by Valda Rigg

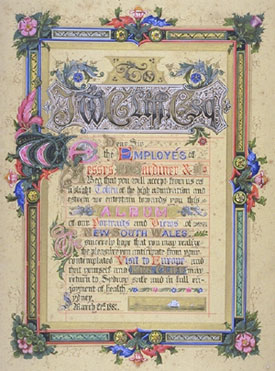

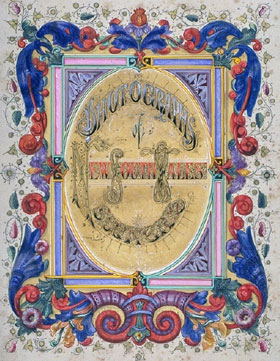

In March 1882 as Mr JW Cliff, a partner of WG Gardiner and Company, Importers and Warehousemen, prepared for his departure to England, the employees presented to him an illuminated album containing professional photographic portraits, and rural and urban views of New South Wales. Each of the album's 50 pages was decorated with exquisite medieval-style illuminations.[1] The album was produced to commemorate Cliff's departure for Europe with his family and was offered, the 'grateful employés' stated on the title page, as 'a slight token' of the 'high admiration and esteem' in which they held Cliff. With dimensions of 480 x 410 x 5 centimetres and weighing 8 kilograms, their token of admiration and esteem seems anything but slight.

It has been shown how close study of an Australian illuminated address can 'reflect the social, historical and artistic' themes of its time, making these artefacts valuable historical tools.[2] There are many extant nineteenth-century illuminated addresses and presentation albums that can demonstrate this but the Cliff album is a rare artefact of its time. This is due not only to its size but also because it provides an exceptional visual record of colonial life and commerce in late nineteenth-century New South Wales. The album's inherent artistic value is obvious, as is its documentary evidence of the economic importance of nineteenth-century warehousing. But placed in a wider context it reveals cultural, economic and imperial issues that range through the romantic nostalgia of the nineteenth-century revival of medievalism in Britain and Australia, mercantilism, and the exhibition movement in colonial New South Wales. The Cliff album brings together in one resource the nineteenth-century medieval aesthetic and the colonial imperative, elements which stimulated, nourished and drove the capital economy and culture of the British Empire as it promoted an orthodoxy of imperialism in the 1880s.[3]

Medievalism was not as vigorously adopted in Australia as it was in Britain but it was a useful ideological tool for colonial ambition and endeavour.[4] Stephanie Trigg and others have analysed the impact of medievalism on Australian culture and literature,[5] and Sarah Randles, writing on neo-medieval architecture, argues that 'the medieval idiom often becomes symbolic of such conservative qualities as continuity, stability, wealth ... and tradition'.[6] Another less conspicuous but significant visual manifestation was the revival of medieval illumination found in manuscripts, addresses, books and presentation albums. The Cliff album demonstrates this, and conveys the aforementioned symbolic qualities. The artefact also demonstrates facets of metropolitan and rural development and signals links to mercantilism and economic conditions in colonial New South Wales. This paper will consider these links and discuss the ways in which the artefact also illuminates the artistic revival of medievalism.

Colonial use of illumination was a symptom of the medieval revival movement in England, expressed in neo-Gothic architecture, art and a renewed notion of chivalry. In his comprehensive account of the revival of chivalry in the nineteenth century Mark Girouard reveals the significance of its social and cultural impact.[7] He writes that nostalgia for chivalry had simmered in English society since the end of the eighteenth century. In 1787 George III bestowed his royal imprimatur on chivalry by commissioning Benjamin West's Garter series of paintings.[8] He also advocated British craftsmanship,[9] which would have given impetus to the revival of medieval illumination. Although the practice of knightly chivalry had little relevance at the turn of the century, an antiquarian cultural interest began to ferment, inspired by writers, most notably Walter Scott. The aftermath of the French Revolution abroad and the suggestion of social change at home, fanned by the utilitarians who were questioning the social order, prompted a cultural response by some scholars and artists to create works that referred to chivalry. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the idea of a pure and specifically Christian chivalry was being visually expressed in many forms, such as the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites and in book illustration. SC Hall's The Book of British Ballads[10] featured elaborate black monochrome medieval decoration and chivalric illustrations, and more appeared in translations from the German of Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's Sintram and Undine.[11] The young Oxford scholar, William Morris, was one of many people influenced by these neo-medieval books.[12] Morris later became a highly successful and acclaimed decorator, and the driving force behind the Arts and Crafts movement. At the London International Exhibition of 1862 his firm presented neo-medieval design to a wide audience and a favourable reception.[13] Morris's 1870 graphics for Ode to Horace is typical of his famous medievalist style.[14]

