Cinema India: The art of Bollywood

review by Rochona Majumdar

The success of the latest Shah Rukh Khan blockbuster Chak De India (dir. Shimit Amin, 2007) once again raises for cultural theorists, film buffs, sociologists and anthropologists interesting questions about the global presence and reach of Bollywood. Key to Bollywood's globalisation has been the proliferation of films whose storylines are based in countries outside India, extensive foreign shootings, and finally the showing of Hindi films in mainstream theatres in urban centres in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Chak De India's climax — where the formerly disgraced hockey coach, played by Khan, leads his team of female players to victory at the World Hockey Championships — was shot in Sydney, a testimony to the popularity of Australian locales in the Hindi film industry. If this fact speaks to the close links between Hindi film production and the tourism industry in Australia, the recent exhibition 'Cinema India: The Art of Bollywood' in Sydney's Powerhouse museum highlights the ways in which the aesthetic of Hindi cinema has found a small but not insignificant place in the Australian multicultural public sphere.

Spectacular posters line the walls of

Cinema India

The Powerhouse exhibition draws largely from the exhibits that were first displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London and subsequently at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in Melbourne. But as the primary exhibition travelled from London to Australia, the museums have added crucial creative components that address the question of Bollywood's presence in Australia. When the exhibition first opened in Melbourne, it included an extremely interesting section on 'Fearless Nadia', Bombay cinema's first and only stunt queen. Few would have known that Nadia was originally Mary Evans, a Perth-born Greek woman who travelled to India with her family. She reigned supreme on Indian screens, performing intrepid stunts, punishing wicked wrongdoers, rewarding the good and upholding women's rights in a patriarchal society, all through the 1930s and early 1940s. The Powerhouse display also includes the Nadia section, mainly in the form of clips taken from a series of rare Hindi films (like

Diamond Queen and

Jungle Princess) featuring the actress. But the Powerhouse has also enriched the V&A and NGV exhibits by adding a section that is much more directly about Bollywood in/and Australia.

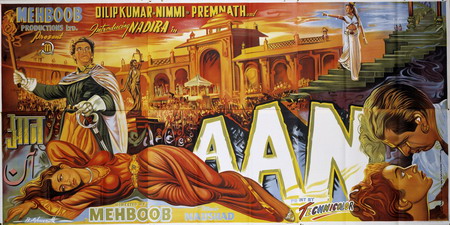

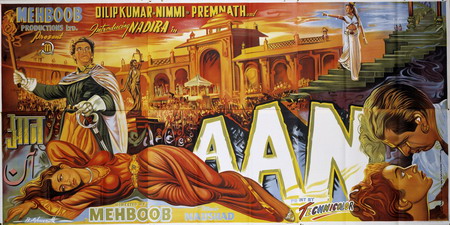

Poster,

Aan

(Savage Princess), 1980s

designed by Bide Viswanathan

© V&A Images/courtesy Mehboob Productions Private Ltd

In this section we see a series of posters from more recent Hindi films whose plots were wholly or partly based in Australia (

Salaam Namaste,

Dil Chahta Hai,

Chak De India,

Heyy Baby), a small section on the costumes worn by Preity Zinta and Tania Zaetta in

Salaam Namaste, as well as an interactive/pedagogical section on Bollywood song and dance sequences intended to both familiarise spectators with this crucial feature of Hindi films and also to encourage them to participate in this new cultural form. The Powerhouse, in the early days of the exhibition, sponsored a series of events where large numbers of spectators participated in these song and dance routines.

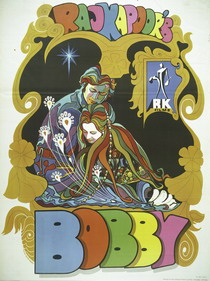

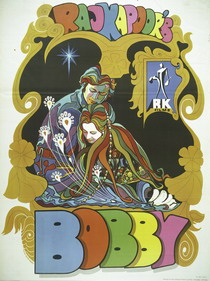

Poster,

Bobby, 1973

designed by Tilak, Tirath & Oberai

© V&A Images/courtesy RK Films

The Powerhouse exhibition is set up to capture what curator Rebecca Bower describes as an actual Hindi movie-going experience. Audiences step into the portals of the exhibit walking past some costumes from Baz Luhrmann's

Moulin Rouge (2001), a film that revived the musical in Hollywood and was the director's homage to the inspiration he got from the styles of Bollywood. Walking on the red carpet with song tracks from Hindi films playing in the background induces a retro feel that is deepened as we look at the rich display of Hindi cinema poster art from the 1940s to the present day. The posters are divided thematically into seven sections namely: 'The glory of India', India after independence', 'Depiction of women, love and romance, 'Youth and internationalism', '1970s and 1980s' and 'Global perspective'. Within these large themes of the posters however are a number of sub themes — the tussle between family honour and romantic love, the conflict between the rural countryside and the new urban metropolis, the rise of teenage love, female sexuality and the courtesan — that have dominated Hindi cinema. For example, the posters of

