Objectives

Launched on 29 August 2014, the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History project centres on the proposition that ‘the Australian story’ is punctuated by specific points – moments – at which ‘something happens’ that serves to ‘move us in a different direction, or to transform the way we think about ourselves’. The project uses a mix of elements to capture this synthesis between a continuing, collective record – ‘the Australian story’ – and a broad invitation to consider and contribute to a listing of such particular, decisive moments of national reorientation, rupture or reappraisal.

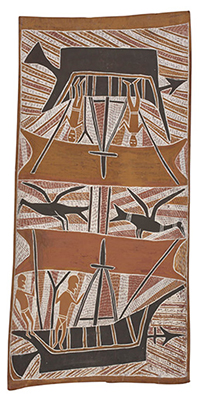

photograph by Jason McCarthy

These objectives are laudable, and increasingly familiar. They reflect the ‘crossroads’ in Australian history that Paula Hamilton and Paul Ashton discussed in 2007: the uneasy intersection of politicised concerns to get national history right and a popular enthusiasm for a ‘pastmindedness’ at which multiple versions of, and identifications with, history seem in play.[1] Relevant also is the 2008 invitation from Martin Crotty and David Roberts to consider those ‘turning points’ that either reflected decisive moments of change in the national story, or prompted reflection on hypothetical alternative paths.[2] That such perspectives are so much of our own ‘moment’ underscores the need to reflect as much on their context as on the achievement of that elusive goal: a more inclusive, reflective national story. The Defining Moments project serves to refocus our attention on both questions.

Join the conversation

At the project’s core is a website and social media address inviting comments on, debate over, and contributions to an initial list of 100 such ‘moments’ that were identified by a panel of leading Australian historians. Here the National Museum of Australia embraces the ‘interactivity’ its current director, Mathew Trinca, has urged museum practice to adopt, recasting its audience as active participants ‘who act upon and inform the museum’ rather than as subjects of its ‘educative will’.[3] In the Museum itself Defining Moments is represented in the display of a small number of objects (five initially, currently three) in the Main Hall. While the project website continues to use items from the Museum’s collection (or elsewhere) when appropriate, the virtual and event focus of the project signals a departure from the rather strict tests of object-centredness that the Museum has observed in the past.

The National Museum of Australia’s Main Hall also contains a digital display outlining the project, with cards inviting written responses to the list compiled by the experts. Modest at the moment, this resource is envisaged as becoming a more central element in visitors’ experience of the Museum, finding a prominent place among the large objects that began to greet arrivals in the Main Hall a few years ago. The cards invite contributors to nominate ‘Australia’s most significant defining moment’. The singular of this option, and the tension at present between the small screen and the landau and traction engine that loom nearby, in themselves suggest some still evolving edges to this ‘hard’ version of Defining Moments, in contrast to the inevitably more open experience of an interactive web page.

The Main Hall also features a plaque commemorating Captain Arthur Phillip’s establishment of the convict settlement at Sydney Cove in 1788, which was unveiled at the launch of Defining Moments in August 2014. On 20 March this year another plaque was unveiled, this time commemorating Pemulwuy, the Bidjigal man who led Aboriginal resistance to colonists until he was killed in 1802. A series of such events are proposed over time, each envisaged as a stimulus to the conversation that is central to the project. The final placement of the plaques is still under consideration – and will test the capacity of the building itself to focus on more traditional modes of commemoration. Phillip’s is set in the floor at present, and easily missed in the scattered contrast of tiles that reflect the ‘tangled vision’ of the building’s fundamental conception.

photograph by Jason McCarthy

Across these dimensions, Defining Moments reflects an aspiration to embrace the virtual and promote the plural, if with the kick-starter and sanction of authority provided by the experts who assisted in compiling the initial list, and a certain tension with this lingering, older style of memorialisation. The website gives those experts as Professor Judith Brett, Professor Rae Frances, Professor Bill Gammage, Dr John Hirst, Dr Jackie Huggins, Professor Marilyn Lake and Professor John Maynard – an impressive team of specialists in political, cultural, social, environmental, gender and indigenous history. A sense of balance is perhaps self-consciously sought in this mix – all bases are covered – but so is a commitment to inclusiveness and the vision of a dynamic outcome, as the contest of contending ‘moments’ unfolds over time. The term ‘project’ itself reflects the commitment to a more unfolding, directed kind of outcome than is usually associated with elements of display or other set events in museum programs. And it underscores that this is a ‘work in progress’. Just over six months into its development, how is this initiative faring?