In 1839, when a young Lord Eglington and his aristocratic coterie recreated a medieval tournament at Eglington Castle, medievalism was used as a public spectacle and, to some extent, as a symbolic statement of conservatism.[15] Staged over several days, the event included all the panoply and pageantry of those of the Middle Ages. Despite some inclement weather the Eglington Tournament attracted a large cross-section of the public and much attention beyond the United Kingdom.[16] Three years later, inspired by the visual aesthetic of the Eglington Tournament, Queen Victoria staged a royal bal costumé where she and Prince Albert dressed as the fourteenth-century Queen Philippa and Edward III to welcome their 2000 guests, many of whom attended in medieval costume.[17] Medievalism came to a mass domestic and international audience with the staging of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of 1851 (hereafter the Great Exhibition), which was driven by Prince Albert, who, like Victoria, was intrigued by medievalism. Exhibition historian Peter Proudfoot notes that the semiotics of the Great Exhibition, staged in the 'Crystal Palace', included 'flags, banners, bazaars, tents and exotic paraphernalia — the legacy of medieval games and rural fairs'.[18] This benign and romantic version of chivalry offered the disadvantaged underclass an ideological escape from their increasing social distress in the industrial age. Public articulation of an idealised medieval past in spectacular events such as the Great Exhibition could provide the masses with an alternative vision to their harsh surroundings, while the brutalities of the medieval era could be submerged in the artistic and comforting distraction that its cultural revival offered.

The institution of knighthood, although largely ceremonial by the nineteenth century, was given new cachet under Queen Victoria, who increased its orders from a few hundred to almost 2000.[19] In 1869, when the Order of St Michael and St George was granted to the colonies, it became a much desired honour for those who craved the aura of vice-regal association.[20] Even if some thought its knightly physical practices to be anachronistic, nineteenth-century chivalry's material culture of costume, heraldry and regalia transmitted a conspicuous message of gallantry and provided an aura of nobility and heritage. Neo-Gothic architecture, literature and art created a visual culture that presented to a wide audience the ethos of chivalry and a credo of imperialism. The work of Owen Jones, William Morris and John Ruskin encouraged manifestations of medievalism and advanced the artistic revival of medieval illumination and illustration in written and artistic works.

These works began to flourish from the middle of the nineteenth century, and were usually based on the richly illuminated Books of Hours that proliferated amongst the literate of the middle ages, before the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century. These books were small bound manuscripts containing the Hours of the Virgin, which were prayers and psalms venerating the Virgin Mary for each of the eight canonical hours.[21] In his 1858 painting Queen Guinevere, William Morris shows Guinevere looking downwards towards a book of hours on her dresser. These missals, and larger works, often featured 'miniatures': small pictures that provided decorative appeal as well as a visual aid to the narrative.[22] While illuminated manuscripts proliferated within European and Islamic cultures, the most famous British examples are the seventh-century Lindisfarne Gospels and the ninth-century Book of Kells. These larger volumes were created for use on the altar and each retold the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Visual allusions to these works, as well as many others, appeared frequently in the nineteenth century. In their 1860 instruction manual on illuminating, art scholar and architect MD Wyatt and calligrapher/illustrator WR Tymms provide copious examples and patterns for emulation. However, Wyatt, in his extensive and comprehensive essay on manuscript history, style and technique, warns against anachronism:

