is vital that teachers provide follow-up activities back at the centre. Clearly, relevant resources and professional development (of which there is currently very little available to EC teachers) is an area that could be significantly developed.

Family services versus EC centre visits

Family-oriented programs and activity centres for family groups in art museums and galleries are undeniably important for increasing young children’s access to the institutions. It is likely that the families using these facilities will be those with high levels of education and cultural capital in relation to museum visiting and are also more likely to be frequent visitors[45]. Therefore, while it is very important to make provision for family groups, this is neither the only nor even the best means of rendering young children’s visits more equitable. Interestingly, many of the museum and gallery professionals who participated in the survey articulated their desire to make visiting accessible for all schoolchildren; for example, by ensuring access for children from low-decile areas (in one instance, this was taken so seriously by a gallery that it provided free buses), or for those likely to be living in families or communities that lacked the requisite cultural capital to undertake visiting. This supports O’Neill’s argument that it is important that art museums and galleries become socially inclusive and ‘treat all visitors, existing and potential, with equal respect, and provide access appropriate to their background, level of education, ability and life experience’.[46]

However, this level of thinking was, for the most part, not transferred to considerations of the EC sector. The benefits for both children and their parents/caregivers (who often accompany them on excursions) who use EC centres were not recognised and, in some cases, the perception that large groups of children under 5 years of age were likely to ‘run wild’ in the gallery was still current (despite the fact that EC teachers, for the most part, undergo similar teacher training to their primary and secondary counterparts). It is important for art museums and galleries to recognise that 96 per cent of all New Zealand children attend some form of EC service (and, under the current government’s legislation, those in homes receiving social welfare benefits payments must attend some form of EC service in order to qualify for such payments). EC centres are well positioned to offer children experiences in art galleries/museums and other cultural facilities to which they may not have access within their own families. It could be argued that family group visits and facilities are an easier option for art museums and galleries, and that if issues of social inclusion are taken seriously by institutions then greater consideration needs to be given to the support and the provision of programs for children who attend EC centres in New Zealand.

Marketing of exhibitions

While all the art museums and galleries marketed exhibitions and/or programs to the primary and secondary school sector, very few of the art institutions in the survey advertised to the EC sector. This is an area that requires significant development by art museums and galleries; while they may not be able to work directly with EC groups, marketing exhibitions could still be extremely helpful to the sector. With regular marketing information EC teachers would more easily be able to make informed choices about what was on offer, whether the exhibitions connected with children’s current learning interests, whether any related resources could be useful in their program, and whether to schedule and plan for a self-guided visit. Research by Bennett and Frow,[47] which investigated the demographic, cultural and attitudinal characteristics of art gallery visitors to Australian art galleries, suggested that improved marketing can be a means of improving participation by under-represented groups of visitors. The question, however, is whether art museums and galleries in New Zealand genuinely want participation by the EC sector.

Employment of EC trained educators in art galleries/museums

Two of the 17 art galleries/museums surveyed employ EC-trained educators (one employs a full-time educator, the other employs an educator two hours per week) to work specifically with young children. In one of these full-time positions, the educator works not only with EC groups but also across the whole education spectrum. Having a full-time EC position has made a difference to the development of new programs and opportunities for EC groups in these institutions. This view is shared by Kathy Danko-McGhee, a former Director of Education at the Toledo Museum of Art (USA), who believes that ‘thoughtfully planned visits to traditional art museums can be valuable experiences for pre-schoolers’.[48] She strongly believes that her EC background made a significant difference to the programs her museum offered to the EC sector. It is likely, therefore, that the employment of EC-trained personnel can have a positive impact on the nature and provision of programs suitable for the EC sector in New Zealand.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted the barriers to visitor access in art museums and galleries experienced by the EC sector but also, to a lesser degree, some of the things that can be done to facilitate better access for young children. If art museums and galleries are to genuinely rethink their purpose in contemporary Western democratic societies, then it is important to consider the needs, interests and rights of a nation’s youngest citizens[49]. New Zealand and Australian art museums and galleries, like their international counterparts, regularly engage in the debate about improving access and attracting wider and more diverse audiences, and the time is right to expand this debate to consider how to attract and include more pre-school children who attend EC centres.[50]

The intractability of the government’s LEOTC funding in New Zealand is a significant problem in that it automatically excludes the EC sector from education programs run within art museums and galleries. And yet, despite this barrier, there is still the potential for these institutions to develop initiatives that can actively foster the inclusion of young children. Improvements in marketing and the development of teaching and visit-related resources tailored to the EC sector would have a positive impact. Running regular professional development sessions to inform EC teachers about how to use an art museum or gallery effectively with young children could also make a positive contribution to improved access for the sector.

