Aboriginal Australia

Italian history is punctuated with periods in which there was a flourishing ethnographic interest in other peoples and cultures, inspired perhaps by the voyages of Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus and other explorers.[1] The early 19th to mid-20th centuries saw the amassing of large collections of ethnographic material, including collections of Indigenous Australian objects.[2] In the 1920s and 1930s these collections were often positioned, far away from their cultural context, in cabinets of museums. The 1970s saw a decline in interest and many ethnographic collections were dispersed. Today, however, in Italy and the Vatican, there has been reconsideration of the significance of the collections and they are now regarded as valuable tools for cross-cultural learning. At a time of increased global migration, ethnographic collections have taken on a new importance, offering a bridge to educate the community about non-European peoples and cultures, and so providing an opportunity for cultural understanding. This shift in perception is reflected in the Vatican Ethnological Museum, which implements a policy of community reconnection; in the ‘Diversity is a value’ display in the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology at the University of Florence; and in the Civic Museum of Reggio Emilia, where cultural expression comes alive in the ‘Map for ID’ project.

The most important early examples of European interest in the Pacific are the artefacts collected by James Cook during his exploratory voyages. Cook’s expeditions had considerable influence, for example, on the German academy, especially in the establishment of ethnography as a discipline.[3] Cook’s voyages represent a turning point for Indigenous Australia and the Pacific – he was the first European known to many of those cultures and he brought back to Europe material evidence of those cultures. The number of Cook’s voyages, the volume of ethnographic material that he collected, and the historical vicissitudes experienced by these materials has meant that parts of the ‘Cook collection’ are now found in museums outside Britain. These include collections in Saint Petersburg, Goettingen, Vienna, Bern and Florence.[4]

In the second half of the 19th century, there was a resurgence of interest in Europe in faraway and culturally unique Australia. The arrival of Catholic missionaries, and the subsequent transmittal back to Europe of information and artefacts, helped to raise awareness of Australia’s Indigenous population. The interest stimulated by this exchange led directly to the creation of some of the collections of Aboriginal material in Italy and the Vatican. This paper presents an overview of the history of acquisitions of the main Italian and Vatican collections of Australian material and explains how they got to be there, with reference to some of the key concerns and differences between the institutions and individuals involved.

The Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology at the University of Florence

In the city of the Italian Renaissance, there is a large collection of Indigenous Australian material in the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology at the University of Florence. The original institution was founded in 1775 by the Grand Duke Peter Leopold of Lorraine and consists of a number of museums. The ethnological collection is located in the National Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology, founded by royal decree in 1869. In that year, the first chair of anthropology in Italy was established in what would become the University of Florence. The origin of the collection is to be found, in part, in the so-called Wunderkammer (cabinets of curiosities) that were in vogue during the Renaissance. Funded by the reigning Medici family, the museum’s collection contained objects from the Caribbean, dating from as early as the 16th century. In later years, in addition to African ivory horn and Amazonian bows and arrows, the museum incorporated objects collected by scientific and exploratory expeditions, including from Captain James Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific (1776–79). Objects collected by Cook feature prominently in the museum’s current layout, which features a mask from Nootka on Vancouver Island and a hoe paddle from Aotearoa, New Zealand.[5] The entire collection now comprises 25,000 artefacts from around the world, mostly acquired since the 1870s.

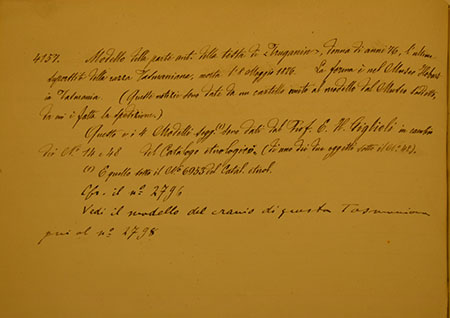

Two significant individuals who increased the ethnographic collection in Florence were the founder of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology, Paolo Mantegazza (1831–1910) and his co-worker and curator, Enrico Hillyer Giglioli (1845–1909). Mantegazza was a prominent Italian neurologist, physiologist and anthropologist, who worked as a doctor in the Argentine Republic, Paraguay and Italy. Noted for his work on the beneficial effects of coca leaves, Mantegazza was an atheist[6] who supported a racial or social Darwinist perspective in anthropology, evident in his Morphological Tree of Human Races (1890). London-born Giglioli was a Florentine zoologist, naturalist, anthropologist, and honorary member of the Royal Geographic Society. He travelled around the world, was part of a scientific voyage to Australia and the Pacific from 1865 to 1868 and wrote about material culture and customs in Oceania. On his return to Italy he catalogued the vast collection at the University of Turin, launching his career as one of the pre-eminent ethnographers of his era. In 1874 he published I Tasmaniani: Cenni storici ed etnologici di un popolo estinto with wood-engraved illustrations, a map and 15 photographic portraits taken from the 1866 Melbourne Exhibition panel of Aboriginal people living at Oyster Cove, including Truganini (or Trugernanner) and William Lanney. In the introduction, Giglioli notes the copies were taken while he was in Sydney in June 1867, with the assistance of the director of the Australian Museum, Gerard Krefft.[7] This 160-page publication was a major monograph on Tasmanians. In 1875 he published Viaggio intorno al Globo (Milan) and in 1911–12, a two-volume publication, La collezione etnografica del Prof. Enrico Hillyer Giglioli, with photographic plates. The first part, on Australasia, includes a descriptive catalogue listing more than 400 implements collected from around Australia, each listed with its original traditional name, description and provenance. Seventy-three different tribal groups are represented.[8] Giglioli’s wife, Costanza Giglioli-Casella, published Intorno al mondo: viaggio da ragazzi in 1891 with a chapter on the east coast of Australia, including a wood-engraved group portrait of three Aboriginal Australians by ‘Medun’. After Giglioli’s death, his collection (except for the objects in Florence) and his extensive archaeological and ethnological library were deposited in the Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Rome.