If you adopt any historical style or particular period as a basis on which your text, miniatures, and ornamentation are to be constructed, maintain its leading features consistently, so as to avoid letting your work appear as though it had been begun in the 10th century, and only completed in the 16th; or, as I have once or twice seen, vice versâ.[23]Perhaps the most influential advocate of medievalism and the neo-Gothic was John Ruskin. His appointment in 1869 as University of Oxford's first Slade Professor of Fine Art gave him huge artistic authority at home and throughout the Empire. Through his Guild of St George he expressed his vision for an ideal society, albeit a quasi-feudal one.[24] Although this quest was ultimately a failure, it demonstrated his ardent belief in chivalric ideals. His conviction that art could convey moral and transcendental elements permeated his teaching and he believed an appreciation of art's beauty would enlighten the working man.[25] His 'visions of guilds and gothic workmanship'[26] must have nourished many an artisan's fondness for medieval illumination. His disciples heeded his admonition that 'every good piece of art, to whichever of these ends it may be directed, involves first essentially the evidence of human skill, and the formation of an actually beautiful thing by it'.[27] Thus, those involved in the colonial process of commission, execution, presentation and receipt acquired a chivalrous semblance that offered a historical continuity with the mother land.

Ruskin's teachings had some impact on colonial Australia during the later decades of the nineteenth century,[28] if not quite to the extent that they had done in Britain. In 1870, in an acclaimed lecture replete with the language of chivalry and imperialism, Ruskin challenged aspiring young colonists to go forth and remind other 'colonists that their chief virtue is to be fidelity to their country, and that their first aim is to be to advance the power of England by land and sea'.[29] The Australian visual response to Britain's Gothic revival was most obvious in architecture, but the skills and artistry of medieval illumination offered further assurance that continuity with the British past had not been fractured in the colonies. An array of illuminated addresses and documents testifies to this and shows that colonial society understood how the ruthless efficiency of the machine was undermining traditional skills.

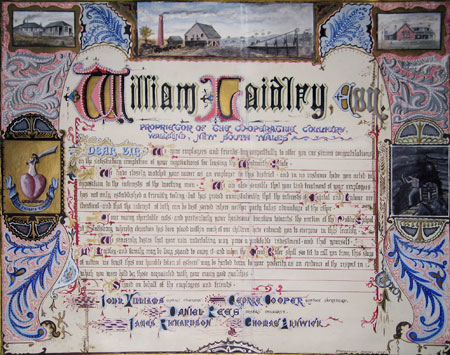

Colonial manuscripts were produced for welcomes and farewells, condolences and congratulations, retirements and for many other purposes. One 1892 address (which, like the Cliff album, was illuminated by John Sands) is an employees' testimonial to Messrs EMG Eddy, WM Fehan and CNJ Oliver, congratulating them on their exoneration of wrongdoing in the administration of New South Wales Government Railways.[30] Despite their diversity of purpose, a common language pervades these addresses. It is invariably couched in chivalrous tones, and words like 'gratitude', 'esteem', 'token', 'service' and 'respect' recur. Although the occasional nationalistic visual allusion appears, especially as the colonies moved towards Federation, chivalric sentiments and medieval iconography prevail in the colonial illuminated manuscript. Above all, each address was created as an inherently unique and sometimes consciously historical keepsake. In an address created by Lewis Steffanoni for William Laidley, his employees express a wish that the artefact be 'handed down to your posterity' (see Fig.1).

illuminated by C Relph

The album was presented to Cliff in leather-bound covers with a centred metallic crest of flourished initials 'JWC' (John William Cliff) on the front. Inside, the illuminations by John Sands Ltd exemplify the nineteenth-century revival of the art. The first page of the album contains the employees' address to Mr Cliff and, like each of the album's following 16 pages, it is profusely illuminated in beautiful and luminous tones of red, gold and blue. The album continues with a page of photographic portraits of Cliff and the company's two other partners, William Gardiner and Robert Vallack, followed by a page listing 63 employees, then 13 pages of their photographic portraits. Although individual names do not accompany the portraits (the names are listed on a separate page) they are clearly all male. If Gardiner and Co. employed any women, they are not mentioned or shown. The album's final section contains 34 albumen prints of grand Sydney buildings and views of New South Wales scenery, each identified in Gothic script with each page framed by a simpler illuminated decoration. Many of these photographs have been identified from the stock albums of photographer John Paine,[37] although the portraits may not be by Paine as he was one of the few colonial photographers who did not need to do studio portraiture to supplement his income.[38]

The Cliff album's introductory page featuring the employees' address (see Fig. 5) introduces the visual medieval allusion with a full foliate bar border having four mid-bar frame decorations.[39] The corner pieces feature the English rose (repeated once), the Scottish thistle and the Irish clover, a visual reference to the British Isles. The written address includes several flourished initial letters, while the main body of text is predominantly in Gothic script with language that typifies the chivalric tone. The miniature of a sailing ship painted on the bottom line is used as a 'filler' while also providing a visual link to the purpose of the address — the voyage of Cliff and his wife to Europe.