The original goals are commendable. ‘We hope to take the discussion into classrooms and universities’, the Defining Moments website states: ‘into local historical societies and even the local pub’. That is an ambitious reach. It travels one of those highways identified by Hamilton and Ashton: the traffic in histories that people are creating to reflect their own memory, identity and affiliation. Embracing it, the National Museum of Australia appears to be breaking with reservations regarding the ‘amateur’ that have characterised recent demarcations between the role of the ‘museum’ proper and the ‘cabinet of curiosities’ emerging from local, untutored practice.[4] Equally ambitious is the Museum’s pledge that ‘the success of the program will be gauged by the level of public involvement’, and by its capacity to promote a ‘national debate about our nation’s past’.

But some shadows are lurking within these objectives – especially that drumming emphasis on ‘nation’. In 2009 Kevin Rudd called a ‘truce’ in the ‘history wars’ that had exerted both a polarising and enervating influence over Australian history from the 1990s onwards, with its bitter exchanges over what should constitute the national narrative.[5] But embers still flicker in the fires of opposing camps. Prime Minister Tony Abbott, launching Defining Moments and unveiling Arthur Phillip’s plaque, provoked a flurry of controversy with his remark that the arrival of the First Fleet was the (he repeated the) ‘defining moment in Australian history’.[6] Whether balance, diversity, interactivity and debate will be enough to move beyond this unsteady truce is one of the questions that the project must address.

photograph by Jason McCarthy

Origins of the project

The origins of Defining Moments underscore this tension. At its launch, Michael Ball, an early advocate and one of the official patrons of the project, reflected that a personal prompt for the venture had been a concern that the National Museum of Australia’s exhibitions had ‘no flow, no logic’. It was not always clear, Ball argued, what criteria had determined which objects should be displayed in the Museum, or the relative importance of the areas of national history that they were intended to illuminate. Such criticism of the Museum is far from new. As former Museum curator Ian McShane noted in this journal in 2007, the Museum was an early target for the concern – supported if not orchestrated by the then Commonwealth Government – that Australians deserved a more coherent view of their past, illustrated by ‘numinous objects’ that would draw visitors to a shared and unifying history.[7] The triad of themes that had shaped the Museum’s genesis – a questioning reflection on the meanings of ‘land, nation and people’ – seemed to many early commentators potentially disorienting, and to a powerful few the approach was judged openly antagonistic to the idea that a shared culture defined the nation. An earlier iteration of a chronological strand to help visitors navigate larger themes, called simply ‘moments’, was developed within the ‘nation’ module to allay such concerns, but clearly they endured. Ball’s criticism of 2014 was offered in more constructive tones than many in the past, but carried its own distinct authority.

Described in 2010 by the Sydney Morning Herald as a ‘mercurial septuagenarian’, Michael Ball was a pioneering Australian advertising executive who has more recently served on the boards of a range of organisations, including as chairman of the National Trust’s National Living Treasures committee.[8] As early as 2002, Ball had developed the concept of ‘defining moments’ as a corrective to a perceived drift in popular awareness of Australian history. He was soon joined in his campaign by Michael Kirby, until 2009 a Justice of the High Court of Australia. They engaged Geoffrey Blainey – an eminent historian, but also a prominent protagonist in the history wars – as a consultant in developing the concept to a sufficient level of detail that it could be presented for support to the government under John Howard.