Australian items donated by Scheidel originate mainly from the Northern Territory and Queensland, with smaller numbers of objects from New South Wales, Western Australia and Victoria. The material on display in two large showcases consists of 39 boomerangs, 23 spear-throwers, 30 clubs, 17 shields, 12 bags and a variety of body ornaments, including armbands, a headband, and necklaces. The collection also includes a breastplate inscribed ‘Wambin, King of Taraganba, Q’,[9] although this is not on display. In the 19th century it was common for museums around the world to exchange objects, which is what happened with museums in Florence, Sydney and Tasmania. Because of various exchanges, it is no longer possible to rely on the Scheidel inventory to accurately itemise the collections, and a more detailed study is required.[10]

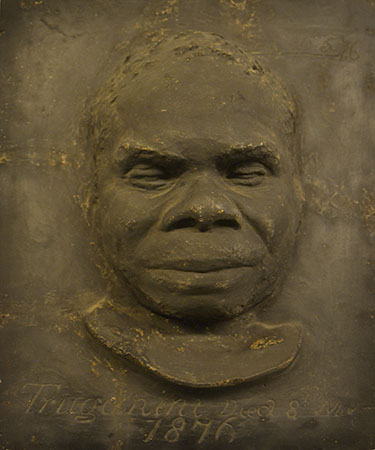

Facial casts or masks

The Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology houses a collection of approximately 600 facial plaster casts. These were used by anthropologists in the mid-19th to early 20th century to study the variation and diversity of humankind based on morphological and morphometric data. Before the development of genetics and molecular biology, some considered facial casts a more efficient technique than photography. German naturalist and ethnographer Otto Finsch (1839–1917), who travelled to Indonesia and Oceania, donated 150 facial casts to the museum, including about 70 masks of Papua New Guinean men.[11]

While in Australia, Giglioli collected five masks of unnamed Tasmanian men from the Tasmanian Museum in Hobart (established by the Royal Society of Tasmania in 1843). There is also a plaster copy of a facial mask of Truganini, made on 10 May 1876, two days after her death. These formed part of an exchange in which two ethnographic objects from Florence were given to the Tasmanian Museum. It was not unusual to exchange objects, and copies of Truganini’s mask were sent around the world.

The facial casts in the museum represent many cultural groupings, including from the Russian Caucasus, Central Asia and Africa. They were originally collected under a racial paradigm of biological determinism popular at the time (which grouped people on an artificial hierarchy using genes or race). They are now being used in an educational display explaining their historical context, the origins of the collection, and techniques that were used in their production. In the display, with the words ‘La diversità è un valore … diverso … come te!’ (Diversity is a value ... different ... just like you!), masks are juxtaposed with photos of people from around the world. There are also mirrors reflecting the viewer’s image back to themselves, inviting them to become a participant in the display. ‘Diversity is a value’ appears in the display in 24 languages.

The Anthropology Museum at the University of Padua

The Anthropology Museum, one of 10 university museums in Padua, not far from Venice in northern Italy, holds a precious historical collection dating back to the 16th century. The museum is closely linked to the university, and many objects, including those related to physics and anthropology, came from the private collections of professors past and present. The collection has expanded over time to include objects related to oriental arts, ethnography, palaeo-ethnology and osteology.

The Museum of Anthropology is home to the most recently acquired Indigenous Australian collection in Italy.[12] The collector was a priest, Don Giuseppe Capra (1873–1952). Originally from the mountainous region of Val d’Aosta, northern Italy, he took vows in the Salesian order of priests. He was a professor of geography at several universities in Rome and Perugia and frequently travelled abroad, primarily to assist Italian immigrants in places including Australia, New Zealand and New Guinea. He was connected to international organisations and worked for the Italian Government. It was during his visit to Australia (between 1908 and 1909) that he had the opportunity to become acquainted with Aboriginal people as well as Italian immigrants and to collect some material evidence of Aboriginal culture, which is now held in the Museum. Don Capra lived and worked with Indigenous peoples and was active in trying to better their conditions. He was sensitive to the inhumane situations he witnessed and was sharply critical of the impact of colonisation: ‘The history of the English occupation is … a stain, a disgrace to the history of civilisation; for the Aborigines, civilisation meant decline, destruction, death’.[13]

The ‘Capra collection’ contains about 40 Australian artefacts, mostly from Queensland and Western Australia, including six shields, four message sticks, five spear-throwers, and some everyday domestic objects. There is little documentation of the collection and no human remains. The artefacts were sent to the Anthropology Museum in Padua between 1928 and 1929. The collection also includes some artefacts from New Guinea and New Zealand. Most of the objects relating to Oceania in the museum, comprising approximately 500 objects from Polynesia and Melanesia (about 300 from New Guinea), come from what is called the ‘Pola’ collection (from the arsenal of the Royal Navy of the Austro-Hungarian Marina of Pola).

Palaeo-ethnology and spiritual life

The first Catholic mass to be celebrated in Australia was in 1788 during the French expedition of La Perouse to Botany Bay. The occasion was the funeral of a Franciscan friar, Louis Receveur. When the First Fleet of the British arrived in Australia in 1788, there were some Catholics among the crew, mostly of Irish origin. The first Catholic priests to take up permanent residence in Australia were convicts: they arrived in 1800, having been accused of complicity in the Irish rebellion of 1789. Catholic institutions were limited in the first 50 years of the colony of Australia.[14]

The collections in the Vatican Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Natural History in Reggio Emilia owe their origins to objects sent by Rosendo Salvado (1814–1900), a Spanish monk who was founder and then abbot of the Benedictine mission at New Norcia in Western Australia.[15] Although both collections come from one source, in each of these museums they took on a different and contrasting role.

The history of the collections of the Museum of Reggio Emilia and the Pigorini Museum in Rome encapsulates the relationship that was established in those early years between Italy and Australia. Interest in the material culture of Aboriginal people was predominantly ‘scientific’, that is, linked to the emerging discipline of palaeo-ethnology and the hope that increased knowledge would contribute to the understanding of human prehistory, or deep history.[16] The collection of the Vatican museums reveals a different approach. The Vatican’s interest was focused on culture and spiritual life; there was no intention of using the material culture as a tool to learn about the distant past of humanity. This was of particular importance, especially in light of the fact that white Australia was at that time a predominantly Protestant country, far removed from the traditional scope of the Catholic Church – for the Church in Rome it was a new horizon.