New Zealand is a small nation that has many high-quality art museums and galleries, which showcase the best examples of the nation’s artistic and cultural heritage. If they are willing to forge working relationships with EC centres, then it should be possible to create visiting experiences for young children that ensure successful encounters with visual art and contribute to establishing ‘ deep seated habits of museum visitation as a highly valued activity’ for the rest of their lives.[51]

This article has been independently peer-reviewed.

Endnotes

1 Pierre Bourdieu & Alain Darbel, The Love of Art: European Art Museums and Their Public, Stanford University Press, 1991.

2 Lisa Terreni, ‘Children’s rights as cultural citizens: Examining young children’s access to art museums and galleries in Aotearoa New Zealand’, Australian Art Education, vol. 35, no. 1, 2013, 93–107.

3 Phillip Wright, ‘The quality of visitors’ experiences in art museums’, in Peter Vergo (ed.), The New Museology,Reaktion Books, London, 1989, p. 147.

4 Vergo, The New Museology, p. 3.

5 Max Ross, ‘Interpreting the new museology’, Museum and Society, vol. 2, no. 2, 2004, 84–103; Diedre Stam, ‘The informed muse: The implications of the new museology for museum practice’, in Gerard Corsane (ed.), Heritage, Museums and Galleries: An Introductory Reader, Routledge, London, 2005.

6 Ross, ‘Interpreting the new museology’, p. 100.

7 Maria Xanthoudaki, Les Tickle & Veronica Sekules, Researching Visual Arts Education in Museums and Galleries, Kluwer, The Netherlands, 2003, p. 1.

8 Helene Illeris, ‘Visual events and the friendly eye: Modes of educating vision in new educational settings in Danish art galleries’, Museum and Society,vol. 7, no. 1, 2009, 16–31 (p. 16).

9 See www.museumsaotearoa.org.nz/Site/publications/default.aspx.

10 Conal McCarthy, Museums and Māori: Heritage Professionals, Indigenous Collections, Current Practice, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2011; Conal McCarthy, ‘The rules of (Māori) art: Bourdieu’s cultural sociology and Māori visitors in New Zealand museums’, Journal of Sociology,vol. 49, 2013, no. 2–3, 173–93, (pp. 2–3).

11 Lee Davidson & Pamela Sibley, ‘Audiences at the “new” museum: Visitor commitment, diversity and leisure at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa’, Visitor Studies,vol.14, no. 2, 2011, 176–94.

12 Arapata Hakiwai, ‘The search for legitimacy: Museums in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Māori viewpoint’, in Corsane, Heritage, Museums and Galleries,pp.154–63.

13 McCarthy, Museums and Māori.

14 David Mason & Conal McCarthy, ‘The feeling of exclusion: Young people’s perceptions of art galleries’, Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 21, no. 1, 2006, 20–31.

15 Terreni, ‘Children’s rights as cultural citizens’.

16 As New Zealand is a small country of approximately 4 million people, the 17 art galleries/museums in this survey constitute a high percentage of the total number of art galleries/museums in the country.

17 The PhD research questions include the following: How do art museums and galleries in Aotearoa New Zealand exclude or include young children (attending EC centres)? What are the facilitators and barriers to EC centre access to art museums and galleries in Aotearoa New Zealand? What is the nature of EC centre access to, and use of, art museums in Aotearoa NZ currently? What are the perceptions, practices and conditions that can enable EC teachers and museum art educators to work together to create inclusive and meaningful art learning experiences for young children?

The research uses a mixed-method approach to data gathering, including the art museum/gallery survey, a large national digital online questionnaire to EC centres about excursion destinations, and in-depth teacher interviews and observations with three EC centres (whose use of art museums varies from not using them at all to using them regularly as part of their programs). This research was approved by the Faculty of Education ethics Committee, Victoria University of Wellington (approval number RM 19792).