A document on Kirby’s personal website indicates that a separate museum in Canberra’s Commonwealth Place was the preferred location for the venture, ideally to be supported by private funding, although the National Museum of Australia – in association with the National Capital Authority – was eventually conceded to be ‘the most likely and logical’ partner.[9] Ultimately, it seems, the Museum shouldered the full responsibility for realising the idea. By 2006, Kirby – as recorded in another document on his website – had decided to withdraw from further association with the project on the basis that decisions made by a, at that stage, small joint committee were being overridden in largely unaccountable ways on the basis of presumed political and community acceptability.[10] The Defining Moments website now refers to Ball and Kirby as ‘patrons’, although their support is presumably moral rather than financial. At the August launch the chairman of the Museum’s council, Daniel Gilbert – the founder of a leading national law firm who assisted in gaining a trademark for Ball and Kirby’s project and protecting its intellectual property – confided that he had been forcefully reminded of their enthusiasm for the venture on his appointment to that position in 2012.

This frank account of origins is disconcerting: Defining Moments could seem to be another therapy to be applied to the National Museum of Australia, rather than an initiative generated by it. The project would appear to be one the Museum was tasked to undertake, rather than one it developed from its own priorities and expertise. A draft charter on Kirby’s website declares the core intention of Defining Moments to be the ‘celebration of Australia’s history’, and while the open forum of an ‘electronic outreach’ facility, seeking especially to engage school children in discussion, was seen as central to the concept from its first formulations, so was the desire to promote ‘pride’ in Australian history.[11]

From conception, then, the project had a mission that might sit uneasily with the more ‘objective’ remit of a national cultural institution, and jar at least a little with the ‘instrumentalism’ that Mathew Trinca has questioned in museum practices. It can also, however, be seen to have a place in the gradual process of repositioning that the National Museum of Australia has undergone over the past decade – a process in which the challenge of ‘land, nation, people’ has been rebranded as ‘where our stories live’, offering a more inclusive, affirming fusion of individual and collective experience. This is not to suggest that Defining Moments has not been made the Museum’s own, but the evolution of the project at least underscores the kind of ‘crossroads’ at which it – the project, and perhaps the institution – now sits.

Obstacles and pitfalls

‘Pride’ was not one of the emotions that the National Museum of Australia sought to evoke, in one of its many early innovations in exhibition design, as part of the Australian experience.[12] Pride is not emphasised in setting the terms for the debate Defining Moments now seeks to foster (although it is the first theme the visitor encounters on entering the Museum’s current exhibition, The Home Front: Australian during the First World War).[13] Even so, within Defining Moments there remains a tension between a list of moments that are presented as reflecting a coherent ‘national story’, and the invitation to contest them in terms that still, presumably, fall within a sense of that shared path. At the August launch, Daniel Gilbert reflected that ‘all of our histories are important to all of us – as variable as they might be’. But what are the limits to those variations within a project premised on a national ‘flow’ and ‘logic’?

National Museum of Australia

The National Museum of Australia is not alone in having to deal with these questions. They are a part of the wider positioning of historical knowledge within concerns at wavering social cohesion and capacity. Since the 1990s, Australia’s national curriculum debate has been spurred by alarm at the ‘civic deficit’ evident among students who don’t know, or misunderstand, core aspects of their heritage.[14] Educators have protested at the extent to which Australian content has become a kind of commodity ‘to be desired, worked for and consumed’ in these processes, with a ‘use’ value much narrower than evaluation and judgement.[15] That everybody should have a voice now has also been seen as undermining the capacity to reflect on the factors that might account for why they did not have one then. A contemporary political culture that is framed by a sense of connection and empathy, as Bain Attwood worries in relation to Aboriginal history, might have the effect of minimising the ‘distancing’ of students from their subject that is central to exploring and understanding the differences between the present and the past.[16] Equally, it is clear that defining what that core knowledge should be, and how much of it can effectively be fitted into a meaningful, comprehensible and assessable package, is a daunting task. As the serial attempts to frame a national curriculum in history suggest, the more content that is added, the less effective its teaching can be, and the more disenchantment is generated among all interested parties.