Rosendo Salvado founded the Benedictine mission of New Norcia, a short distance from Perth in Western Australia, in 1846. In 1846 and in 1852 he sent some Aboriginal artefacts to what was then known as the Borgia Museum of the Propaganda Fide, which merged with the Ethnological Museum of the Vatican Museums at the end of the 1920s. His stated reason for sending these ethnographic materials was to give the Propaganda Fide – and the Pope – an idea of the culture of the Indigenous Australians and the characteristics of the new land in which he and his fellow Benedictines were carrying out their missionary activity.[17]

The second collection, sent by Salvado to Europe in 1871, is held at the Museum of National History in Reggio Emilia, now called the Museum ‘G Chierici’ after the priest who founded it, Don Gaetano Chierici. In this case the initiative came from Don Gaetano, who, after reading Salvado’s book, asked Salvado to send him material because he wanted to use it for his research on human prehistory. This is how the history of the Australian Aboriginal collections is linked to the emergence in Italy of ‘palaeo-ethnology’. It was Chierici who, along with Luigi Pigorini, founded the Italian school of palaeo-ethnology. In the relationship between these two scholars and the collections found in the museums in Reggio Emilia and Rome that bear their names, one can trace a similar history of an interest in Australia that is radically different from that told by the artefacts in the Vatican collection.

Pigorini and Chierici saw significant methodological unity between the study of prehistory and the study of ethnology. Combining the two disciplines gave rise to palaeo-ethnology and to the possibility of putting into practice a method that compared ‘prehistoric’ with ‘primitive’. The similarity of material cultures was interpreted to mean that the cultures themselves were similar. Ethnological artefacts collected from around the world became the interpretive key for understanding the remote prehistoric past of humanity from which nothing written remained, so ethnologists were interested in studying the tools and utensils still in use in various parts of the world. The study of ‘pre-history’ can be seen as Europeans trying to understand their past through selected cultural objects they can relate to and access in their present. Less well preserved, though, are the often intangible remnants of spiritual or religious practice, or the knowledge to interpret such cosmological systems. The aim of palaeo-ethnology was ambitious: to reveal something about the social organisation, the culture and the religion of Europe’s remote ancestors. How to make the stones speak? How to deduce the religion of prehistoric peoples from a prehistoric tool?[18]

It is here that the comparative method based on the theory of evolution comes to the fore.[19] Darwin and his followers proposed that there is a common human nature and a common historical course of evolutionary development through the races. Following from this, it was supposed that human beings were similar everywhere – there is no difference between an Aboriginal person and an Italian, for example. And wherever humans may be, their history follows the same evolutionary stages.[20] This constructed linear timeline assumed there was a time when the Italian was on the same level in terms of material culture as the Aboriginal person, and that the Aboriginal person would one day be at the level of the Italian. The palaeo-ethnologists especially argued that this could be proven by the similarity of artefacts. The prehistoric arrowhead that Chierici and Pigorini found in their excavations in the Apennines in northern Italy was similar to that of the Australian Aboriginal sent to Italy by Salvado. The prehistoric inhabitants of the Apennines have disappeared, but not Aboriginal people. Therefore, by studying Aboriginal people – their culture, religion and social organisation – one could also come to an understanding of European prehistory.[21] There was no way they could have known at the time that Australian Aboriginal culture had sustained itself continuously for at least 50,000 years.

Through this dominant positioning, tribal groups were referred to as ‘primitives’ and no distinction was made between ‘primitive’ and ‘prehistoric’. Indeed, based on the equation primitive = prehistoric, the thinkers of the day saw importance in gathering as much information as possible about the ‘primitives’ (tribal groups) before they ‘disappeared’. It is no coincidence, then, that Pigorini’s museum was called a ‘prehistoric’ and an ‘ethnographic’ museum, and it is for this same reason that both Pigorini and Chierici were interested in Australian artefacts (Chierici more so than Pigorini, who entrusted this task to his assistants).

It was Darwin’s second voyage on HMS Beagle (1831–36) that took him to Australia via the southernmost inhabited tip of Cape Horn, where he formulated his theory that civilisation had evolved over time. Observing the canoe nomads, he said of the Yahgan people, ‘I never saw more miserable creatures’,[22] a statement he would later come to regret. Ironically, he had missed the point that the Yahgan, who lived with a rich ceremonial life (Darwin recorded their facial and ceremonial body ochre), in sub-zero temperatures, had adapted perfectly over 10,000 years or so to their specific environment.[23]

At a later stage, some palaeo-ethnologists combined diffusionist theories with this evolutionary substratum. For them the independent origin of an object – for example, a similarly shaped bow in two distinct far-off regions of the world – was not to be explained simply as the result of the independent evolution of a common human nature, but rather was evidence of the spread of an object or an idea through migration or some other means.[24] This line of inquiry was developed at the Ethnological Museum of the Vatican, founded on the theories of Father Schmidt, who worked on a theory of primitive monotheism (discussed below).

The G Chierici Museum in Reggio Emilia

In northern Italy, the G Chierici Museum of Palaeontology in the Civic Museums of Reggio Emilia was formed by the fusion of two institutions, built in different epochs. The Natural History Room, comprising the scientific collection of Lazzaro Spallanzani, was acquired by the city after his death in 1799. The Storia Patria Museum (National History Museum) was founded by Chierici in 1862, when Italian unification generated an enthusiasm for regional museums.

The Spallanzani collection is still on display in the Chierici Museum and represents the first kind of museum. The Chierici Museum marks the passage from the 18th-century Wunderkammer to a ‘scientific collection’ and preserves the Wunderkammer as well as encompassing more modern displays. The museum remains a remarkable example of this transition before collection history changed and museums were re-organised into categories we see today. In the Wunderkammer, strange animals can be seen, with parts fused together to create a fish-tailed monkey, for example.

Born in the province of Reggio Emilia, the priest Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729–1799) was a professor of logic, metaphysics and Greek, a biologist and a physiologist, who made important contributions to the study of bodily functions.[25] He was one of the first to conduct experiments on the workings of the stomach, and was known to experiment on his own stomach. He discovered that gastric juices were part of a chemical process in digestion.[26] He was also the first to perform in-vitro fertilisation, with frogs, and artificial insemination, using a dog. Widely travelled, with close relationships to scholars and philosophers, he was a controversial figure.