The first page of the 24-page section titled 'Photographs of New South Wales scenery' is framed by a foliated border of acanthus leaves, iconography that was extensively used in the medieval period, in predominantly red and blue colours, also typical of the medieval style.[40] The acanthus leaves emanate from a flourishing and lush cornucopia which symbolised the riches of the colony (Fig. 6). While some visual elements reflect the emerging Arts and Crafts style, itself an adaptation of the medieval form, the album's primary visual aesthetic is medieval.

The album's illuminator, John Sands Ltd,[41] and photographer John Paine, were outstanding practitioners of their crafts, and each were awarded prizes at the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition. John Sands Ltd was highly commended for 'Illumination', and Paine earned a first degree of merit for 'Photographs of Australian Scenery'. Writing on nineteenth-century Empire exhibitions, academic historian Peter Hoffenberg notes the importance of photography to the colonial exhibition movement, abroad and at home. He cites the request of JG Knight, a Victorian commissioner for the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition 'to focus on "principal business places and residences in the city and suburbs"'.[42] Paine's photographs gave the exhibition's commissioners what they sought: a demonstration to their international and domestic audience that colonial Sydney had matured as a centre of civilisation, commerce, and metropolitan power, modelled on the great British cities.[43] The Cliff album could serve Gardiner and Co. in a similar way, emphasising the company's status to prospective British clients.

Cultural heritage specialist Louise Douglas writes that the Great Exhibition inspired a flourish of exhibition activity in the Australian colonies. She notes the inherent contradiction in the visual rhetoric of exhibition displays: while colonial displays sought to showcase development and progress, they also needed to encourage potential immigrants and investors by revealing opportunities for exploration and exploitation.[44]

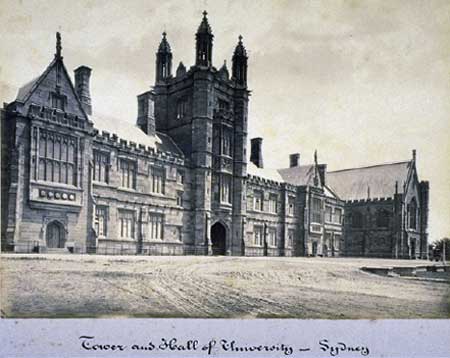

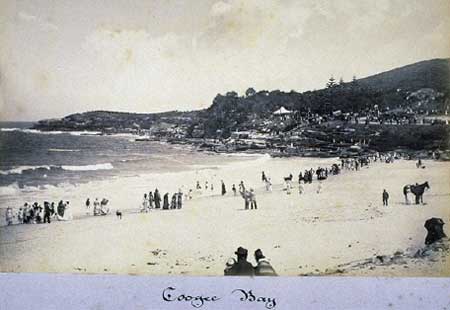

In this imperial and cultural milieu, colonial businessmen seeking orders from 'home' would have wished to allude to their traditional heritage, while demonstrating the progressive aspects of the colony. This is reflected in the aesthetics of the Cliff album. In a coalescence of neo-medieval artistry and the 'modern' medium of photography, images on the illuminated pages show the Exchange, the Commercial and New South Wales banks, as well as the commodious premises of Gardiner and Co. (Fig. 7). As at international exhibitions, the photographs connote impressive and appropriate repositories for all the capital, goods and labour that Great Britain could offer the colony, at a time when it depended on all three for economic growth.[47] The Town Hall, the General Post Office and the wide boulevards of George and Macquarie streets suggest metropolitan civilisation and order. St Andrew's Church of England cathedral, the Australian Museum and the University of Sydney represent edifices of religion, culture and learning, and in the case of the cathedral (see Fig. 8) and the university (see Fig. 9) replicate the Gothic-revival architectural style of Britain.[48] Seaside frolickers at Coogee Bay, clothed in respectable if inappropriate Victorian day wear, offer a scene of charming seaside activity (Fig. 10), while views of the Botanic Gardens present an aura of tranquil leisure. For the album's viewers, especially if they were being courted for business, the photographs provide assurance of the New South Wales colony's natural wealth and material progress, while the illuminations affirm its traditional heritage.