18 Interestingly, at the same the time that this museum survey was being undertaken, the Wellington Museum’s Trust (WMT) also began carrying out an audit on their responsiveness to certain groups in the community. In conversation with the Head of Strategic Development of the Trust, Sarah Rusholm, she stated, ‘from my point of view we’re currently undertaking an audit and review of WMT provision for children and young people at our institutions … We’ve undertaken quantitative research via Greater Wellington Regional Council’s “Greater Say” online panel, and will be conducting accompanied visits with small groups of children/young people later this month’ (personal communication, Sarah Rusholm, 6 November 2013).

19 See, for instance, Betsy Bowers, ‘A look at early childhood programming in museums’, Journal of Museum Education, vol. 37, no. 1, 2012, 39–48; Angela Eckhoff, ‘The importance of art viewing experiences in early childhood visual arts: The exploration of a master art teacher’s strategies for meaningful early arts experiences’, Early Childhood Education Journal, vol. 35, no. 5, 2008, 463–72; Kathy Danko-McGhee, The Aesthetic Preferences of Young Children, The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, 2000; Karen Knutson, Kevin Crowley, Jennifer Russell & May Ann Steiner, ‘Approaching art education as an ecology: Exploring the role of museums’, Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research in Art Education, vol. 54, no. 4, 2011, 310–22; Andri Savva & Eli Trimis, ‘Responses of young children to contemporary art exhibits: The role of artistic experiences’, International Journal of Education and the Arts, vol. 6, no. 13, 2005, 1–23.

20 For New Zealand, see, for instance, David Bell, ‘Five reasons to take young children to the art gallery and five things to do when you are there’, Australian Art Education, vol. 33, no. 2, 2010, 87–111; Margaret Carr, Jeanette Clarkin-Phillips & Vanessa Paki, Our Place: Being Curious at Te Papa, Teaching and Learning Research Initiative, Wellington, 2012; Esther McNaughton, ‘The language of living: Developing intelligent novices at the Suter Art Gallery’, master’s thesis, Massey University, New Zealand, 2010. For Australia, see, for instance, David Anderson, Barbara Piscitelli, Katrina Weier, Michelle Everett & Collette Tayler, ‘Children’s museum experiences: Identifying powerful mediators of learning’, Curator, vol. 45, no. 3, 2002, 213–31; Barbara Piscitelli & Katrina Weier, Learning With, Through, and About Art: The Role of Social Interactions (in Scott G. Paris, Perspectives on Object-Centered Learning in Museums, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, 2002, pp. 121–51).

21 Carr, Clarkin-Phillips & Paki, Our Place.

22 Lisa Terreni, ‘Young children’s learning in art museums: A review of New Zealand and International literature’, European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, vol. 23, no. 5, 2015, 720–42; David Bell, ‘Five reasons to take young children to the art gallery’.

23 Graham Black, ‘Developing audiences for the 21st century museum’, in Conal McCarthy (ed.) Museum Practice. Vol. 2. The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, Wiley Blackwell, Oxford & Malden MA, 2015.

24 Rosemary Hipkis, Inquiry Learning and Key Competencies: Perfect Match or Problematic Partners?, Te Kete Ipurangi, Wellington, NZ, 2009: http://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/Curriculum-stories/Keynotes-and-presentations/Inquiry-learning-and-key-competencies.-Perfect-match-or-problematic-partners.

25 Ministry of Education, The New Zealand Curriculum, Learning Media, Wellington, NZ, 2007.

26 Ian Bowell, Research Report: Community Engagement Enhances Confidence in Teaching Visual Art,Ako Aotearoa, Wellington, 2012, http://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/download/ng/file/group-3592/community-engagement-enhances-confidence-in-teaching-visual-art.pdf.

27 Ministry of Education, Te Whāriki: Early Childhood Curriculum: He Whāriki Mātauranga mo ngā Mokopuna o Aotearoa, Learning Media, Wellington, 1996.

28 Belonging, Being & Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia,Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations for the Council of Australian Governments, Canberra, 2009.

29 Ministry of Education, The Arts in the New Zealand Curriculum, Learning Media, Wellington, 2000.

30 Closed questions were asked to provide basic statistical data. For example, how many educators do you employ? How many schools have visited? However, despite several questions being closed they often led to a discussion about the topic in question. But more open-ended questions were also asked, to elicit more detailed information. For example, does your museum have information available for EC teachers about ways to use the art museum? If so, what type of information is this?