Another priest, Gaetano Chierici (1819–1886), archaeologist and teacher of mathematics, was, like Spallanzani, born in Reggio Emilia, and travelled extensively throughout Italy. Ordained in 1842, he was also active in politics. With a strong yet critical faith, he held liberal ideas, particularly about the need for the Pope to give up his temporal power, though he abandoned his political stance in 1866. As early as 1863 he became interested in palaeo-ethnology and, in 1875, founded the Bullettino di paletnologia italiana, a periodical that was published in Italy for more than 50 years (1875–1931), and which produced 207 editions.[27]

In the first issue, mention was made of the Australian material that Salvado had sent some years earlier, the importance of which Chierici explained in a letter to the mayor of Reggio Emilia on 22 July 1871:

The objects are few and simple, but all the more valuable for science, which detects in them a human being still living at the lowest level of civilisation, if that is what it can be called. We refer to it as the First Stone Age because of the use of rough stones rather than metals to shape weapons and tools, since metals were still unknown. By means of comparison we can ascertain and explain a similar period of ancient history, one that has left traces even in Italy, and in this province no less than elsewhere.[28]

Evident here is the comparative method then in vogue, which held that similarities between material cultures pointed to a broader cultural similarity. Anna Bartolini, retired curator of Oceania and Australia, confirms that Chierici, in an article published in 1875 in the Bullettino, made use of some Australian objects to support his ‘evolutionist’ theories.[29] One of the first collections that Chierici brought to the museum was material from the Sioux Native Americans that had been gathered in 1844.[30] His intention, through a synthesis of the history of man, was to give precedence to the ethnographic aspects before the archaeology – to simultaneously compare and explain the ancient area of Reggio Emilia and other areas throughout the world. He used cultural objects to support his proposed order for the history of humanity that moved from pre-writing to writing. The Chierici Museum depicts this constructed theory moving from Aboriginal Australian, to Native Americans (Sioux pictogram), to African, Chinese and, finally, Egyptians.[31]

We can assume the 31 Australian objects in the Chierici collection came from around New Norcia, but their exact provenance is not known. The importance of the collection is in its representative depiction of objects in daily use and items needed for survival, including tools, weapons and stones used for healing. Chierici was distressed to find that some of the items sent from Perth by Salvado, especially those made out of kangaroo skin, had been damaged during delays in transit. He drew up the following list of items (translated from Italian):

3 long spears (ghici)

3 similar short ones (jauac)

1 spike used as a lance (wana)

2 special gadgets used to throw the ghici, in place of a bow, which is unknown to those tribes (miro)

4 defence shields (unda)[32]

2 gadgets to throw when hunting birds [the boomerangs were noted as not returning]

1 stone hammer-axe (coccio)

1 knife made of shards of glass, which replaced flint after glass was introduced by the Europeans (dabba)

4 bone bodkins to serve as awl, chisel and needle

4 sea shells (molluscs) used as bowls

2 stones of the kind used by the boglia (doctors), who pretend to remove them from the bodies of sick people

1 pouch of kangaroo skin, 1 kangaroo hide, 3 opossum hides – severely damaged by moths – [these could be spotted quoll, not opossum]

Kangaroo and opossum teeth

Kangaroo nerves used to bind and sew

Pieces of pitch and Xanthorrhoea resin used as glue, chewing gum, and material used for body painting

3 pieces of mineral – lead, copper and iron – which shows the lack, not of minerals in those parts, but of the art of fusing them into useable objects.[33]

According to Bartolini, Salvado’s Memorie storiche dell’Australia (Historical Records of Australia), published in Rome in 1851,[34] aroused Chierici’s interest in Aboriginal people and led him to request artefacts from Salvado that would illustrate their way of life. The third part of the book describes social organisation, costumes, ornaments, body painting, dances, habits and people’s movement over the land. It also reveals a deep knowledge of objects and their uses, including the hunting and skinning of animals. The collection in the museum corresponds to the time of the book’s publication. Bartolini notes that in his description, Salvado sometimes allows himself to wax poetic in wonder as, for example, when he speaks of people setting fire to one end of the boomerang before throwing it when they hunt at night: ‘What a beautiful sight it is, this bright spot in the sky wrapping itself in thousands of small circles and bursts of sparks’.[35] But the main reason Salvado’s description is so valuable from a European perspective, is that he explains the social structure of the local people, the distinction of roles between men and women, and the importance of certain items. For example, Salvado specifies that, when travelling, it was the man who carried the weapons:

In his hands [he held] the ghici (javelin), the miro (launcher), the unda (shield); on a band of possum wool that encircled his hips hung the dauac (short spear), the calé (boomerang), and in the rear, the coccio (hatchet-hammer), with the handle positioned between his buttocks so as not to be a hindrance to him on his journey.[36]

Meanwhile the woman followed the man:

carrying on her back and tied to her neck the culto (kangaroo leather pouch) containing a supply of Xanthorrhoea rubber, stones for the hammers, ghici, knives, used to pound the barks of trees, the boglia stones, acacia gum, kangaroo nerves, different coloured clay or chalk [ochre] for drawing, some pieces of concave wood for drinking, possum wool, string and feathers of various birds, untanned kangaroo skins, ointment, provisions of roots and edible bark, kangaroo teeth, and one or two bone ornaments for the nose.[37]

Salvado’s descriptions, along with the items he sent to Reggio Emilia, thus provided Chierici with the material he needed to apply the comparative method and demonstrate the validity of his theoretical assumption, that palaeo-ethnology could help in understanding humanity’s remote past. Indigenous Australians were especially important since their material culture represented an essentially pre-contact civilisation.[38]

Today the rich collections from the remote and recent past in Reggio Emilia have been utilised in a ‘Map for ID’ project, in which the museum has partnered with the government Istituto per i beni artistici culturali e naturali (IBC). The initiative reflects the value placed on intercultural dialogue that Italy now assigns to ethnographic collections. The project encourages museums to be centres for discussion and dialogue, accommodating different visions and viewpoints that reflect the complexity of contemporary society in fast-growing multicultural centres in northern Italy. An example of this is the three-part video, Mothers, which intersperses images of Mother, Goddess or Madonna statues and representations from ancient times and cultures, with interviews of women from those different cultural backgrounds living in Italy today.[39]

The Pigorini Museum in Rome

The history of the Australian Aboriginal collection of the Pigorini Museum in Rome, the most important ethnological museum in Italy, is similar to that of the Museum of Reggio Emilia, though its collection has a different provenance.