In museums, too, as Stephen Lubar shows, there has been an increasing awareness that the ‘natural’ model of chronological progression in presenting exhibitions has an in-built determinism that can fail to generate visitor engagement, discourages independent critical reflection, compounds the marginalisation of some groups, and – in any case – is likely to be overridden by the personal interests that visitors act on in navigating their way through galleries.[17] History educators in the United States are fond of quoting the limp remark made by cartoon character Marge Simpson to her son as indicative of the heavy hand a fact-driven pedagogy has laid on their discipline: ‘Come on, Bart: History can be fun. It’s like an amusement park except instead of rides you get to memorize dates!’[18]

It is not that timelines – the steady sequence of significant dates – have been fundamentally discredited: Lubar, for example, argues they retain a kind of inevitability. But their purpose and presentation now require closer and more creative thought. Some commentators argue that the capacity of current students to comprehend multiple, concurrent timelines has been greatly enhanced by digital culture, which has probably generated expectations among those students that such experiences and competencies will be acknowledged elsewhere in their lives.[19] Those competencies might be up for scrutiny, but the expectations can hardly be disregarded. The most effective use of timelines, some teachers have found, arises when the focus is not simply on one event, but on ways of using a sequence or contrast of events to encourage students to explain ‘how and why things changed’. The goal is to encourage a way of imagining or experiencing that changes not in terms of direct identification with a particular period, but through a deliberate attempt to disrupt such a connection by asking students to experiment with different roles and values.[20] Reflection on processes or trajectories of change, rather than on specific moments of transformation, seems most likely to promote learning. The challenge of ‘defamiliarising’ the past is, after all, widely regarded as central to historical learning.[21]

The project underway

Turning to Defining Moments itself, to what extent does its gestation (however surrogate) and these wider reflections help us make sense of the project underway?

The 100 moments emerging from the advice of the National Museum of Australia’s expert panel are a thorough and, largely, balanced sample. They range from archaeological evidence of human occupation of the Australian continent, at least 52,000 years ago, to the 2009 ‘Black Saturday’ bushfires in Victoria. In between, exploration, innovation, adaptation and recreation are central themes. Dingos arrive, as do convicts, sheep, immigrants and rabbits. Protestant and Catholic churches are funded, railways opened, mines dug, franchises extended, unions formed, irrigation introduced, and legislation passed on things ranging from wages to welfare. Australian Rules is played, the first Melbourne Cup is run, the Heidelberg painters exhibit, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is founded (and later the Special Broadcasting Corporation), the ‘Bodyline’ scandal erupts, and the Sydney Opera House is opened. Protest features prominently – from Eureka to the Franklin River. Rights are asserted, from women’s suffrage to the first Gay Mardi Gras march. The world impinges: from the bombing of Darwin to the bombs in Bali; it is embraced in war, in Australia’s prominent role in founding the United Nations, or in floating the dollar; or it is kept distant – with White Australia, immigration detention centres and the Tampa. The coverage is detailed, diverse, and invites a broad sense of a nation to be shared.

Arching over all these moments, however, politics is the core motif, in parties and policies, in leaders and leadership. Perhaps ‘the nation’, and particularly the challenges of a federation, inevitably privileges the coherence that is sought in government. Underneath that span, science has a brief flourish in the development of penicillin. Aboriginal Australians are a more constant refrain, from trade with the Makasar to Myall Creek, land rights, Mabo and a national apology. But even here the narrative largely marches to a tune of civic awareness: the moments that define recognition of Aboriginal people within the nation. Overall, there are no surprises, but several thoughtful inclusions – oral contraceptives, for example (again, access being negotiated through government). The experts’ list, perhaps of necessity, was inclined to the iconic. And gradually their selected ‘featured moments’ are being expanded by curators and museum researchers with succinct, informative online essays of around 750 words exploring their significance. The essay on ‘the pill’, for example, explains its importance in giving ‘women the freedom to avoid unwanted pregnancies and plan parenthood’. The essay on the passing of the 1966 Migration Act ends by noting its significance in confirming a process of reform which led, through the multiculturalism of the 1970s, to Australia becoming ‘home to migrants from about 200 different countries’. Destinies, rights, identity markers are steadily affirmed.

National Museum of Australia

Still, this brief survey might suggest that while ‘celebration’ is far from overt, the diet is earnest and improving. This fare is likely to fare better in the senior classroom than the pub – but it is too early to tell much about use patterns of the site. Still, one of the project’s real contributions will be the perspective it offers on what captures the attention of those who come to the site.