Anarkali (1953) and

Aan (1952) draw attention to the themes of love and honour, as well as to the conditions of post-independence India (

Aan) and India's pre-colonial Mughal history. Similarly, the poster of

Shree 420 (1955) demonstrates the impact of the Charlie Chaplin-inspired tramp image on India's own citizen hero Raj Kapoor. The posters depict Bollywood cinema's commitment to themes of social melodrama and mass entertainment. They also demonstrate with a clarity otherwise not grasped by the lay viewer that Bollywood cinema is its own richest archive. Thus the poster of the teenage romance

Bobby clearly traces its lineage to romantic Hindi films of the 1950s romances such as

Barsaat. Likewise it highlights the increasing acceptance of a 'Western' consumer culture among the urban Indian middle class first depicted in films such as

Jewel Thief. The posters of films from the 1990s, including

Dil To Pagal Hai,

Lagaan and

Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, celebrate India's embrace of global cosmopolitanism, while those like

Dhoom 1 and

2, and

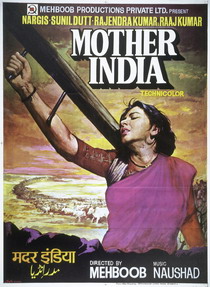

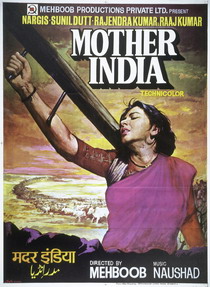

K3G depict the widespread acceptance of capitalist consumerism in India's newly liberalised economy. The posters are also an excellent testimony to the history of modern Indian art — the influence of art deco in the 1930s, graphics from the 1960s and 1970s to modern digital technology in the new millennium. Finally, the posters tell the story of women's empowerment in India. This is most clear as we contrast the images of Nargis as virtuous

Mother India in the film poster of Mehboob Khan's blockbuster of that name from the 1950s with the beautiful nineteenth-century courtesan of Umrao Jaan Ada played by Rekha in the 1980s film

Umrao Jaan, remade once again with Aishwarya Rai in 2006. These images of womanly virtue, purity and chastity stand in marked contrast with the bold, self-reliant, and confident images of women depicted in posters from the 1990s in films such as

Salaam Namaste and

Fire.

Poster,

Mother India, 1980s

Seth Studios

© V&A Images/courtesy Mehboob Productions Private Ltd

The Powerhouse exhibit includes a couple of items which are of interest in and of themselves but have unfortunately not been contextualised adequately. These include 'Jadoo', the animatronic head used in the sci-fi film

Koi Mil Gaya, India's version of ET, and the gorgeous costume worn by Aishwarya Rai in the Yash Yaj hit

Bunty aur Bubli during the song sequence 'Kajra Re'. It would have been instructive for spectators to have been exposed to a little more information about the evolution of science fiction as a genre in Indian films or to some observations about the changing notions of what constitutes beauty in the female form in India. The latter is especially interesting as the exhibition also includes posters from

Gajagamini (2000), a film inspired by India's leading painter MF Hussain's ideas about female beauty. Lack of space has led to a paucity of detail in some of the Powerhouse's exhibits. In the 'Fearless Nadia' section, for example, some more biographical detail on this extraordinary figure would have told audiences about a film history that few are aware of today. How did a woman who looked so obviously 'Western' succeed in Indian films? What were the filmic influences that led Wadia Movietone to produce so many stunt films featuring Nadia? What did it mean for a woman to be performing such stunts on screen when the reality of women's lives in the 1930s and 1940s was often a story of deprivation, confinement and discrimination? It would also interest many to see some reflections on the figure of the 'white woman' in Bollywood cinema, starting with Nadia in the 1930s, up to

Lagaan and

Rang de Basanti in the twenty-first century.

Poster,

Circus Queen, 1959

private collection, Mumbai, India

© Wadia Movietone (Private) Ltd

But these minor quibbles aside, the small but finely textured exhibition at the Powerhouse is a wonderful introduction for Australian museum-goers to the art(s) of Bollywood — poster art, couture, sets, fight sequences and music.

Rochona Majumdar is an assistant professor in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago.

|

Institution:

|

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, with Australian components developed by National Gallery Victoria and the Powerhouse Museum

|

|

Curatorial team:

|

Rebecca Bower and Christina Sumner

|

|

Design:

|

Beth Steven

|

|

Venue/dates:

|

National Gallery of Victoria, 9 March – 20 May 2007

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, 6 June – 11 November 2007

|

|

Publication:

|

Cinema India: The Art of Bollywood, by Divia Patel, Laurie Benson and Carol Cains, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2007. RRP: A$29.95

|

|