Along with Don Gaetano Chierici, Luigi Pigorini (1842–1925) was the founder of Italian palaeo-ethnology. He was the first director of the Museum of Parma, not far from Reggio Emilia, where Chierici worked. In 1870 Pigorini became the director-general of the museums and excavations of antiquities in Rome. In 1876 he founded a prehistoric–ethnographic museum in Rome, to which his name would be given. He was professor of palaeo-ethnology at the University of Rome, where, over the course of 40 years, he formed a group of followers. Among them was Giuseppe Angelo Colini (1857–1918), who began as a clerk at Pigorini’s prehistoric–ethnographic museum and then became a superintendent of the antiquities of Rome and neighbouring provinces. Colini wrote the first description of the objects sent by Salvado to the Vatican, now preserved in the Vatican Ethnological Museum. The history of the Pigorini Museum, like that of the Vatican Ethnological Museum, is rooted in the work of ecclesiastics who were interested in the cultural expressions of peoples outside Europe. In the case of the Vatican Ethnological Museum, this figure was Cardinal Stefano Borgia (1731–1804), a passionate collector, whose personal museum was the talk of travellers and writers of the time and became a ‘must see’ for visitors taking the grand tour. It was admired by German poet Goethe, who wrote of ‘such a treasure, a stone’s throw from Rome’.[40] After Borgia’s death in 1804, his collection became the Borgia Museum (Museo Borgiano) of Propaganda Fide, where the collection was housed until 1925 when it became part of the Vatican’s Ethnological Museum. For the Pigorini Museum it was the 17th-century German Jesuit Father Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), a scholar and polymath who published some 40 major works, in fields like Oriental studies, Egyptology, geology and medicine. A Renaissance man, he was ‘a champion of wonder, a man of awe-inspiring erudition and inventiveness’. His work was read ‘by the smartest minds of the time’.[41] In fact, the nucleus of the Pigorini Museum consists of the ethnographic collection from Kircher’s Roman College Museum.

From 1876, the collection of the Pigorini Museum was enriched by donations of Italian researchers and explorers, such as Enrico H Giglioli (more than 17,000 pieces collected on the voyage of the Magenta between 1865 and 1868) and the Genoese captain Luigi M D’Albertis, whose collection relating to Oceania became part of the museum in 1882. Another collection relating to Oceania (and Borneo), that of Ottavio Beccai, came to the museum between 1880 and 1890, followed by the collection of the explorer Lamberto Laria, comprising mainly materials from the Melanesian islands, in 1891. The Pigorini Museum holds the largest collection of Australian material in Italy, about 800 objects.[42] These include objects collected by arguably the most inflential collectors of Australian ethnographic material, Walter Baldwin Spencer and Francis James Gillen. The Pigorini’s Spencer and Gillen collection was obtained by Giglioli himself, directly from Spencer. As well as the above-mentioned collectors, Australian objects came via FM Thompson.[43]

In the only catalogue of the museum, compiled by author and curator Carla Rocchi and published in 1976, the presentation of the Australian collection opens with these words: ‘Australian culture, as it presented itself to the first whites who came into contact with it, and which survives to this day in the groups that have not been acculturated, is, in certain respects, at the level of the Stone Age’.[44] A century after the founding of the museum, the evolutionary theories on which the Pigorini Museum was founded continued to be invoked. Rocchi claims in the catalogue that Aboriginal people are of Asian origin, and the specific characteristics of their culture are attributed to the long period of isolation after their arrival in Australia. The author contrasts the sparsity of the material culture of Indigenous Australians – which are attributed to a poor and hostile natural environment – to the richness of their social structure, based on totemism, and spiritual life, based on a belief in semi-divine cultural heroes who in a mythical era crisscrossed the earth and created the culture and the natural environment in which Aboriginal people still live. The importance of these cultural heroes, of the stories that portray them and of the rituals associated with them is that they shape not only the religious and spiritual life of Aboriginal people, but also music, dance, and especially their graphic arts, which constitute the most widely known and impressive artistic creation of Australia.[45]

The Australian artefacts in the museum were mainly collected during the second half of the 19th century. The catalogue makes no mention of exact dates or artists. Among the various art forms, Rocchi emphasises both sculpture, with reference to carved poles, and bark painting. The most interesting of these paintings, known as ‘X-ray’ paintings, show not only the exterior but also, on a practical level, the insides of animals – revealing important knowledge of how to prepare the animal for food and the position of internal organs. One polychrome painting on bark in the Pigorini Museum depicts a part of the myth of the Wawilak sisters, who are eaten by the snake Julunnggul;[46] others in the same style show animals such as the emu and the goanna lizard. From the Arnhem Land region there are also paintings of mimi spirits on bark, which, like the wandjina creator beings discussed below, have no mouth.[47] Other significant objects are a mother-of-pearl pendant, a boomerang from Dampier Land, Western Australia; and launchers and a 107-centimetre shield from Queensland.[48] Of particular interest among the more recent creations – included in the catalogue perhaps to demonstrate cultural adaptation – is a dance mask made from a gasoline can, one side of which has been painted.[49]

The Vatican Ethnological Museum

Father Wilhelm Schmidt (1868–1954), Austrian linguist and an authority on ethnography and the history of religion, was the founder and intellectual force behind the Vienna School of Ethnology.[50] He organised the Universal 1925 Vatican Exhibition, from which was born the ethnological department of the Vatican Museums in the following year. For the 1925 exhibition, 100,000 objects were sent from around the world. It lasted a year, then 60,000 objects were returned to the communities they came from and the 40,000 that remained became the core collection of the Vatican Ethnological Museum.

From 1927 to 1939 Schmidt served as first director of the Vatican Ethnological Museum. His monumental 12-volume work Der Ursprung der Gottesidee(The Origin of the Idea of God) was published between 1912 and 1954. He published extensive studies of Indigenous Australian languages,[51] and focused on specific ethnological themes, paying special attention to the cultural and social expression of religion and spirituality. He developed a theory of primitive monotheism or ‘Urmonotheismus’ – which, as mentioned above, challenged the evolutionary view. He believed the more seemingly ancient a group, the closer it might be to the original revelation of God; the simpler the material culture, the ‘truer’ the spiritual world of a group. Traces of the original message of God, therefore, could be found, according to Schmidt, in the contemporary groups of people who were known at the time as Pygmy, San Bushmen, Aboriginal Australians and other groups of hunter–gatherer–fisher peoples like the Yahgan of Tierra del Fuego, Chile. The original message, now lost, in what was seen as subsequent degenerations like polytheism and animism, could be rediscovered by studying these cultures in depth. Pope John Paul II echoed this concept in 1986 in his Alice Springs address to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples when he said they still hold the original understanding of God: ‘You did not spoil the land, use it up, exhaust it, and then walk away from it. You realised that your land was related to the source of life’.[52]

Eminent ethnologist Father Martin Gusinde (1886–1969), who belonged to the same Catholic missionary order as Schmidt, the Societas Verbi Divini (SVD), or Missionary Society of the Divine Word, founded in 1875 in the Austrian Tyrol, was one of the museum’s early collaborators. He made four journeys to Tierra del Fuego between 1918 and 1924 for ethnological research among the Selknam, the Alakaluf and the Yahgan peoples. Gusinde was allowed to take part in and record the Yahgan ceremonies and, according to some sources, he was initiated into one of these groups during the second journey. The Yahgan people today are using Gusinde’s published research, including three large works translated into Spanish, for their family history and cultural and ceremonial revival. For example, they are drawing on his documentation of the meanings of facial and body decorations and the associated ceremonies. The southernmost museum on earth, Museo Antropológico Martín Gusinde in Puerto Williams, bears his name.