Progress so far

From the data so far available, some trends are evident. The ‘evidence of first peoples’ moment has – as of 18 February 2015 – one of the highest rates of visitation (508 page views), but so does the launch of the first Holden (361). Cyclone Tracy, Bodyline, the pill, women’s suffrage and the national apology have held their visitors for comparatively longer than most other moments (above three minutes), but it is hard to see any pattern in such traffic.[22] Those registering support for the initial 100 moments have by far favoured those dealing with recent Aboriginal issues, especially Mabo and Kevin Rudd’s Apology to the Stolen Generations. Beyond these raw numbers (which are not in themselves large), those posting on the ‘join the conversation’ page of the website offer another reflection of views of the project – the ‘conversation’ that is at the heart of the venture. These responses can’t be said to be representative, but some common themes emerge.

photograph by Dragi Markovic

These contributions are, for the most part, considered and constructive. They convey strong views and, often, considerable knowledge on the part of many of those adding a comment or suggestion. To that extent, an exchange is clearly underway: people care about what is included, and more about what is not. One feature of that conversation, not surprisingly, is that the moments often suggested for addition reflect a regionalised perspective – some even protesting that the nation defined by most of the initial 100 moments was essentially a rather insular south-eastern enclave, and reflected ‘trumpeted southern developments’. The local association is imperative in these posts. ‘The first mosque built in 1861 at Marree, South Australia’ and the 2011 Queensland floods are among suggested additions. Others protest that the Myall Creek massacre, for example, was not so much a ‘defining’ moment as a ‘moment of shame’ – an interpretation of the list that suggests it is implicitly read in terms of a theme of progress. A few are trenchant, one judging the first list as ‘an ideologically correct selection of white moments and English triumphalism’. Special interests are frequently evident – ‘I can’t believe you haven’t included Australia II win of the America’s Cup in 1983’; ‘Moon landing and Australia’s involvement’. Some posts are sufficiently well informed in pointing out mistakes or questioning interpretations to lead to a grateful acknowledgement on site from National Museum of Australia staff. The ‘DM team’ responds enthusiastically to several suggestions. But there seems so far to have been no exchange among those who post: the conversation is largely one-sided.

The main impression gained from the ‘moments’ being suggested by the public, either on the web or on cards completed in the Museum, is that the political focus of the ‘experts’ list is not matched by the popular view of what matters. Environmental and Aboriginal perspectives are prominent in these ‘alternative moments’ – and presumably in the ‘different directions’ those contributing them see as defining Australia. A grateful teacher writes to note that he is using the Pemulwuy and Vinegar Hill rebellion moments – the latter not a part of the initial 100, but developed by Museum staff in response to an early recommendation that it be included. ‘This list seems very biased towards politics and economic moments’, observed another post in February: ‘what about Patrick White’s 1973 Nobel prize for literature – for an epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature?’.

It would be fair to say that the total number of visits (a total of 22,500 page views to 18 February) and comments so far recorded fall short of the ‘national debate’ the National Museum of Australia is seeking. True, the project is continuing, but the peak of the site’s usage came within weeks of its launch and has largely flatlined since then. What is emerging is not so much a discussion about the ‘national story’, but more a series of voices that are cutting in at levels below the nation, seeking recognition of more localised ideas of place and identity. In itself, this is indicative of a conversation waiting to be had, of the ‘crossroads’ where the traffic reflects journeys that are underway in the minds and experience of Australians. The question remains, however: how effectively can those journeys be garnered into a project built on the particular premises of Defining Moments. An older Museum might say: here is proof of our foundational premise – land, nation, people. A newer Museum has to wrestle with the task of finding a frame in which all such stories can live, and of resourcing the capacity to respond to them.

Still, and in ways that will prove helpful in these large and continuing debates, the National Museum of Australia aspires ‘to develop a language for frank discussions about our past, from moments of success and celebration to those that are much more challenging’. That ‘language’ is still to take shape, and to settle on a field of reference that makes sense to people. Historian Richard Evans observed of Crotty and Roberts’ concept of ‘turning points’ that, innovative as it was in supplanting the wisdom of hindsight, it could never quite avoid the sense that the purpose of the road was to get to where we are now.[23] The radical challenges of historical change and contingency were somehow defused at the crossroads, the paths taken and not taken. But is it that simple?