In exhibition photography, as Douglas reminds us, 'the virtues of the climate were romantically blended with seductive photographs of rural and urban locations'.[49] This is also present in the album. In the section containing 'photographic views of New South Wales' the images demonstrate the serenity of the Hawkesbury River and the beauty of Sydney Harbour, including Lavender Bay, where the Cliffs later resided in an impressive mansion. Other photographs reveal the spectacular wilderness of the Blue Mountains. However, the photograph of the 'Great Zig Zag' railway demonstrates to the entrepreneurial and adventurous nineteenth-century audience that the difficult topography of the 'wilderness' could be overcome by the ingenuity of colonial engineering. It also indicates that although the metropolitan centre is established, ample room remains for expansion. But in its utopian images of a built and natural environment that is virtually unpeopled, the album signifies by omission that there are no Aboriginal people to impede imperial progress, not even appearing as the exotic 'other'. Visual references and displays of Aboriginal people may have been thought a useful counterpoint to displays of colonial 'progress' in overseas exhibitions,[50] (and some images of Aboriginal people do appear in illuminated travel reminiscence albums),[51] but the imperatives of the colonialist context may have deemed their inclusion impolitic if the album was to be used to showcase the colony's potential and encourage investment in Gardiner and Co.'s import and warehouse business. Nor do scenes of lesser salubrity or social realism intrude on the select public image of Sydney's civic order and natural beauty.[52] The colony of New South Wales, the album's photographs proclaim, is itself an exemplary artefact of Empire and a testament to its 'civilising' influence. As such, it would have been a useful promotional and ideological tool for one of the importer's partners visiting England.

Beyond its simple documentary elements, what can the Cliff album reveal about colonial society? Certainly the act of presentation, a common late nineteenth-century practice, suggests a mutual respect and affection between management and worker. But an alternative reading can uncover other layers of meaning. For example, does such a gesture by the 'grateful employés' represent good labour relations, or was it designed to curry favour with management, and what was the source of their gratitude? In August 1882 the British Warehousemen and Drapers' Trade Journal noted in a reply to young men seeking advice on the likelihood of employment in the colonies for drapers' assistants, that in Melbourne and Sydney 'the drapers' shops are as complete and perfected a scale as respects details as any London West-end house' and over the past 25 years had 'got into a perfect business routine and stand very little in need of assistance from young men whose experience has been gained in the home trade'.[53] The employees may have been simply grateful to have their positions. In any event, was the album actually initiated by the employees or were Cliff's partners responsible? Did Cliff even take the album to Europe?

Although some of these questions cannot be answered with certainty we do know that Cliff, a senior representative of one of Sydney's prominent import and warehouse companies, was travelling to Europe on the crest of the economic boom of the late 1870s and early 1880s. Here was a handsome portfolio that not only asserted the commercial significance of Gardiner and Co., but also proclaimed the potential for investment in the colony. It would seem such outstanding promotional material would be included in the luggage of the wealthy Victorian sea voyager. As Gardiner and Co. had premises in Redcross Street, a prestigious warehouse street in London,[54] it would not likely be left behind. Importers and warehousemen were an essential element in the 'long boom'[55] and undoubtedly Cliff would have wanted to play his part in attracting British capital to his company.

John William Cliff seemed the epitome of the successful colonial immigrant and was clearly a man of adventurous, industrious and entrepreneurial spirit. In 1866, aged 22, he arrived in Sydney from Yorkshire, the heart of Britain's wool and drapery empire, where the possibilities of the drapery trade for an enterprising young man were apparent. On arrival he began working at Gardiner and Co.'s warehouse, established in 1856 and, by Cliff's time, one of Sydney's prominent drapery and soft goods warehouses. Gardiner and Co.'s warehouse was in George Street, described in a contemporary guidebook as 'a succession of lofty warehouses, rich in the produce of English and foreign looms and manufactories'.[56] Gardiner and Co. was conveniently located near the General Post Office, which provided vital information for Sydney importers via its Shipping Intelligence Board. By 1875 Cliff was a partner in Gardiner and Co. His timing was fortuitous, coinciding with a decade of exponential warehouse growth accelerated by Sydney's port growth from 1873 to 1883, especially the redevelopment of nearby Darling Harbour.[58]