31 Patricia Bazeley, Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies, Sage, London, 2013.

32 Notes were taken during the interviews that captured the participants’ answers to the survey questions, as well as any comments, thoughts or facts relevant to the discussion. A formal report was written from the notes, and this was sent back to the participants for them to comment on, clarify points that were unclear or needed further information, and add any further comments.

33 For more information, see the LEOTC website, http://eotc.tki.org.nz/LEOTC-home/.

34 Feedback from the EC educator employed at Te Papa indicates that initiatives over the past two financial years have resulted in exceptional increases in visitation from EC groups (educator-led and self-guiding). With 813 children in 2012–13, 3175 children in 2013–14, and 4717 in 2014–15 (with 345 future booked for 2015–16), there is a first-year increase of 290% in visitation, and a second year increase of 49%. Redevelopment of StoryPlace programming, price point and session schedule from July 2013 resulted in a 26% increase in visitation by the end of 2014, even with a 40% reduction in sessions run. In 2015, Matariki program uptake (approx. 1987 children) was almost exclusively from the Early Childhood–Junior Primary sector. Of these approximately 999 were EC children. This is a 78% increase from the first EC Matariki program in 2013, which had approximately 560 participants. The new Matariki education resource, created specifically for EC groups in 2015, had over 25,000 views throughout the country within the first four weeks it was online.

35 Carr, Clarkin-Phillips & Paki, Our Place, p. 6.

36 Angela Eckhoff, ‘The importance of art viewing experiences in early childhood visual arts: The exploration of a master art teacher’s strategies for meaningful early arts experiences’, Early Childhood Education Journal, vol. 35, no. 5, 2008, 463–72; Barbara Piscitelli, ‘Young children’s interactive experiences in museums: Engaged, embodied and empowered learners’, Curator, vol. 44, 2002, 224–29; Savva & Trimis, ‘Responses of young children to contemporary art exhibits’.

37 See, for instance, Felicity McArdle, ‘The arts and staying cool’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, vol. 9, no. 4, 2008, 365–74 or Alex Gunn, Teachers’ Beliefs in Relation to Visual Art Education in Early Childhood Centres, 2000 (retrieved from www.childforum.com/images/stories/2000_Gunn.pdf)

38 Dodd is the New Zealand author and illustrator whose creation ‘Hairy Maclary’, a small and clever terrier, is the hero of a series of children’s picture books; see http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/features/weekend/8947795/Much-loved-scruff.

39 See education resources, for instance, www.artgallery.org.nz/files/artgallery/With%20Bold%20Needle%20and%20Thread%20Teachers%20Pack_0.pdf or http://citygallery.org.nz/assets/New-Site/Education/Education-Resources/Resources-2011/OceaniaTEXTILE-ART.pdf.

40 http://blog.tepapa.govt.nz/category/education/early-childhood-education-education.

41 See, for instance, www.si.edu/seec/resources and www.toledomuseum.org/learn/gallerygear/.

42 Graham Black, Transforming Museums in the 21st Century,Routledge, London, 2012.

43 One example of this type of exhibition is at http://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/exhibitions/blue-planet.

44 Carol Stapp, ‘Defining museum literacy’, Museum Education Roundtable, vol. 9, no. 1, 1984, 3–4; D Vidovic, Museums' Literacy-MusLi, 2010, http://www.fitzcarraldo.it/ricerca/pdf/musli_finalpublication.pdf.

45 Jenny Keate, Know your Audience: A Survey of Performing Art Audiences, Gallery Visitors and Readers, Arts Council of New Zealand, 2000.

46 Mark O’Neill, ‘The good enough visitor’, in Richard Sandell, Museums, Society and Inequality,Routledge, London, 2002, p. 24.

47 Tony Bennett & John Frow, Art Galleries: Who Goes? A Study of Australian Art Galleries, with International Comparisons, Australian Council for the Arts, Australia, 1991.

48 Sharon Shaffer & Kathy Danko-McGhee, Looking at Art with Toddlers, National Art Education Association Advisory, Reston, 2004, p. 2.

49 Lisa Terreni, ‘Children’s rights as cultural’.

50 Black, Transforming Museums in the 21st Century.

51 David Bell, ‘Five reasons to take young children to the art gallery’, p. 92.