The Vatican Ethnological Museum showcased its Australian collection with an exhibition in 2010 called Rituals of Life: The Spirituality and Culture of Aboriginal Australians through the Vatican Museums Collection. There are about 300 objects that make up the collection and these date mainly from the mid-19th to the beginning of the 20th century. The major areas of provenance are the Tiwi Islands in the Northern Territory, New Norcia in southern Western Australia, and Kalumburu in the north Kimberley region of Western Australia, which was established by the Benedictine monks from New Norcia in 1908. There are also some rare objects from other parts of Australia. The most ancient nucleus of the collection is made up of about 30 artefacts, mainly tools of everyday life sent by the Benedictine monks of New Norcia some time between 1852 and 1885 to Propaganda Fide’s Borgia Museum in Rome, and then incorporated into the Ethnological Museum in the late 1920s. There are no human remains in the collection. Father Perez gives an example of the extent of exchange that was occurring at the beginning of the settlement of Kalumburu, when local people were utilising the settlement for food and medicine:

Presents of native artefacts poured in, in sufficient quantities to stack a museum; fire-sticks (kun-an), walos, pagos, spear heads, yomel and spears, hair girdles, turtle shells and the like, all of which were later sent to the mother house for shipment to the Ethnological Museum in Rome.[53]

Interest in the cultural and spiritual expressions of peoples outside Europe, promoted by Cardinal Stefano Borgia (1731–1804), is evident in the collection. The main cultural objects on display include 10 delicately preserved pukumani funeral poles from the beginning of the 20th century from the Tiwi Islands; a series of 13 double-sided paintings on slate, named Wandjina Song Cycle for the exhibition by the artist, Miuron, a Qwini/Kalari man, with some images by Brandibram, painted in about 1917 at Kalumburu, and a double-sided wandjina creator-being painted on bark from the Munja settlement in the Walcott Inlet area of northern Western Australia, and dating from about 1920. This is an early example of the transposition onto a portable surface of a technique performed for tens of thousands of years on rocks in the landscape. It is assumed that Wandjina Song Cycle was painted to communicate local cosmology to a European audience. As objects of art, these paintings also represent a visual diary of an early period of encounter in Australian history.

Another aspect of history is revealed through Pallottine priest Father Ernest Worms (1891–1963), who worked in the Kimberley region and in south-eastern Australia.[54] He sent stone chip fragments to the museum in 1945 from Phillip Island in Victoria. His accompanying letter identifies the fragments as being ‘from the extinct tribe of the Bunderon’. In an interview in 2013, Aunty Carolyn Briggs, director of the Boon Wurrung Foundation in Melbourne, confirmed that the Boon Wurrung (Bunderon) people living on Phillip Island, where Worms had collected the stone chips, had been wiped out prior to contact because of tribal conflicts over women.[55] However, they survived elsewhere as a people and remain a thriving community in Melbourne and other parts of Victoria today.

The Vatican Ethnological Museum’s recent efforts have been to highlight world cultures through special exhibitions in the museum and externally, featuring artefacts that show the diversity of human expression manifest through objects of belief or material representations of spirituality. Examples of collaborations include Portamisal de Cristóbal Colón in Cuba 2012–13, Objects of Belief at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in 2013, Ode to the West and East Small Gates in Korea in 2014, and So That You Might Know Each Other: The World of Islam from North Africa to China and Beyond from the Collections of the Vatican Ethnological Museum, shown in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, in 2014. Under the new direction of Professor Fr Mapelli, a priority has been to use the objects for community reconnection; visitors to the Vatican Ethnological Museum can learn about the heritage of contemporary cultures today through artefacts on display, multimedia, photographs and direct quotations by (where possible) descendants of the artists who originally made the objects. This is especially the case in The Ethnological Museum: History, Mystery and Treasures (2012) and Tecumseh, Keokuk, Black Hawk. Portrayals of Native Americans in Times of Treaties (2013).[56]

Conclusion

In the context of other histories of collecting, this study of the distributed collection of Australian material in Italy and the Vatican makes a contribution to the history of ideas about collecting and collections by revealing not only the story behind the collections but also the motivation of the collectors, curators and society of the time. As well as informing a European audience about Australia, these collections have contributed to Europeans understanding themselves.[57] Indigenous Australian collections in 19th-century Italian cultural institutions informed European science and an interest in spiritual expressions outside Europe.

Again today, there is a growing interest in other cultures as a way to understand a quickly changing world, and the ethnographic collections, as a rich educational resource for intercultural dialogue, have a role to play that is of local and global significance. With greater cultural understanding of ‘the other’, ethnographic collections can offer alternative ways of seeing the world with renewed respect and appreciation. Even as the traditional role of museums adjusts to reflect deep social changes, they continue to be emblematic spaces, representing the consolidating values and identities of societies. The positioning of Indigenous Australians in the collections has shifted from Indigenous objects to subjects. Discussions about cultural redress in the ongoing management, care, restoration and conservation of Indigenous collection items have been an important area of development in museology. Indigenous-focused museum practice is underpinned by daily work with cultural protocols, customs and beliefs that actively recognises the spiritual and cultural connections all communities have to their collections.[58] This is influencing museum practice worldwide with broader projects that incorporate cultural, historic, traditional and spiritual considerations.