To some extent, it might be in the more orthodox, even ‘old-fashioned’ dimensions of Defining Moments that the project will find its purchase – and in ways that bring the role of the Museum to the centre, rather than leaving it as a service provider. When Christopher Pyne, Commonwealth Minister for Education, unveiled the Pemulwuy plaque in March he vowed that he would continue in his personal quest to ensure that, if at all possible, the warrior’s skull would be returned to his people from whatever vault it disappeared to after being sent to England. In reply, Vic Simms, a Bidjigal elder representing the La Perouse Aboriginal Community in Sydney, welcomed that commitment, and the National Museum of Australia’s selection of Pemulwuy as a focus for a public occasion that could make a contribution to assisting ‘the people prepared to take on the learning’. The hard fact of a plaque to be unveiled (actually, it unveiled itself) mattered: it offered recognition, and carried the authority of the Museum as an agent in public education. These are specific priorities that might be built into the project, not so much as moments but as campaigns and capacities: the issue of the return of human remains to appropriate communities, the provision of knowledge to specific communities. The evolution of these elements within the project might not sit easily with the collective narrative of ‘ourselves’, but would seem to remain integral to the conversations it seeks to generate. Ultimately, some form of curatorial intervention or framing still matters.

A possible future

Some guidance for that evolution might be taken from a comparable initiative across the Tasman. Nation Dates is a pocket-sized book produced by the McGuinness Institute in New Zealand. Supported by a charitable trust, the institute is a non-partisan think tank which offers ‘strategic foresight through evidence-based research and policy analysis’. It is, plainly, not a ‘national cultural institution’, with the baggage that term has come to carry. The institute places a priority on ethical outcomes: on securing a ‘long-term sustainable future of New Zealand and the wellbeing of its people’. Nation Dates – subtitled ‘Significant dates that have shaped the nation of New Zealand’ – might seem an odd product from such an agency. But the institute’s argument is that the past is vital to envisaging the future, not as series of defining events, but as patterns of change and adaptation. Now in its second edition, it is 250 pages long and offers a timeline of some 525 events ‘in the evolution of our nation’.[24]

That scale and intent might suggest it is a perfect candidate for Marge Simpson’s amusement park. But what distinguishes the McGuinness Institute’s approach is that its timeline is also rendered as a series of patterns and connections, enabling readers to trace through it as a series of ‘historical threads’ – ranging from constitutional through economic, social, environmental and international connections – and under major headings and cross-references. The focus of the book is precisely on assisting readers to chart processes of change that can be seen over time, and potentially projected into the future. The timeline can be ‘read’ as a series of connections and transformations according to areas of interest. Like Defining Moments, the institute hosts a website that invites suggestions for new dates, and for the next edition a further 85 dates will be added and woven into these ‘threads’.

Clearly, the McGuinness Institute does not have the broad public remit of the National Museum of Australia, nor the public accountability. But its approach builds into its timeline an active role for readers in assembling a series of links, contrasts and uses. Defining Moments might benefit from reflection on ways to generate an equivalent exchange, so that its ‘moments’ not only reflect the volunteering of ‘all of our histories’ within the catch-all of ‘the nation’, but also begin to work with the issues, patterns of experience and layering of identities and affiliations that are emerging from engagement with the project. To make the meanings of the ‘nation’ itself a point of exploration – and to embrace the extent to which they are not self-sufficient or self-evident – would free the project further from the ‘instrumentalism’ that has shadowed its origins.

Endnotes

1 Paula Hamilton & Paul Ashton, History at the Crossroads, Halstead Press, 2007.

2 Martin Crotty & David Roberts (eds), Turning Points in Australian History, UNSW Press, 2008.

3 Mathew Trinca, ‘History in museums’, in Anna Clark & Paul Ashton (eds), Australian History Now, NewSouth Books, 2013, pp. 145–6.