The nineteenth-century warehouse was the forerunner of the modern department store, selling a diverse range of goods.[59] In his entertaining contemporary social commentary on the colonies Richard Twopeny observes that 'furniture, china and fancy goods have become the attributes of all the large drapery establishments'.[60] Gardiner and Co.'s eight-page advertising supplement in the Sydney Morning Herald's centenary edition of 1888 shows the 'Departments' of its new York and Clarence Street premises selling a plethora of goods that included haberdashery, clothing, dress goods, manchester, carpets, hessians, tarpaulins, leather bags and trunks.[61] Writing on the sociopolitical implications of the department store, author Gail Reekie says that warehouses and drapery establishments 'were outstanding examples of a monumental and masculine Victorian vision of public progress, wealth and enterprise'.[62] She also writes of an emergent 'culture of consumption'[63] in the late nineteenth century, where the masculine warehouse was a pivotal driver and the female shopper a compliant and necessary participant. Reekie shows that, from the 1880s, middle-class women began to emerge from the restrictions of the domestic cocoon into public spheres, undertaking charity work, essential and leisure shopping, and formal visiting.[64] She argues that 'the shopping woman's unpaid labour constituted the essential link between the home and the increasing range of manufactured foods, clothes, household tools and home furnishings which were coming onto the markets of western societies'.[65]

An array of these desirable consumer items was on offer in warehouses such as Gardiner and Co.'s, which retailed to the public, and a plethora of such goods was also present in the Cliffs' residence. When their Lavender Bay home was sold in 1891 the 76-page catalogue of their house contents featured 738 lots and reads like an inventory of luxury furnishings and artworks. The catalogue described Waiwera as 'so liberally endowed in the various departments of Art that it may be justly regarded as akin to a public gallery as well as one of the best Furniture-contained households in the Colony'. It proclaimed that the auction would be 'one of the most remarkable events that has yet happened in the auctioneering history of New South Wales'.[66] Even allowing for the auctioneer's hyperbole the catalogue reveals an impressive trove of domestic opulence with each room overflowing with valuable and fashionable objets d'art and paintings, reflecting the Victorian consumer culture of wealth, and where the domestic milieu sometimes emulated public museum display. If Cliff's wife, Jessie, conformed to the contemporary expectation of the wealthy woman's domestic role as homemaker, the auction catalogue indicates that she excelled at her work.

The extant records on Jessie Cliff are limited but, like her husband, she held her own season ticket to the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition[67] and, as the bearer of 16 children, she was an exemplary Victorian mother. Although the Cliffs relinquished many of their treasures in the auction, which may have been precipitated by Cliff's financial difficulties associated with personal business ventures, the 1882 illuminated album was not one of them. It was held in safekeeping for posterity and has become a rich resource on many aspects of British and colonial society in the nineteenth century.

Medieval illumination continued to be used in the manuscripts of the new century but the nineteenth-century ethos of chivalry from which it was derived could not be sustained through the First World War's incomprehensible horrors. An antiquarian and artistic interest in the medieval arts of calligraphy and illumination did survive beyond the war, but over the following decades medieval iconography began to fade from presentation documents as the artistic past gave way to the new and the modern. However, the illuminated manuscripts of the nineteenth century leave to posterity a rich artistic legacy. Colonial illuminated addresses can tell us much about medievalism and the colonial imperative, and reveal the ways in which Australian colonial society adopted a visual culture that conveyed British heritage and imperial ideology.

At first inspection the Cliff album provides the viewer with artistic and economic evidence beyond the antiquarian. Further consideration allows other issues to emerge: the link between warehousing and consumerism, the links between photography, colonial progress and the exhibition movement, along with facets of neo-medievalism in the colonial cultural and built environments. Each of these complemented the industrial and cultural imperatives of Empire. In addition, the illuminated album ideologically linked the new colony with the heritage and traditions of England.

In 1843 John Ruskin wrote: 'any material object which can give pleasure in the simple contemplation of its outward qualities without any direct and definite exertion of the intellect, I call in some way, or in some degree, beautiful'.[68] The Cliff album is indeed beautiful, and an antiquarian or cursory 'reading' of it offers some information on cultural, artistic, mercantile and economic practices. But if its wider context is not considered, a much richer meaning remains hidden. Although the intriguing questions of the illuminated album's origin and purpose cannot be answered with certainty at this stage, a wider historical interpretation reveals many more layers relevant to its cultural, social and economic significance. They are as absorbing and as colourfully infused as its beautiful pages.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed.