The connections made through collectors and Catholic missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries reveal another aspect of the European matrix of Australia’s contact history. A study of the context of the collectors and the intellectual world they came from also reveals by contrast the distinct self-sufficient existence of Indigenous Australians. The artefacts collected have now outlived their collectors, and ‘everyday objects’ have become treasured cultural objects of the past as well as ambassadors for future creative engagement, building new associations and ‘networks of meaning’.[59]

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

Endnotes

1 This research was co-sponsored by the Australian Academy of the Humanities, partnered with the Italian Accademia Nazionale Dei Lincei. Their contribution allowed me to travel and study in Italy in October–November 2012. I want to give special thanks to the institutions and the museum curators of Florence, Reggio Emilia, Padua, Rome and the Vatican City for their ongoing assistance and enthusiastic help. I would particularly like to thank Dr Christina Parolin, Christine Barnicoat and Jorge Salavert, the Australian Academy of the Humanities, Australia; Dr Marco Zeppa and Pina Moliterno, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Italy; Professor Fr Nicola Mapelli, Vatican Ethnological Museum; Dr Monica Zavattaro, Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology, University of Florence; Professor Roberto Macellari, Dr Anna Bartolini and Dr Georgia Cantoni, Reggio Emilia Civic Museums; Dr Nicola Carrara, Museum of Anthropology at the University of Padova; Dr Luigi La Rocca, Pigorini Museum in Rome.

2 The term ‘Indigenous’ encompasses Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. Sometimes the word ‘Aboriginal’ is used, as it was at the time, to refer to collections that are predominantly from mainland Australia. Specific group identities are preferable and used where possible: for example, the Tiwi people of Melville Island.

3 D Heintze, in A Kaeppler and R Fleck (eds), James Cook and the Exploration of the Pacific, Thames & Hudson, London, 2009, pp. 64–5.

4 See, for instance, A Kaeppler (ed.), Cook Voyage Artifacts in Leningrad, Berne and Florence Museums, Berenice P Bishop Museum Special Publication 66, Honolulu, 1978; M Hetherington & H Morphy (eds) Discovering Cook’s Collections, National Museum of Australia Press, Canberra, 2009.

5 In 2009 the Museum of Florence loaned objects from the Cook collection to the travelling exhibition James Cook and the Exploration of the Pacific, held in Bonn (Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland), Vienna (Kunsthistorisches Museum mit Museum für Volkerkunde) and Bern (Historisches Museum Bern Abteilung Ethnographie), and a catalogue was produced for this occasion.

6 Paolo Mantegazza, Ricordi politici di un fantaccino del Parlamento, Bemporad, 1896, p. 72.

7 EH Giglioli, I Tasmaniani: cenni storici ed etnologici di un popolo estinto, Fratelli Treves, Milano, 1874.

8 EH Giglioli, La collezione etnografica del Prof. Enrico Hillyer Giglioli, Coi tipi della Società tipografica editrice, Città di Castello [Italy], 1911–12.

9 C Cooper, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections in Overseas Museums, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1989, p. 66. Cooper’s report provides detailed object lists of some of the collections mentioned in this paper.

10 Cooper’s 1989 report notes that 75 duplicate specimens from the Spencer and Gillen collection were acquired from the National Museum of Victoria.

11 Finsch published his work in 1888 as Masks of Faces of Races of Men from the South Sea Islands and the Malay Archipelago Taken from Living Originals in the Years 1879–82.

12 At the time of writing, the museum was in a temporary space and objects relating to Australia were in storage. Images of and information about some of the Indigenous Australian artefacts can be seen on their website, www.musei.unipd.it.

13 Museo di Antropologia, www.musei.unipd.it/antropologia/approfondimenti/oceania.html, accessed 16 August 2012. See also Studi Emigrazione/Migration Studies, vol. xlviii, no. 183, 2011.

14 This was due to hostilities between Roman Catholics and Protestants that had been imported from England, and the legal disadvantage of Catholic and Irish people within the British Empire. The Church Act of 1836 established legal equality for Anglicans, Catholics, Presbyterians and, later, Methodists.

15 Linguist and the first Australian Roman Catholic abbot, Salvado spent a year living in the open and travelling with the local people to learn their language and customs, but found he learnt more around the fire than in the hours walking or hunting, so decided to build a mission where ‘hospitality could be given to all the natives who wanted to learn a trade or receive religious instruction … [without] the hardships of the nomadic life’ (R Salvado, The Salvado Memoirs, ed. & trans. by EJ Storman, Benedictine community of New Norcia, 2007, p. 54). He played a piano concert in Perth to raise funds for the New Norcia monastery. Salvado made several trips to Europe, took part in the First Vatican Council of 1869–71, sailed on his final trip to Europe in 1899 and died in Rome in 1900. In 1903 he was reburied in New Norcia.

16 For reference on palaeo-ethnology in Italy, see G Pinza, ‘Etnologia e paleoetnografia’, in Rivista internazionale di scienze sociali e discipline ausiliari, vol. 38, no. 152, 1905, 556–59; A De Francesco, The Antiquity of the Italian Nation: The Cultural Origins of a Political Myth in Modern Italy, 1796–1943, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013.

17 While in Europe waiting permission to return to Australia, he wrote and published Memorie storiche dell’ Australia particolarmente della Missione Benedettina di Nuova Norcia, Tipografia Priggiobba, Napoli, 1851 (published in Italian, Spanish and French, and then in English in 1977); R Salvado, Relazione della Missione Benedettina di Nuova Norcia nell’Australia Occidentale (1844–1883) del 1883, in Archivio Propaganda Fide, SC Oceania, Misc. 1, Città del Vaticano; G Cipollone & C Orlandi, Aborigeno con gli Aborigeni: Per l’evangelizzazione dell’Australia, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, Città del Vaticano, 2011.

18 French and German researchers were also active in studying the development of humans. In Britain William Dugdale considered the significance of stone tools as arms (1656), and Edward Lhwyd (1660–1709), Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, wrote in 1699 about ancient arrowheads, comparing them with arrowheads made by American Indians. See J Cook, ‘The discovery of British antiquity’, in K Sloan & A Burnett (eds), Enlightenment: Discovering the World in the Eighteenth Century, British Museum Press, London, 2003, pp. 178–91.

19 Popularised by English anthropologist EB Tylor (1832–1917) in his book, Primitive Culture (JP Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1871).

20 In the 19th century, the hotly debated theories of human origins along the lines of monogenism and polygenism were integral to early conceptions of ethnology.

21 Chierici and Luigi Pigorini were important figures for their study of prehistory, and both worked in the Terremare, a habitation site in the Po valley, northern Italy dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Age, about 1700–1150 BC.