4 See Chris Healy, From the Ruins of Colonialism: History as Social Memory, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 78; for discussion of these concerns, see Takao Fujikawa, ‘House of history: Academic history and history in society’, Journal of History for the Public, no. 11, 2014, pp. 113–16.

5 See Phillip Coorey, ‘Rudd squirmishes with Howard over the history wars’, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 August 2009; Alison Clark, History’s Children: History Wars in the Classroom, NewSouth Books, 2008.

6 See Benjamin Jones, ‘Modern Australia’s defining moment came long after the First Fleet’, The Conversation, 4 September 2014.

7 Ian McShane, ‘Museology and public policy: Rereading the development of the National Museum of Australia’s collection’, reCollections, vol. 2. no. 2, 2007, p. 202.

8 Harold Mitchell, ‘Ogilvy and Mather decides it’s time to throw a party’, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 June 2010.

9 See Michael Kirby, ‘Defining Moments in Australian History Project’, http://www.michaelkirby.com.au/images/stories/speeches/2000s/vol57/2005/2055-DEFINING_MOMENTS_OCTOBER_2005.DOC (accessed 2 April 2015).

10 Kirby gives the membership of that first ‘joint committee’ as Michael Ball, Annabelle Pegrum (then chief of the National Capital Authority), Craddock Morton (then director, National Museum of Australia), the historian Dr John Hirst, and Tony Staley, who had served as the federal president of the Liberal Party of Australia. Of particular concern to Kirby was the proposal to delete from the first list of ‘moments’ the first Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras (which is on the current list of 100) and Bringing Them Home, the Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families (which is not on the list). These were to be replaced by the Howard government’s gun buyback scheme and the free trade agreement with the United States, both of which are among the current 100. See Michael Kirby, Defining Moments Handover Report, http://www.michaelkirby.com.au/images/stories/speeches/2000s/vol60/2006/2139-Defining_Moments_-_Hand-Over_Report.pdf (accessed 2 April 2015).

11 See ‘Defining Moments in Australian History’ at http://www.michaelkirby.com.au/images/stories/speeches/2000s/vol59/2006/2101-Defining_Moments_of_Australian_History_-_Charter.pdf (accessed 2 April 2015).

12 The Museum’s Eternity gallery explores the emotional registers of home, chance, devotion, fear, hope, joy, loneliness, mystery, passion, separation and thrill.

13 The other emotions in this exhibition are sorrow, joy, wonder and passion.

14 Civics Experts Group, Whereas the People: Civics and Citizenship Education, AGPS, 1994, pp. 13–14.

15 Terri Seddon, ‘National curriculum in Australia: A matter of politics, powerful knowledge and the regulation of learning’, Pedagogy, Culture and Society, vol. 9, no. 3, 2001, pp. 319–20.

16 Bain Attwood, ‘In the age of testimony: The Stolen Generations narrative, “distance” and public history’, Public Culture, vol. 20, no. 1, 2008, pp. 92–4.

17 Steven Lubar, ‘Timelines in exhibitions’, Curator, vol. 56, no. 2, 2013, pp. 169–88: my thanks to Stephen Foster for this reference.

18 Simpsons episode ‘Magical History Tour’, first screened 22 December 2004, quoted in Michael Edmonds et al., History and Critical Thinking: A Handbook, Wisconsin Historical Society, 2005, p. 4.

19 See Gary R Edgerton & Peter C Rollins, Television Histories: Shaping Collective Memory in the Media Age, University Press of Kentucky, 2001.

20 Janet Alleman & Jere Brophy, ‘History is alive: Teaching young children about changes over time’, The Social Studies, vol. 93, no.3, p. 108.

21 See Sam Wineberg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2001, pp. 3–24.

22 Thanks to staff of the National Museum of Australia for supplying the ‘analytics’ of use of the Defining Moments site.

23 Richard Evans, ‘Review of Martin Crotty and David Roberts’s Turning Points in Australian History’, History Australia, vol. 6, no.3, 2009, p. 86.

24 Wendy McGuinness & Miriam White, Nation Dates: Significant Events that Have Shaped the Nation of New Zealand, Creative Commons, 2012.