1Cliff Collection, Macquarie University Australian History Museum. I am indebted to the late Mr Clarence Cliff, the late Mr John Harris and late Mrs Lynne Harris, Dr Lynne Outhred, Mrs Hilda Wakelin, Mrs Margery Connelly and many members and friends of the Harris family for their assistance and encouragement during my research for this article. I am also indebted to the Modern History Department and the Australian History Museum at Macquarie University for support and assistance and to Dr Marnie Hughes Warrington for guidance.

2For example: Wendy Prior, 'Illuminating Oakleigh', La Trobe Library Journal, vol. 11, no. 42, spring 1988, 37–41.

3Mark Girouard, The Return to Camelot: Chivalry and the English Gentleman, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1981, p. 221.

4Sarah Randles, 'Rebuilding the Middle Ages: Medievalism in Australian architecture', in Stephanie Trigg (ed.), Medievalism and the Gothic in Australian Culture, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2006, p. 168.

5Trigg (ed.), Medievalism.

6Randles, 'Rebuilding the Middle Ages', p. 148.

7Girouard, The Return to Camelot.

8ibid., p. 22.

9George III, The Royal Collection e-Gallery, www.royalcollection.org.uk/eGallery/collector.asp?collector=12761

10SC Hall (ed.), The Book of British Ballads, Jeremiah How, London, 1842.

11Girouard, The Return to Camelot, pp. 107–8.

12ibid., p. 148.

13Christopher Menz, Morris and Co, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2002, p. 20.

14For examples of his style see: www.morrissociety.org/graphics/horace.gif )

15Girouard, The Return to Camelot, p. 93.

16ibid., p. 88.

17ibid., p. 148.

18Peter Proudfoot, 'The international exhibition phenomenon — Sydney on show to the world', in P Proudfoot, R Maguire & R Freestone (eds), Colonial City Global City, Sydney's International Exhibition 1879, Crossing Press, Darlinghurst, 2000, p. xv.

19Girouard, The Return to Camelot, p. 228.

21Christopher De Hamel, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts, Phaidon Press Limited, Oxford, 1986, p. 159.

22For some examples from the medieval period see online image gallery for The Medieval Imagination: Illuminated manuscripts from Cambridge, Australia and New Zealand, www.slv.gov.au/programs/exhibitions.

23WR Tymms & MD Wyatt, The Art of Illuminating, facsimile, Wordsworth Editions, 1987, p. 52.

24Dinah Birch, 'Introduction', in Dinah Birch (ed.), Ruskin and the Dawn of the Modern, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p. 1.

25Birch, 'Introduction', p. 4.

26Jose Harris, 'Ruskin and social reform', in Birch, Ruskin and the Dawn of the Modern, p. 13.

27John Ruskin, Lectures on Art Delivered Before the University of Oxford in Hilary Term, 1870, George Allen, London, 1900, p. 117.

28Victoria Emery, 'The daughters of the court: Women's medievalism in nineteenth-century Melbourne', in Trigg, Medievalism, p. 179.

29Girouard, The Return to Camelot, p. 222.

30An image of this address can be seen at http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an5601619.

31See 'The Arts and Crafts Movement in Australia', on the Australian Government Culture Portal, http://cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/artsandcrafts/.

32See entry on Edward Myers, Dictionary of Australian Artists Online, www.daao.org.au/main/read/4642.

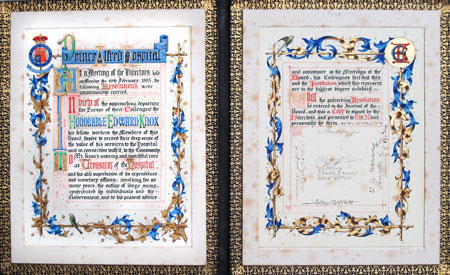

33See the State Library of New South Wales catalogue entry for the Edward Knox illuminated address, ttp://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/item/itemDetailPaged.aspx?itemID=431370.)

34Daniel Thomas, 'Bateman, Edward La Trobe (1815?–1897)', Australian Dictionary of Biography — Online Edition, http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030110b.htm.