22 ‘… stunted in their growth, their hideous faces bedaubed with white paint and quite naked… their red skins filthy and greasy, their hair entangled, their voices discordant, their gesticulation violent … Viewing such men, one can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow creatures placed in the same world’. C Darwin, in RD Keynes (ed.), Charles Darwin’s Beagle Diary, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001, p. 222.

23 The women dived into freezing waters yearlong for mussels and gave birth underwater (Christina Calderon (known as the last Yahgan speaker), pers. comm. 2012). People kept warm with fires and the animal fat that covered their naked bodies was used for its insulating properties.

24 See also the work of Australian–British anatomist Sir Grafton Elliot Smith.

25 Educated at a Jesuit college, he began studying law then switched to science, a move attributed to the influence of professor of physics Laura Bassi (Bologna 1711–1778), the first woman to teach at a university in Europe, who herself was encouraged by Cardinal Prospero Lambertini, who later became Pope Benedict XIV (‘Laura Bassi’, Encyclopedia of World Biography, http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Laura_Bassi.aspx, accessed 13 December 2012).

26 L Spallanzani, Dissertationi di fisica animale e vegetale, 2 vols, 1780.

27 Biblioteca di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte (BiASA), Periodici Italiani Digitalizzati,

http://periodici.librari.beniculturali.it/PeriodicoScheda.aspx?id_testata=15.

28 Chierici, letter to the mayor of Reggio, 22 July 1871, cited in Bartolini, ‘Armi e strumenti degli Aborigeni Australiani, p. 1. The English version was translated through New Norcia.

29 See G Chierici, ‘Le selci romboidali’, in Bullettino di paletnologia Italiana, Anno I, no. 1, 1875.

30 Collected by Antonio Spagini, a revolutionary who escaped pre-unified Italy and had a tobacco store in America, where he collected the cultural artefacts.

31 In line with contemporary museum practice relating to engagement, Roberto Macellari, the current director of the museum, organised Dakota Sioux representatives to come to the museum to see the collection. An elaborate ceremony was arranged at which Bartolini remembers the peace pipe, a very high symbol of religiosity, being brought out. Before the ceremony could take place however, the peace pipe needed to be separated, to show it was not in active use, which took some days, before the ceremony could take place (pers. comm., 31 October 2012).

32 Only three shields remain, one having been sent to Palma and then lost following its return to Reggio Emilia after the dismantling of the Palma anthropological collection.

33 A Bartolini, ‘Armi e strumenti degli Aborigeni Australiani nel Museo “G Chierici” di Paletnologia: La donazione di Monsignor Rudesinde Salvado della Abbazia di Nuova Norcia (Australia) 1971’, in Pagine d’archeologia, no. 3, 2000–2002, Reggio Emilia Musei Civici. An English version was made available through New Norcia.

34 Reprinted in Naples in 1852, it was published in Italian, Spanish and French, and English in 1977.

35 Salvado, Memorie storiche dell’Australia, 309–10 (in Bartolini, ‘Armi e strumenti degli Aborigeni Australiani’ (pp. 4–5)).

36 ibid. (p. 5).

37 ibid. (pp. 5–6).

38 The Aboriginal Australian collection travelled once, to be part of the 2007 exhibition in Trento, Scimmia Nuda, Storia dell’umanita. The objects list of the collection can be viewed online at www.municipio.re.it/catalogomuseo/musei.nsf/Etno?OpenForm.

39 A link to the Progetto Mothers videos can be found on the Chierici Museum website, www.musei.re.it/multimedia/video/.

40 Goethe, Viaggio in Italia, 1816–1817, 1829, vol.II, p. 1. London, Folio Society, 2010.

41 John Glassie, A Man of Misconceptions: The Life of an Eccentric in an Age of Change, Riverhead, New York, 2012, p. xv.

42 See Cooper, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections, for object lists.

43 At the time of writing, Philip Jones from the South Australian Museum was studying this collection.

44 C Rocchi, ‘Australia’, in Il Museo Pigorini, Edizioni Quasar, Roma, 1976, p. 49.

45 ibid.

46 ibid., fig. cat. 6697.

47 ibid., fig. cat. 6692.

48 ibid., inv. 9488; inv. 75 and 9486; cat. 98448; cat. 59256.

49 ibid., inv. 9486.

50 Schmidt founded Anthropos in 1906, which became an internationally famous journal of ethnography and languages, and the Anthropos Institute, which he directed from 1932 to 1950. He escaped the Nazis and fled to Switzerland in 1938.

51 W Schmidt, Die Gliederung der Australischen Sprachen : Geographische, bibliographische, linguistische Grundzüge der Erforschung der Australischen Sprachen,Mechitharisten-Buchdrückerei, Wien, 1919.

52 ‘Address of John Paul II to the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in “Blatherskite Park”’, 29 November 1986, http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/speeches/1986/november/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19861129_aborigeni-alice-springs-australia.html.

53 Fr Eugene Perez, Kalumburu. The Benedictine Mission and the Aborigines 1908–1975, Kalumburu Benedictine Mission, Western Australia, 1977, p. 32. For more detailed information on the Australian collection, see the forthcoming Australian catalogue of the Vatican Ethnological Museum.

54 Known for his work on languages, Worms demonstrated a comprehensive knowledge of at least 26 Aboriginal languages. In 1961 he became a member of the Institute of Aboriginal Studies in Canberra. His book Australian Aboriginal Religions was published posthumously in 1986.

55 Personal communication with author in Melbourne, 2013

56 On this occasion, a Canadian First Nation elder visited the museum and saw a peace pipe on display which had been given to Pope John Paul II at the World Day of Pray for Peace at Assisi in 1986, which initiated a discussion for a ‘smoking ceremony’ of the Canadian objects which, it was believed, would draw a link between the objects and the living cultures today.

57 For other histories of collecting see, for example, N Peterson, L Allen & L Hamby (eds), The Makers and Making of Australian Indigenous Collections, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2008;T Griffith, Hunters and Collectors: The Antiquarian Imagination in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996.

58 For example, see the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa website: www.tepapa.govt.nz/collectionsandresearch/taongamaori/Pages/default.aspx.

59 See Leonn Satterthwait, Collections as Artefacts, in Peterson, Allen & Hamby (eds), The Makers and Making of Australian Indigenous Collections, p. 70.