35Stephanie Burley, 'Adams, Sophia Charlotte Louisa (1832–1891), Australian Dictionary of Biography — Online Edition, http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/AS10006b.htm?hilite=sophia%3Badams; Mary Kneipp, 'Rowland, Caroline Ann (1852–1921), Australian Dictionary of Biography — Online Edition, http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A110476b.htm?hilite=caroline%3Browland; Brian Andrews, 'Mary Emma Ullathorne', Dictionary of Australian Artists Online, www.daao.org.au/main/read/6316.

36Peter Beal, A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology 1450–2000, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008, p. 192.

37I am indebted to the late Catherine Snowden and Dr Peter Stanbury for this information. Photographs identical to some of those included in the album are attributed to Paine in the National Library of Australia Digital Collection at PIC P2116/1-29 LOC Album 104. See also photographs Number 8, 9, and 19 in Sun Pictures of New South Wales; part 2 [1880] album of photographs by John Paine, Mitchell Library, PXA 1119. See also Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, John Paine Collection MM: HP82.39.039, 746, 767, 771, 773.

38Alan Davies & Peter Stanbury, The Mechanical Eye in Australia — Photography 1841–1900, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, p. 64.

39For an explanation of terms see Michelle P Brown, Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms, JP Getty Museum in association with the British Museum, Malibu, 1994, p. 125; see also Beal, Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology.

41The album's illuminator is given as 'John Sands', but as he died in 1873 it is likely to have been an employee.

42Peter Hoffenberg, An Empire on Display — English, Indian and Australian Exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War, University of California Press, London, 2001, p. 141.

43Catherine Snowden, Alison & Christa Ludlow, John Paine Landscape Photographs c1880, Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, 1984, p. 6.

44Louise Douglas, 'Representing colonial Australia at British, American and European international exhibitions', reCollections, Journal of the National Museum of Australia, vol. 3, no. 1, March 2008, http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_3_ no_1/.

45Proudfoot, 'The international exhibition phenomenon', p. xvi.

46Louise D'Arcens, '"The last thing one might expect": The Medieval Court at the 1866 Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition', La Trobe Journal, no. 81, Autumn 2008, 1–11.

47Michael Daly, Sydney Boom, Sydney Bust: The City and its Property Market 1850–1981, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1982, p. 138.

48Randles, 'Rebuilding the Middle Ages', p. 149.

49Douglas, 'Representing colonial Australia', p. 9.

50ibid., p. 11.

51'Album of photographs of a voyage to Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney in 1878 by Frederick Green in S. S. Aconcagua', National Library of Australia, PIC NK4055 LOC Album 24.

52Snowden et al., John Paine Landscape Photographs, p. 8.

53 Warehousemen and Drapers' Trade Journal, 19 August 1882.

54 Post Office London Directory, 1881. The building was destroyed during Second World War German bombing raids.

55See Peter Proudfoot, 'Wharves and warehousing in Central Sydney 1790–1890', Great Circle, vol. 5. no. 2, October 1983, 73–86.

56Gibbs, Shallard & Co., An Illustrated Guide of Sydney 1882, facsimile edition, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1981, p. 26.

57 The Storekeeper, 16 November 1896, p. 15.

58Proudfoot, 'Wharves and warehousing' (p. 78).

59Kimberley Webber, '"The great civilizer": The sewing machine in Australia', Museums Australia Journal, vols 2–3, 1991–92, 169–94 (p. 176).

60REN Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, London, 1883, p. 199.

61 Illustrated Sydney News Centennial Number, supplement, 26 January 1888.

62Gail Reekie, Temptations — Sex, Selling and the Department Store, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993, p. 4.

63Gail Reekie, 'Women and work: Manufacturing gender in retailing and the clothing trade', in R Mile & B York (eds), Workers and Intellectuals: Essays on Twentieth Century Australia by Ten Urban Hunters and Gatherers, Edward Blackwood, London, 1994, p. 8.

64ibid., p. 7.

65Reekie, Temptations, p. 7.

66 Newton & Lamb Auctioneers, Cliff Collection, Australian History Museum, Macquarie University.

67See Cliff Collection, Australian History Museum, Macquarie University.

68Cited in Nicholas Shrimpton, 'Ruskin and the aesthetes', in D Birch (ed.), Ruskin and the Dawn of the Modern, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p. 133.